This week, a glamorous production overseen by Erich Pommer for Ufa in 1925. A young, starry cast, glorious sets, fabulous locations – and music. What more can one ask for? Ein Walzertraum was adapted from the eponymous operetta from 1907 by Oscar Straus (1870-1954) and was originally accompanied by a score compiled from this (and other existing music) by Ernö Rapée. Sadly, like many scores of its era, this no longer survives – a fact that may even have been the result of the difficulty retaining copyright on Straus’s music beyond the premiere performances. (Nina Goslar very helpfully details various aspects of the film’s history, music, and restoration in Stummfilm-Magazin.) For this centenary restoration, a new orchestral score has been commissioned from Diego Ramos Rodríguez. Rodríguez worked as assistant to Bernd Thewes on the reconstruction of the original Fosse/Honegger score for La Roue (1923) in 2019, and has more recently composed a rip-roaringly splendid new score for Lubitsch’s Kohlhiesels Töchter (1920). The music for Ein Walzertraum was recorded by the Philharmonisches Staatsorchester Mainz, conducted by Gabriel Venzago in the Staatstheater Mainz.

This film – and the prospect of this superb new restoration – thus has many things that appeal to me. I know a few of Straus’s operettas, especially Die lustigen Nibelungen (1904) and Der tapfere Soldat (1908), as well as some of his orchestral music – and, of course, his later scores for Max Ophüls (De Mayerling à Sarajevo (1940), La Ronde (1950), Madame de… (1953)). I had also seen and been utterly charmed by another Berger film, Walzerkrieg (1933), and am interested in the “operetta film” more generally. (Willi Forst is a favourite director of the 1930s-40s.) All in all, then, I was so hooked by the idea of this film that I thought I would go to Germany to see it – and work out some other research to do around the concert, thus justifying the trip. Alas, everything I had planned apart from the concert fell through, so I no longer felt it justified the expense of going. (I received the final blow to my plan two days before I would have to leave, by which point the price of everything had also gone up considerably.) Ironically, the one thing I had booked and had to sacrifice was my non-refundable film concert ticket. It was a good seat, too. (I would have it no other way.) Thankfully, ARTE has since put the film on their mediathek page, and one may watch for free. I have watched, and – inevitably – I loved it…

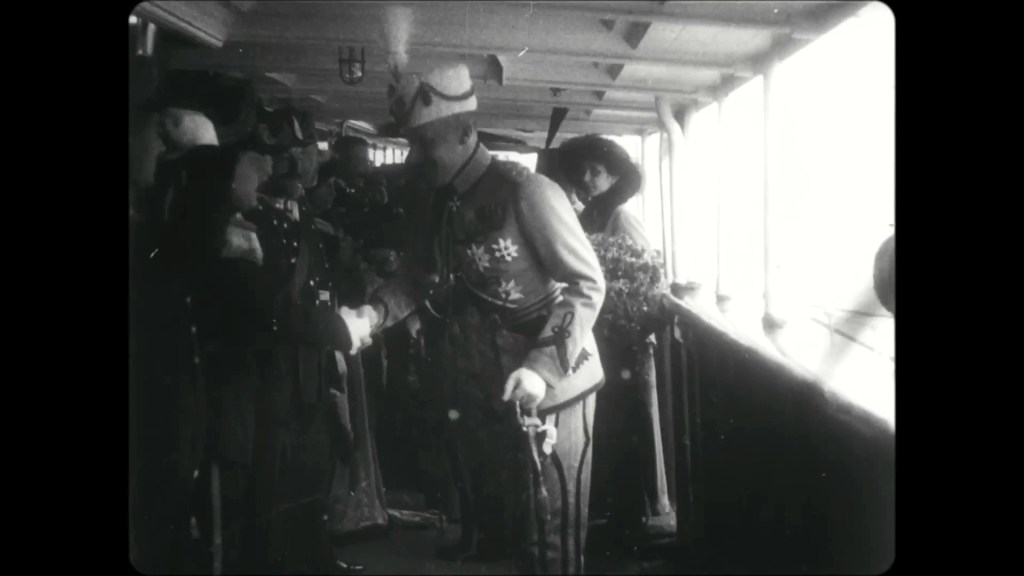

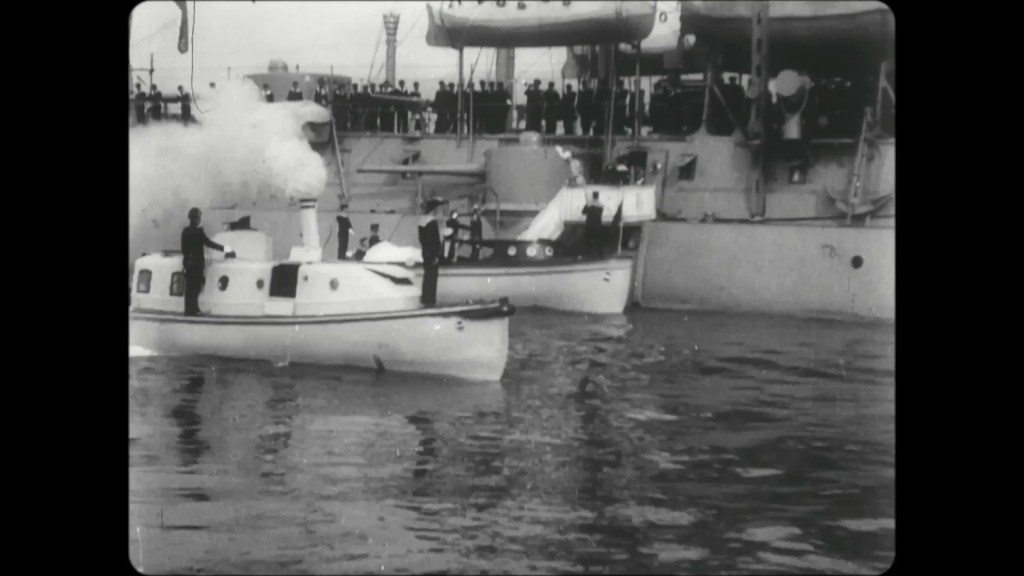

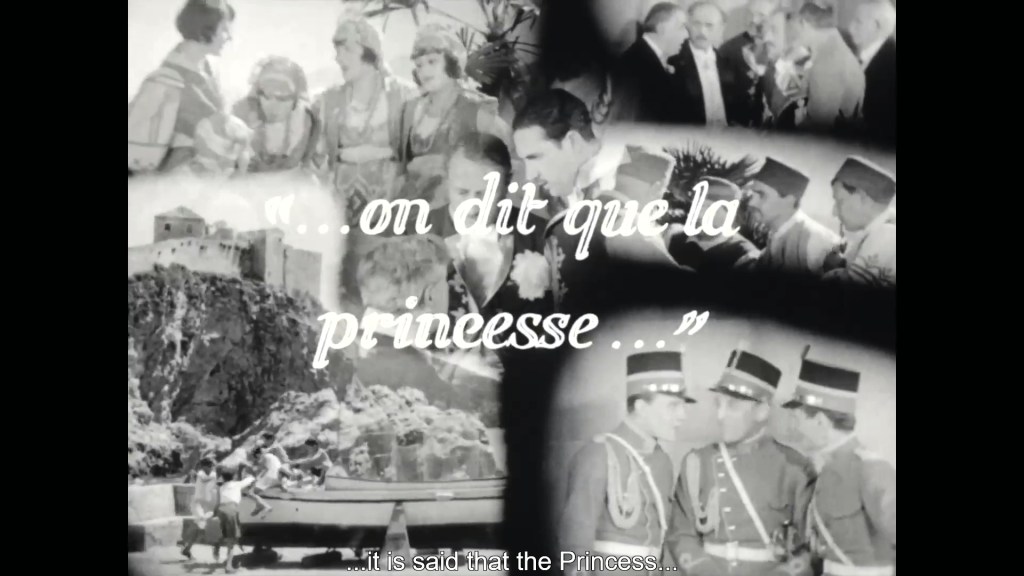

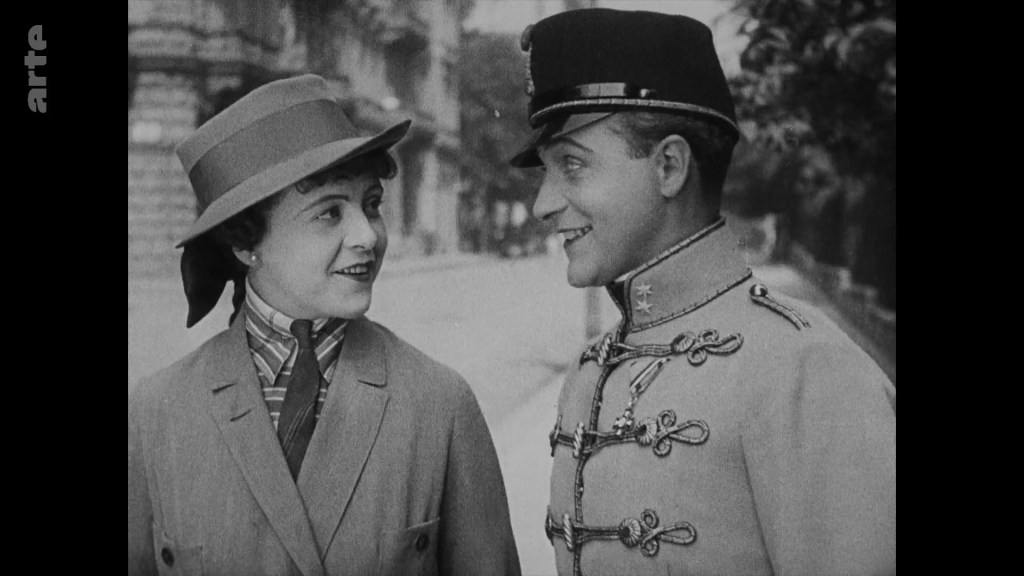

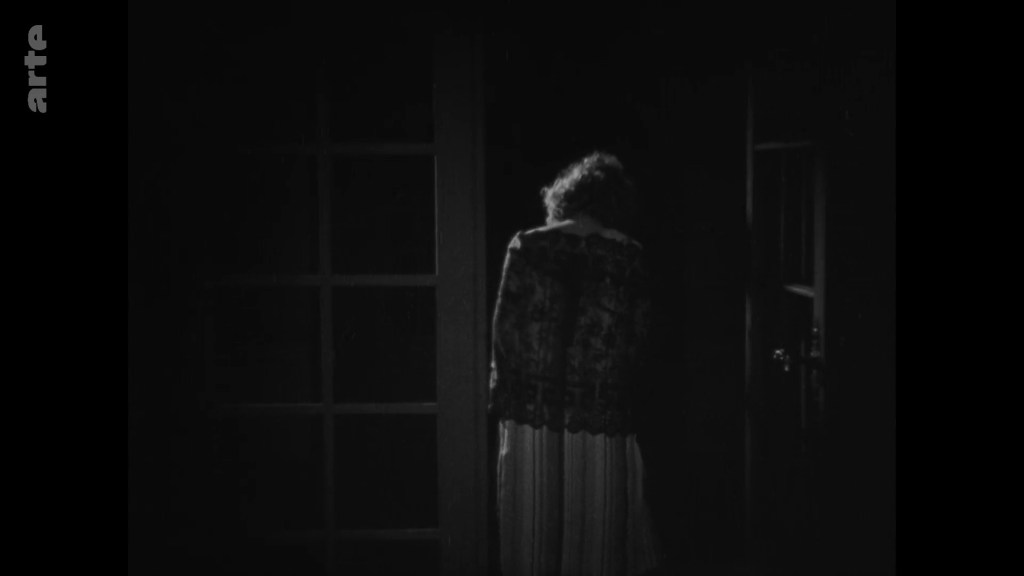

The Archduke of Austria (Karl Beckersachs) is engaged to Princess Alix (Mady Christians), daughter of Eberhard XXIII von Flausenthurn (Jakob Tiedtke). But the match is not a happy one, and when the Archduke’s adjutant Nikolaus Preyn, known as “Nux” (Willi Fritsch) is substituted to take Alix on a tour of Vienna, the pair soon fall for each other. Eberhard swiftly re-arranges matters and has Alix marry Nux – and move to Flausenthurn. But the hastiness of it all gives Nux cold feet, and he abandons his bride on their wedding night. In the Piesecke biergarten he meets Franzi (Xenia Desni), the leader of a women’s orchestra. Franzi doesn’t realize that Nux is married, so a romance ensues. Meanwhile, Alix wants to make herself more appealing for Nux, who clearly misses Vienna and all things Viennese. She engages Franzi, her official Kapellmeister, to teach her the waltz – and modern fashion. With his bride and his new home transformed into a more Viennese environment, Nux’s desire for Alix is reignited. But he must break things off with Franzi, who finally realizes the truth about her lover. The last image is not of the embracing couple but of the lone Franzi, walking into the darkness. ENDE.

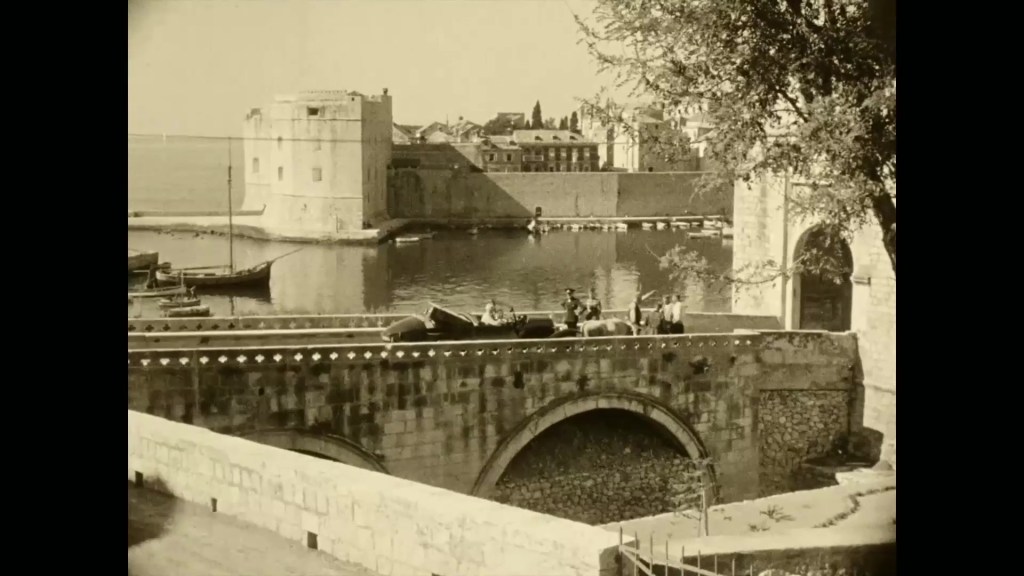

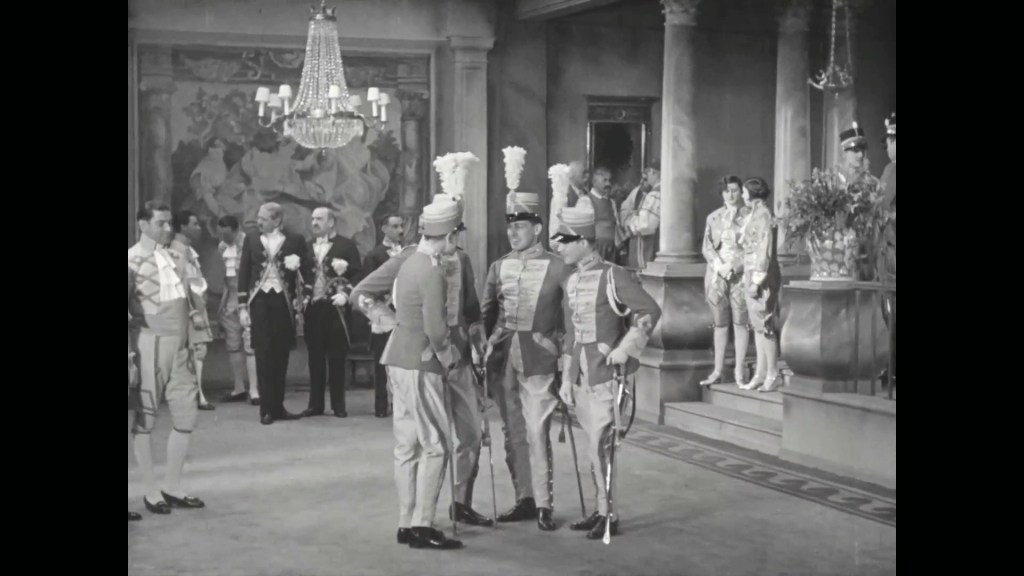

This is a fabulous film. As one might expect from a mid-1920s Ufa production managed by Pommer, Ein Walzertraum looks gorgeous. The sets are superb, the lighting and camerawork superb, and the location shooting in Vienna superb. There are also some lovely passages of multiple superimpositions (often in combination with models/matte painting) and delirious kaleidoscopic lens effects. But despite all this, it doesn’t feel weighed down by its artifice. It has enough (real) fresh air to give it the breath of life, and of a sense of past and place that infuses its setting and characters. It is, per the cliché of numerous such films (and operettas), set in Vienna c.1900 – and then in the Ruritanian principality of Flausenthurn. (In the original operetta, this was in the state of “Rurislavenstein”.) Thanks to the use of real locations, one has a little more belief in this world – and can wander around the parks and streets of Vienna. It has the budget and the technical prowess to give us a world that feels rich and peopled.

The cast is also very good, with some of Ufa’s youngest stars taking the lead. Willy Fritsch’s Nux has all the boyish charm you could wish for, but also has moments of emotional depth – or at least, moments when he senses that his boyishness comes at a price for others. As Franzi, Xenia Desni is very sweet – and you can see why, with her backlit halo of hair, her sentimental music, and her earnest happiness, Nux falls for her. I admit that I was not as moved by her as a performer, as a presence on screen, as I was by her female co-star…

Indeed, the real highlight of this film’s cast is Mady Christians. This is the earliest film in which I’ve seen her. Even by the end of the 1920s, I’m used to her being a very adult, very sophisticated screen presence, one radiating intelligence and a kind of tolerant, patient superiority. It was something of a surprise to see her looking so much younger here in Ein Walzertraum. Younger not just in terms of her looking more girlish, but younger also in the sense of character. (One might also say in terms of star persona.) She still has amazing flashes of intelligence and insight, but she’s also far more emotional – and vulnerable. She’s also playful in a much more fun, childish way. In one early scene, she loses patience with her father and wrinkles her nose at him like a naughty schoolgirl. It’s a lovely moment where her frustration breaks out into comic exaggeration.

Christians also plays drunk fabulously well. When Nux takes her to the biergarten, her surprise and delight in tasting beer, then in becoming embroiled in the rowdiness of her surroundings, is such a pleasure to watch. Her kiss with Nux seems at once inevitable (in the way you see it coming) and sudden (in the way it happens so brusquely on screen). Alix watches the schmooziness of other dancers, then places her head drowsily on Nux’s chest, slowly angling herself (and her mouth) closer to him (and his mouth). He finally steals a kiss, and the slow play of anticipation is suddenly ended. “What was that?” Alix demands. “That was Viennese!” Nux replies. It’s funny and touching all at once.

But it’s the aftermath of this scene, when Alix goes back to her room at the palace, that shows Christians at her most playful. At home with her chaperone Fraulein von Köckeritz (Mathilde Sussin), she is lounging on the bed, dreamily, gigglingly reliving all the thrills of her evening. Christians is very funny here, but she’s also (if I may say so) very sexy: her glance, her smile, her slightly giddy enthusiasm. She is not just a schoolgirl but an adult, with adult desires. She even makes rather more than a pass at Köckeritz – first kicking her (by accident), then crawling over to her, kissing her, dancing with her, and kissing her again. Christians is wonderful here, but also in the alter scenes, when her hurt at being rejected by Nux is palpable: she’s an adult again, with adult depths.

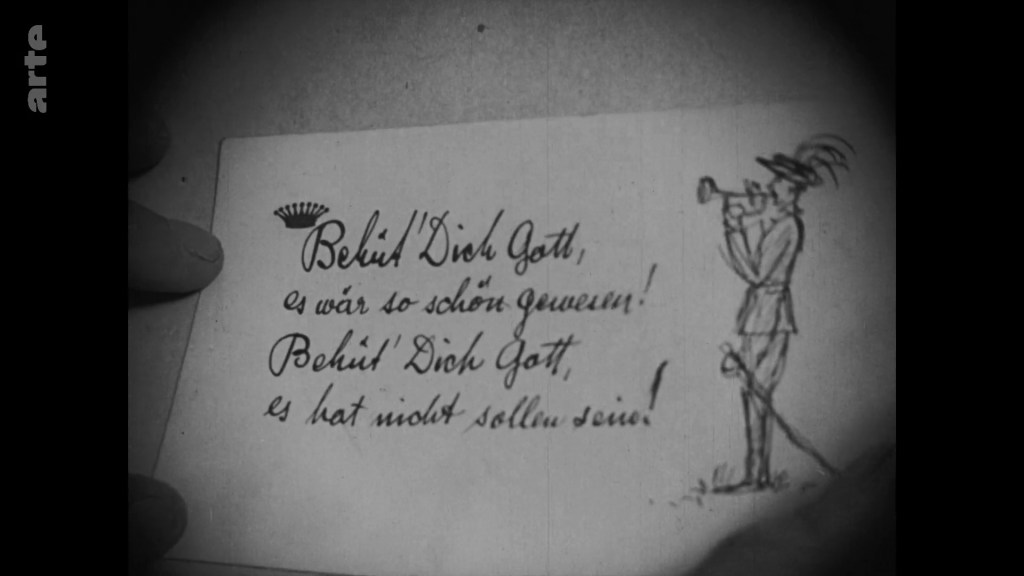

Among the remaining cast, I would also praise Julius Falkenstein, who plays the servant Rockhoff von Hoffrock with comic exaggeration (per his comic romance with the bassist Steffi (Lydia Potechina)) and with surprising emotion later on, per his finding the note from Nux that he thinks is destined for Alix. In the latter scene, he is hurt that Alix will be hurt – a fact that adds depth (and personal history and loyalty) to the consequences of Nux’s affair.

But what make the whole thing work so well as a viewing experience is the way image and music work together in this restoration. It makes all the reasons why the film might work into an experience that does work. Rodríguez’s score is for a symphony orchestra, including a piano and harpsichord (and various other percussion). His score uses much Viennese music of the period, as well as some actual musical samples from historic recordings, and one or two subtle sound effects. Rodríguez has an interest in electronic music in his other work as a composer, but I feel that he has bent his style to this film rather than vice versa. I found myself rather won over by the way he incorporates unusual elements into the soundscape of Ein Walzertraum. He’s also a great orchestrator, able not only to cite repertory music with great skill, but to play with its mood, texture, and rhythms. There are many moments when the sweetness and neatness of the music frays at the edges, threatening to dissolve into something harsher. Rodríguez knows how to maintain control of uncontrol, and to switch between registers and tones.

This balance between old and new, the expected and the unexpected, is evident early on. After their comically protracted scene together, Alix and the Archduke walk away, disappointed and awkward, through a path flanked by huge hedges. The wind rustles the branches, and the score magically rustles with energy. The sound of the harpsichord, almost discordant, crackles beneath the woodwind, and a subtle sound effect – only just discernible – flutters through the instruments. It’s somewhere between the rustle of wind-blown leaves and the crackle and hiss of a needle on vinyl. It catches you unawares, and I found it weirdly effective.

After the Archduke excuses himself, Nux is ordered to take Alix on the tour of Vienna. This is an utterly enchanting sequence. The camera tracks alternative before, alongside, and behind the carriage. It cranes up at the theatres and spires, drifting through the Vienna of – not 1900, but of 1925. The people on the street are clearly staring at the camera, at the stars, at the people in imperial costume. Reality bubbles at the edge of the fiction. And so too in the score. Beneath the gorgeously slow waltz there seems to be a gentle, only just audible, patter of hooves. The sound is so subtle it might be an extra instrument, a softened rattle over a drum. When Nux shows Alix the statue of Johann Strauss II (“Your Highness, the Waltz King!”, he says; “We have a dance violinist in Flausenthurn too!”, she replies), we get a refrain from that composer’s “Wiener Blut”. But it’s not just the choice of music here that works, it’s the way the score – as a soundscape – adds to this moment. As the pair approach the statue, the music is underlined by the faint crackle and hiss of (what sounds like) ancient vinyl. It’s a very subtle effect, as though something is burbling in the background of the orchestral music. Suddenly, the scene draws on another level of cultural memory. It’s not just the memory of Strauss, but the memory of the memory. It is 2025 remembering 1925 remembering the nineteenth century. Beautiful.

Later, Rodríguez brings in a delightfully jazz-inflected rendition of various traditional tunes for the wine tavern scene. Decorum starts to unbutton here, as the princess and lieutenant encounter working-class revellers, soldiers, and fortune-tellers. Rodríguez also incorporates the clapping of the orchestra into the soundscape, timed perfectly with the clapping-along on screen. (It’s utterly infectious, and I would love to know if anyone at the Mainz performances tried to join in.) Later, when the servant turns up and interrupts their dance, exclaiming: “Your Highness!” the score matches the unease of the working-class crowd, who suddenly stop dancing and stare, then awkwardly begin to hail royalty. The music brings in a brief burst of (Johann Strauss I’s) “Radetzky March”, like a splash of cold water to sober up the revelry.

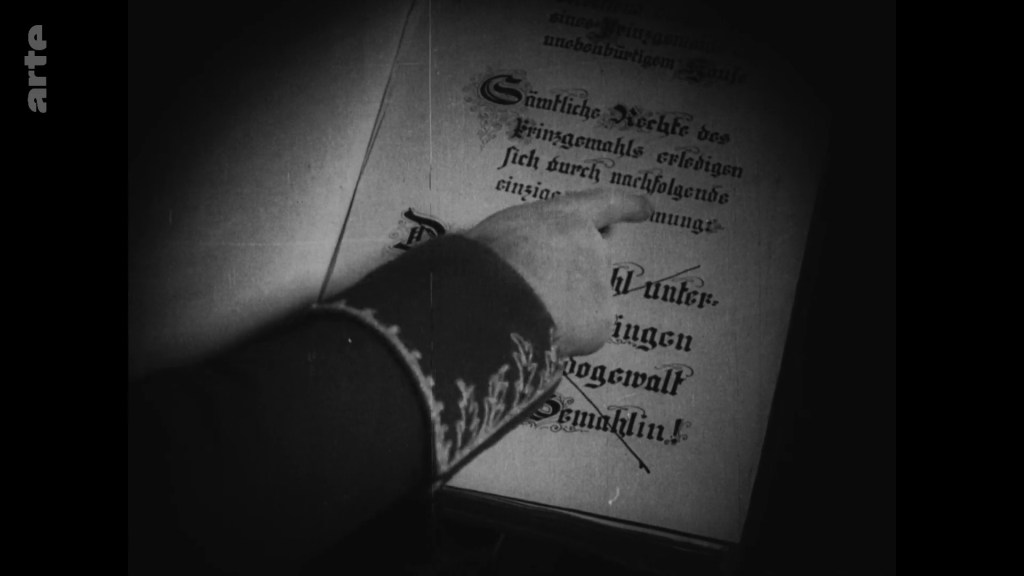

If there is fun and wit here, I also love the choices enhance the emotional depth. As Alix prepares for her wedding, Rodríguez cites a few bars of the second movement of Schubert’s Symphony No. 8 for the wedding preparations. It creates an immediate sense of solemnity that is brief but deeply moving. It’s suddenly very serious and meaningful. During the wedding itself, I also noticed a familiar Monteverdi fanfare (the opening toccata from L’Orfeo (1607)). I recalled Günter A. Buchwald’s recent use of this piece in his score for Casanova (1927); there, I didn’t like the way it was used for the harsh irony of its orchestration and employment, in absolute contrast to the tone of the film. See the difference to how it’s used here by Rodríguez inEin Walzertraum, which is delightfully pompous and in accord with the elaborate ceremonies that the servant relays via increasingly lengthy (and absurd) intertitles. The music is taken seriously, which is the point of the sequence – the pomp of the past, the pomposity of the court and its king. But it doesn’t stop the sequence being funny, indeed it enables it to be both funny and moving.

Rodríguez also knows when to step back, as when here he keeps the music rumbling at a low level through the elaborate “elevation” of Nux to noble status to marry the princess. It lets the film do the talking. We are told that this is “the wedding ceremony according to the House of Flausenthurn Regulations of the year 1611”. The list of ceremonial steps is so madly long that the scroll bearing this text soon whizzes past on screen. It’s very funny, and the score here incorporates part of a 1926/27 recording of tunes from Straus’s Ein Walzertraum. The sense not only of pastness but of ceremony is perfect: it’s an old, old celebration reliving itself, the recording both lively and ancient.

But then the Schubert is used again at the end of the ceremony, and the solemnity of it – and what Alix dreams it to be – sinks in. It’s a brilliant, beautiful choice. The wedding is also going to be “unfinished” in its unconsummated aftermath. The management of tone here, and throughout, is simply superb. Listen how Rodríguez adds the snare drum beneath Schubert’s haunting theme for woodwind, then suddenly switches to a Straus(s)ian melody on the glockenspiel, and then – for the “tearing of the bridal veil”, per the house regulations – weird percussive sounds and drums as Nux tears and tears and tears. There’s so much going on here: the solemnity, the air of childishness (and of inexperience), the expectation, the nervousness, the frustration, the pent-up energy… all incorporated into the music with great sensitivity and intelligence.

Nux’s romance with Franzi is also felt through the music. In the biergarten, the synchronization of Franzi’s female string group to “Wiener Blut” is perfect. (The programme for the concert on screen is even revealed in the notes Nux finds on his table, so the new score can clearly take its cue from this.) Franzi then takes her cue from Nux, who requests a Viennese waltz. Here, the score includes a historic recording of Strauss II’s “G’schichten aus dem Wienerwald” sung by Maria Ivoguen in 1923. The film dissolves to Nux’s daydream of the self-same Viennese woods, and dancing maidens, and the distant violinist. The song becomes a kind of dreamed sound, emerging from the film – even from the mind of Nux. (The film builds up the visual reverie with multiple superimpositions, kaleidoscopic effects of blossoms falling, piling up, and swirling like an abstract waltz.)

Meanwhile, Alix is learning the piano. She has chosen something marvellously assertive, a piece whose acoustic effect is surely beyond that of a piano reduction. There follows a brilliantly reorchestrated version of this very piece, “The Ride of the Valkyries”, with a manic piano accompaniment. It’s an amazing moment, funny and sad and furious (and sexual) all at once. It’s a woman expressing her rage and longing, the music and her emotions quite literally making the furniture quake with power. Rodríguez again shows great skill in keeping (musical) control of this outburst of uncontrol. Wagner’s music is being produced through sheer willpower, with only just enough skill to make it recognizable. The orchestra battles with the piano, which battles with the score; it’s a mess of fury and melody in sound.

When Nux and Franzi dance in her apartment, her friend Steffi plays the piano. On the soundtrack, a real piano accompanies a historic recording of “Leise, ganz leise” from Straus’s Ein Walzertraum, sung by Max Rohr in 1907. I love how complex this moment is: a real piano on screen being echoed by a real piano in the orchestra but accompanying a historic recording from the era of the film’s production. The idea of different eras, different styles, talking to one another is nicely echoed in the subsequent scene when Franzi teaches Alix a waltz on the piano. The princess’s rendition of “The Ride of the Valkyries” marvellously morphs into this waltzing melody.

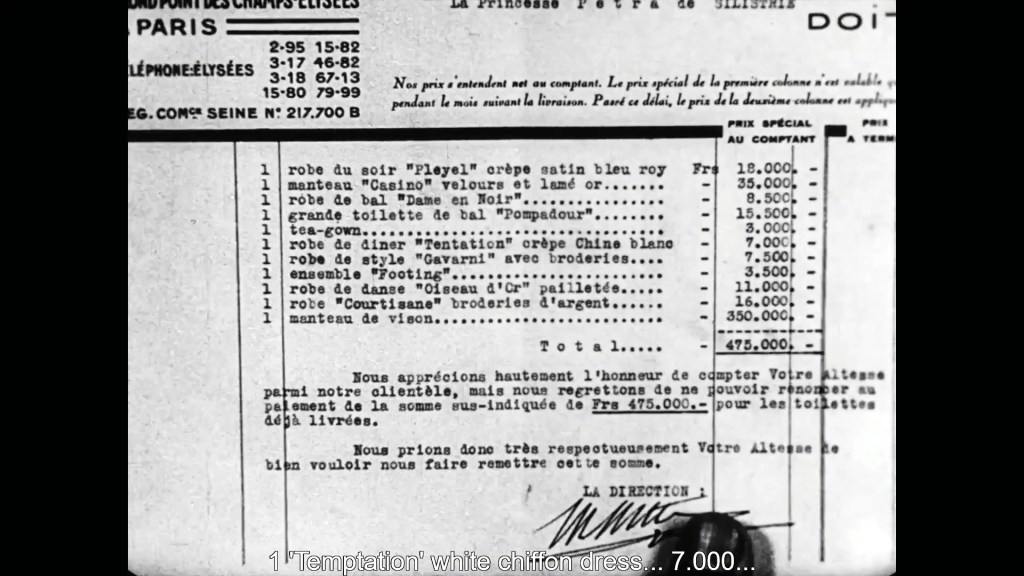

Franzi then refashions the princess to make her more appealing to her husband. This activity begins with Alix openly admiring Franzi’s legs as she bends over the piano. As in the earlier scene, the princess is rather curious about another woman – and aroused. Wanting to be more like Franzi, she puts herself in her (unwitting rival’s) hands. The two women undress each other, in order to then try on each other’s clothes. At first this extends just to the outer dress, then (as Franzi realizes how many underlayers Alix is wearing) to the underwear. As they do so, Nux’s biergarten note falls from Franzi’s garment to the floor. Alix picks it up and reads it and the pair exchange smiles. With its blend of role-play, sexual suggestion, and dramatic irony, this is an amazingly complex sequence. (It becomes more complex, and funny, as Franzi then returns to the biergarten to find Nux leading her band in a waltz.) Indeed, Nux later interrupts the two women dancing – a male intrusion into what might otherwise be an all-female romance. The fact that Alix is given a short, “Bubikopf” bob haircut (the very definition of 1920s’ women’s fashion) signals her liberation from an older, more traditional form of femininity. “Ich glaube, jetzt bin ich modern!” (“I think I’m fashionable [literally: modern] now!”) she says after Franzi has finished with her. It’s an intriguing scene of possibility, of alternatives for her desire – beyond her desire for Nux.

The outcome of the above scene is also intriguingly played. Alix has made herself attractive to Nux by mimicking Franzi’s appearance, and the way she reveals her new self – by half-hiding behind a chair, by leading Nux on, allows Christians another chance to show the sophistication of her performance. The film also plays on the fact that Alix is unwittingly recreating the very facets of her rival that drew her husband to Franzi. Alix’s gesture of retrieving her lighter from inside her top echoes Franzi’s retrieving of the note inside hers. (Meanwhile, Franzi echoes Nux’s gesture of tearing the bridal veil as she tears and refashions more of Alix’s clothes in the next room.) But instead of Alix consummating the marriage with Nux at the end of this scene, Alix ends up kissing Franzi in thanks for transforming her life. Across much of the flirtatious reconciliation of Alix/Nux, we hear the “Couplet der Ninon” from Straus’s Eine Frau, die Weiss, was sie will, sung by Fritzi Massary in 1932. But Rodríguez’s musicians in 2025 provide the orchestral force behind (and to some extent over) this historic recording. Indeed, the rumbunctious orchestra threatens to overwhelm the (female) voice, as Nux’s blood is up and he chases Alix around the room. There is comedy here, but also a faint air of threat. (Here, as so often, you have to admire the orchestration, which seems on the brink of disintegration into some far wilder, less tonally coherent.) It’s another incredibly suggestive way of using modern and historic music together, producing not just a pleasing sound but a sonic (and thus dramatic) tension. It also nicely echoes the film’s introduction of Nux, when he was chasing a woman around his office. Over this early scene, the orchestra accompanies another historic recording of “O-La-La” from Straus’s operetta Der lezte Walzer, sung by Fritzi Massary in 1920. Rodríguez’s score thus repeats the pattern of movement (a kind of barely-controlled waltz as man and woman chase each other round and round) and the pattern of musical citation.

In sum, I loved Ein Walzertraum. I admit I’m an absolute sucker for this kind of thing, when it’s done well. And it’s certainly done well here. This is a fantastic film, and a fantastic score. I normally don’t like music that uses pre-recorded material, i.e. sounds/sound effects, but here it is sensitively done – and often adds to the complexity of the viewing experience. These sections also nod forward to the many operetta films of the 1930s, of which Ein Walzertraum was a major predecessor. How I wish I’d been able to experience this film on the big screen in Mainz, with the orchestra and the crowd. I’d like to know how the pre-recorded sections of the score interacted with the orchestra (and the live acoustic), and how the audience reacted to these moments. Even if I didn’t get to sit in the seat I bought, I’m glad to have offered some token of support to the restoration and those who brought it about. Bravo to all involved.

Paul Cuff