Day 8 is our final day of films from Pordenone, and it’s another busy schedule. Our first programme takes us on a journey from the Middle East to South America and eastern Europe, from haphazard observations to machine-tooled propaganda. Our second programme gives us a comic fantasy and a comic reality, taking us from wartime Ruritania to postwar America. It’s a great range of films, and they appealed to me in unexpected ways…

Aleppo (c.1916; Ger.; unknown). Camels kneel and rise. Soldiers and civilians mill around. Awkward looks at the camera. Views of the city, of a cemetery, of ruins, of waterways, of Arab children. It’s very beautiful to see this faraway land, and this faraway time, so calmly recorded. But of course this is 1916, and the world is at war. This is a Syria under Ottoman rule, and the European men in tunics and caps are the Turks’ erstwhile German allies, still confident in victory. These uniforms and trucks, these crowds of Turkish soldiers – they are all part of some other continuity, some other subject. The film cannot but admit that something is going on elsewhere, something unnamed, something momentous. In this other place, everything is decidedly not calm. But here are the boys and their donkeys, and the old men and their pipes, and the ruins of epochs long gone. This is a world in waiting, then, getting on with life somewhere between ancient history and the crucible of the twentieth century. The film ends, and in the fade to black, history surely intervenes.

La Capitale du Brésil (1931-32; Br.; unknown). Fed information by title cards, we arrive by sea. The camera slowly bobs with the ship’s passage through the waves. Crowds await us. The camera is on the shore and onboard. Our view changes with the ease of a page turned in a travel brochure. From the rooftops, we see sunlight fall over the streets of Rio de Janeiro. The camera pans over the coast, the mountains, the distant houses. The world goes about its business. The beaches are crowded, the waves lap over the shore. Cable cars and light railways take us up the mountain of Corcovado, and – after so easy an arrival – we glance down towards the distant city, the huge arcs of hills, the bay. At sea again, we take the ferry and glide past beautiful islands. Then to the institutes, museums, gardens – the taming of this wildness. Then to views of sport, from rowing to football and tennis, and the Jockey Club. Crowds of men and women beam at the camera. A sea of hats and smiles. We visit the gold club, the polo club. A smiling, hatted, patient, affluent crowd. Life stretches out amiably before them. We are tourists, and they are showing us the life to which we might aspire. It’s very bourgeois, very decorous, very charming. (There is little life.) The last we see of this world is the patient spectators of a peaceable game, watching their world play out. The film stops, and they are swept away into the past.

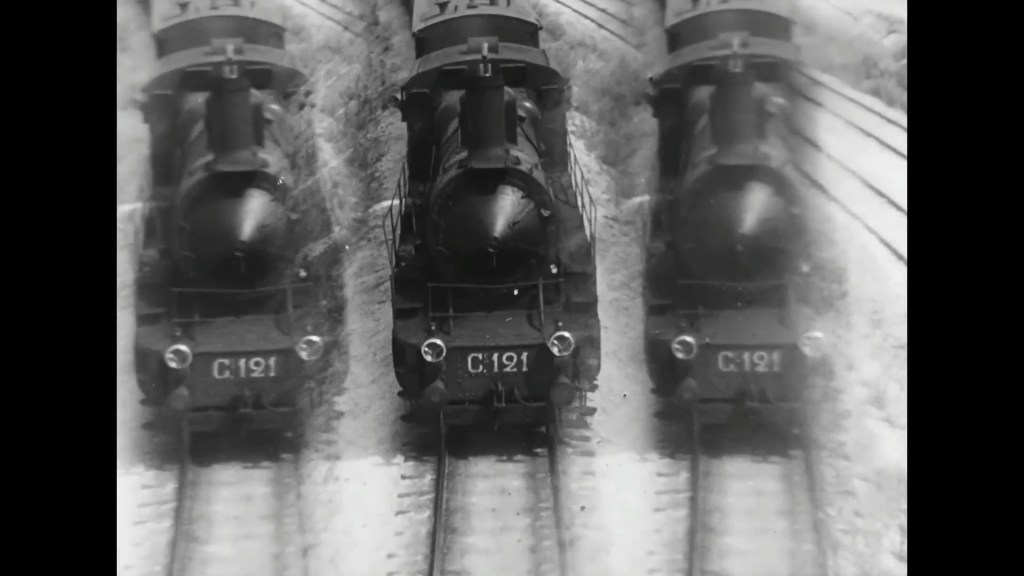

Narysy Radanskoho Mista [Sketches of a Soviet City] (1929; UkrSSR; Dmytro Dalskyi). A swirl of images, an advancing tractor, swaying fields of wheat, piles of vegetables. Here are forests, and the trees being felled. Here is produce and fuel, and here are the men and women, and the trains and ships, and the factories. “From all sides of Ukraine…”. Trains arrive at Kharkiv, and Kharkiv is at work. The streets, viewed from new buildings. This is a past that is very busy. They like to think they are building the future, and perhaps they are. “The future belongs to us!”, and the film cuts to a dinosaur skeleton, to museums of ancient artefacts, to statues and books. “This all belongs to the workers”, and the workers study and read. But such a film leaves its viewers little time to think. All the thinking has been done for us. The film is merely the precis of a conclusion already written and approved. It is all madly exciting, madly busy, madly optimistic. The past here surges with energy. There is no time to dwell or to reflect. Everything is happening now. “Not a step back from the current pace of industrialization!” Slogans fill the screen, and the workers work at insane pace, in insane numbers, across every conceivable facet of production. With a last surge of statistical overachievement, the film ends. But it might just as well have gone on forever.

The whole thing reminded me of the montage in Fragment of an Empire (1929), wherein the factory workers convince the newcomer of the benefits of the Soviet system. But as I wrote about that film, the unending montage of Sketches of a Soviet City is unconvincing as any kind of argument. Indeed, it isn’t an argument so much as an unceasing statement: a statement of achievement, a statement of intent. The film is organized into a series of visual slogans, interspersed with written slogans. Though it has momentary glimpses of real life, the film bundles everything together into a package of remorseless optimism that loses sight of the human beings it claims to represent. The pleasure one takes in this film a century later is not the message so much as the glimpses of people and places it contains. These pleasures are fleeting, since the film is in such a mad rush to boast about how these people are being mobilized toward ever greater productivity. Everything is a resource to be moved, pushed, pulled, dug up, processed, transported, melded, welded, stacked, cemented, launched, turned, electrified. It’s impressive, but it quickly becomes exhausting. Unlike Aleppo, this film is at least up front and explicit about its political context. But there is more real life, both in its spatial randomness and temporal slowness, in Aleppo than in Sketches of a Soviet City. For all its avant-garde technique, the Soviet Ukrainian film is less enticing as a vision of progress, and an enticement to visit (or at least admire) than the bourgeois world presented in La Capitale du Brésil.

So to the day’s second half. We begin with the half-hour short, Soldier Man (1928; US; Harry Edwards). Harry Langdon is the soldier the army forgot. He has been left behind in “Bomania” after 11 November, not realizing the war is over. He stumbles around, fleeing phantom enemies, confounding local peasants. Meanwhile, King Strudel the 13th of Bomania (also played by Langdon) is fighting revolution, secretly being fermented by General von Snootzer. The Queen of Bomania hates the King for his drunken loutishness. The King is duly kidnapped and hidden in a remote barn, to be killed in due course. But the King’s loyal courtiers encounter Harry and recruit him to impersonate the missing monarch. He does so but is immediately the target of an assassination attempt by the Queen. However, it turns out that he’s a better kisser than the real King, so the Queen is disarmed. Things turn suddenly romantic, but Harry is tired. He goes to sleep on the King’s bed and wakes up in his real home with his real wife. He is a common soldier, after all, and the war is over. THE END.

I confess that I’ve seen very little of Harry Langdon in my life. The handful of features and shorts I have seen left me curious, but clearly not curious enough. So I was very glad to see him here, exhibiting all the curiosity I remember. He’s not quite a child and not quite an adult. He seemingly has sex appeal, but of an innocent kind. His appetites are easily assuaged: all he really wants is a bite to eat and a place to kip. In Soldier Man, I love the way he traverses the world so harmlessly. His gun is broken, but when he fixes it it’s only to shoot a scarecrow. When he takes cover behind a cow, he pauses to marvel with curious pleasure at its udders. He is about to paw at the suspended teats but withdraws his hands before any kind of groping might take place. The cow bends its neck to look at him, so he smiles – so innocently and friendlily – back at the animal. It’s a curious, charming, silly, almost sad little moment. It’s all incidental, puncturing the chance of threat, denying the danger of physical contact. It’s making nothing out of something.

Though Langdon also plays the King, his double, this character is swiftly bundled off screen before Harry arrives. There is no attempt made for Harry to meet his doppelganger, to see the kind of man he might otherwise have been (aggressive, selfish, sexual, powerful). It is the innocent Harry who wears the outsize royal robes, and we might wonder how they can be outsized when they were made for his other self – for him. It is as though he is figuratively smaller than his own doppelganger, so that even identical clothes do not fit. His royal regalia are superfluous to his needs. He offers his crown to a courtier, as a vessel for him to vomit in – since Harry is so innocent he cannot think of another reason why the man should bow forward. Somehow, perhaps by sheer lack of arrogance, the Queen is seduced by him. Harry is hardly interested in her at all. She tries to kiss him, to distract him from her dagger, but he’s too busy eating a biscuit to have his mouth and lips ready. He doesn’t flinch away (he’s too obliging, too unquestioning, too accepting), but apologetically motions that he has his mouth full, insists upon chewing his food properly before swallowing. His kiss is successful despite himself, and when he retreats to the royal bed it isn’t for an act of consummation with his Queen but to curl up into a ball and go to sleep.

The very title of Soldier Man is a curious conjunction of roles and titles, and a syntactic separation of those two ideas of “soldier” and “man”. It’s a very charming film, and its lightness belies the oddness of Langdon’s persona. It’s not sentimental, which is a bonus, and allows Langdon the chance to wander innocently through at least two different genres of film. There is the war drama, which the film immediately removes all possibility of pomp or danger; and there is the Ruritanian drama, with its crowd and court and mistaken identities, which the film makes immediately absurd and parodic. It’s quietly radical, gently ironic. When Harry awakes, we wonder what the meaning of his dream might be. Does it have a meaning? It’s a fantasy in which the dreamer does nothing more than wander aimlessly, ignoring all possibility of heroism (in the war drama) or romance and power (in the Ruritanian drama). The dreamer wants nothing more than to continue sleeping. When he wakes, he seems as innocent of the real world as of his fantasy. Yes, indeed, this is a curious film. It makes me want to see more Harry Langdon…

After Langon’s short, we begin our main feature – and our last: Are Parents People? (1925; US; Malcom St. Clair). James Hazlitt (Adolphe Menjou) and Alita Hazlitt (Florence Vidor) are a married couple on the verge of divorce. Their daughter Lita has been called back from school to hear the news of the separation. Lita plots to find a way to “cure” her parents’ symptoms. At school, Lita’s roommate Aurella (Mary Beth Milford) has a crush on both the film star Maurice Mansfield (George Beranger) and on the local Dr Dacer, who is also the object of Lita’s affection. When Lita’s parents visit the school, each offers her a different vacation option – but she prefers to stay at home. When a teacher finds photos and letters to Maurice Mansfield, she accuses Lita of being the culprit – and plans to expel her. Mansfield is shooting a film nearby, and takes an interest in Lita – but she arrives home to discover she has been expelled. Lita pretends she is the culprit in order to ensure her parents have to meet and discuss her future. Mansfield is summoned to Alita, and he assures her he has never met Lita – and proceeds to flirt with Alita. Lita seeks refuge with Dacer, who doesn’t realize she is in his home until the early hours of the morning. When Lita returns to her parents the next day, arguments and accusations ensue. Lita seeks solace with Dacer, who is wooed by her charm, and the Hazlitts manage to reconcile their differences (at least for now). THE END.

Well, this was a diverting film. It has a simple setup, and it delivers a well-directed and well-played result. I always enjoy watching Adolphe Menjou, and his interactions with Florence Vidor – as the pair bicker, argue, flirt, joke, and reconcile – are both amusing and poignant. (Florence Vidor, by the way, was the wife of director King Vidor. Curiously enough, the pair had divorced shortly before the production of Are Parents People? One wonders quite how she felt filming such scenes.) As Lita, I found Betty Bronson very charming and engaging. But there is little depth in her character, just as Dacer – and Lawrence Gray’s performance – is a bit flat. Though George Beranger has fun parodying a pretentious film star, acting out a whole film and trying to seduce Alita, his character is likewise paper thin. And this rather sums up my reaction to Are Parents People?, which was restricted to being charmed. I cannot say that I was moved, nor that I laughed a great deal. It was all very… pleasant. In comparison with the only other Malcolm St Clair I’ve seen, A Woman of the World (1925), Are Parents People? seems rather tame and unremarkable.

That said, it is certainly fluently and sensitively directed. Though there are no really striking images, the drama plays out nicely through small details, especially some very good cross-cutting between the two parents. Their actions and reactions mirror each other, creating all kinds of subtle little parallels and contrasts. And much of this takes place without dialogue. The opening sequence is ten minutes of wordless action, through which we grasp the whole drama through glances and editing. When there is dialogue, it is often short and snappy – echoing the back-and-forth repartee of the editing. But St Clair isn’t Lubitsch, nor is this script one of any depth or lasting resonance. Its charm is only so charming, its amusements only so amusing. I’m glad I’ve seen it, but I suspect my memory of this film will quickly pale.

In terms of the presentation, it’s a shame that Are Parents People? survives only in a 16mm copy, which is very soft to look at. Though it is nicely tinted, the amazing pictorial quality of many of the films shown earlier at Pordenone (and even the other films in Day 8) show the gap in preservation status. If this is a visually downbeat way to end the online Pordenone, it is at least a reminder that so much of film history is lost to us, and what remains is precious. Music for the first three films of Day 8 was by Mauro Colombis, and for Are Parents People? by Neil Brand. The all-piano soundtrack here was very good, though I cannot but note that past editions of Pordenone online have ended with orchestral (or at least ensemble) scores. Combined with the lesser visual quality of the film, and my reservations about the film itself, it felt like a slightly limp way end to the festival. But hey, we can’t always end with a bang, and I’ve enjoyed so much already – so I shouldn’t complain.

My experience of Pordenone from afar in 2025 has, as ever, been absorbing and exhausting. There is no other festival that offers so much, and of such diversity. We’ve traversed the globe, and we’ve traversed the era. The emphasis is not on presenting masterpiece after masterpiece but about widening our appreciation of the silent era as a whole. In this, Pordenone is unique. Even the online material, which is but a tiny fraction of the festival offered on site in Italy, is a tremendous cross-section of people, places, themes, genres, and contexts. One can only be exceedingly grateful for so much marvellous, and so much entirely new, material. For a single ticket, the quality and variety of films Pordenone offers online is exceptionally good value. Bravo to all involved in this amazing festival.

Paul Cuff