The first part of Day 2 is devoted to Norma Talmadge, with a short from 1912 and a feature from 1920.

Mrs. ‘Enry’ Awkins (1912; US; Van Dyke Brooke)

Norma Talmadge is surrounded by a motley collection of men: her father (a gout-ridden drunk), her father’s friend Bill (a rough who’s happy to punch down), her lover Henry (not without charm, but his arm-in-a-sling suggests not the strongest), her father’s doctor (who manages to reconcile father and daughter, even if he can’t stop the father drinking). It’s Talmadge who dominates every scene she’s in: force-feeding her father, slapping Bill, dominating Henry. The film offers a series of snapshots into a working-class life, fast-forwarding through an unspecified period of time. Is it days? Weeks? Liza is at home, on the street, at home, at a theatre; she is making Henry jealous, she is marrying him; she feeds her father, she is estranged from her father, she is reconciled with her father. There are several suggestions that we are in London: the policeman’s uniform, the selection of street views, the fashion. When I say fashion, I mean trousers: Bill’s dog-tooth pair that he wears to take Liza to a variety show, Henry’s pair with a double row of buttons that he wears for his wedding to Liza. (There are more buttons on his cap; a budget pearly king). It’s a curiosity. A few pages from a Victorian novel, whole chapters missing, with glimpses of a life imagined. Talmadge’s eyes are more intelligent than the film from which she stares out.

Yes or No (1920; US; R. William Neill)

Norma Talmadge plays two roles: Margaret Vane, a rich society woman with a husband suffering from overwork and a heart condition; Minnie Berry, a poor working-class woman whose husband, Jack, works too hard (for Mr Vane) to spend time with his wife. Both women are pursued by ne’er-do-wells: the lounge lizard Paul Derreck woos Mrs Vane, the dodgy lodger Ted Leach woos Minnie. Which wife will say “Yes” to their wooer, and which “No”?

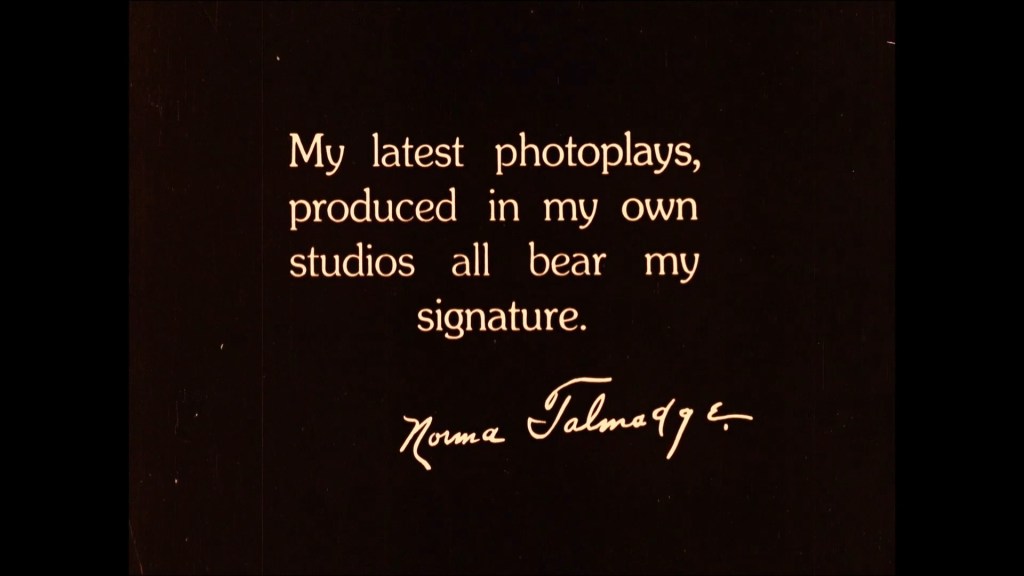

The film’s opening titles are revealing: they wear their moral message on their sleeve, they are aesthetically dubious, and they foreground the status of Norma Talmadge. It’s a mark of her prestige that the most significant title of the credits is her own boast of personal quality control. She signs the title with the signature signature-style of a D.W. Griffith or Cecil B. DeMille. It’s a nice reminder that there were powerful women in Hollywood who could hold their own against the big male names of the industry. Of course, the film is also “presented by” Joseph M. Schenck, Talmadge’s husband. The family feel is completed by the fact that Minnie’s sister Emma (who is also Margaret’s maid) is played by Natalie Talmadge, the sister of Norma Talmadge. (And yes, to extend the family machinations, the sometime wife of Buster Keaton, Schenck’s employee.)

Margaret has a luxurious home, filled with everything soft, luxurious, and fluffy one can imagine. This includes a ludicrous little dog, a kind of animate powder puff. (Silent it may be on screen, but you can sense how irritating is its bark.) In her world, even the flower her admirer gives her is luxurious: not just a single flower, but a huge sprig, almost as tall as Margaret.

It’s almost a relief to go into Minnie’s home. Almost, because it is crammed, albeit with life. Children scamper messily, dinner is always on the boil, washing always needing doing. Talmadge lets Minnie be more expressive, more open, more sympathetic, than Margaret. Makeup and hair ally us with Minnie. As Margaret, Talmadge sports a blonde wig that looks faintly intimidating; one cannot imagine stroking her hair. Minnie’s hair is Talmadge’s own; it is pulled back naturally, a little untidily, practically; one longs for her husband to reach out and show her some tenderness.

Yes, Talmadge allows herself more room for expression with Minnie—but it’s so deft, so subtle, so telling. She finds a book for her husband, gives it to him; she smiles at his closeness, and when he leaves without a kiss or a touch, she holds her pose while letting her face and body give a kind of sigh, of tiredness, of sadness. When she thinks, we see her think, and sometimes her glance brushes past the camera as her eyes move across the scene. You want to offer her a smile, to tell her it’ll be alright in the end. Goodness, yes, Talmadge is magnificent: the way she looks when no-one but us can see her. Minnie’s husband leaves for the evening and her face falls; he comes back to kiss her, and her face lights up. When the lodger touches her arm after giving her a gift, she is alone and feels her arm where he touched her: as if remembering what physical intimacy was, or might be—and whose intimacy she wants.

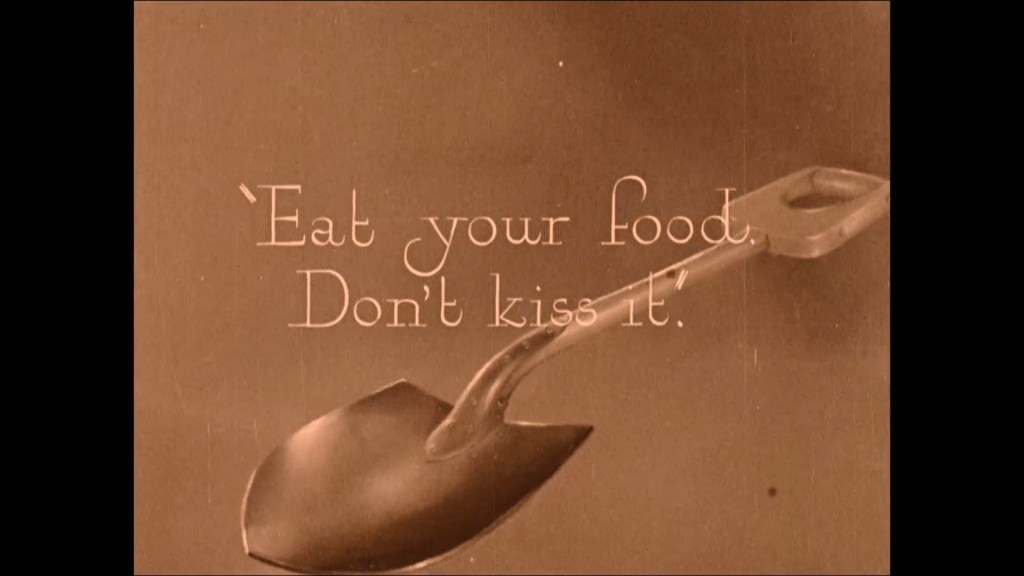

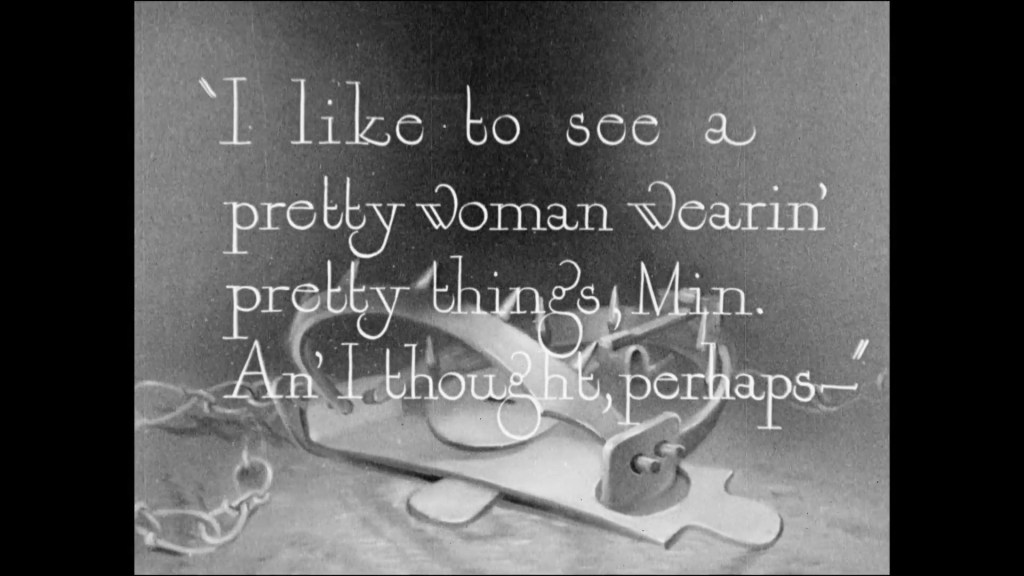

But for all these magical little moments, the film is a frustrating watch. Frustrating, because the film plays out exactly according to its set-up (and allegorical names) suggest. Frustrating, because Talmadge’s subtlety is surrounded by clumsiness. I’m thinking principally of the intertitles, most of which have text superimposed over crass painted designs.

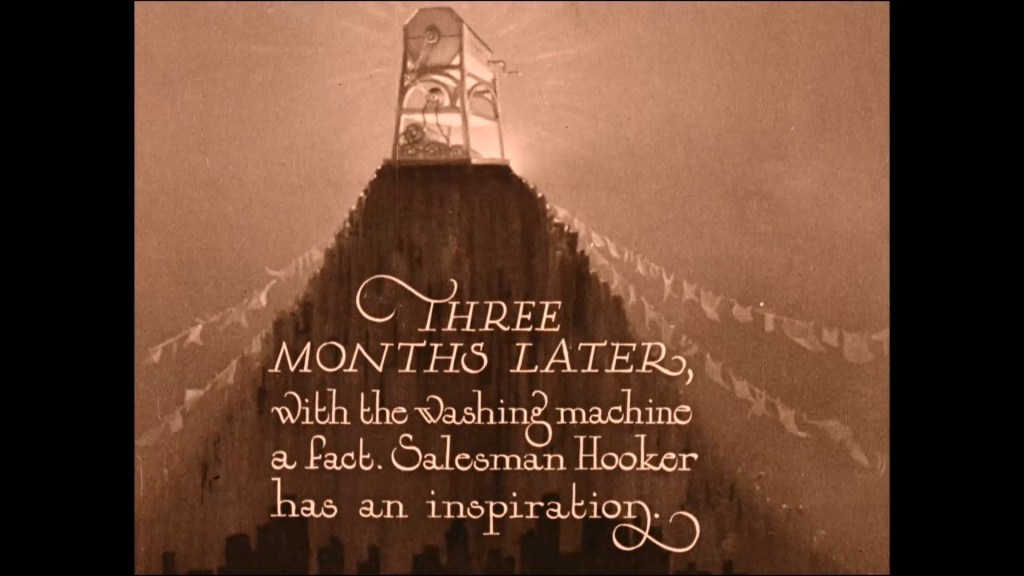

If I had no text of my own and simply shared the film’s titles with you, these background images would tell the whole film: I can’t think of a film which so earnestly spells out everything in this same way.

Mr Vane’s doctor is introduced with a doctor’s bag under his name. Fine. But do we need to see a knife and fork on a table under the title announcing that dinner’s ready? Or a movie ticket in a title saying they’re off to the movies? Minnie’s brother, Tom, speaks his mind, but is he so bolshy that he needs a lit bomb under his words criticizing their boss?

The ne’er-do-well characters have it worse. It isn’t enough that Paul Derreck wears a sinister smoking jacket or kisses Margaret’s hand in a way that makes your flesh creep. No, his words are imposed over images of mantraps, chains, or—and here my mouth literally fell open with disbelief—an image of Satan lurking in the shadows. Really? Yes, really.

And Minnie’s husband doesn’t get off the hook, either. His dreams of designing a washing machine give rise to fabulous visions of their golden future. The film doesn’t show us a pie in the sky, but it might as well: a washing machine on a mountain, blazing bright over the metropolis. Mythical domes dreaming in soft clouds. I can do without this sort of thing, thanks.

The film, too, eventually (to paraphrase a contemporary author) puts down the needle of insinuation and picks up the club of statement. When things get serious and Jack rescues Minnie from the (by now) openly sexually aggressive Leach, it’s fists to the rescue: Leach is pummelled, then unceremoniously dumped down a staircase, and the film isn’t even interested to know if he’s crippled for life. Meanwhile, Margaret leaves her husband for Paul, which is the final blow to the husband’s heart. He dies, and Paul is revealed “not to find the widow as attractive as the wife”. After threatening to kill Paul if he doesn’t marry her, the pair fight and Margaret is left in her false paradise of a home. Emma is still there, still sympathetic. But she too takes her leave. There is a ghost of a kiss between widow and maid. It’s the only sincere kiss in Margaret’s story, and it’s barely made. (A different film and a different director might have made this moment more loaded.) The kiss is gone, the maid leaves, Margaret picks up a gun. Fade to black. Title: “The world soon forgot the death of Margaret Vane.” For once, the words of the title do the talking: it’s a blunt, sad, brutal transition.

And what a relief that the title designs fall away for some of the most intimate moments of dialogue at the end of the film. Their absence is part of why the final scene is so delicate, so uneasy. The Berry couple live in a new apartment, well-furnished (but not excessively so, like the Vanes’). The children are happy, playing with their uncle Tom. And the married couple? “There wouldn’t be much unhappiness in the world, Min—if all women were like you”, says Jack. “Perhaps they would be—if it wasn’t for the men”, Minnie replies. It’s an intelligent reply, whose weight of meaning is lost on Jack. For him, it’s a matter of men “guessing” women: “I’m glad I guess right”, is how he concludes his philosophy. Minnie goes to the record player and puts on a record: “Happiness” is the song. The music plays. She smiles. She looks over at her sister and the sister’s boyfriend, snuggling on the sofa. Her smile extends, then fades. She takes in a deep breath. Before she exhales, there is a cut. We see Jack, his eyes wandering without object, smoke rolling in his mouth, his fingers drumming his knee; he almost turns to look over his shoulder. Cut to black. Fade in: The End. This scene is one of the film’s finest. Jack and Minnie stay locked in their own thoughts—hers clearly deeper than his. Each are poised for some expression of thought that is never given.

Paul Cuff