On Sunday I went to London to the BFI Southbank. The reason? To see the UK premiere of the new(ish) restoration of Mauritz Stiller’s Gösta Berlings saga. Having known the film only on its old DVD incarnation, I was excited to see the differences that extra material and tinting/toning would make. I also have memories of being mildly irritated by the Matti Bye score present on the old restoration, so looked forward to hearing the live piano accompaniment from John Sweeney. Delightfully, the presentation took place in NFT1 – Stiller deserves the biggest screen on offer! With an excellent view in the centre of the auditorium, I took my seat…

Where to begin? I suppose with a synopsis. But with Gösta Berlings saga this is something of an undertaking. As he had done with Gunnar Hedes saga (1923), Stiller simplified the Selma Lagerlöf novel on which the film is based – by my god it’s still a complex affair with a shedload of characters. Later I will discuss a few aspects of the plot through its characters, but a brief summary might go as follows: Gösta Berling is a defrocked priest who joins a band of revelling “cavaliers” on the Ekeby estate. He variously attracts and is attracted to a series of women, resulting in much heartbreak and ruin – including to the Ekeby estate. Can Gösta Berling rebuild his reputation and restore the estate to its rightful owner?

The new Svenska Filminstitut restoration was completed in 2022 and adds some sixteen minutes’ worth of footage to the longest previous edition, though it is still another fourteen minutes (approx.) short of the original two-part version from 1924. The restoration credits at least acknowledge this history, unlike those of the recent Svenska Filminstitut version of Stiller’s Sången om den eldröda blomman (1919), which (as I wrote when I saw it) omits any mention of the significant amount of material that remains missing. In terms of viewing the film, the missing scenes from Sången om den eldröda blomman cause less of a problem than the material missing from Gösta Berlings saga. With the latter, the plot is so complex that a summary of what happens in missing scenes (if this information is available) would have enhanced the experience. I remain entirely unclear as to whether the narrative gaps are an issue with Stiller’s skill as a screenwriter or with the gaps in the restoration. (More on this issue later.) As the restoration credits also admit, the pictorial designs for the intertitles of Gösta Berlings saga were not able to be recreated even if the text and font have been. This is a shame, but entirely understandable – and at least the credits flag this absence. But the most obvious difference to the new restoration is the revival of tinting (for the film) and toning (for the intertitles). The film colours are based on a positive copy of the film preserved in Portugal, and the intertitle colour on a contemporary written description, so the overall scheme is likely not identical to the copies presented in Sweden – but this is not a major issue. The main point is that the tinting, in combination with the picture quality, looks stunning. Gösta Berlings saga is a fabulous film to look at. As I’ve written on previous posts about Stiller films, one of the main reasons to watch them is the photography. For Gösta Berlings saga, Julius Jaenzon captures the landscapes in winter and in spring with equal skill. The level of detail, the subtlety of the lighting, the richness of the textures, the artfulness of the composition – it all makes for a great watch. Though I always prefer Stiller when he’s outside, the interiors of this film are also excellent. The well-appointed rooms of the big houses are grand in scale, but more interesting and more complex are the ramshackle spaces of the cavaliers’ “wing” and the various poor houses in which characters end up at various stages.

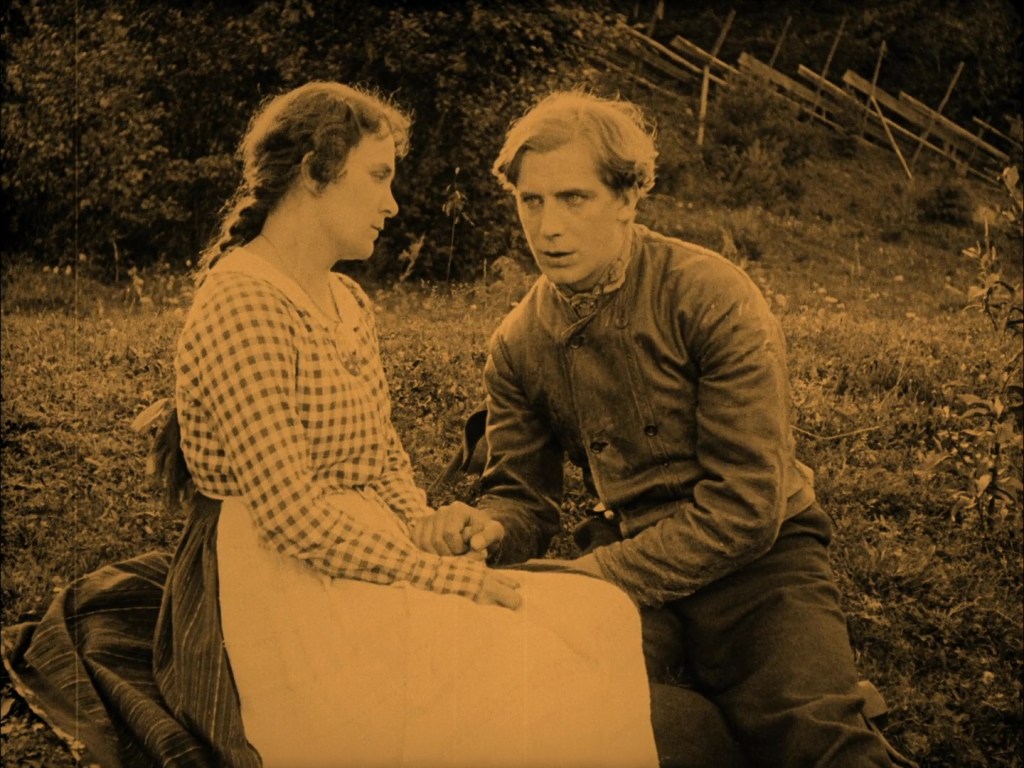

The cast of Gösta Berlings saga is led by Lars Hanson, who is superb in the title role. As well as being a strikingly handsome star, Hanson is an engaging and sympathetic screen presence – and Stiller knows just how to frame him, to light him, to capture his performance to its best. His character swings wildly from mood to mood, but Hanson can also be disarmingly reflective and vulnerable. It is these moments of stillness, often at the end of a sequence, that win you over to him. I must say that I find Hanson’s Don Juan-ish character in Sången om den eldröda blomman more comprehensible, and thus his highs and lows more moving than in Gösta Berlings saga. But Hanson is still striking on screen, and committed in his every scene of Gösta Berlings saga – whether channelling divine inspiration, drinking himself half to death, making promises he can’t keep, leaping into blazing buildings, or riding across frozen lakes. He has a lot to do and does it all with great aplomb.

Then there is Greta Garbo as Elizabeth, his Italian love interest and the not-quite-for-legal-reasons wife of the comic Henrik Dohna. I must be honest and say that I never really understood or engaged with Garbo’s character. This is partly an issue of performance, or of direction of performance. Stiller doesn’t quite know how to get the best out of Garbo, either in terms of her look or her gestures – and thus nor does Garbo. For me, Garbo is the least successful of the film’s major performances. But I think that the real issue is that her character is not well developed, and her relationship with Gösta a little unconvincing. We never see Elizabeth meeting Gösta for the first time, nor do we learn that he was tutoring her until later in the film, when we get a flashback to her Swedish lessons with him in the park. We see this same scene in flashback twice, but never the original scene or its context. I imagine this is a matter of missing material from the restoration, but if this is the case couldn’t we get a “missing scene” title to help explain? But even with this theoretical scene in place, I remain uncertain about the development of Elizabeth’s love for Gösta – and vice versa. Everything points to Gösta ending up with Marianne (they are attracted to each other, they clash, he rescues her from the snow, then from the fire), and Jenny Hasselqvist’s outstanding performance as Marianne makes her a far more appealing and comprehensible character than Elizabeth. Marianne’s smallpox aside (and are we to assume that a night out in the snow is the cause of this viral disease?), I was confused by the fact that she and Elizabeth are (so a title claims) good friends at the end of the film. This seems like a title doing a lot of work to fix quite a glaring dramatic tension, and to help us overcome any doubts about Marianne getting hard done by. The result of all this is that Garbo may look beautiful, but her character often doesn’t provide her with a clear and convincing set of motives or emotions to express or shape into a coherent performance. Don’t get me wrong, it’s still fascinating to see Garbo so young and not-quite-there-yet, but this is absolutely not her film.

For me, the real star is Gerda Lundequist as Margaretha Samzelius. When she has her first major scene with Gösta in the “wing” of the cavaliers, she suddenly brings a degree of emotional depth and complexity that the film has not yet plumbed. She narrates her past, puts his troubles in perspective, and sets up the personal trauma that comes back to haunt her later in the film. It’s a great scene, and she commands attention in everything she does. She is both naturalistic and expressive, superbly controlled without ever seeming mannered. What a great screen presence she is – you really can’t take your eyes of what she’s doing. This is the case even when the saga around her gets confusing. Dramatically, her relationship with the “cavaliers” that live on her estate goes through several total reversals of attitude that I find hard to comprehend. It’s an issue with the cavaliers more than with Margaretha, but she must bear the brunt of the dramatic topsy-turviness. Her most devoted cavalier (for reasons I don’t fully grasp) suddenly turns on the woman he has repeatedly said he loves, then feels devastated with guilt, then calls her an old witch, then (at the end of the film) feels remorseful once more. But whatever strange twists the film puts in the path of her character, Lundequist is there to embody the emotional resonance of the consequences. It’s a great performance.

Around the leads are a host of other strong, characterful performances. I have no reservations about any of the rest of the cast, but in discussing them I must work through some of my reservations about how the film knits together their various characters. For example, there is the scheming Märtha Dohna (played with relish by Ellen Hartman-Cederström). I can grasp her desire to disinherit her stepdaughter Ebba by (mis)allying her to Gösta: the film explains that this will enable Märtha’s natural son Henrik to inherit the Borg estate. But why at the end of the film does Märtha start taunting her prospective daughter-in-law, Elizabeth? Having tried so hard to get Elizabeth to sign the documents that would finalize the marriage, why does she suddenly turn on her and imply that the marriage would be a mistake? Seriously – why is she doing this? She also starts an argument with Gustafva Sinclaire about the history of her family and the identity of Henrik’s father. Given that the film has produced a dozen paintings (portraits of historic owners of Borg) to show on the walls of this very set, the faces of which are all clearly based on the features of the actor playing Henrik (Torsten Hammarén), we are given a clear visual answer (and a marvellous piece of design) – if no verbal answer in the dialogue of the scene. But this does not clarify the history of Märtha and her deceased(?) husband, nor the context of Henrik’s conception – nor the legal standing between the legitimate Ebba and the illegitimate(?) Henrik. God, what a confusing plotline – couldn’t the film make this clearer? Or at least not throw in last-second complications to make something relatively simple unnecessarily confusing?

I do not feel that I am merely nitpicking. It’s not unreasonable to want to know what is at stake in a drama and what motivates characters to act in the way that they do. For such a long and convoluted film, which has ample time to create complex narrative strands, I honestly don’t think Gösta Berlings saga is as coherent as it could be. At some point I will read the Lagerlöf novel, but my suspicion is that the film doesn’t go far enough in simplifying the original story. I often get the sense that far more has happened, and needs to be known, than I am being told in the film. Stiller creates a marvellously rich world on screen – but as impressive as the enormous sets and set-pieces are, I’m not wholly convinced in the coherence of the drama and its characters.

But I regret having to spend so much time on my reservations about this film. Despite all the above, I still think Gösta Berlings saga is tremendously pleasurable to watch – especially on a big screen with a full house and live music. In these circumstances, the film absolutely works. Indeed, one of the remarkable things about Gösta Berlings saga is that the way scenes can by be baggy or confusing yet somehow pack an emotional punch. Again and again, Stiller finds a way of pulling things together and providing you with a pay-off that works – even if the preceding material doesn’t.

In Act 2, the long flashback to Berling’s time as a priest is a case in point. The chapel scene, in which the hungover Gösta Berling delivers a knock-out sermon, doesn’t quite work on screen: intertitles have to do too much summarizing, to convey too much dramatic weight, to be convincing. (Stiller cannot quite find the cinematic means of expressing the content of the speech. Even Hanson’s performance, committed though it is, isn’t enough to substitute for what I presume is a lengthy chunk of prose in the novel.) Yet if the scene doesn’t quite come off, it is followed by a truly excellent realization of the aftermath of the sermon, as Gösta insults his parishioners and is run out of town. (We’ll pass over quite why he does this.) There follows a simply stunning image of him at night on a snowy, tree-lined road. It’s an image of amazing resonance, the very picture of dejection, isolation, loneliness, defeat. It’s beautiful to look at, with amazing low-level lighting, and expresses everything you need to know in a single shot. Perfect. Absolutely perfect. And it somehow redeems the rather uneven earlier part of the act. It gives you the emotional pay-off to what preceded it so effectively that the whole act makes more sense. This kind of thing happens many times across the film. Though I wasn’t convinced by Garbo as the main love interest, I was still moved when she got together with Gösta at the end. As I said, Stiller finds a way of ending things so effectively that your reservations (or at least mine) melt away.

Another factor must be mentioned, which is the terrific musical accompaniment by John Sweeney at the BFI screening. He kept up an amazing stream of lush, beautiful musical scenes and sequences that knitted together the drama into an effective whole. The race across the ice sequence in the penultimate act of the film, for example, was wonderfully handled. As elsewhere, I found the character motivation in this scene, and even the basic plotting, very confusing. (Dramatically, the whole sequence is oddly organized. Elizabeth heads off across the ice from Borg to Ekeby because she believes that her father will attack Gösta, but the audience has already been shown the father forgiving Gösta entirely. Fine – at least we know, even if it makes her journey less dramatically effective. But then why does Gösta seem to overtake Elizabeth rather than encounter her? The point of the scene is that they should meet each other coming from opposite directions, yet here he is catching up with her from behind. This isn’t just a matter of a different continuity pattern in Stiller’s editing, but a matter of dramatic staging. And when Gösta gives Elizabeth a lift, why does he steer away from Borg and admit that he is abducting her – not just from Borg but from Sweden? A fit of pique? Genuine passion? If so, from whence has it sprung? Only when Elizabeth asks him what the hell he’s doing does he mention the fact that they’re being chased by wolves. When did he realize this?) Yet during the screening, when Sweeney started pounding out a terrific refrain for the race across the ice, all these questions faded away: you’re left to marvel at the technical brilliance of the way the race is filmed, and the mad melodrama of it all. Even the faint sense of incoherence or (at least) incomprehension is somehow suspended, or transcended, in the thrill of such a gloriously cinematic scene. Later, when Ekeby has been rebuilt (but how?! and by what means?!), and Gösta and Elizabeth enter their new home, Sweeney’s grand, pealing chords were the perfect way to end the film. The final notes had hardly faded when the audience burst into applause: for the film, for the stars, for the music. Bravo!

I do hope this new restoration is released on DVD/Blu-ray, or at least made available online per other Swedish silents via the Svenska Filminstitut digital archive. Sadly, there is no guarantee that even the most important restorations ever get a commercial release. I still find it staggering that Sången om den eldröda blomman is not available on home media: you can buy the complete recording of Armas Järnefelt’s beautiful score on CD, but you cannot buy the film on DVD! Let’s hope something more happens to Gösta Berlings saga. I imagine that the old Matti Bye score will be expanded/reworked for any media release, but I do wish any original arrangement from 1924 would be investigated. Evidence of the music clearly survives, as Ann-Kristin Wallengren (in her thesis on music in Swedish silent film) mentions some of the cues used. (This included parts of Järnefelt’s score for Sången om den eldröda blomman, as well as of the Louis Silvers/William F. Peters score for Griffith’s Way Down East (1920).) It’s curious that the musical legacy of Swedish silent cinema has received so little attention, especially compared to the numerous original scores and arrangements that have been researched and restored for films elsewhere in Europe and in Hollywood.

Gösta Berlings saga is a big, baggy, beautiful film. I’m so glad I saw it in such wonderful circumstances at the BFI. And as much as I would welcome it on DVD/Blu-ray, I also cannot help think that I wouldn’t have been as moved – nor would my reservations have been so effectively overcome – if I had seen it on a small screen instead. Live cinema allows silent film to attain its maximum impact: audiences and music are an essential element of exhibition, and thus of understanding, that cannot be replicated at home. So if you ever get the chance to see Gösta Berlings saga this way, seize it!

Paul Cuff