Recently, I wrote about Charles Koechlin’s The Seven Stars’ Symphony (1933), a remarkable musical evocation of stars from the silent and early sound era. This week is a kind of sequel, devoted to another obscure late nineteenth/early twentieth-century French composer. Louis Aubert (1887-1968) was (like Koechlin) a pupil of Fauré, was well respected by Ravel (whose Valses nobles et sentimentales he premiered as a performer), and made his name as a composer with the fairytale opera La forêt bleue (1911). Though he produced numerous works for piano and for orchestra, his work is rarely heard today. Indeed, there is only one modern recording of some of his orchestral works—and it was through this CD (released by Marco Polo in 1994) that I discovered Aubert in the first place. I found it at a local Oxfam for £2.99 and wasn’t going to turn down the chance to encounter another interesting obscurity.

What really sold me on it was the fact that one of the works on the CD was called “Cinéma”, six tableaux symphoniques. Very much like Koechlin’s symphony, this suite offers six portraits of various stars/aspects of cinema. (The recording with which I’m familiar is only available in six separate videos on youtube, so I have included links to each movement below.) Unlike Koechlin’s symphony, however, Aubert’s music was originally designed with a narrative purpose. In 1953, Aubert wrote a score to accompany a ballet called Cinéma, performed at the Paris Opéra in March 1953. This offered (according to the CD liner notes) a series of “episodes” from film history, from the Lumière brothers to the last Chaplin films “by way of Westerns and stories of vamps”. I’m intrigued by the sound of all this, though I can find only one image from the performance—depicting Disney characters (see below)—to suggest anything about what it was like on stage. I also presume that the ballet consisted of many more musical numbers than are selected for the “six tableaux symphoniques” that is the only version of the score that appears to have been published (and certainly the only portion to be recorded). Nevertheless, the music is a marvellous curiosity…

Douglas Fairbanks et Mary Pickford. Here is Fairbanks—listen to that fanfare! Drums and brass announce his name. The strings snap into a march rhythm (off we go: one-two! one-two! one-two!). but then the rhythm slows, fades. Harp and strings glide towards a sweeter, softer timbre. Mary Pickford swirls into view. But there is skittishness here as well as elegance. The music is lively as much as graceful. There is a kind of precision amid the haze of glamour, strong outlines amid the shimmer of sound. A drumbeat enters the fray, then cymbals and snare bustle in. Doug has bustled in, caught Mary unawares. His music sweeps hers away. He’s busy doing tricks, showing off. The music cuts and thrusts, leaps, jumps—and lands triumphantly on the downbeat.

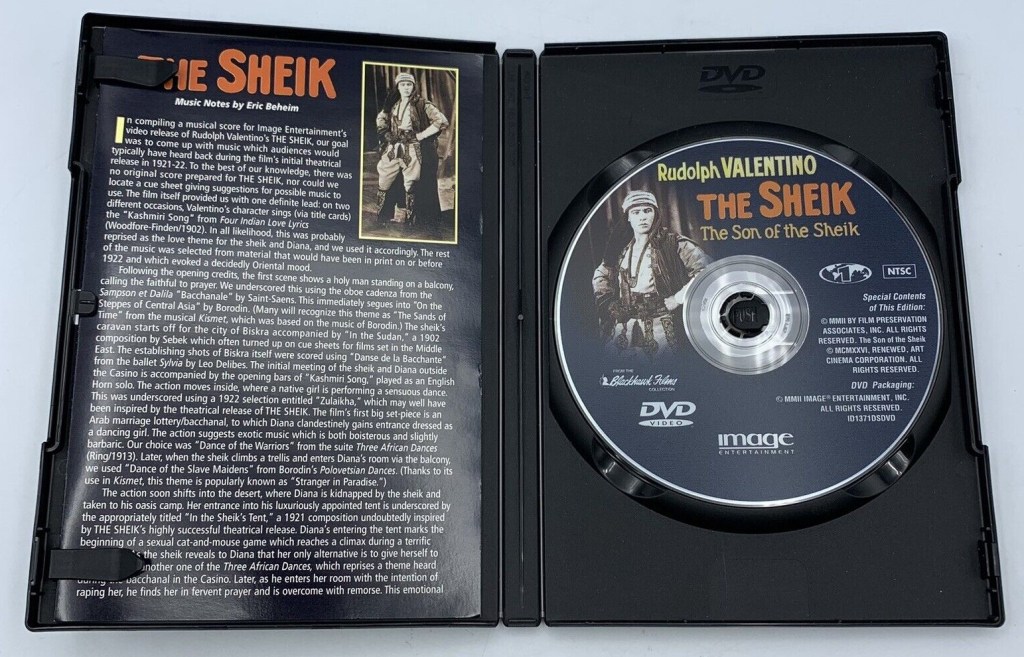

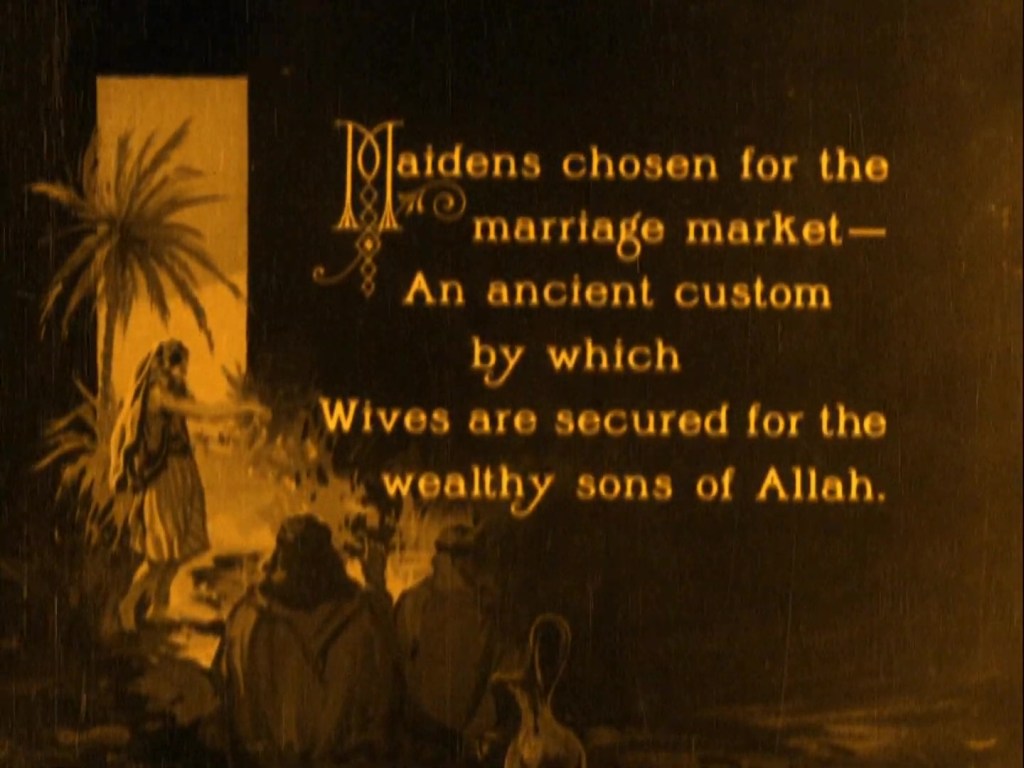

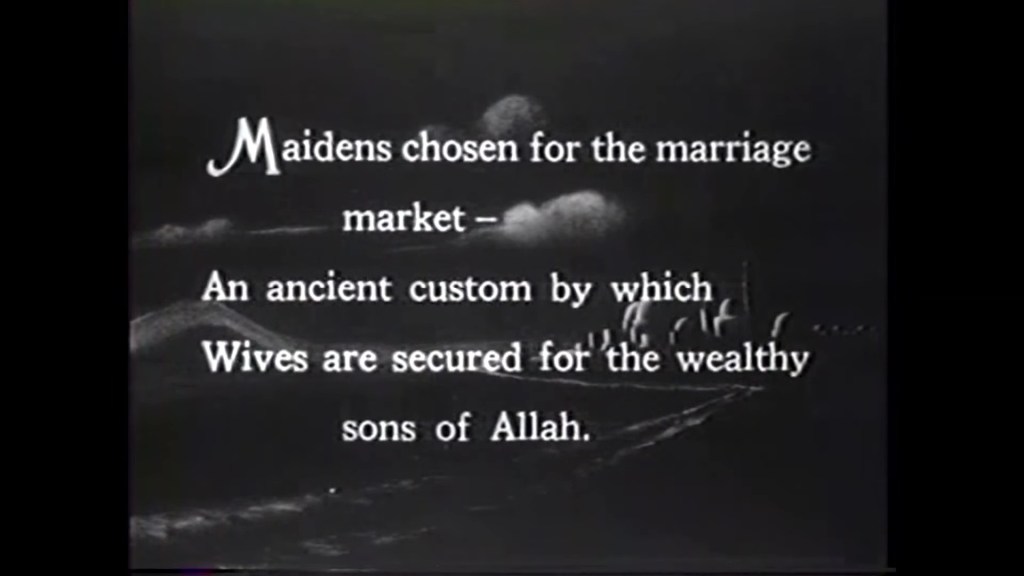

Rudolf Valentino. After a boisterous introduction, a sinuous saxophone melody unwinds across a busy pizzicato rhythm in the strings. It’s a superb image the music conjures: a kind of rapidity amid a vast, unchanging landscape. Surely this is the image of a desert, of Valentino in The Sheik, riding across an immensity of sand. But it’s also nothing quite like the film itself. It’s a memory, a mistaken recollection. And the music develops this simple idea, building slowly in volume. (More like the famous first shot of Omar Sharif’s character in Lawrence of Arabia than a scene in The Sheik.) Then figure disappears, riding off into the distance. Fade to black.

Charlot et les Nymphes Hollywoodiennes. Here is Charlot! Bubbly, jaunty rhythms. There’s a jazzy swagger, rich twists of sound. A violin solo breezily dances over the brassy orchestra. The drums are played with brushes: a pleasing, rustling soundscape. Then all is wistful, dreamy. A solo violin dreams over gentle strings, over warm breaths of woodwind, over a muted trumpet call.

Walt Disney. Almost at once, the music is mickey-mousing across the soundscape. But the orchestration is also weirdly threatening. It’s as if Aubert is recalling the sorcerer’s apprentice section of Fantasia, threatening to take Mickey on a perilous journey. And there he goes, marching off—the percussion jangling, as though with keys in hand, walking edgily towards a great door that he must open, behind which is the unknown…

Charlot amoureux. Another facet of Charlot. Wistful, dreaming, languorous. A private world, an inner world. (One can imagine the Tramp falling in love, comically, tragically, delightfully.) But reality intervenes. A blast of sound, then an awkward silence. Quietened, tremolo strings swirl under an ominous brass refrain. It is love lost, abandoned, proved false, proved insubstantial, unobtainable, unrequited.

Valse finale. Hollywood bustles in. The orchestra sweeps itself into a waltz. It’s grand, if a little undefined. Here is glamour in sound, showing itself off for our appreciation. It makes me think of Carl Davis’s glorious theme for the television series Hollywood: A Celebration of the American Silent Film (1980). But, as so often, Davis has the genius to make his melody instantly memorable—conjuring in the space of two bars an entire world, mood, and feeling. Aubert’s waltz is both less memorable but more orchestrally substantial (it is, crudely, louder, written for larger forces). So it’s at once dreamy and unwieldy, a kind of too-crowded dancefloor. You can’t see the stars for the wealth of movement, of swishing figure, of gleaming jewels. (Glockenspiel and triangle chime and jingle.) The music swirls and swaggers to its inevitable conclusion: THE END.

Aubert’s score is (I think) less musically inventive—less outlandishly exotic in tone and texture—than Koechlin’s Seven Stars’ Symphony. The CD linter notes (by Michel Fleury) argue that Aubert’s music is (like Koechlin’s) more interested in creating mood pieces than in recreating specific scenes from films. But I wonder how true this is. After all, the music accompanied specific dramatic action on the stage. Listening to it, I can more readily imagine it accompanying images/action than I can the majority of Koechlin’s score. I could even see the music working well as silent film accompaniment, and I wonder if the original ballet mimicked this very strategy in the theatre. As with Koechlin, I want to know what kind of experiences Aubert had with the cinematic subjects he depicts in music. Did he go to the cinema in the silent era? If so, what kind of music did he hear there? I’d also ask similar questions about the ballet of 1953: what kind of a history of film did this present, and what inspired it? (And what did the spectators think of it, especially those who knew the silent era firsthand?) Many questions, to which I currently have no answers. But I’d be intrigued to find out more, and may (in time) do a little more digging to find out. In the meantime, we have Aubert’s music, which is well worth your time. Once again, go listen!

Paul Cuff