Day 8 of this year’s line-up from Bonn takes us to Hungary, where we plunge into a crime melodrama…

Rabmadár (1929; Hu./Ger.; Pál Sugár/Lajos Lázár). In the women’s prison in Budapest, the resident doctor (Charlotte Susa) takes pity on Prisoner No. 7 (Lissi Arna), who begs to be let loose just for one night. She explains that she let herself be arrested for the sake of a man. The doctor believes her intentions are noble, so swaps clothes with the prisoner and allows her to escape. Meanwhile, at a hotel in the city, the head waiter Jenő (Hans Adalbert Schlettow) dotes over his pregnant girlfriend Birdi (Ida Turay), while also eyeing up the new maid (Olga Kerékgyártó) – and then the new arrival, the artiste (El Dura). As Jenő forces himself on the artiste, Prisoner No. 7 rushes into the hotel. Spying on the pair from the next room, she sees the artiste turn the tables on Jenő – praying on his vulnerability (his lowly status), she lures him into making more of himself for her sake. The artiste thus inveigles Jenő to distract the hotel manageress (Mariska H. Balla), while she herself empties the manageress’s safe. This she does, but Prisoner No. 7, now armed, confronts the artiste just as she’s about to make off with the money – and without Jenő. Jenő re-enters and now the Prisoner confronts him, too. She phones for the police. The artiste makes a run for it, plummeting to her death in a faulty lift. The prisoner tells Jenő he mustn’t escape this time. Jenő claims he loves her and somehow lures the Prisoner into his arms. The police enter and find the body in the lift shaft. Jenő goes downstairs to becalm the police. Meanwhile, Birdie encounters the Prisoner – and we learn that her name is Annuska. Birdie reveals that she will be married to Jenő, and that she is pregnant. The shocked Annuska leaves, pursued by Jenő. On the riverbank, Annushka asks him to be decent and marry Birdie. He swears he will, and Annushka heads back to prison. ENDE

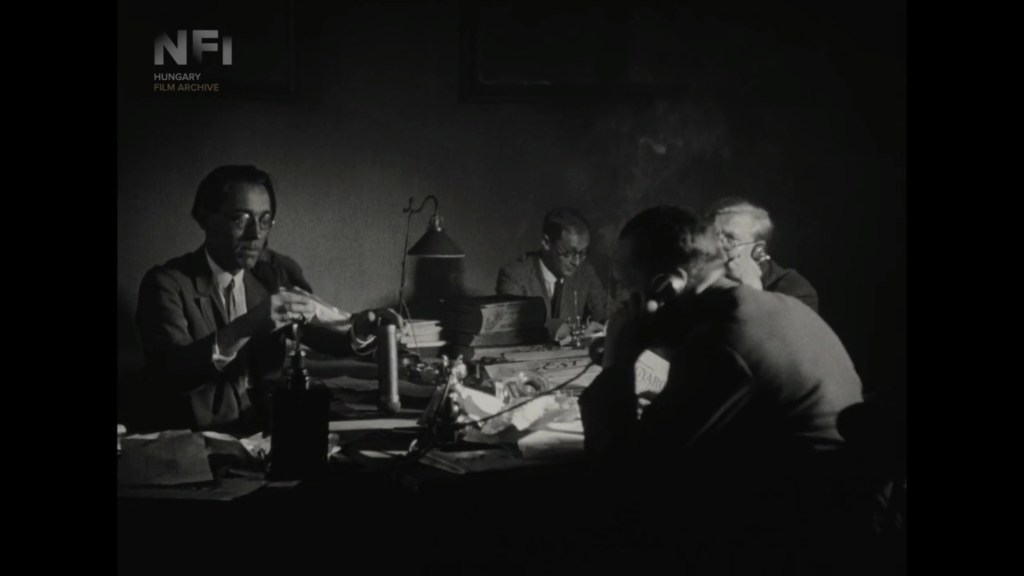

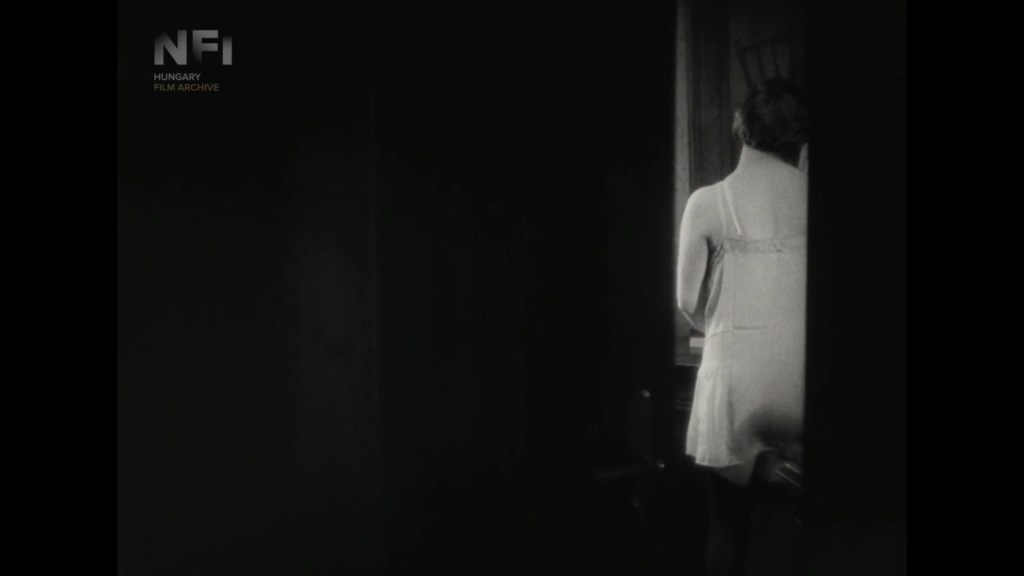

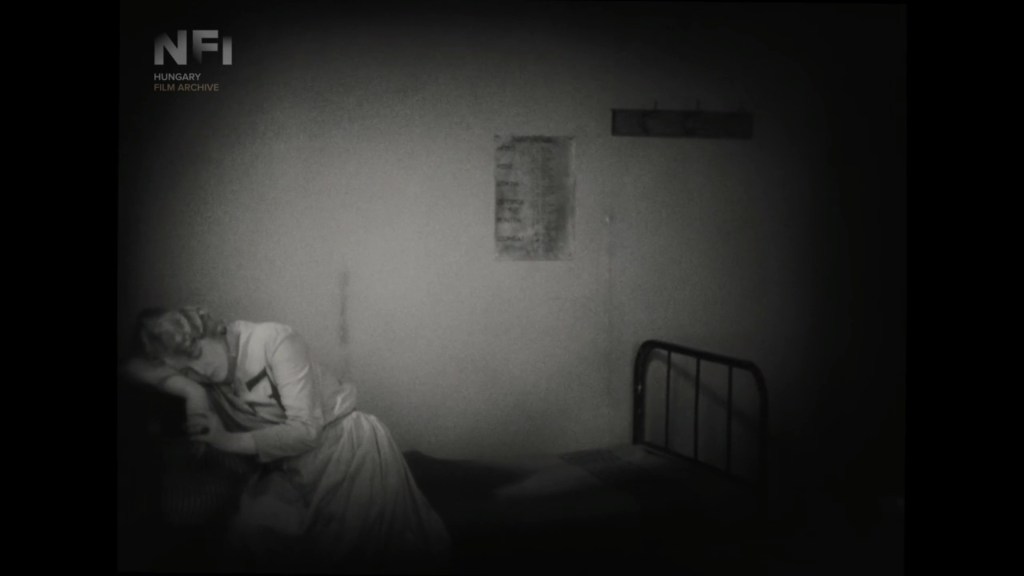

My word, what a film this is. My experience of late 1920s/early 1930s Hungarian-directed films has, perhaps by accident, tended towards the dramatically and expressively extravagant. If Rabmadár doesn’t quite have Pál Fejős (aka Paul Fejos) levels of emotional and aesthetic intensity, passages nevertheless have an amazing and unexpected potency. The film revels in dark, often sinister or oppressive interior spaces – from the jail cell to the hotel rooms and shadowy niches, and the dark or dawning streets outside. In particular, the prison setting boasts some wonderful imaginative camerawork and editing. As well as finding great angles to frame the prisoners, especially No. 7 – from up above, through grates – there is a superb sequence of Annushka’s claustrophobia. In tight close-ups, we see her eying the walls, the door, the ceiling, and the camera tracks in towards each surface, pressing them slowly into the lens. Multiple superimpositions and ever-closer shots of her face and mouth and eyes make us share the madness of confinement, as the film shoves us closer into its imprisoning world. Later, there are any number of superb close-ups. Even when the artiste is fleeing with the money, the film shows us the chasing figures in facial close-ups as they hurtle through the hotel, shouting and screaming. The set-up and story might be entirely generic, but my word this film makes the most out of the material. A simple story of crime and betrayal becomes a weird chamber piece, draped in a febrile mise-en-scène. This is what impressed me most: the fact that every aspect of design and camerawork gets used to heighten and intensify the emotional tone. Everything in this film seems intense.

But this isn’t merely an aesthetic exercise. The characters are the reason for the intensity, and the cast form a superb ensemble. Lissi Arna’s face carries such amazing fierceness of feeling, from the despair of jail, of shock, of fear, of betrayal, to the heights of gratitude, of longing, of love, of vicious triumphalism. It’s quite a performance, matched by the sultry, moody, dangerous presence of the others in the cast. El Dura is a remarkable presence. She’s such a slight figure, but she moves with amazing purpose – turning what seems to begin as a rape scene into something weirder and unexpected, turning on her would-be attacker and bending him to her will. It’s a mad, uncomfortable twist of narrative logic, but somehow El Dura pulls it off. And Hans Adalbert Schlettow as the superficial Jenő – always seen glancing at himself in mirrors, in glass, in any reflective surface – has just enough fun to make his character a believably engaging narcissism and charm over the women.

But it’s the women in the cast that have the most enjoyable, intense performances to offer. As the manageress, Mariska H. Balla has enormous fun falling for Jenő – proffering him with drink, with frilly sweets, with kisses. Their seduction/distraction scene together is delightful, almost absurdly so. When Jenő gets out his guitar and starts singing, you realize the almost autonomous strength of the scene and its performers – it’s like another, equally good, film is breaking out of the one we’re watching. Then there are the intensely believable performances of Ida Turay as the madly besotted, innocent Birdi, and Olga Kerékgyártó as the maid who, even in a handful of appearances, is somehow realistic, intense, emotional, and wholly believable as a person. Finally, the ostensibly minor role of the doctor is turned, by Charlotte Susa and by the intensity of the mise-en-scène, into a tangible, almost too powerful, emotional presence.

Speaking of the latter, I wondered quite what the connection between the doctor and her prisoner was to be, so febrile and physically intense were their jail scenes together. Even before they are seen together, the cigarettes that the doctor sends to Annushka trigger a dreamy, smoky vision of the doctor on the wall of Annushka’s cell. “Isn’t there someone you can’t live without?” the prisoner asks the doctor, on her knees before her, kissing her hands, pressing her year-stained face into her lap. (There is an implicit scene of mutual undressing, which the film avoids via a swift fade to black.)

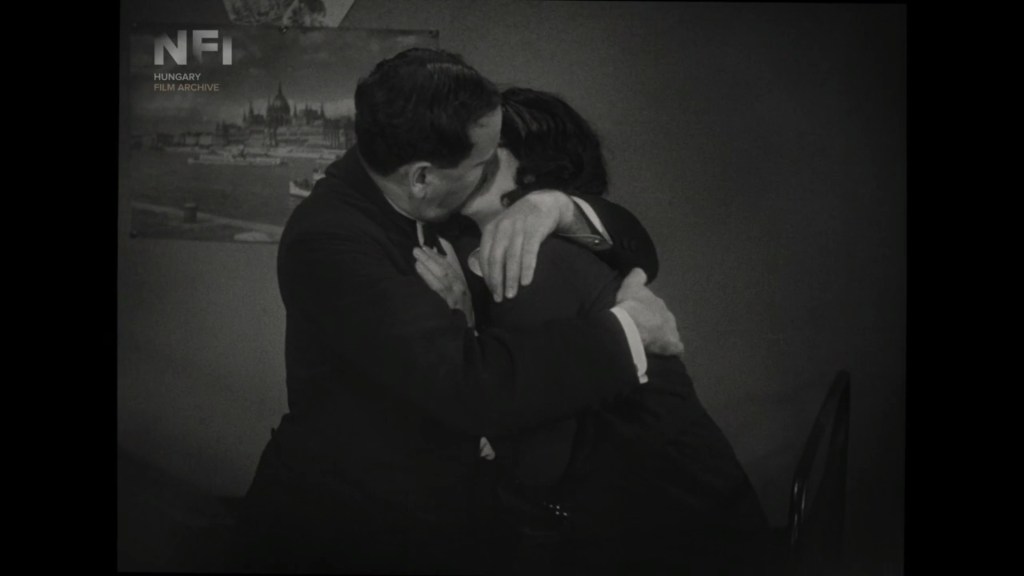

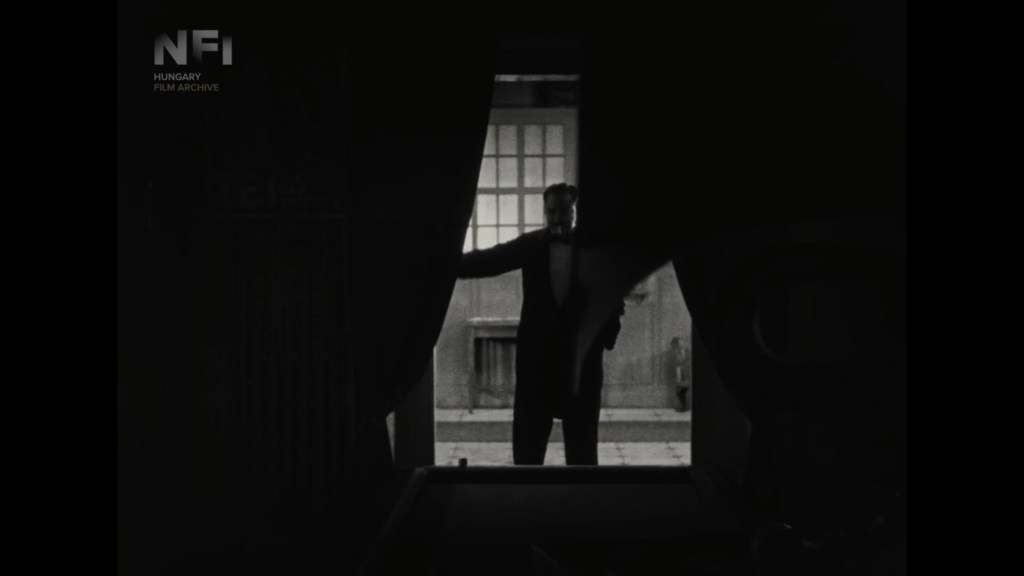

Later, when Birdi encounters Annushka in the hotel, it is Birdi who utters Annushka’s name for the first time in the film. It’s the first moment of identification, a form of intimacy. And Annushka embraces Birdi and kisses her several times on the mouth. This, too, is the first sincere kiss of the film. (We have seen Jenő kiss many women, always insincerely.) It is as if only without the central man in the story can any of the women find comradeship, tenderness – even physical tenderness. And at the end of the film, Annushka returns to the doctor – an odd and touching reunion of this couple. But the last image is of Annushka, alone, closing the shutters of her cell. It’s like the whole film has been some kind of nightmare of confinement, release, fear, and anger. No resolution is possible but a kind of sinking back into sultry longing.

A word must also be said about the history of the film and its restoration. A Hungarian-German co-production, boasting cast and crew from both countries, this film made a splash in 1929 but was long unavailable thereafter. The original Hungarian title was Rabmadár (“Slave Bird”), but only the German iteration – Achtung! Kriminalpolizei! (Gefangene Nr. 7) – survived in a print saved in the Netherlands, which was passed to Filmarchiv Austria, thence to the Budapest Film Archive. More cent discoveries enabled a longer restoration to be completed by the National Film Institute Hungary. Given the complex print history, outlined in the excellent restoration credits at the start of the presentation, the film looks sumptuous. Rich blacks, glowing highlights, detailed textures, glorious close-ups… quite simply, a delight to watch. My one reservation about the restoration would be the framerate. To my eyes, it looked like the film was transferred at a slower-than-natural framerate. For a print of 2171m, per the credits, the near two-hour runtime would indicate a framerate of 16fps, which seems unusually slow for a film shot in 1929. I can easily imagine 20fps working better.

Finally, the piano accompaniment for this Bonn screening/streaming was by Elaine Brennan. A rich, attentive score, engaging and sympathetic, perfect for the film. As ever, an excellent presentation from Bonn of a film that deserves to be better known.

Paul Cuff