It’s the final day of streaming, and with two feature films to cover I’ve decided to dedicate a post to each one. First up is a film which bowled me over completely, and about which I will gush unapologetically…

The Lady (1925; US; Frank Borzage)

Working-class music hall singer Polly Pearl marries a wastrel aristocrat who abandons her on their honeymoon in Monte Carlo, leaving her alone and pregnant. When the husband dies, Polly’s former father-in-law arrives to claim custody of the child, but she sends the boy away with a foster family, knowing that she may never see him again…

We’re back in the company of Norma Talmadge, in a film directed by the great Frank Borzage and a script by Frances Marion. “The Lady” is an aspirational title that bar manager Polly had always hoped to attain. The title introducing “the Lady” makes way for a close-up of a woman’s hands wiping beer and froth from a bar. The transition lays bare the conflict between hopes and reality at the heart of Polly’s life.

British soldiers stumble into Polly’s “English bar”. The sergeant is drunk, his comrade sober. The drunk petulantly squirts Polly with a soda siphon. “That’s a ‘ell of a way to treat a lady!” she says. There’s laughter from the clientele: “Can you imagine Polly Pearl callin’ herself a lady!” It’s a cheery introduction, but a hurtful one. The laughter is friendly, but we know what kind of life she must have led. It’s a nice detail in the film’s titles that the word “lady” is often on the last line, or is even the last word, of the text: the tail of the “y” is elongated in the same way as the first “y” of the first “lady” in the introduction.

A kindly face on another table. Mr Wendover was born in the same town. Polly hasn’t been home for fifteen years. The close-ups of Talmadge are beautiful. Her grey hair forms part of her gentle back-lit halo. Wendover calls her “Madame Polly”. He shows her photos of their lost far-off hometown. A montage of preserved glimpses of home. There is a lengthy close-up of Talmadge with tears in her eyes. It’s an extraordinary intimacy between the camera and her face. She once “dreamed of being a lady”. Wendover sees her emotion. “You must have had an interesting life. Tell me about it, won’t you, Madame Polly?” he asks. It’s a mark of his respect that the “y” of the “you” and “Polly” have the elongated tails of “lady”.

Twenty-four years earlier, in London. Here is Polly frolicking on stage, a different person entirely—her body, her face transformed, filled with energy and life. From a box at the side of the stage, Leonard St Aubyns gazes at her in rapture.

Music hall life is brought to the screen with a dozen lovely comic touches. Look at the boy who stands on guard at the stage door, letting in no-one—until he’s bribed with a cigar by a flash dresser. The man even lights it for the boy, who stands there puffing contentedly.

Polly’s friend Fanny makes insinuations about her relationship with St Aubyns. She makes a fuss over the roses he gave her. “Can’t you see diamond lizards in his eyes?” Fanny asks, gesturing to her own spangle on her dress. Polly says she can’t pay, Fanny says she’s “too afraid to pay for it”—and she means paying with her body. “Some day I hopes to be nice”, Polly replies, and Fanny laughs at her desire to be “a lady”.

The flash dresser is Tom Robinson, a bookmaker who comes with flowers for Polly but makes do with Fanny. He looks the latter over. “Oh well”, he says “—seein’ as how the outfit’s paid for—” and off they go. It’s a funny, sad series of exchanges, and it’s strangely moving when all the other characters have gone and it’s just Polly and St Aubyns alone backstage. There’s no title here, but you can read her lips—“I love you”—and see that he does not return her words before they kiss.

(Outside, Fanny asks Tom: “Sorry it’s me not Polly?” He pauses, then says: “I’ll tell you after the ride.” It’s a great line, but it also undercuts the sentiment of the surrounding scene—and we’ll see that this couple’s kind of honesty is perhaps more long-lasting than other relationships in the film.)

The stern father of St Aubyns arrives and offers to pay Polly to send his son away. Immediately he tries to put a price on her, the most devaluing thing of all. For he’s convinced his son is wasting all his money on her, something she fiercely denies. Polly shows him the marriage ring, which she keeps hidden in her blouse. “Not another penny until you return home—alone”, the father says to his son. What is Leonard’s reaction? He sits sulking on a chair. It’s hurtful that his first thought is for money, not for Polly. And it’s moving how optimistic Polly is, saying she’d love him all the same if he were poor. And Leonard rashly announces a honeymoon to Monte Carlo, which makes her cry for happiness.

The last sight of the London world: the theatre boy stumbles in, sucking on the remains of the cigar. We see the world through his befogged eyes: everyone is distorted and squished. It’s a comic touch, but it’s also strangely sinister.

For now we’re in Monte Carlo and already Polly’s life is unravelling. Leonard is gambling and losing, and flirting with a well-dressed woman called Adrienne. Polly laughs at the woman’s pretensions, but Fanny and Tom (still together) warn her she’s after her husband. Leonard is kissing Adrienne’s hand and gets irritated when Polly approaches. She tries to be friendly with Adrienne but the latter snubs her.

It’s at this point that the print begins to disintegrate before our eyes, just as Polly’s relationship disintegrates. We see fragments, glimpses of Polly’s heartbreak. Leonard “can’t stand the riffraff you associate with”. But Tom and Fanny prove their worth, comforting Polly who now has the courage to confront Leonard in the hotel. Polly finds him locked in an embrace with Adrienne. The latter remains cool and smokes instead of replying to Polly’s questions. Infuriated, Polly hurls herself at Adrienne. Her violence is less damaging than what Leonard says next: “You common little trollop! … My father was right! I was a fool to marry a guttersnipe like you!” And there is that elongated “y” in the last word of the text, its long tail grimly echoing the “y” of “lady”. (It’s such a clever little visual trope to use, this simple “y”—and every time it calls us back to the main title and the idea it summons.) Polly stands there, hope draining from her body—as the film warps and bleaches around her.

Marseille, months later. Polly stumbles through dark streets into a tavern. She sits and asks for tea, to the shock of the waiter and owner. Madame Blanche sees Polly’s vulnerable state and pounces, black arms gleaming with sequins, holding her neck and pouring alcohol into her. Polly realizes what kind of place it is: drunks, sailors and women intermingle. She flees in fear but collapses outside and is carried back in.

There is a cut to an astonishing reveal: Polly is in bed, playing with an infant’s foot, the rest of the baby concealed under the sheet. Its tiny fingers wrapped around her thumb. But in comes Mme Blanche. “You pauper, lyin’ in bed like a lady!” Mme demands Polly dance and sing for her customers to earn a living. (The censor would clearly not allow Polly to become a prostitute, but it’s the closest the film can get.)

So Polly is on stage, melting hearts. She refuses money from a customer of another kind. Mme is angry that Polly only smiles for her “brat” and not for her customers. But the baby clutches at Mme’s fingers and her heart softens a little.

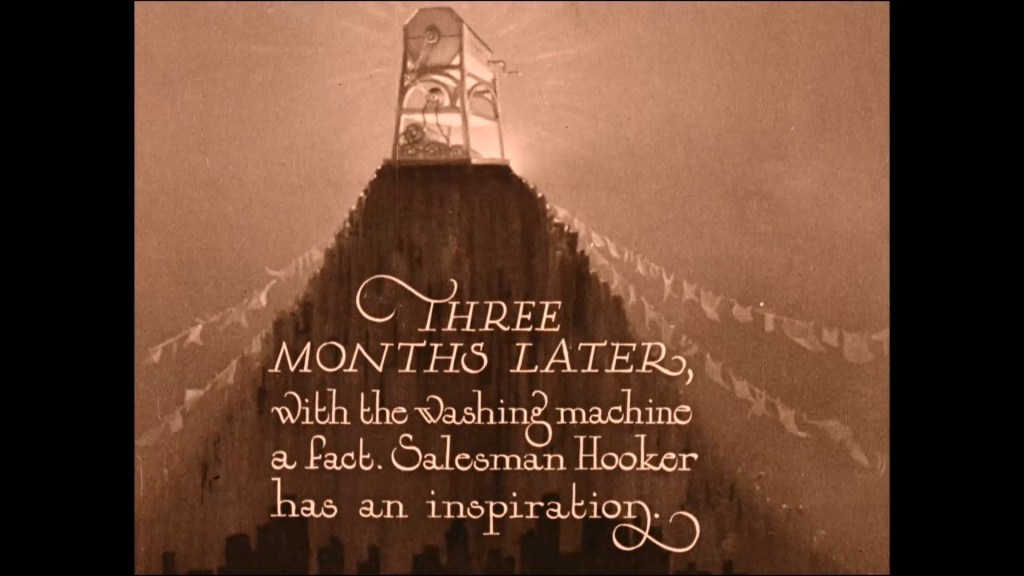

Just as Polly is settling into some kind of safe existence, an agent sent by the elder St Aubyns arrives and writes to London that he has found “the grandson”.

Rev. Cairns, an English man of the cloth, baptizes the child: the boy is called Leonard. Is it her way of recapturing the past? Or reclaiming the future? A boy that might grow up to be better than his father. A moment of solemnity in the tavern/brothel when Cairns quotes the line “and lead us not into temptation but deliver us from evil”. One of the girls laughs, another has tears in her eyes.

St Aubyns arrives. Polly sees him and realizes why he’s come: we see all her thoughts in her face. St Aubyns announces that Leonard is dead and that he has come with a court order of custody “on the grounds that you are unfit”. (Again, the “y” of “you” is the elongated “y” of “lady”.) We can read her lips: “You hypocrite”, she cries, as he gestures with contempt at the world he sees around him. She must fetch the child. She paces the room, going back and forth from cot to door, turning in indecision. “He’ll ruin him like he did Leonard”, she says, and begs Mrs Cairns to take the child away with her—to somewhere where even Polly can’t trace them.

(Cut back to a woman trawling for clients in the tavern. She tries St Aubyns and his agent, but is treated with stuffy contempt: so she sticks her tongue out at them and knocks the old man’s hat over his nose. It’s the kind of reaction we all want to give St Aubyns.)

Polly issues her last hopes to Mrs Cairns: “give him your name and bring him up like your own—a gentleman.” She kisses her son goodbye. “Promise me you’ll be to him all that I hoped to be.” Finally: “Don’t let him know that his mother—wasn’t a lady.” It’s a devastating little moment. And when Polly runs back to the tavern, we see everything on her face: grief, shaken into triumphant defiance as she thinks of outwitting St Aubyns. She says she’ll sing whilst they’re waiting. As Mme Blanche and Mrs Cairns prepare for the child’s departure, we see Polly sing: the desperation of her performance, as she tries to hold back her fear while singing. When she knows the child is safe, she is laughing and crying and almost insensible as confronts St Aubyns: “damn you” she says, and strikes him just as she struck at Leonard’s lover. She collapses.

And when we see her again, five years later, it’s as if she has hardly been able to pick herself up from the ground. Here she is, searching the streets of London for her child. Talmadge breaks my heart as this older character. Her face has become older; it’s not disguised, it’s all in the performance. Her face has become less mobile, slower to reveal its expressions. The emotion is held in the eyes. Her restraint is so touching. And the lighting, the dark streets, the faint wash of violent tinting—it’s a perfectly, perfectly sad scene. Polly is selling flowers. A child stops and talks to her. She asks him his name. An angry father moves him on. Polly and her soggy little garlands are moved on by the police.

Tom and Fanny appear, in a car. They are still together, all these years later. Polly tries to sell them a flower. She flees in shame, then changes her mind and calls out after they are gone. Truly, Talmadge is glorious. Look at her face in the long close-up after the car has gone; a whole series of emotions and exhaustion, and Borzage lets it all play out before he cuts to a wider shot. Another child and mother appear. “What might your name be, me lad?” Before he can answer, the film deteriorates again. She still waits to find Leonard. A passing policeman says: “If I was you, I’d give up waiting for that young man” and pats her on the shoulder. He leaves, and there is another extended moment at the end of a scene when it’s just Talmadge on screen. These in-between moments, when action is left behind, are made to tell.

We are back to the present, in Polly’s English bar in Marseille. “Life’s done for me, but some’ow I go on—and on—” she says. Acts of kindness have kept her going. Mme Blanche died and left her money, which enabled her to buy this bar.

But here is an act of selfishness. A brawl erupts, the British sergeant drawing a pistol. His comrade grabs it but is punched away, accidentally firing as he falls back into Polly’s arms. The sergeant is dead. The police arrive.

And, yes, the young man in Polly’s arms is her son. You realize it instinctively, even before she sees his soldier’s identification tag: “Leonard Cairns”. He’s unconscious, asleep like a child in her arms. Talmadge has another extraordinary solo performance in medium close-up. She looks again at the name tag. She can hardly believe it, as we might not. The film plants this miracle at her feet, at our feet—and all at once she realizes what has happened, that he has killed a man, that she might lose him again. “He’s my boy!” she cries to Mr Wendover, and somehow not hearing her words at this point is enormously moving. (Why is that so? There’s always a distance between us and these silent figures. The best silent films invite us to cross this threshold, and when this happens there’s a kind of connection made all the deeper for the time and space it traverses. So yes, we can read Norma Talmadge’s lips—mouthing the rediscovery of her lost son, nearly a hundred years ago—and discover her words again, spoken inside our own heads.)

Already the police are here. Leonard is alive, struggling to open his eyes. When he recalls the fight, he grieves the death of his friend: “we were buddies”, he carried him across No Man’s land. Another region of grief and loss opens up. Polly tries to convince Leonard that she fired the lethal shot: “You know, my lad, that I shot him. It means nothing to me—you’re so young—and need your chance.” (Yes, an elongated “y”, linking his chance with her longing for a different life.) Leonard looks at her with wonder, and they are eye to eye. Polly asks Mr Wendover to back-up her claim—she is staring at him, desperate to give her boy a chance. But Leonard refuses to let her take the blame: “There are some things a gentlemen cannot do.” And Mrs Cairns’s promise to her is fulfilled—another emotional payoff in this astonishing scene.

“But it’s the most wonderful thing I ever heard of—”, Leonard says, that Polly should try to save him, a stranger. “But you’re not a stranger—why—I—” (she pauses, and it’s agony!) “—I have a wonderful memory of a son like you”, she goes on, and a tear falls from her cheek—the most perfect moment, in this most perfect scene. Even the “y” of “you” links him to her, which is matched in his response: “And I have a memory of a wonderful mother like you”. She puts her hand upon his cheek. It’s not quite a caress, it doesn’t dare to be. But when he turns to leave, she asks him: “Do you mind if I kiss you—in memory of my boy?” They embrace, and it’s a kind of fulfilment of the miracle.

He marches out of her life, escorted by the police. Her hand wipes the bar, as in the opening shot. And I didn’t think the film could pull any more emotional punches, but somehow it does. Mr Wendover says he won’t leave France until Leonard is freed. Polly is thankful her son is a gentleman. “And do you know why he is a gentleman?” Mr Wendover asks. “Because his mother happens to be—” (her hand stops wiping the bar) “—a Lady.” She looks up at him. And there is her face, her face that has carried the whole film, smiling at the realization that she may be loved. It’s another perfect moment, in a film full of perfect moments. Dissolve. The End.

The Lady will be one of those films that I won’t be able to describe to someone else without welling up. (This happens with a few other silents. I remember giving a lecture at the London Film School and almost breaking down mid-sentence when I tried to describe the ending of Sjöström’s Ingeborg Holm [1913]. I wasn’t expecting it, but there it came, the wave of emotion, and my voice cut out in front of a roomful of strangers.) Talmadge is of course the star and holds the film’s huge emotional weight, but the whole thing is wonderful. The cast are uniformly excellent, the script has a wonderful balance of the tragic, the comic, and the miraculous. It sets things up that you don’t immediately spot, then knocks you over with them at the end. And despite the damage at various points, the print is absolutely beautiful to look at. The lighting is superb, the sets are atmospheric, and all united with the gorgeous tinting that brings warmth and texture to the world on screen. I’ll be thinking about this film for years to come, and no doubt still blubbing when trying to describe it to strangers. Many thanks for this, Pordenone.

Paul Cuff