This piece is about the various incarnations of The Sheik on home media formats. I write it out of curiosity and out of frustration. Curiosity because the differences between copies of silent films always interests me. Frustration because the object of my curiosity is obscured by the usual opacity and vagueness produced when historical artefacts become digital commodities. Let me explain…

Some years ago, a course on which I was teaching assistant (i.e. seminar tutor) scheduled a screening of The Sheik. Curious as to what copy we would be showing, I looked at the departmental copy: it was the DVD version released in the UK in 2004 by Instant Vision. It presents a monochrome version of the film with a soundtrack of… No, in fact I can’t even remember what the soundtrack was like. What I do remember is that it was such poor quality, visually and musically, that I couldn’t bear for any student on the course to experience the same in this way. (My general rule with screening material is that if I couldn’t sit through it, then neither should my students.) So I looked for alternatives.

Thankfully, there was at least the DVD produced in the US by Image in 2002. This presented a fully tinted version of the film. However, the score was by the “Café Mauré Orchestra”. Those inverted commas are there for a reason, since this “orchestra” is in fact composed of MIDI (Musical Instrument Digital Interface)-based synthetic sounds—as arranged and performed by Eric Beheim. Though the music choices used (but “used” doesn’t do the MIDI justice: should I say the music is sampled? digitized? synthesized? appropriated? co-opted? press-ganged? harvested? made vassal unto?) are appropriate, the sound of synthetic music rather undoes the benefits of the music itself. Put bluntly, MIDI soundtracks sound cheap. It’s the DVD producers saying: “Listen to how little money we’ve spent on the music! You’ll be amazed!”

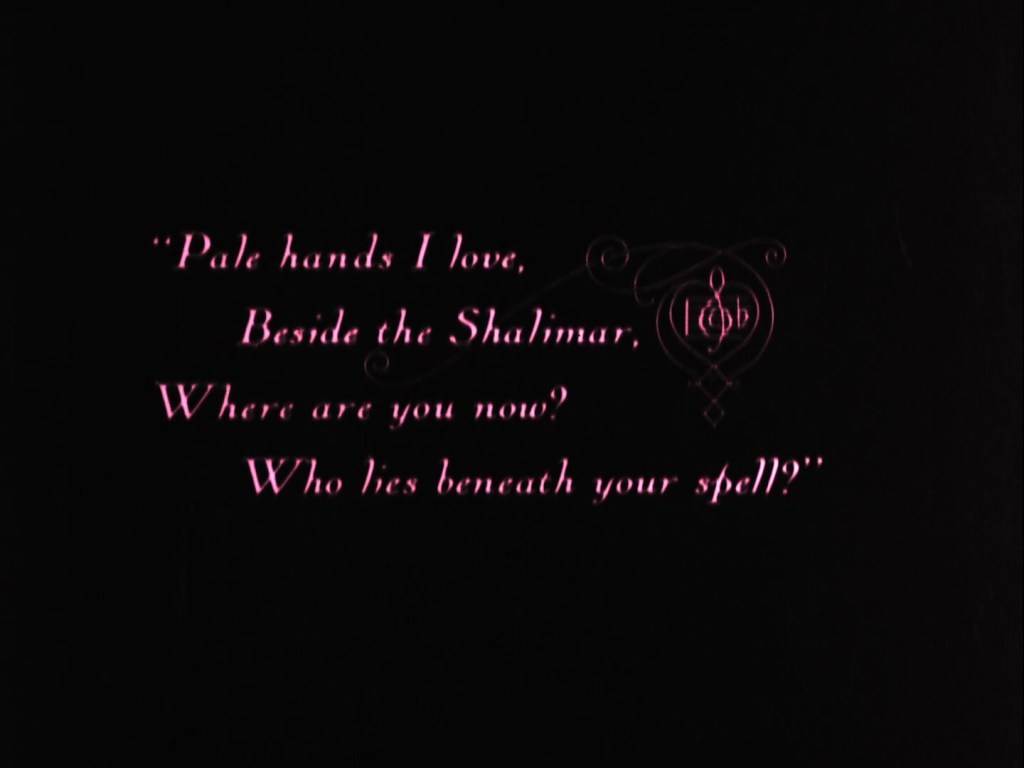

So I ripped the DVD and set about compiling my own soundtrack, one that used various nineteenth- and early twentieth-century pieces—including a nice orchestral arrangement of “Kashmiri Song” that Valentino’s character sings in the film. (I even used a couple of the cues from the Beheim score, only these were sampled from actual orchestral recordings.) It worked well and the students enjoyed the film. (More importantly, I enjoyed the film. There are few more maddening experiences in life—well, my life—than sitting through a silent film accompanied by bad music.)

The years passed. I no longer taught on the course that included The Sheik. (Or, for that matter, on any course.) So I was mildly curious when a Blu-ray of the film was announced in 2017. I was poised to buy it, if for the only reason that I try to buy almost anything silent that comes out in a good edition. But then I saw that the score was for theatre organ and my heart sank. (I know, I know, I’m a snob: but really, I just don’t enjoy sitting through over an hour of theatre organ music.) I also considered that my interest in the film was such that I had no real desire to actually buy the Blu-ray. My teaching days seemed to be over, so buying the Blu-ray to try rescoring the film again seemed pointless. I wouldn’t be watching the film, and nor would anyone else. So I passed. Of course, I should have bought the edition anyway. Kino often let their licenses expire, leading to a huge number of titles going out-of-print. Thus, The Sheik duly went OOP.

Paramount then announced their own edition of The Sheik would receive a Blu-ray release in November 2021. Still curious, I searched to see what information I could find about the restoration. I found an interview with Andrea Kalas, who leads Asset Management at Paramount. According to Kalas:

We looked around the world for best sources and Film Preservation Associates graciously loaned us a 35mm black and white print. We also had a finegrain which turned out to have a better overall picture quality, but the print turned out to be great for the intertitles. […] The original frame-per-second cadence was 22fps. The fine grain we used had been ‘stretched’ to 24—essentially by adding frames. With the help of the lab, Pictureshop, we went back to 22fps. […] We had a continuity script that was a critical guide to the digital tinting and toning we added – which was the way the audience in 1921 would have seen it.

The Paramount restoration promised to run to 66 minutes, nine minutes shorter than the Kino Blu-ray and a full twenty minutes shorter than the Image DVD. Kalas’ talk of reversing the stretch-print process of one of their source prints was reassuring—but if the film was “returned” to 22fps, why was the runtime so short?

All of which led me to some basic questions about The Sheik that no home media edition had addressed: How long was the film when shown in 1921? What projection speed was used? What print material survives? Thankfully, the American Film Institute database has some excellent material that is readily accessible. Here, I found that the original length of The Sheik was 6579 feet, which equates to 2005m. (IMDB.com states that the film ran to 1818m when shown in the UK, but I am less inclined to trust IMDB than the AFI when it comes to any film of this vintage.) Even if projected as fast at 24fps, 2005m would be 72 minutes. At 20fps it would be closer to 87 minutes. So how did the previous home media versions of The Sheik relate to this 2005m print, and at what speed did they run?

Well, here are the various incarnations (not including the infinitude of grey market rip-offs) and their runtimes:

- Paramount VHS (1992) = 79 minutes

- Image DVD (2002) = 86 minutes

- Flicker Alley (made-on-demand) DVD (2015) = 76 minutes

- Kino Blu-ray (2017) = 75 minutes

- Paramount Blu-ray (2021) = 66 minutes

Maddeningly, nowhere on any single home media release does any company—Paramount, Image, Kino, or Flicker Alley—actually state what the length of their copies are in metres. As a result, we must second guess frame rates and go through each edition to try and work out how they compare to one another…

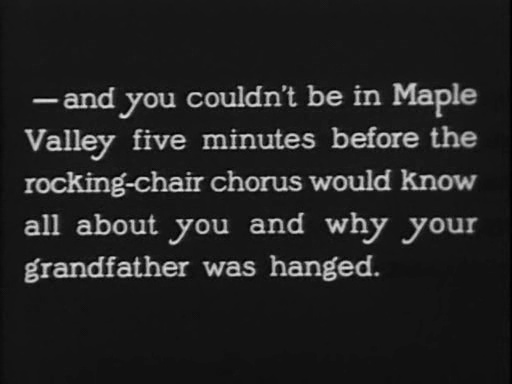

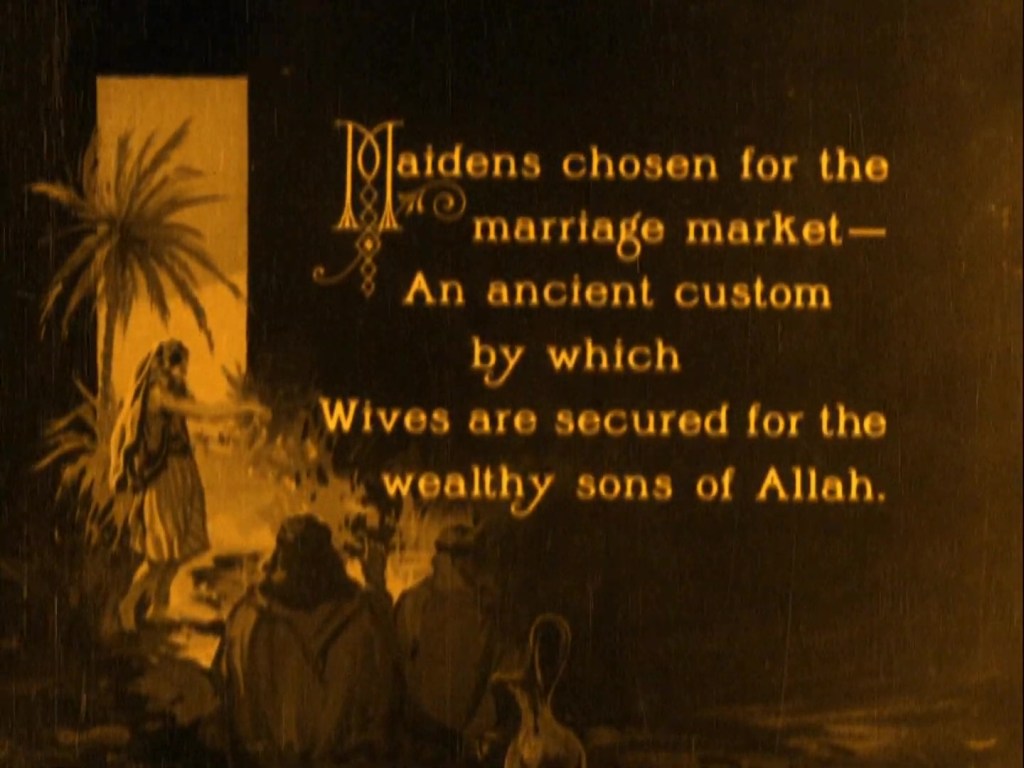

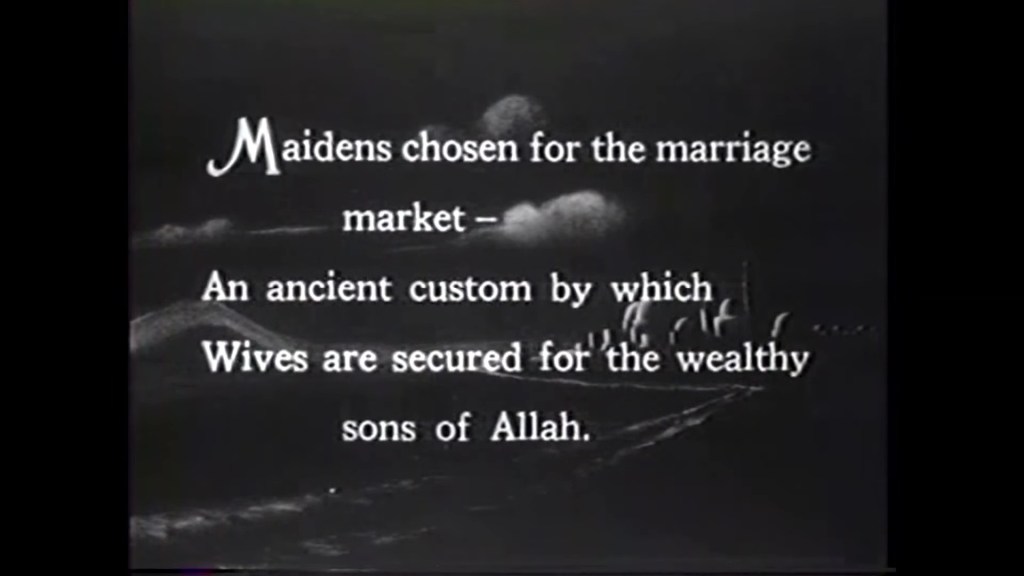

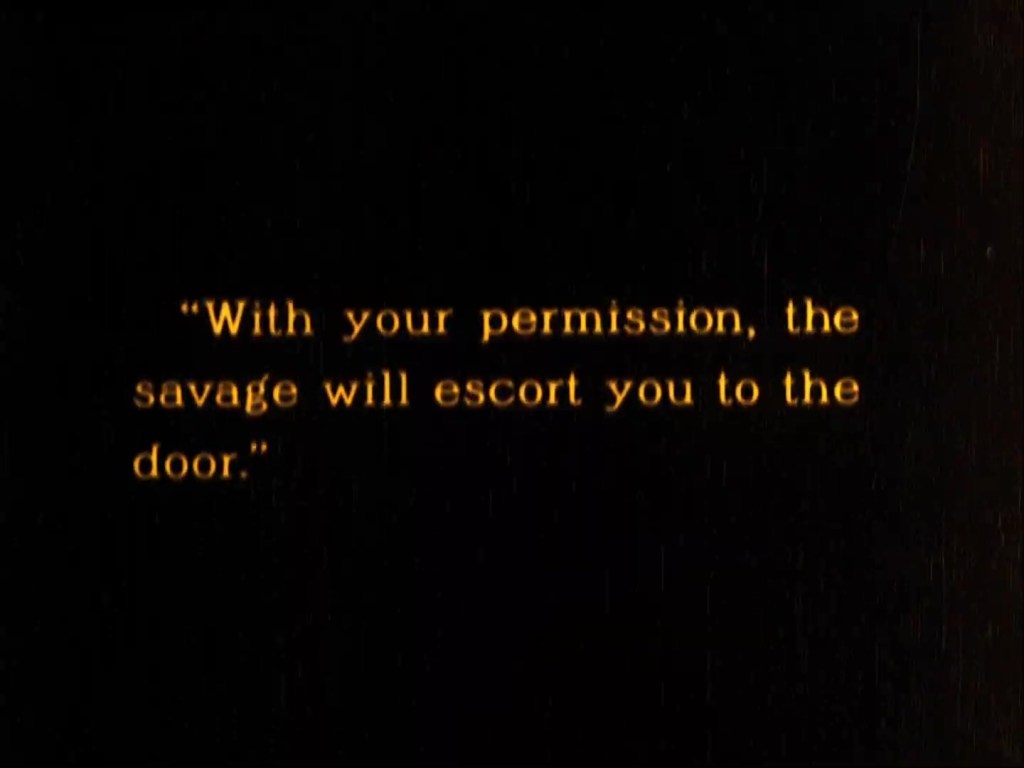

Though there are some minor textual differences between the copies (the Image DVD, for example, is missing one or two intertitles), the basic material remains consistent through these various home media incarnations. One notable exception is the Paramount VHS, which presents different intertitles to the later DVD and Blu-ray editions. The home media review for The Sheik on silentera.com states that the VHS used the re-edited and retitled version of the film, not the original. It’s ironic that the visual quality of the titles presented on the VHS is often superior to that of the DVD/Blu-ray editions: the titles in the reissue print are uniformly strong, sharp, and legible. It’s a shame that many of the original titles have not survived in such a state: after the very high-quality images of live action in the film (especially on Blu-ray), it’s a shock to have to squint at the slightly blurry wording of the titles.

The differences in runtime across the above home media editions are due overwhelmingly to the different framerates applied to the print sources. Deciphering the various video files of these editions has not proved easy, but I can offer an informed estimate of the rates for each. The Image DVD uses the slowest speed of 18fps, the Paramount VHS uses 20fps, Flicker Alley DVD and Kino Blu-ray use 21fps, and the Paramount Blu-ray uses 24fps. Kalas states that the film originally ran at 22fps, though my impression viewing the versions of the film that run to c.75 minutes at 21fps is that this seems perfectly life-like. (It may be that the projection speed used in 1921 was 22fps; but Kalas doesn’t go into any detail about this issue in the interview.)

I’ve checked the Paramount disk and (shorn of new opening/ending credits) the film does indeed last 66 minutes (and nine seconds) and runs at 24fps without any repeated frames. At 24fps, 66 minutes equates to an approximate print length of 1830m. That’s still 175m (6-8 minutes, depending on projection speed) short of the film as seen in 1921. Some of this might be accounted for in the length of intertitles, but it’s still a not insignificant amount of material for such a short film (nearly 9% of its length). I’ve also checked the Paramount Blu-ray against the Kino Blu-ray. It appears to be exactly the same restoration. And I mean exactly the same. The same tints and tones, the same titles, the same scratches and damage. The only difference is the framerate and the soundtrack. I can only presume that Paramount’s centenary restoration of The Sheik was completed by 2017 and Kino simply licensed this version to last until the actual centenary of the film, whereupon Paramount could release their own edition. But why on earth does the Paramount Blu-ray transfer this same restoration at 24fps?

The decision is even stranger when you consider that the soundtrack for Paramount’s Blu-ray—a synth score by Roger Bellon—is the same as the one on Paramount’s VHS thirty years ago. Although Kalas claims the music was “commissioned in 1990 as part of a celebration of Paramount’s 75th”, the VHS edition from 1992 bears a copyright date of 1987 for the soundtrack. (According to various reviews of older home media editions, The Sheik was first released on VHS by Paramount in 1988. I’ve not been able to find any VHS from 1988, only the edition from 1992.) Kalas adds that Bellon’s music “really stands up”, which again begs the question why transfer the film at 24fps when the soundtrack was arranged for a version of the film that ran at 20fps? Another issue with the Bellon score is that it never uses the “Kashmiri Song” that is cited in the film’s intertitles and sung by Valentino on screen. This may well be because the intertitles of the VHS version (for which the score was composed) are from the reissue print, which changes the wording of the Sheik’s song—and thus loses the context of the original song. (While no substitute for a real orchestra, the theatre organ score by Ben Model for the Kino edition at least quotes the “Kashmiri Song” at the appropriate moments.)

Paramount are not alone in sidelining the complex issues and inevitable compromises of film restoration in their home media salesmanship. But in the past I have been irritated by the way some of their press releases muddy the waters of what editions are being presented on Blu-ray, and how they relate to the films as originally presented in the silent era.

For example, their 2011 Blu-ray release of Wings (William A. Wellman, 1927) was announced with a press release that detailed how they had restored the original score composed by John Stepan Zamecnik (plus the numerous sound effects that were a feature of the film’s initial release). This “newly-restored” soundtrack was announced as the culmination of great effort:

the film’s original paper score was procured from the Library of Congress and recorded with a full orchestra […] Musicians with expertise in silent film music were chosen to recreate a truly orchestral experience.

Note the references to physical artefacts and institutions: paper score, material archive, real musicians. They echo the dual boast of historical sources and modern technologies: celluloid prints scanned using HD software, sheet music from 1927 recorded in 5.1 Dolby Digital Surround sound.

But there is a good deal of ballyhoo (if not bullshit) here. For a start, the only surviving hard copy of the music for Wings was a conductor’s short score, bearing just two or three staves of information. This document lacked details of orchestration, and the structure of its cues did not match the montage of surviving prints. The task of re-editing the score was further hampered by copyright issues: Paramount could not include (or could not afford) several of the musical works originally quoted at length by Zamecnik. And the reorchestration of this music was performative as well as editorial. Contrary to the press release, Dominik Hauser’s arrangement of the “orchestral” score on the Blu-ray is not performed by an orchestra, but instead consists of an assembly of MIDI sound files. The only real musician audible on the soundtrack is Frederick Hodges, whose solo piano interpolations were needed to bridge gaps in the “orchestral” score. Whilst the Paramount edition includes an alternative soundtrack of Gaylord Carter’s organ score, it does not offer Carl Davis’s orchestral score, which was recorded with real musicians for the Photoplay restoration of Wings in 1993. This latter version has never received commercial release.

The spin around Paramount’s release of Wings made me more suspicious than I might otherwise have been when it came to their release of The Sheik. My heart sinks that in 2021 Paramount offered a less satisfying presentation of their own centenary restoration than Kino presented in 2017. (I might add that the Kino edition included an audio commentary track on the film by Gaylyn Studlar, which the Paramount edition lacks. Even if Paramount had been willing and able to reuse this commentary, they would have had to speed-up the track by 114% to match their 24fps presentation of the film.) I have no particular fondness for The Sheik as a film, but even just as a historical document it deserves to be treated with respect. It’s great that Paramount decided to restore and release this silent film on Blu-ray. But why then make choices that lessen its impact?

Paul Cuff