Day 3 of Pordenone takes us to California Scotland, where we lurch into a melodrama of dastardly speculators and wronged women. (Brace yourselves, this makes for a chunky synopsis…)

The White Heather (1919; US; Maurice Tourneur). The speculator Lord Angus Cameron has lost his money and that of his friends in a stock exchange crisis. He journeys to Shetland Castle to visit his brother, the Duke of Shetland. The Duke lives with his sister Lady Janet and her son Alec McClintock, together with their housekeeper Marion Hume – whom Cameron has secretly married and with whom he has a son, Donald. When Cameron arrives and asks the Duke for £20,000, he is refused. The Duke doesn’t want the debt to pass to his family if Cameron dies without heirs. He recommends Cameron marry a rich woman of the right class, someone like their guest Hermione de Vaux. Meanwhile, both the gamekeeper Dick Beach and Alex are secretly in love with Marion. On a hunt, Alec gives Marion a spring of white heather for luck, while Cameron is warned about the legend of the “Devil’s Chimney”. During the hunt, Donald duly walks in its shadow and is wounded by a gunshot. In the aftermath, his identity revealed – and that of his parents. Denying he is the father, or that he is married, Cameron publicly refutes Marion. Marion writes to her father, James Hume, another speculator, who has fallen seriously ill. She reveals that the only record of her marriage was lost onboard the White Heather, the ship on which they married, and which sank soon after. The case goes to court, where Hume is threatened by Cameron. The only surviving witness, Captain Hudson, cannot be located. Dick promises to find Hudson, while Hume goes bankrupt – and collapses – searching for new resources to fund his lawsuit. While Marion endures hardship to support herself and the child, Dick finally locates Hudson, who reveals that the marriage records were sealed in a waterproof case when his ship sank. [Are you still with me, reader??!] But Hudson is in the pay of Cameron, who fears that divers will retrieve the records from the wreck before they have a chance to destroy it. He sets a gang of roughs on Dick, while heading to the wreck at Buckminster Reef, where divers are working on the foundations of a new lighthouse. Dick is wounded but survives to tell Marion and Alec of Cameron’s scheme. Both Cameron and Alec find descend to the wreck. In the fight on the seabed, Cameron accidentally cuts his own air supply and dies, leaving Alec free to find the case. On the surface, Dick dies of his wounds – but only after giving his blessing to Alec and Marion, who are now free to marry etc, etc, etc. FINIS.

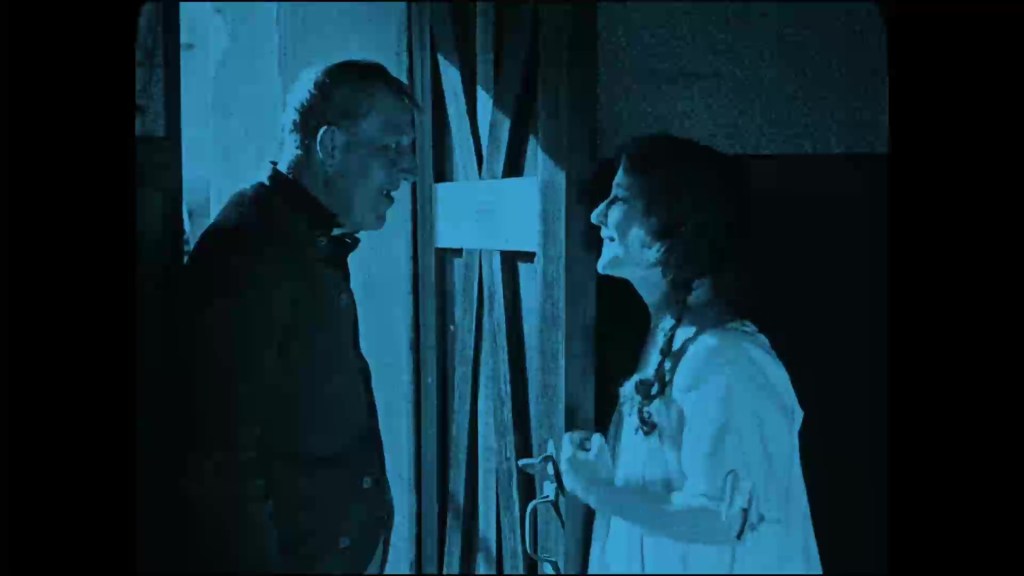

Lordy, lordy, lordy. Well, The White Heather is less than 70 minutes long, but it is crammed full of melodramatic incident. Indeed, that’s the trouble with it. So much time is spent advancing the plot that there is no time for a single character to develop anything resembling a personality. Much of the dialogue, indeed, consists of recapitulation and exposition. “Given that you have done this, Lord Shortbread, you shall inevitably encounter that!” “You swine, McCleft! Don’t you remember that you yourself did that, and in revenge I shall do this!” The characters are lifeless clichés, lifelessly mobilized. Doubtless some of the problem lies with the original play on which the film was based. The original Drury Lane production of 1897 was a bloated melodrama of four hours, designed expressly to show off impressive scenery – stock exchange, ballroom, castle, underwater wreck – and dramatic set pieces. In this, it shares something of the same pedigree as William Gillette’s Sherlock Holmes (1916). But whereas the Gillette film is lumbered with a great deal of unnecessary baggage from the stage version, Tourneur’s adaptation of The White Heather turns a bloated play into a very lean film. The production retains the central set pieces, using these to showcase its locations, set design, and photography. But despite its leanness, I found The White Heather almost unendurably banal.

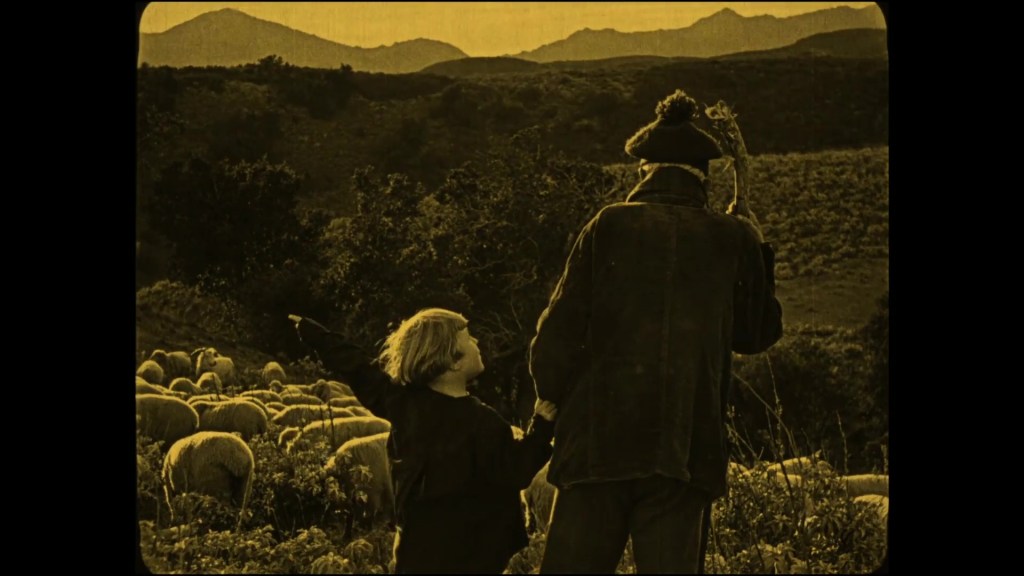

Though my brain went hungry, my eyes were given a feast. This is, after all, a film by Maurice Tourneur, photographed by René Guissart. As such, it is quite simply stunning to look at. Every frame of this film is almost unbelievably well composed, well lit, and well photographed. The interiors boast exquisite low-key lighting, wherein every detail is subtly and perfectly outlined with light in the midst of the gloom. The exteriors seem always to be shot at some magic hour, whereat the light saturates everything on screen. Whole sequences seem to exist just to show us how beautifully they can be lit and photographed. Take the sequence of shots – each its own perfect tableau – in which Dick searches for Hudson. The gloomy streets and interiors look amazing, simply amazing. There is one shot of people huddled in a doorway, the rain lashing down in a pool of light, which is one of the most individually striking shots I have seen in all the films shown via Pordenone so far. The exquisite green tone/yellow tint combination makes the shot even more perfect: just see how the textures of the wall, the sheen of the highlights, are all the more vivid. And the underwater climax, shot via a huge tank placed below the surface, is startlingly effective. This scene was the original play’s theatrical showstopper, so the film really needs to get its adapted equivalent right. And boy does it deliver. What could be (and surely is to a degree) an absurd dramatic situation needs to be saved by its realization, one that gives it some kind of reality, some kind of visible and tangible danger. Tourneur and Guissart manage to do just that, and however unbelievable the drama, one cannot but be sucked in by the photography. My god, this is a beautiful film.

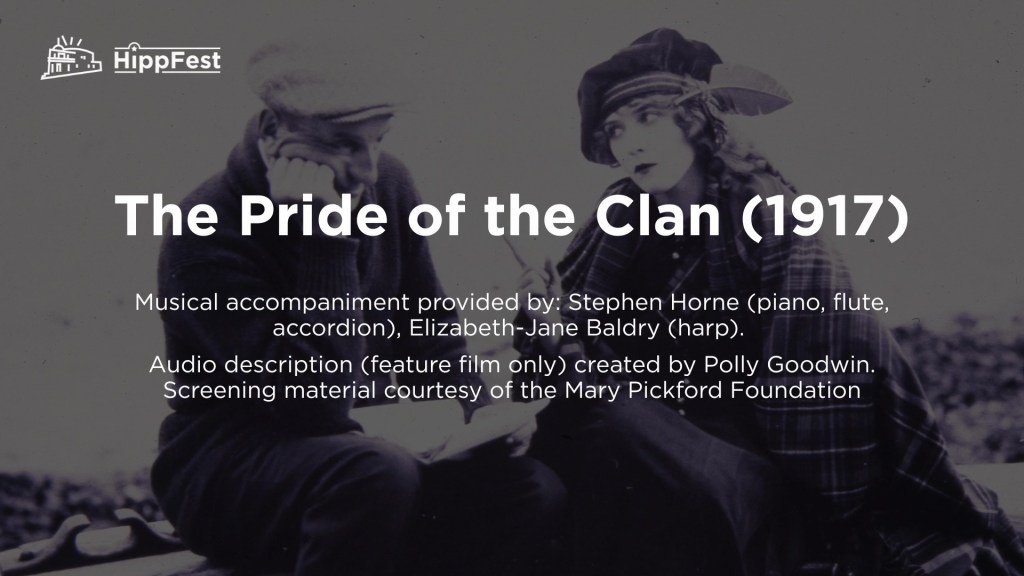

And yet, and yet, and yet… Somehow the sheer prettiness of it all only served to underline just how empty this film is as an emotional drama. It reminded me very much of Tourneur’s The Pride of the Clan (1917), which I saw in a beautiful restoration via HippFest at Home earlier this year. That, too, had a faux Scottish setting, beautifully lit and photographed – and was utterly inconsequential as a drama. But The Pride of the Clan at least had a sense of humour – and Mary Pickford. The White Heather has neither. The cast – H.E. Herbert as Cameron, Ben Alexander as Shetland, Ralph Graves as Alec, Mabel Ballin as Marion, John Gilbert as Dick, Gibson Gowland as Hudson – is uniformly fine. But they have literally nothing to work with or develop by way of character or personality. Of all the cast, Mabel Ballin is the most obviously sympathetic, and Gibson Gowland the most striking – if only for the instant visual reminder of his frightening physical presence in Greed (1924) a few years later. But these pleasures are fleeting and superficial. If my interest was piqued, it was by association with other films – not by the drama of The White Heather. So yes, a beautiful film, one of the most technically accomplished pieces of photographic work you could hope to find in 1919. But its pleasures are pictorial, not dramatic, psychological, or emotional.

I should also add that this restoration is based on the only surviving print, a Dutch copy with translated titles. The English titles have been restored on the basis of censor records, contemporary descriptions, and the text of the play on which the film was based. I must say that some of the titles look a little odd in relation to the surviving montage. (Early on, for example, a title relaying the Duke’s words to Cameron is inserted in the middle of an exchange on screen in which the Duke is looking and talking to his wife. Later in the film, words spoken by Cameron are inserted into a shot in which Hume is speaking. Are these really the correct moments for these titles? Each example might be where a Dutch title was inserted, but that doesn’t mean it’s the place where the original English text belongs.)

Finally, the music for this presentation was by Stephen Horne. This was chiefly for piano with occasional interventions by other instruments. It had more moments of interest than the film, though its obligations to match moments of “Scottishness” on screen (i.e. various pipers a-pipin’) sometimes exacerbated the silliness rather than mitigated it. But it was a sterling effort, capable of heightening the aesthetic pleasure of the images if not deepening their emotional power.

Paul Cuff