Day 3 of HippFest at Home sees us journey to the (faux) Scottish coast for a (faux) Scottish drama starring Mary Pickford. This programme of a short and feature was given introductions by Alison Strauss (once more) and Pamela Hutchinson (who of course runs the marvellous Silent London). Strauss explained the choice of films, focusing in particular on the short extract from an amateur film shot on location in Harris in the Outer Hebrides. She also highlighted HippFest’s pioneering efforts to provide audio-description via headphones and brail for these films. It’s a superb project, and another reason to admire the festival. Hutchinson gave a detailed introduction to The Pride of the Clan, highlighting its history in the context of Pickford’s career. (I will say a little more about the film’s critical reputation, which Hutchinson also covered, later.) As ever, these introductions were exceedingly engaging (and often very funny). As an online viewer (and viewing the film over a day later), I felt part of the crowd in situ. On this theme, there was a lovely moment when the Bo’ness audience cheered the restoration team of The Pride of the Clan, who were (like me) watching remotely from their respective homes. Polly Goodwin, who provided the audio descriptions, was also warmly cheered. You really get the feeling of the enthusiasm for everyone involved. I’m sure it’s the same at any such specialized festival, but HippFest is the only one I have experienced where the online version gives you such access to the people and atmosphere responsible for making it work. And so, to the films…

Holidaying in Harris (1938; UK; Nat and Nettie McGavin). A fragment of a longer document, this is (like yesterday’s shorts from Ireland) another amateur glimpse of real life. Here are the docks, the fishing boats, the baskets of herring, the men on deck, the women at work on the shore. The camera observes, unobtrusively. The past goes about its business – messy, sweaty, industrious. The film ends. While this little extract doesn’t have the chance to sustain its mood, it’s a potent window into a way of life long gone – and the faces (and, especially, the hands) of those who often go unrecorded in history. A lovely little treat to start things off.

The Pride of the Clan (1917; US; Maurice Tourneur), our main feature. Set on the remote Scottish island of Killean, the film follows Marget (Mary Pickford) who must lead the MacTavish clan after the death of her father at sea. She wishes to marry Jamie Campbell (Matt Moore), but Jamie’s real parents – a wealthy countess and earl – arrive and convince her that it’s best for his future to let him join leave the clan. She accedes to their wishes but decides to sail away herself. However, her old boat soon begins to take on water. Will the hero rescue her in time? (I’ll let you guess.)

Let’s start with the good. Though it was shot in Massachusetts and thus has no visible connection with the reality of the Scottish landscape, the film at least boasts a wealth of exterior photography. There are some marvellous scenes of the locals silhouetted on the cliffs or gathered on the coast. The director Maurice Tourneur shows a keen eye for composition, making the most of the (actually quite limited) location spaces. There are some efforts to make this landscape bear some sense of history, though I must say that the church, neolithic tomb, and standing stones look hopelessly unconvincing next to some of the (clearly real) houses in the village.

Pickford is the heart of the film, and its chief asset. She’s feisty, independent and gets to be both playful and boisterous – telling stories, commanding children and adults, quite literally wielding a whip. I just wish the film did more with this tomboyishness. She might well wield a whip, but she ends the film clutching her pets as the water rises and the hero races to the rescue. Turning her from heroine to helpless waif is something of a letdown, as is the dramatic implication that by seeking an independent identity elsewhere she must inevitably come a cropper. (I rolled my eyes, too, at the intercutting of the villagers’ prayers – especially the unbelieving Gavin – with the rescue.)

Marget’s romance with Jamie is a little awkward, with the couple having little discernible chemistry (at least, nothing that I would call “romantic”; the very idea of sex, of course, is utterly absent). The humour plays well enough, but the film is far too chaste to express or even suggest anything deeper. (An early embrace ends with the pair awkwardly leaning into each other, cheek to cheek, that is surely as uncomfortable for the lovers as it is unconvincing for us as viewers.) Much of the film allows Pickford to be playful with the clan children and animals, making faces, pulling japes, or bothering kittens and donkeys, which certainly helps raise a smile but also risks infantilizing her character to the extent that the whole point of her being the head of the clan seems nothing more than a game. Besides, the whole effort of the film to present us with anything resembling real life in a real location seems to me a failure. The film might have nice images of the sea and coast, but the life of the clan seems to involve being either pious, playful, or bashful. There is little work here, and if there is a risk of death at sea, there is little dirt and no disease on land. While I appreciate that the colloquial dialogue is being used to ground the film in a sense of location, it swiftly grated on me – grated because the effort to capture the local dialect stood in stark contrast to the absence of any reality elsewhere.

Ultimately, The Pride of the Clan is all a fantasy – which is fine, but it never grabbed me. It is no more convincing or moving than the story Marget tells Jamie, visualized in absurd cutaways to a life on an exotic island complete with native cannibals. What works best are the moments of calm in-between the wearying playfulness. There is a scene of Marget alone, tying a bouquet which she drops into the sea – a gesture one might find in a D.W. Griffith film, only here carrying less emotional weight. It’s a glimpse of what might have been. For much of the film, I felt rather like Gavin, the outsider who scowls on the rocks while the loyal clansmen attend church and have faith in the narratives told therein.

This brings us back to the film’s reputation. As I mentioned, Hutchinson spoke about this film’s supposedly poor critical reception in the US in 1917 – and Pickford’s own subsequent dismissal of The Pride of the Clan as a failure. Hutchinson spoke extremely engagingly about the film’s qualities, and in the programme notes available online by Thomas A. Walsh and Catherine A. Surowiec there are other voices of praise. But these positive notes come chiefly from material that these respective authors quote. (Perhaps they are, wisely, a little cautious about making too great a claim for this film.)

Of particular note in the Walsh/Surowiec piece is a citation from Richard Koszarski, writing in 1969, who said: “Tourneur’s eye for composition is flawless, equalling or surpassing Griffith’s work of the same period, and the performances are more restrained than in much of Intolerance. Clearly this film was ten years ahead of its time.” Hmm. Ten years ahead of its time? I can imagine such a slender narrative being handled by Griffith in, say, 1911 in about twenty shots with twenty times the emotional power. (Equally, I can imagine him padding out such a narrative in, say, 1923 in about two thousand shots and achieving less.) Think of Mary Pickford in Ramona, from 1911, a Biograph production that boasts subtle performances and a masterful use of composition and choreography. (I have written about the film and its (to my mind) inferior re-adaptation as a feature film in 1928.)

Something I kept noticing with Tourneur’s film is the gulf between interiors and exteriors, which is only rarely bridged. One thinks of Victor Sjöström’s Terje Vigen (also released in 1917) as another coastal film featuring grief, wrecks, and the life of fishermen. Despite sharing tropes, the two films are worlds apart. The Swedish film builds partial sets on the coast so that we can look through windows and doors from interior to exterior, from comfy interior to raging sea. The result is an astonishing sense of place and of emotional tone: Sjöström’s film is anchored in reality, a fact which the naturalistic performances redouble. The only image in which this is regularly achieved in The Pride of the Clan is of Marget silhouetted in the doorway of her boat (an image that features in a repeated intertitle design). While The Pride of the Clan shows many characters looking in/out of windows, there is no attempt to link the spaces – aside from Marget’s boat, I cannot recall any shots where we look from interior spaces to the sea. And while many images are very nicely composed, only one image really sticks with me: the stunning silhouette of Marget and Jamie against the moonlit sea. It’s beautiful in and of itself, but also as a distillation of feeling. There weren’t enough moments like this. I wish that there the drama had been less fleetingly embedded in the setting and photography.

The issue is not helped by the variable image quality. From the restoration credits, it is clear that The Pride of the Clan was restored from a mix of 16mm and 35mm copies. While the 35mm sections are superb, these unfortunately make the 16mm sections seem all the more dulled. But would sharper images help this film? For me, I fear not. I found the whole thing cumulatively underwhelming.

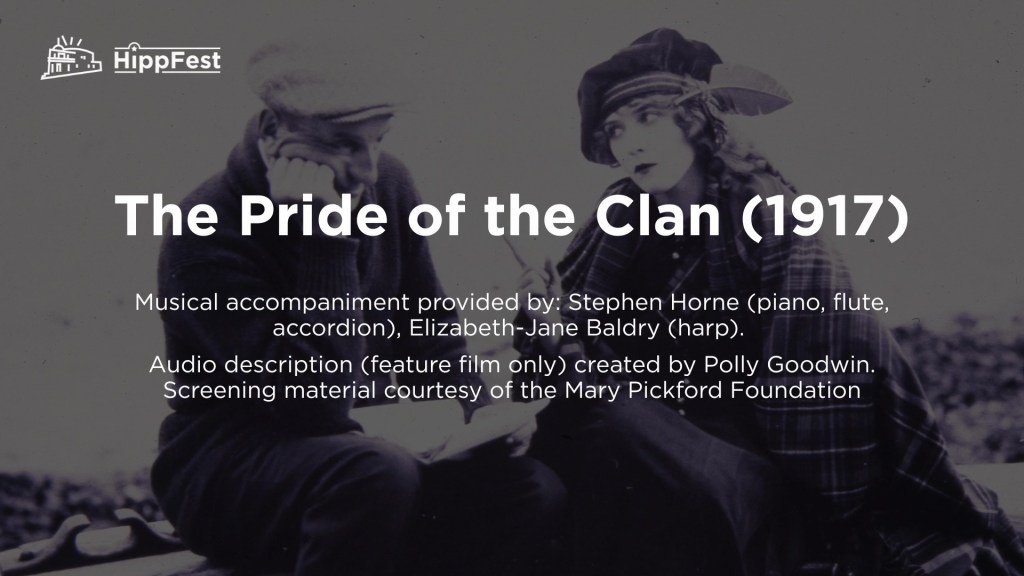

Well, that was Day 3. Goodness me, I wish that I enjoyed The Pride of the Clan more than I did. But I certainly enjoyed the music for this screening, provided by Stephen Horne (piano, flute, accordion) and Elizabeth-Jane Baudry (harp). This pair always produce gorgeous sounds, and in this case I found the music often more evocative than the film itself. Since the sound is recorded live for the videos available through HippFest at Home, you can also hear the Bo’ness audience reacting to the film – which (in this context) I very much enjoyed. If the film failed to charm me, the event itself was certainly charming.

So that was my last day of HippFest at Home. I should explain that there is a fourth online programme on offer: “Neil Brand: Key Notes”, a talk with music and film extracts. As much as I admire Brand’s work, I feel that this kind of event is not aimed at me. Aside from reasons of my own schedule, another reason that I feel able to skip this presentation is that HippFest at Home offers single tickets for individual screenings, rather than an all-in price for any/all events online (like Pordenone). I can see the benefit in this, as I have sometimes found that festivals replicate each other’s material (even online), or else include something that for whatever reason I don’t wish to see, and I regret not experiencing everything on offer.

Finally, I must repeat what I have said on all three days: HippFest at Home is simply the best presentation of an online festival that I have experienced. Everything about it, from the website, the programme notes, the video options, the introductions, the music, and the sheer enthusiasm of everyone involved, made me feel incredibly welcome. I have often written about the inevitable feeling of dislocation when “attending” online festivals. While HippFest at Home does not offer its online audience the same number of films as Bonn (ten features in 2024) or Pordenone (eight features plus several shorts in 2024), their presentation impressed me more. More of the live element was included in the online videos, and I loved being able to see the speakers and musicians – and the audience. I’m incredibly impressed by the effort of all those involved, and if any of them are reading this then I offer them my warmest congratulations. I’m sad that it’s taken me this long to attend HippFest in any guise, and I will certainly be revisiting – in one form or another – next year.

Paul Cuff