Day 3 of the Stummfilmtage Bonn takes us to Czechoslovakia in 1929. Both the film and its director were new to me, but I’d seen this restoration doing the rounds at various festivals and wondered if it would ever come my way. I was therefore very happy to see its inclusion at the Bonn festival – it’s exactly the kind of film I’d hope to encounter…

Varhaník u sv. Víta (1929; Cze.; Martin Frič)

The plot is a marvellously strange melodrama. The organist of St Virus cathedral in Prague is an old man whose only joy is his music. One night, his solitary evening is interrupted by an old friend who has escaped from prison. The friend has a daughter, for whom he has a bundle of cash and a letter. After entrusting these items to the organist, the friend shoots himself. The scene is witnessed by a neighbour, Josef, who manipulates the organist into burying the body in his basement while he makes off with the letter. Later, the organist visits his friend’s daughter, Klara, who lives as a nun. He gives her the money and tells her of her father’s death. Shaken, Klara wants to know more – but the organist refuses to explain. Dreaming of a different life, and haunted by her father’s mysterious death, Klara leaves the nunnery and finds shelter with the organist. The organist becomes a kind of surrogate father, but he is tortured by the presence of the body buried in his basement. While Klara pursues a romance with Ivan, a handsome painter whom she has seen outside the convent, the organist is confronted by Josef, who tries to blackmail him. Josef then tells Klara that the organist was murdered by the organist. Klara flees to Ivan, while the organist has a mental breakdown and finds his right arm paralysed. Unable to settle with Ivan unless she knows the truth about her father, Klara returns to the organist’s home and finds her father’s grave. Horrified, the organist locks her in – but Ivan rescues her. Josef witnesses the torment his lie has caused, so sets out to right his wrong: he tells Klara the truth and apologizes to the organist. A miraculous cure enables the organist to recover the use of his right arm, and the film ends with him playing music at the wedding of Klara and Ivan. KONEC (The End).

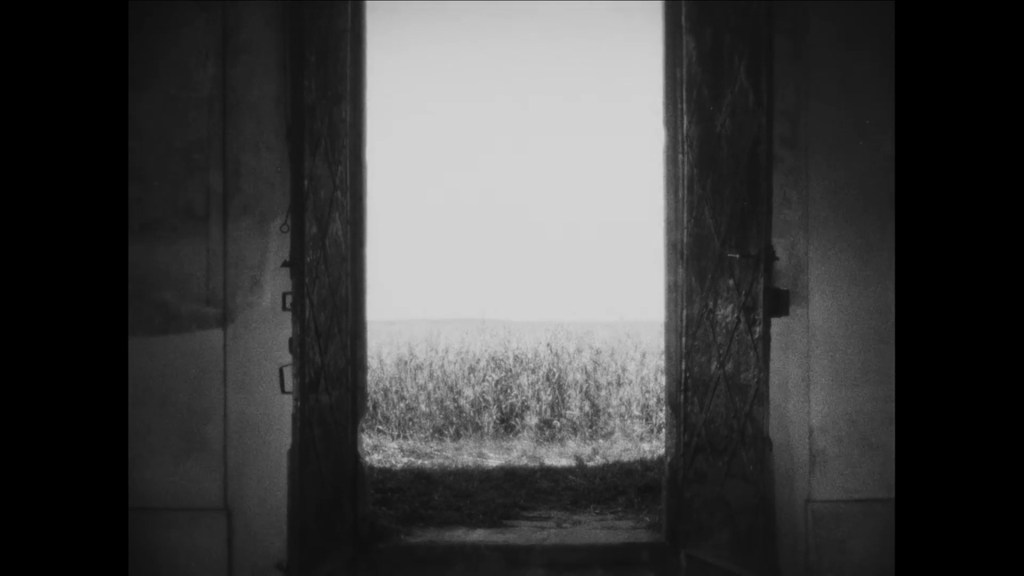

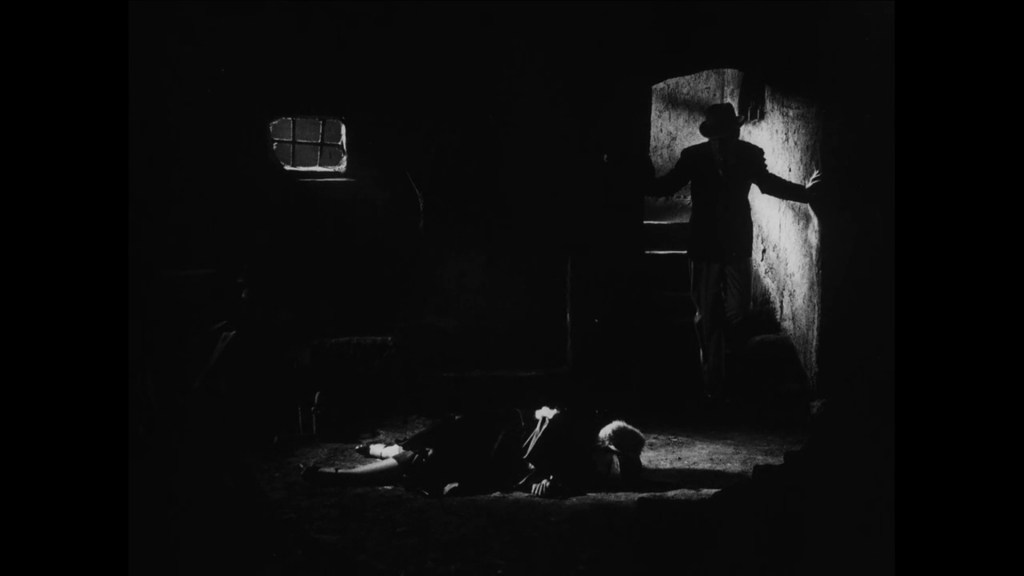

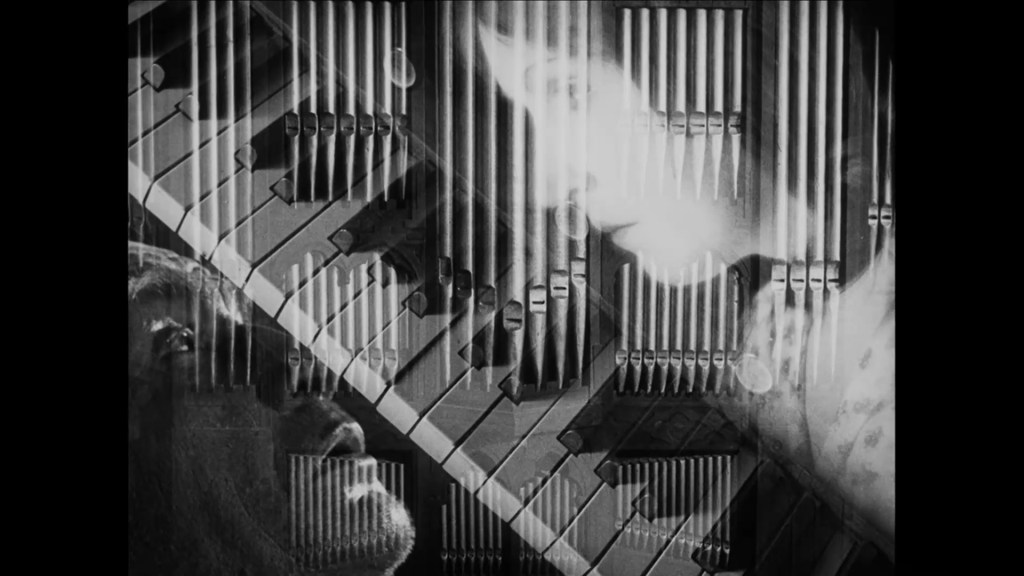

Though it has taken a lengthy paragraph to explain the convoluted plot, the film itself is far from novelistic. Titles are kept to a minimum, and the film is an overwhelmingly visual experience – its lush photography and vivid set pieces doing all the heavy lifting. I absolutely loved the panoramas of Prague and the cathedral. These would have a documentary beauty of their own, but Frič overlays them with superimposed images and subtle gauzes/mattes to transform these views into something stranger, more lyrical and evocative. We see Prague and its streets and monuments the way characters do. Thus, the cathedral space and the organ become spaces of monumental splendour and majesty – the site of the organist’s only creative and spiritual freedom. And the monastery interiors are seen through Klara’s eyes: forbidding, geometric, imprisoning networks of arches, bars, grilles. When she gazes outside, the fields are luminous, shimmering visions, the sky’s soft-focus glow shaped through subtle matte painting into dreamy, sunbeamed expanses. The streets around the organist’s cramped home are an expressionist maze of bright streetlights and thick shadows, with figures negotiating sheets of rain and glimmering cobblestone roads.

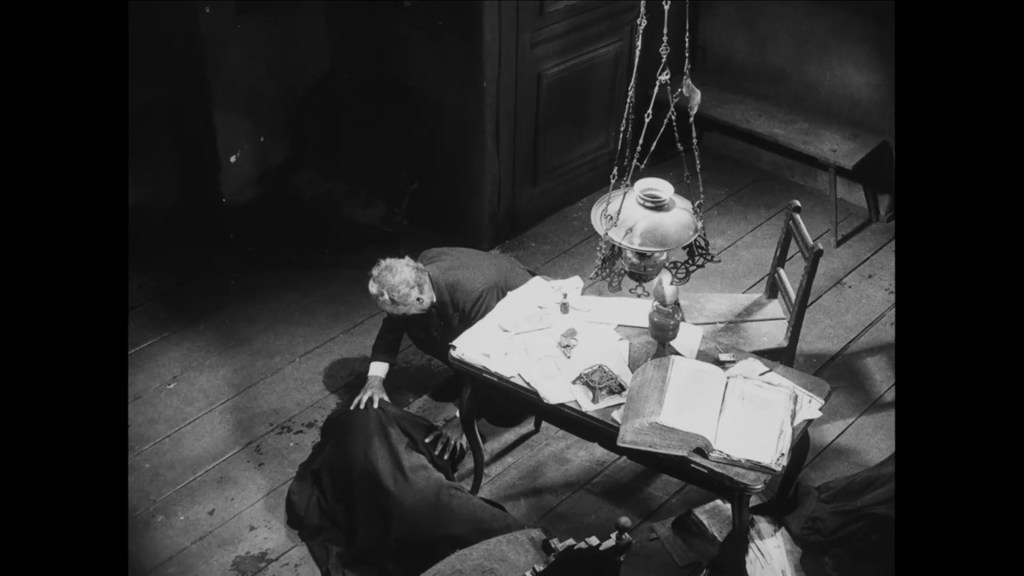

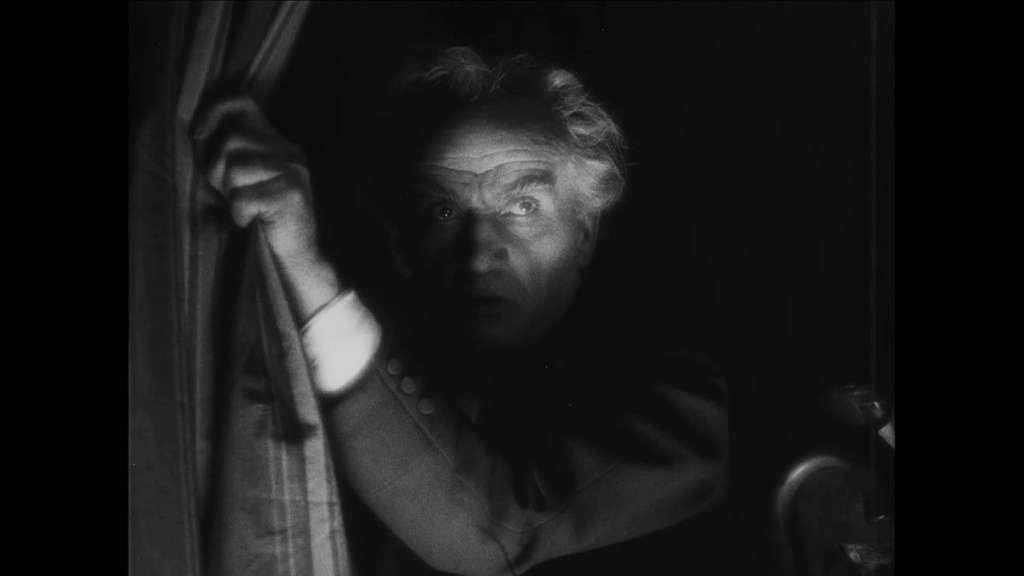

The interiors are no less splendid. In particular, the organist’s cramped house is often filmed from a low angle, the camera crouching at floor level to observe the space. The effect of this is to create a sinister and foreboding feel to the setting – as if we were an illicit observer, half-concealing our presence. But it also serves to makes the viewer conscious of the floorboards and think of what lies beneath. Even if the scene itself is not directly concerned with the fate of Klara’s father, the camera position reminds us of his body lurking below stairs.

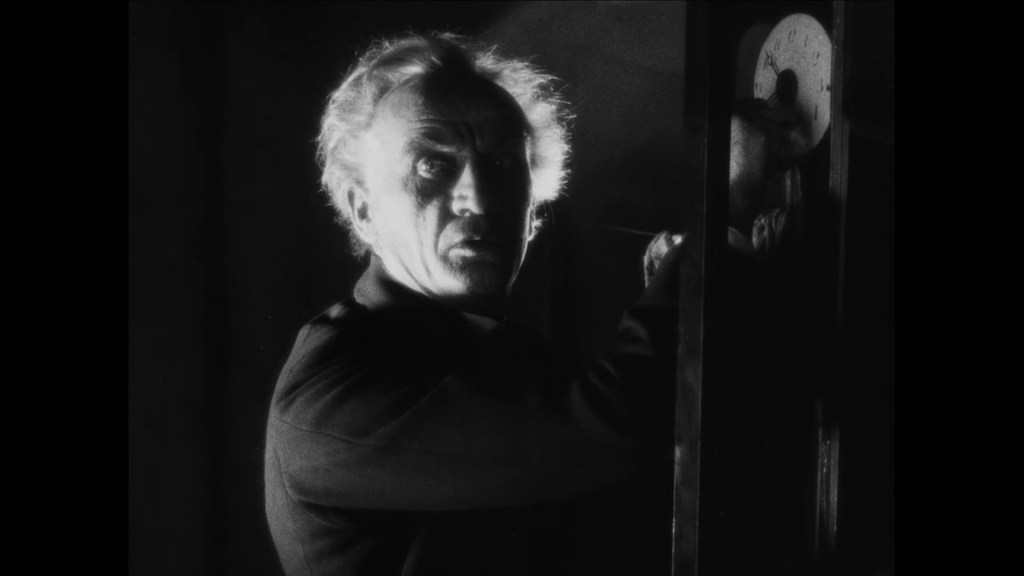

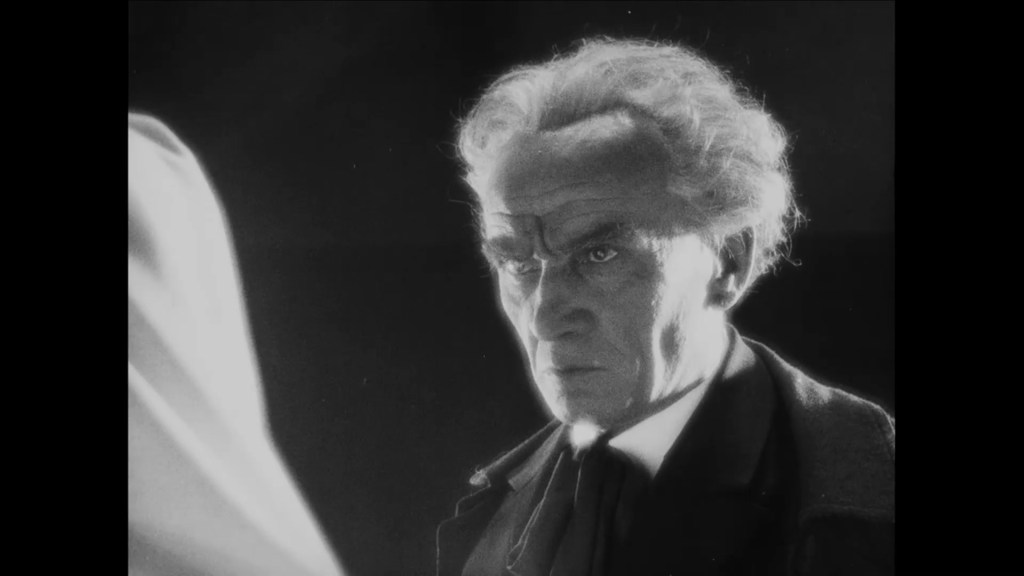

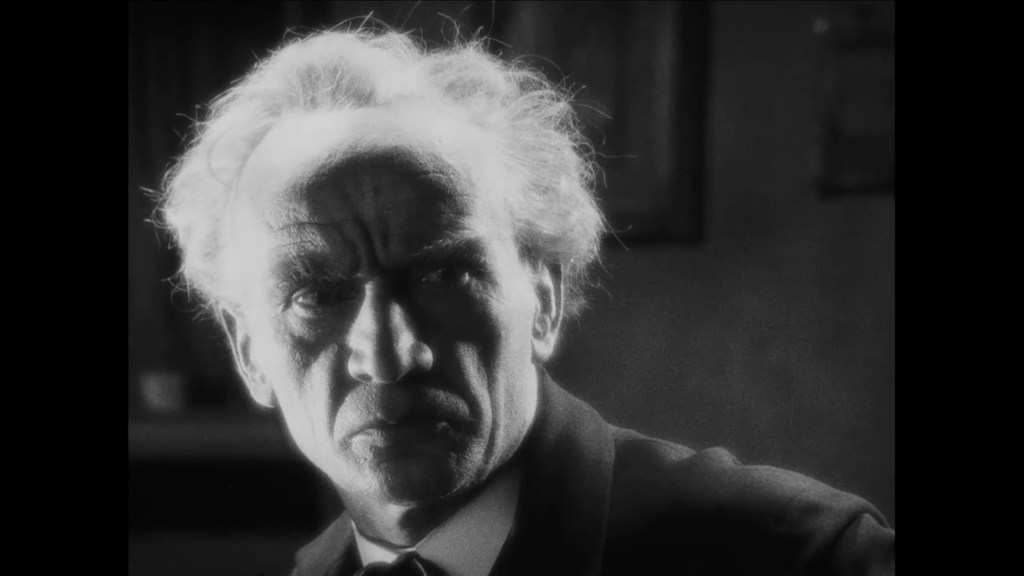

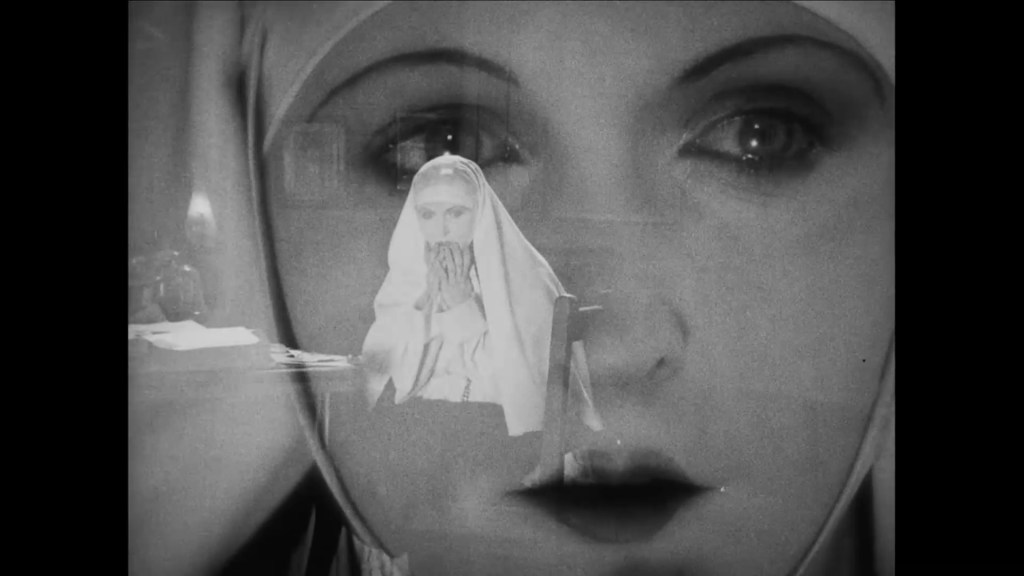

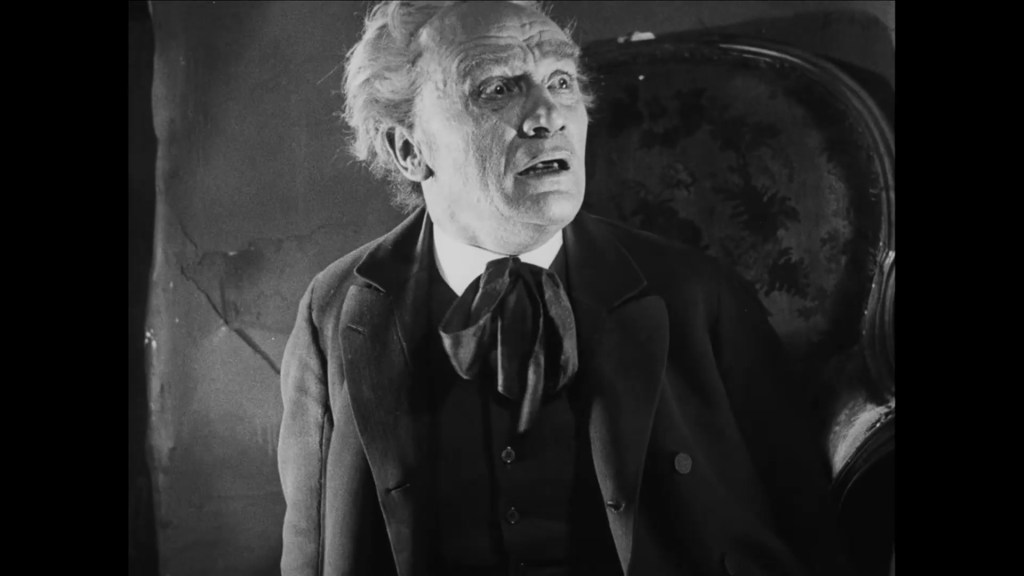

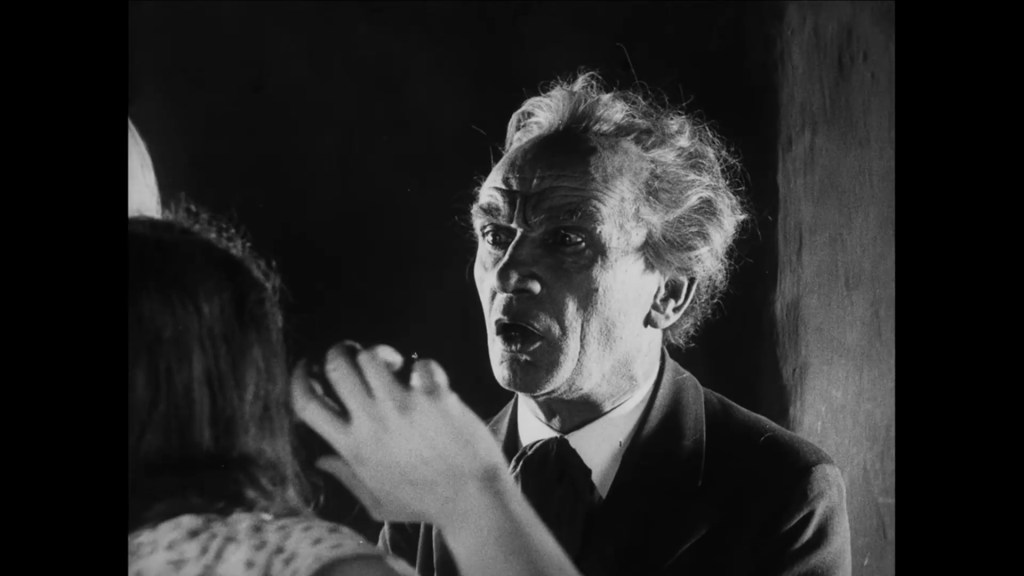

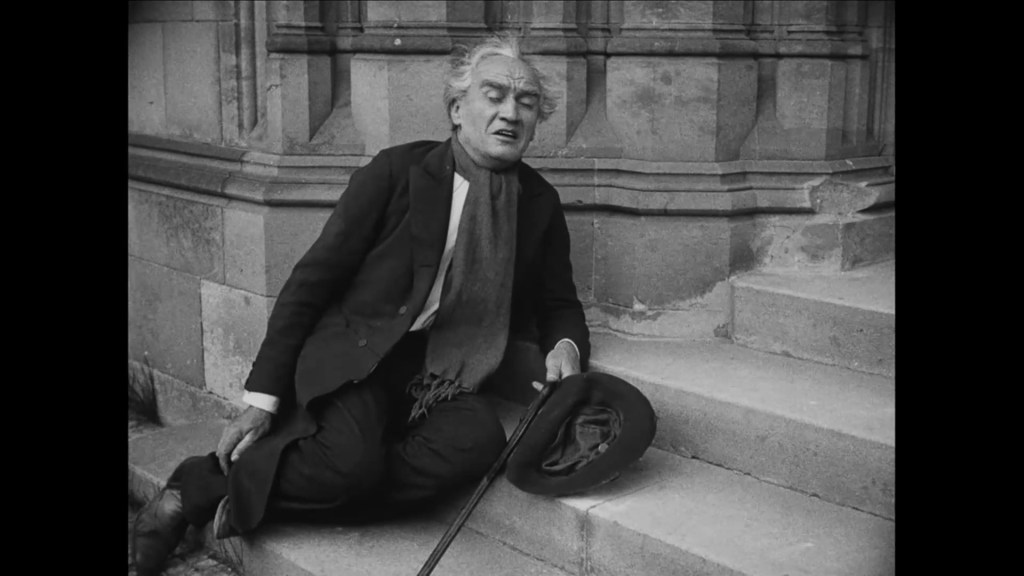

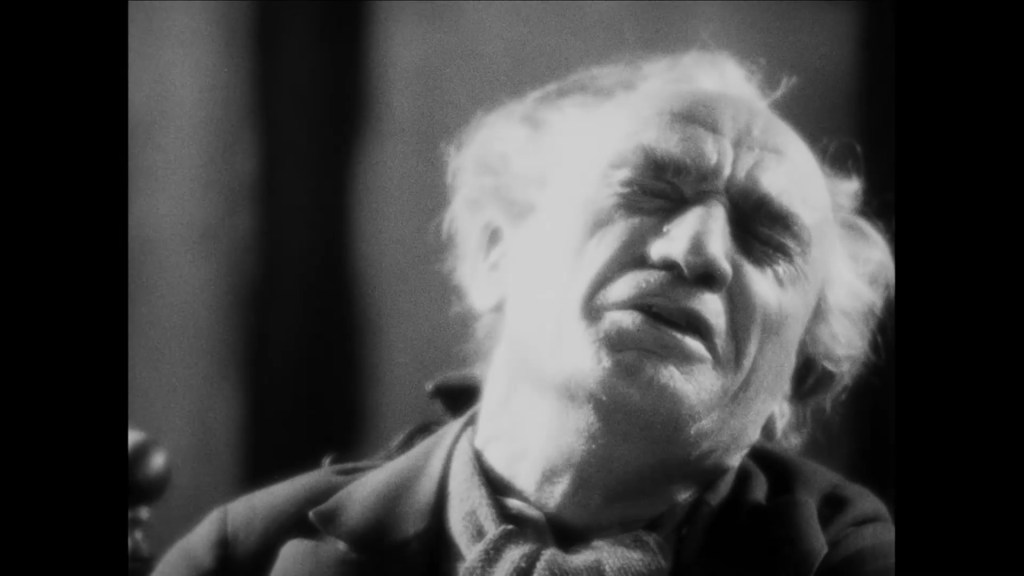

There are some superb close-ups, too. The organist’s white hair is turned into a sinister halo around his darkened face. Josef’s plotting eyes flash from wreaths of smoke. Klara’s eyes brim with tears in the centre of her pale, pale face. Even on a small screen, these images are strange, powerful, mesmerising. I love the way Frič dissolves slowly between shots, so that images linger over one another. He often overlays a close-up of a character looking with an image of what they see. The effect is both startling and immersive, subjective and objective. It’s a rich, lush, entrancing visual language.

The performers are all highly engaging and I enjoyed spending time with their faces. As Klara, Suzanne Marwille begins the film framed in white wimple and habit. She’s a vision of isolation, but her eyes shine in the middle of her pale face in her white clothing. She then transforms into a homely, traditional figure of a young women when she lives with the organist: summer dress, a head scarf containing her long hair. Then she lives with Ivan and is transformed again into a modern woman of the 1920s, with a Louise Brooks style bob and shimmering black dress. (She even sports her nun’s outfit to model for Ivan, as if to remind us of the sartorial and spiritual journey she’s traversed.) While I never warmed to the slightly smug character of Ivan (played by Oskar Marion), their romance amid the glowing, soft-focus splendour of bucolic exterior spaces was gorgeous to look at – and entirely took my mind away from how much I liked or did not like Ivan as a character. As the relatively minor character of Josef, Ladislav H. Struna brought surprising depth. It was much to his and the film’s credit that this very sketchy character went on an emotional journey that was in any way creditable. By the end, as Ivan weeps at his guilt and falls on his knees to beg forgiveness of the organist, I was surprisingly touched. It was nice to see a villain genuinely moved to reform (and sweet to see him cleanly-shaven and well-dressed to go to tell Klara the truth!). Of course, as the lead character of the organist, Karel Hašler had the most dramatic weight to bear. He has a superb face, and you could read every emotion in his eyes and on his mouth. If the melodrama threatened always to overboil into camp, Hašler always seemed to bring it back from the brink.

In sum, this was a highly enjoyable film, aided by a solid musical accompaniment on piano and organ by Maud Nelissen. A splendid slice of late silent cinema.

Paul Cuff