This week, I return to Portugal. Having been exceedingly impressed by Maria do mar (1930) at the Stummfilmtage Bonn in August, I tracked down the DVD of the film from the Cinemateca Portuguesa. Finding that the Cinemateca has produced a whole series of DVDs of recent silent restorations, many with the original scores, and all with English subtitles, I took the plunge and placed a large order… Within a few days, I had a mouthwatering pile of films in beautiful presentations. Where to start? Why not with the film that the notes describe as “the most beautiful use of colour tinting and toning in Portuguese silent cinema”? A bold claim. But having watched O Destino, I can well believe it…

Let’s begin with the plot. (Yes, obviously, there will be spoilers.) The bereaved Maria da Silva de Oliveira returns from Brazil to her native home of Sintra to visit her daughter, who is also called Maria. After a road accident knocks her unconscious, she wakes in the palace of the Marquesa de Souzel. Here, the scheming Luís de Noronha has recently become the Conde de Grazil and thus has taken charge of the family estate. He has his eyes on Maria’s daughter, but so does his young nephew André. Meanwhile, the old housekeeper, who went blind with grief after his daughter was “disgraced” and left home twenty years earlier, wanders the estate mourning his past. These two stories are brought together when it becomes clear that Maria is the lost daughter, and that the man who disgraced her was none other than Luís. Maria decides to confront Luís, whom she – with the aid of the supportive de Souzel family – finally exile, enabling the engagement of her daughter Maria with André. FIM.

O Destino is directed by Georges Pallu, a French director whose five years in Portugal makes him one of the major figures of Portuguese cinema of this era. This film marks the only cinematic appearance of Palmira Bastos, a celebrated theatre actor. I had only the sketchiest knowledge of Pallu as a name, and none of Bastos as a performer. I therefore went into O Destino blind and was intrigued by the dramatic set up of the opening half hour or so. Pallu lets most scenes play out in long takes, with sparing use of medium and medium-close shots – and no true close-ups. I wondered if there were some missing titles in the opening, since only a couple of the characters were properly introduced – so it took a while for their relationship to sink in. What intrigued me was the fact that, despite minimal editing during scenes, Pallu kept longer sequences interesting by parallel cutting. In the opening reel, the family tensions of the de Souzels take place parallel to Maria’s arrival by steamer from Brazil. Pallu cuts between the estate and the approach of Maria (by boat, by car, and ultimately by foot) – building a kind of slow-burning tension as to when the two stories will finally meet. They do in marvellous fashion – quite literally colliding on screen when Maria’s taxi smashes into a truck, hurling her into the road. She is then carried into the palace, and she wakes up in the very site of her childhood. It’s a terrific way of introducing Maria into the drama.

That said, I found the first half of the film dramatically slow going. The relationships are carefully established, but I was never gripped by the emotional tenor of the drama. Maria spends too much of the film inert in bed, carefully avoiding contact with the man who impregnated and then abandoned her twenty years ago – and with her father. This means that the only on-screen conflict is between uncle and nephew over Maria’s daughter, which is a little uninteresting.

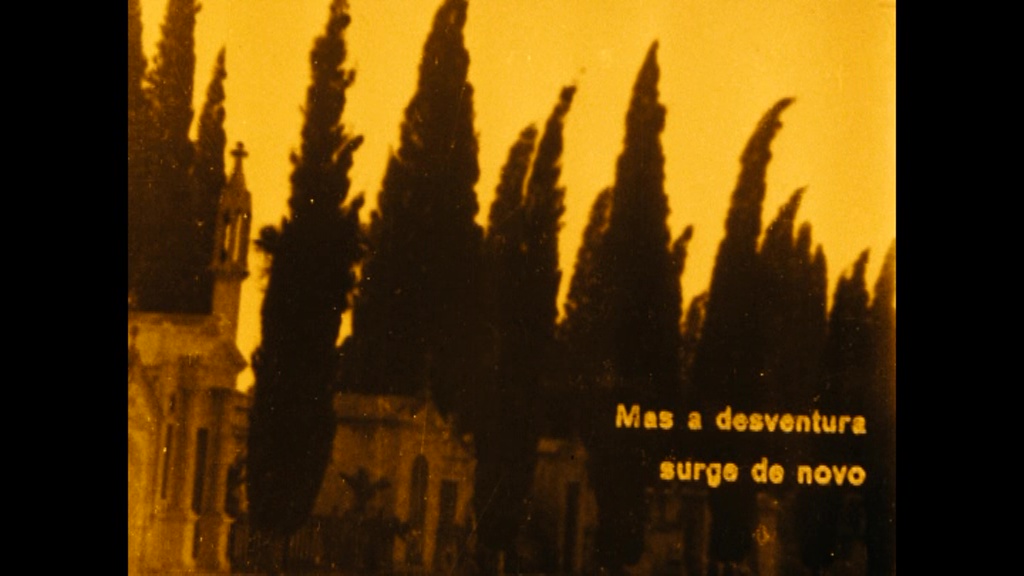

What saves this half of the film, lifts it indeed into the realm of the extraordinary, is the photography. Seen on my television screen, I thought the exterior scenes in O Destino among the most beautiful I have seen in years. Every new shot brings some astoundingly lovely vista of backlit trees, sparkling water, sun-dappled road, or rich parkland. The lighting is equally impressive in the large interior of the house, where Pallu allows natural light to create superb, rich, shadowy spaces inside the architecture. The lush pictorial beauty is enhanced by the tinting and toning, which creates a new mood for every scene. It’s stunning, just stunning. The cameraman was Maurice Laumann, whom I had not heard of – whoever he was, he did grand work here. I longed to see this film on a big screen. It’s simply wonderful to look at.

(A small footnote to this enthusiasm is that the lighting looks less effective when I went through the film and took captures from the DVD. The settings on my monitor are surely different from that on the television. I have the latter on “cinema” mode, so the contrast is not too exaggerated – but it has clearly made a difference. This clearly raises all sorts of questions about home viewing, but I must be loyal to my initial reaction: I was incredibly impressed by the way the landscapes looked on screen.)

As I said, I confess that I wasn’t much gripped by the drama of O Destino until about halfway through. At this point, Maria is alone in the palace and, instead of joining the household at the fireworks in the park, she decides to walk round the gardens of the estate. It is here, in the still, dim light – tinted a kind of dusky green – that we see her truly express herself, and where the film really taps into the emotional depths of her character and past. As she wonders alone through the gardens, Pallu once again uses parallel cutting to heighten the effect of Maria’s loneliness. We see her slow, quiet walk intercut with the sudden bursts of colour (pink, gold, green) of the fireworks, together with the boisterous crowds. These scenes are magnificently tinted and toned, enhancing the amazing chiaroscuro lighting of the dark park. But they also function to make Maria’s scenes seem quieter, more isolated. The film has much in common with the kind of “diva” films produced in Italy in the 1910s, and these scenes of a female protagonist walking in black veils through gorgeous surroundings had very much the same aesthetic feel. Bastos’s performance grows in stature across the film. I didn’t quite get the fuss over her status to start with, but by now her control and dignity on screen attained its full emotional weight. I found this sequence, and the climactic encounter between father and long-lost daughter, very moving. It also helps that the motif in Nicholas McNair’s piano score is a slow, gorgeous, memorable sequence of romantic chords. The whole sequence has a magical, dreamlike effect, which the music captures and enhances perfectly. What a gorgeous piece of cinema this is. Even the sudden way it ends – with Maria planting a kiss on her father’s head, his gesture of astonishment, and the end of the reel – is perfect. It’s a great, great sequence – and from this point to the end, the film really works.

One of the reasons it works is that Maria assumes greater agency. She finally deals with the legacy of the past, confronts Luís, and speaks to her father. The way she lifts her veil to reveal herself to Luís is a fabulous moment. It’s one of the many scenes that belongs in an opera by Verdi. I could easily picture scenes and sequences being transposed into arias and duets. The fact that it gives this sense of big emotion through such economic, silent pictorial means, is a marker of the film’s success. I love the way the film ends, too, with Luís being cast into exile. The film begins and ends with lone figures, silhouetted against the dazzling waves. That Maria is now at the heart of her family, and Luís is banished from Portugal, is deeply satisfying.

If O Destino is slow to get going, by the end I was totally absorbed by it. I can see why this was “the biggest commercial success” in the silent era in Portugal. It looks preposterously good. I can’t emphasize enough how hypnotically beautiful these exteriors look. The depth of shadow, the lustre of the light. I think I would be overwhelmed by this on a big screen. Nicholas McNair’s piano score was very good, and he brought out some lovely themes for Maria’s scenes. As I say, by the halfway point I was won over. Bravo to all involved in restoring this film. I can’t wait to dig into the rest of the Cinemateca Portuguesa DVDs – including more films by Pallu…

Paul Cuff