This week, I revisit some of the cinematic afterlives of Nosferatu – Eine Symphonie des Grauens (1922; Ger.; F.W. Murnau). After catching Robert Eggers’s remake of the film earlier this year, I discussed my thoughts on its relation to the silent original in a podcast with Jose Arroyo (freely available here). To prepare for this, I rewatched (and watched for the first time) several modern films that cite or rework Murnau’s original – and made notes on my thoughts as I went. As a kind of written addendum to the podcast, I have collated and attempted to polish these thoughts into what follows…

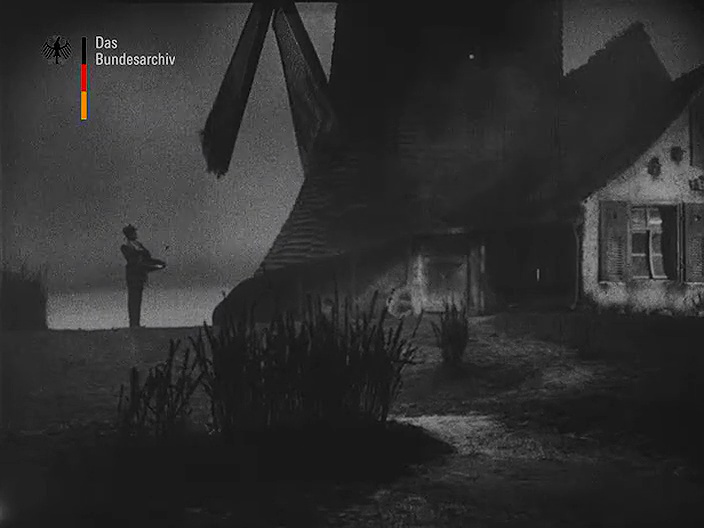

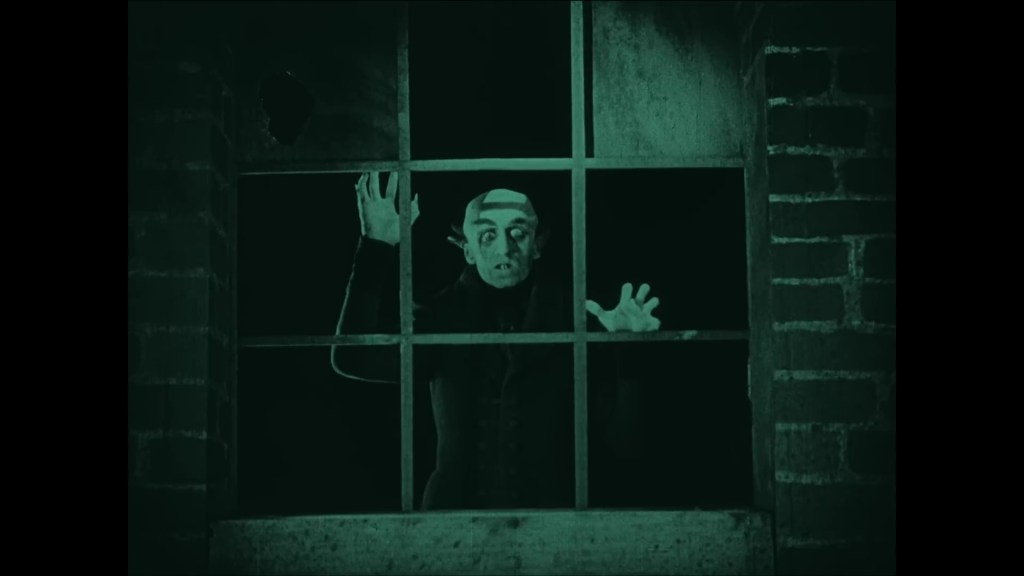

Nosferatu – Eine Symphonie des Grauens (1922; Ger.; F.W. Murnau). What can I say about this wonderfully strange and compelling film? Every image is perfectly composed, marvellously controlled. The world on screen, enriched by tinting, has marvellous texture and resonance. Nosferatu is a fantasy and a period piece, but both the fantasy and the period are rooted in real places – and, for me, its exteriors truly make the film. The town, the forest, the mountains, the castle, and the coast – these locations have such a sense of pastness, and such pictorial power, that they sink into your memory. No amount of parody or pastiche can lessen their value. So too with the performers. They are cinematic archetypes, enacting some kind ritual drama that future generations feel obliged to mimic. But the performances are also playful and delightful, even their most naïve gestures somehow innocent of cliché. There is more than a touch of camp about Max Schreck’s Nosferatu, but a camp that is always sinister. His sexual predation is not quite human; interpreting his desires and motives is like trying to understand the consciousness of an animal or an insect; those piercing eyes are bright with a life than cannot be fathomed. Murnau shapes Nosferatu’s otherworldliness through the darkness from which he emerges, the shadows he casts, the untenanted spaces he inhabits. The film plays with his ability to move across space and time: he walks with the ancient deliberation of an old aristocrat in one scene then scuttles at terrifying speed in another. The figure is allied with cinema’s own uncanniness, the medium enabling the monster: his carriage hurtling through a forest like a berserk toy, his erect body rising in magical defiance of gravity from his coffin. All this richness of image and gesture is enhanced by Hans Erdmann’s original score, best heard (I’ll have you know) via Gillian B. Anderson’s edition rather than the version released on various DVD/Blu-rays. (Anderson’s edition more closely replicates Erdmann’s original orchestration but remains, sadly, available only on a long out-of-print CD.) As it shifts from sequence to sequence, Erdmann’s music moves from the lyrical to the rustic and the elemental; it is charming, brooding, devastatingly simple. As its title states boldly at the outset, Nosferatu is a symphony of horror – a truly complete work of cinematic and musical art. As much as its images and ideas have been treated as a grab bag for future generations to ransack, it still holds an un-replicable splendour.

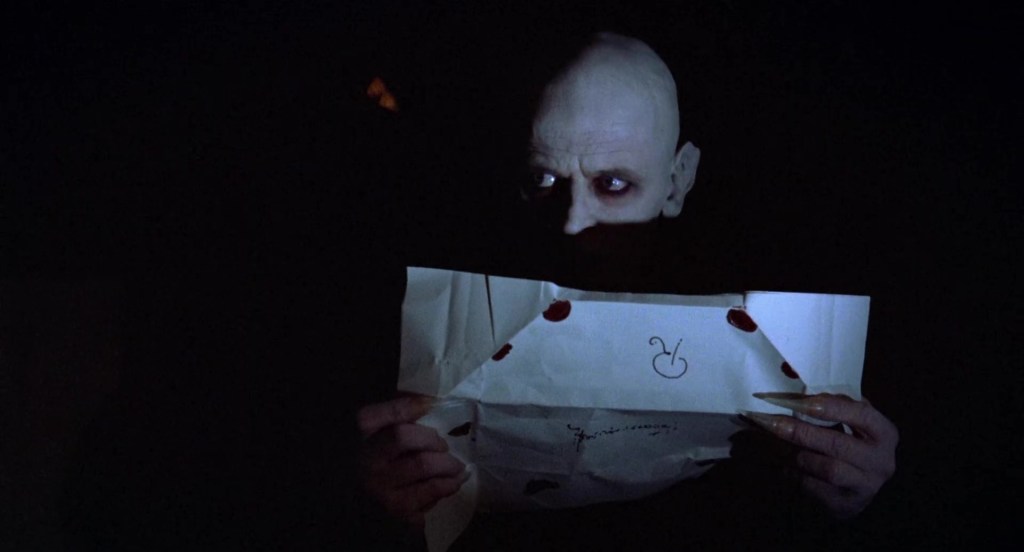

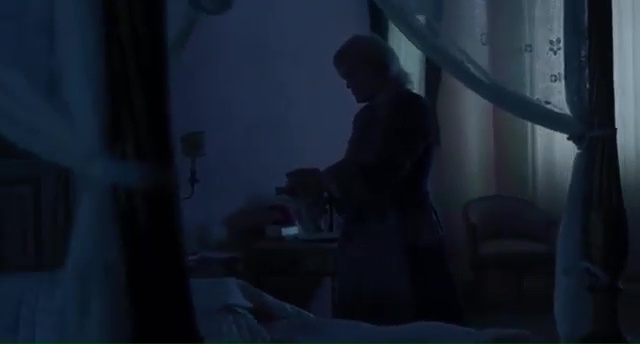

Nosferatu: Phantom der Nacht (1979; W. Ger./Fr.; Werner Herzog). The first full remake of Murnau’s film, and by far the best. Shot on location in the Netherlands and Czechoslovakia, Herzog has an unerring knack for the right places, filmed at the right time of day, captured in the right conditions. Always in his films, you can see that this is a director who has spent time walking. These aren’t pretty landscapes, touristic ones, places chosen second- or third-hand – they are fresh, harsh, rugged, sublime. There is also the sense that Herzog’s minimal budget and no-frills filmmaking benefits the atmosphere: it always feels like he has snuck into these spaces without asking permission. These are stolen images, not forged ones. The town, the coast, the mountains, the castle – all become otherworldly, other-timely. The camera seems to have found out odd corners of Europe where the past lives on, like finding patches of frost on a bright spring morning. The supernatural seems almost an extension of this natural world, the hypnotic slow-motion images of bats, the time-lapse photography of moving clouds, or the opening footage of mummified corpses fit perfectly into this world, this mood – all are implacably real and ungraspably strange. The cast, too, fits in with this mood – through costumes and setting and lighting, yes, but through performance. All is mood. This Nosferatu is ridden by angst, pain. Herzog often said that Klaus Kinski’s best performances came when he was exhausted to the point of collapse. The actor would rant and rage and scream and shout and threaten murder, and Herzog would wait until the storm ebbed – then he would roll the camera and shoot the scene. The result is an air of timeless exhaustion, of a pitiable figure advancing through centuries of fatigue. The slowness of Kinski’s gestures across the film are dreamlike, but then he moves with terrifying speed when his instincts are riled – as when he sees blood on Harker’s hand, or in his writhing death-throes, curling up like he’s a sheet of parchment caught in a flame. It’s a performance of amazing power that draws you in every time you watch it. Just as fine, perhaps finer still, is Isabelle Adjani. She is as otherworldly and magnetic as any of Herzog’s images, who indeed seems to have imbibed and embodied them. Her glance, her movement, her posture – what a sublime presence she is on screen. (Yes, I really do prefer Adjani to Greta Schröder in Murnau’s film.) Elsewhere, Herzog brings surprising depth and pathos to his characters. As Renfield, Roland Topor is oddly and touchingly gentle – a sad figure, a lonely man chasing someone to love him, or a child chasing a father. He is a world away from the comically sinister Alexander Granach as Knock in Murnau’s film (or the later scenery-chewing performances of subsequent versions). And I do love Bruno Ganz’s honest, harried Harker. He does not have the boyish innocence of Gustav von Wangenheim for Murnau, but I can believe him as a man who lives in this particular world, who loves his wife, who finds himself in thrall to the uncanny. His slow transformation into a vampire across the film is marvellous, and I have always loved his final scene. He has a marvellously comic flourish (getting the maid to sweep away the salt that keeps him magically penned in a corner of the living room), as though he were touched not merely by the spirit of Kinski but by the spirit of Max Schreck. Then Ganz takes on the faraway look of someone being drawn into another kind of life, or afterlife. The last image of him on horseback, riding across the wind-whipped sands, accompanied by the “Sanctus” from Gounod’s mass, is beautiful. This is a film of which I remain inordinately fond.

Vampires in Venice [aka Nosferatu in Venice] (1988; It.; Augusto Caminito/Klaus Kinski). Yes, dear reader, I even watched this – just for you. Frankly, it was hardly worth it for the few sentences I write here. Kinski has grown his hair, a caged lion with a rockstar mane. He wanders with glazed, angry boredom around Venice – in a Venice pretending vainly to be the past. Christopher Plummer tries to track him down in the present, encountering the vapid stock characters of post-synchronized Euro-horror. It’s a slovenly, sloppy film – salacious yet soporific. I drifted in and out of its louche, morbid pall of atmosphere. I remember the final images, which touch on the poetic – yet somehow remain earthbound. Kinski, a naked woman in his arms, walking across a deserted square in the fog. Where was the film that justified such an image? Murnau is dead, and director Caminito (and Kinski, his eminence grise) did not wander into the past to find him, or to resurrect anything of his world.

Shadow of the Vampire (2000; US/UK/Lu.; E. Elias Merhige). A film about the shooting of Murnau’s film, the concept of which is that the director hired a real vampire for the role of Nosferatu. What a curious thing this is. The concept is neat enough, but it is framed in such odd terms – at least, from a film historian’s perspective. We are told (via an intertitle, no less) that Murnau creates “the most realistic vampire film ever made” – and the character later explains that realism is the essence of cinema. For the film, this is fine, but I wonder if this is how the writer and director of Shadow of the Vampire really felt about Murnau. Does anyone associate Murnau with “realism”, let alone define him by this term? I ask, because in all other senses Shadow of the Vampire is oddly loyal to Murnau – recreating with rather charming precision many of his original shots. We see the camera’s eye view of scenes, though these shots mimic the worn monochrome quality of old celluloid. Yet the film also shows us Schreck watching some of the landscapes from Nosferatu projected on a screen – but instead of pristine rushes, we get the battered and blasted tones of a grotty 16mm print. Amid the attention to period detail, this one glimpse of Murnau’s original footage is distinctly unflattering. John Malkovich is (inevitably) a weirdly compelling Murnau, obsessive and cunning but often charming. Willem Dafoe has a twinkle in his eye as Max Schreck, knowing that it’s all a game – even if the film takes itself a little too seriously. Indeed, my reservations about Shadow of the Vampire all stem from the way it addresses its own premise. The film gestures towards an ideology or aesthetic of realism but never develops it, nor does it allow the horror to grow frightening enough to compensate. Shadow of the Vampire is not a comedy, but the comedic shadows its every move. Dafoe, I think, knows always the dramatic limitations of these projects. He is never parodic in drama, but he can tread the line wonderfully well, as he does in Eggers’s Nosferatu. Shadow of the Vampire is interesting enough as an idea, and as a curious period drama, but I’m not sure it is anything more than a superficial engagement with the cinematic past.

Dracula: Pages from a Virgin’s Diary (2002; Can.; Guy Maddin). I sometimes get asked what I think of Guy Maddin, or else people assume that I am interested in his “new” silent films. I confess that I have never taken much interest in them at all, nor have I ever felt strong kinship or interest in any “new” silent productions. I was once in Paris at the time of a retrospective and caught Maddin in person, introducing Tales from the Gimli Hospital (1988). It remains the only film of his I have seen in the cinema, and I confess I found it interminable. Maddin certainly captures the stultifying awkwardness of certain early sound productions, but it felt like a short film blown out to feature proportions and even at 70 minutes it was a slog to sit through. His Dracula: Pages from a Virgin’s Diary is a much more lavish affair, taking its cue from innumerable previous iterations of the vampire myth – but shot silently and synchronized to a music soundtrack. In many ways, it’s a superb production. Maddin lights and shoots his scenes with stylish brilliance. His staging and choreography are striking, just as his mobile camera and his editing are dashing and spirited. But I regret how the many parodic performances and gestures it makes (not to mention the garish yellow text for the intertitles that sits superimposed over monochrome imagery) keep me at a distance. Campness need not be so superficial nor so silly as it is here, and these qualities make its aesthetic sumptuousness seem no more than surface and gesture. It has the trappings of silence but not of its depth or uncanniness. It’s a filmed ballet, but one without any frisson of liveness or great physicality. Rather, it’s a danced film – and I swiftly bored of its pretty artifices. Maddin’s film is only a very distant relation to Murnau, and despite its beautiful (sometimes ravishing) moments it has no resonance.

Nosferatu: A Symphony of Horror (2023; US; David Lee Fisher). You may not have noticed the release of this film, but I did – and its very existence requires some contextual explanation. Fisher’s only other film is The Cabinet of Dr Caligari (2005), a remake of Robert Wiene’s silent original. Using digital scans of the original film, Fisher recreates (not quite shot-for-shot) the aesthetic with a new cast – and dialogue. I had the peculiar privilege of encountering this film for the first time on a big screen with a class of film history students, after having watched Wiene’s original the previous week. I am always very sensitive to the mood of a room, especially of students – I do so want them to engage with (if not love) the films they are shown. There was nothing worse as a lecturer to feel that you were showing students something they actively hated (and I could always feel it in the room). But Fisher’s Caligari was the first time I felt glad to sense that the room had turned against a film. As bad a habit as it is for a critic to feel superior to a film, it is a worse habit for the director of a remake to feel equal to the original. The digital process of copy-and-pasting sets is neat enough, but the film has no idea how to replicate the sense of presence: Fisher’s cast are walking about mostly in green screen spaces, utterly divorced from their surroundings. It has the trappings of a period piece, but neither costumes nor faces nor performances can convince they have anything to do with the period. The dialogue is absurd, banal to the point of existential embarrassment. (How can such a script be thought adequate?) And when Fisher recreates the famous close-up of Conrad Veidt’s Caligari opening his eyes, the void between past and present is at its most unbridgeable, the gulf in intensity of drama and performance most apparent. (It is the same problem that Scorsese had in including this same shot of Veidt in Hugo (2011): it has infinitely more power and presence than anything in the surrounding film.)

So to Fisher’s second film… Nosferatu: A Symphony of Horror was, so the internet tells me, funded via a Kickstarter campaign way back in the 2010s. The film was purportedly shot in 2015-16, which seems remarkable given that it took another seven years to get released. Of course, it has been released only for streaming via Amazon Prime, which I suppose is the equivalent nowadays of what was once called “straight to video”. As with Fisher’s Caligari, original images from Murnau’s film have been digitally transplanted around a new cast. The effect is both more detailed and somehow more disappointing. In Fisher’s Caligari, the sets are at least flat in the original. In Nosferatu, an entire world is reprocessed in a manner that I found positively sickly. I earlier described the richness of the locations being one of the chief pleasures of Murnau’s film, and their systematic eradication was one of the chief disappointments of Fisher’s film. The landscapes are CGI creations, imaginatively stunted – as is every interior space, every shot in fact. The backdrop to every scene resembles a generic screensaver, without a trace of weight or reality or mystery. (The costumes are no less convincing, nor even the occasional moustache.) Among the cast, I single out Sarah Carter as the only figure to have genuine emotional depth – or any kind of convincing presence. She stands in a different league to anyone else on screen, even Doug Jones, whose Orlok is at least a committed performance. But it, like everything else in the film, is an exhausted stereotype of something we’ve seen dozens of times before. Fisher’s technology has improved, but he still cannot write dialogue or assemble convincing faces or performances. In comparison, Maddin’s Dracula (for all my reservations) is an infinitely more convincing use of a silent milieu.

Nosferatu (2024; US; Robert Eggers). All of which brings us to Eggers. Oh, Eggers… I have only seen one of his other films, and I thought The Lighthouse (2019) was as dramatically hollow as it was stylistically skilled. The tone of the script and performances rubbed me the wrong way. Was this a parody that took itself far too seriously, or a serious drama that was incredibly flippant? Much as I admired the way it looked, I squirmed with embarrassment and irritation at the dramatic tone. Some of my reservations about The Lighthouse I also have about Nosferatu, but I enjoyed the latter much more.

For a start, it looks lavish, and Eggers knows how to dress a set and provide a beautiful background. There are images that evoke Caspar David Friedrich (almost more so than evocations of Murnau), and there are glimpses of some fabulous locations (in the Czech Republic). The whole section in which Hutter travels to the east is the best in the film, and I wish I had seen more of the amazing churches and villages glimpsed all-too-briefly here.

But the richness of this part of the film’s world, so breezily skipped through, makes the inadequacies of the Wisburg setting more apparent. The exterior spaces of Wisburg consist of little more than two streets and a very small crowd of inhabitants. There is no sense of place and time here, nor of the scale of the invasion of the rats and the accompanying plague. (Compare this to Herzog’s film to see how much difference this space makes in dramatic tone and mood.) And while I loved some of the scenes set on the coast, you never get the sense that Eggers quite knows how to let these images sink in or resonate. They are very pretty, but they have no greater purpose. Eggers can dress a world impeccably, but a world is also people and ideas – these take work of a subtler and more difficult kind. As with The Lighthouse, to me Nosferatu was a very modern set of people dressing up and playing the past. The very impeccability of the images made the dialogue and the tone of many performances incongruous. While the film is happy to employ religion and supernaturalism, no-one seems to believe in any kind of corresponding or supporting ideology. And while the film offers a token critique of (male) medical authority, it is also entirely predicated on the idea of female desire as hysterical and “other”. (Nosferatu is explicitly summoned, if not created, by Ellen.) What, if anything, does this film believe, or want us to believe, about the drama it shows?

The performances are a curious mix. I must begin by praising Nicholas Hoult, who as Thomas Hutter is the emotional heart of Nosferatu. I was moved by him as by nothing else in the film. When he says he loves Ellen, you truly believe it – a conviction without which the film would fall down. Hoult was absolutely the best thing in Nosferatu, the least histrionic and the most believable. Bill Skarsgård’s Nosferatu is very… well, loud. His abstract presence is first signalled by a vast roar of sound in the film’s prologue that had me covering my ears. And when we meet him and he speaks, his voice (featuring rrrs that roll like no other), even in a whisper, reverberates throughout the speakers and floor of the cinema. Utterly unlike the silent and unknowable figure of Murnau’s film, this Nosferatu is a physical, corporeal, rotting being, defined as much by sound as image.

As Ellen, I found Lily-Rose Depp oddly unsatisfying. She gets to romp and roar and moan and writhe, and does so with aplomb. (Many of her poses are supposedly based on historical accounts of madness/hysteria, but I felt I had seen young women writhe and vomit blood this way a thousand times before in horror films.) But when she must deliver the (vaguely) period dialogue, it carries the whiff of parody. In part, it is the script’s fault for attempting (and, I think, failing) to mimic nineteenth-century turns of phrase, but mainly it is an issue of tone. I remain unconvinced that Eggers knows how to handle (or to decide upon) a consistent or convincing tone. Depp was one of the main reasons I felt this Nosferatu was playing dress-up. Again, I do not blame the performer so much as the director. This too is the case with Aaron Taylor-Johnson’s performance as Harding, which I found inexplicably bad. How can an English actor speak English so unconvincingly? I do not blame Taylor-Johnson, for he’s clearly been asked to perform like this by the director. But why? Why is he so artificial, so mannered, so parodically out of place? I am at a loss as to how I am supposed to feel towards Harding or his family. His children are ghastly screaming creatures, mobilized by the film (so I thought while watching the first half) to make us glad of their eventual demise – but when the demise came, suddenly the tone suggested they had earned our sympathy, as had Harding. Why? How? When? As for Simon McBurney’s Knock, he is as scenery-chewing as they come, gnawing on live animals and shouting – always shouting. While the characterization might echo Murnau’s version, it brings nothing new (other than fatuous gore). Just think how tender Herzog’s Renfield is by comparison, a character who is more than one-dimensional – and whose madness is a blissfully quiet delight.

What of Eggers’s relationship to Murnau? I noticed how the new film’s credits never mention Murnau, only Henrik Galeen, the screenwriter of the 1922 film. How odd, and how ungenerous, given the direct citation of the film’s (i.e. Murnau’s) imagery as well as its characters. Yet I never quite got the sense that film history truly informed this film. Eggers has surely seen Carl-Th. Dryer’s Vampyr (1932) – the floating shadows, the uncertainty of space, the dislocation of sound and image – but his Nosferatu has nothing uncanny about it. Dryer makes his sounds teeter on silence, slip back into it, emerge unsettlingly from it; Eggers makes his film quite unbelievably loud, roaring, throbbing – even his vampire’s whispers are rendered at the volume of earthquakes. Nor did I get a sense of other Galeen films lurking in the background of Eggers’s. Perhaps this new Nosferatu has some faint echo of Galeen’s Alraune (1928), but only in the sense that both films have an interest in female sexuality and the uncanny. (And let me be absolutely clear: Lily-Rose Depp is no Brigitte Helm.) But I found no echo of the world of Galeen’s Der Student von Prag (1926), which has its own rich cultural history, being itself a remake of the (to my mind) superior version of 1913 (a film I discussed here). This is a whole strain of German cinema that I feel very little evidence of in Eggers’s film. On its own terms, this new Nosferatu is a perfectly enjoyable film – but it is a bold move to identify itself with the silent past. If nothing else, it invites comparison where otherwise it might not. Having summoned the comparison, I cannot but think that Murnau’s film is an eternally peculiar and resonant work whose secrets elude Eggers.

In summary… well, what is my summation? I set out on this little crash course through the afterlives of Nosferatu with the aim of suggesting how and where Murnau’s film inspired future generations. In the end, I fear that all I’ve done is complain. If this does not make for a neutral survey, at least it’s an honest assessment of what I felt. The more remakes, revisits, or (god help us) “reimaginings” of a film, the wearier I grow. There is something in the metaphor of the vampire, in its unkillable afterlife, that fits the ceaseless round of resurrections cinema has performed on Nosferatu. But having rewatched all these films, I feel I am become Kinski’s incarnation – eternally weary, wishing for the end of this eternal round. Let me return to my silent realm.

Paul Cuff