To begin, a confession: the Blu-ray of The Battles of Coronel and Falkland Islands has been sat on my shelf for ten years. Yes, ten years of being shuffled from house to house, from shelving unit to shelving unit. Ten years of being saved for tomorrow. Well, tomorrow has arrived – today! I’m not sure why the existence of the film and its convenient BFI home media edition slipped my mind for so long, nor why the notion of watching it suddenly popped back into my brain. But regardless of why, I have now watched it.

The Battles of Coronel and Falkland Islands was directed by Walter Summers for British Instructional Films (BIF), a company that made documentaries and features through the 1920s. Among their larger productions were a series of historical recreations of battles from the Great War. Alongside naval dramas like Zeebrugge (1924) and The Battles of Coronel and Falkland Islands were others about the western front like Ypres (1925), Mons (1926), and The Somme (1927). The Battles of Coronel and Falkland Islands is the only one of these films to be fully restored, though others are available via the BFI streaming service. Summers’s film is the flagship production (forgive the pun) among this series because of the scale of its recreation and because it has been seen as a companion piece to Sergei Eisenstein’s Battleship Potemkin (1925). I will discuss this more later, as the discourse around this comparison is almost more interesting than the act of comparing the films itself.

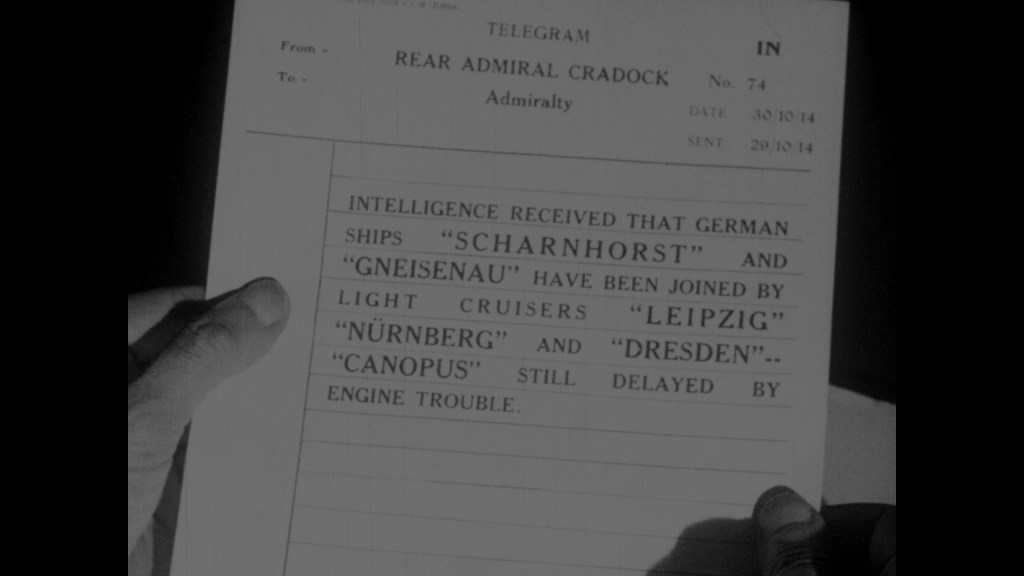

The Battles of Coronel and Falkland Islands is set in 1914 and recreates two successive battles in the Pacific and Atlantic, fought by British forces against the German fleet under Admiral Graf Maximilian von Spee. The Battle of Coronel, in November 1914, was a defeat for the outclassed British ships, during which the Germans lost three wounded against British losses of 1600 killed (and two ships sunk). The Battle of the Falklands, in December 1914, was a total reverse of fortunes: for only a handful of casualties, the British sunk four German ships – killing over 1800 men and capturing another 200. The opening narrational title of Summers’s film puts it this way: “This is the story of the Sea fights of Coronel and the Falkland Islands – of a victory, and a defeat as glorious as victory – a story of our Royal navy, which through storm and calm maintained for us the Freedom of the Seas.”

The tone of this summary is revealing. Yes, the credits thank the Royal Navy for their cooperation, and boast of the many resources put at the production’s disposal; but it is not just historical recreation, it is a depiction of “glory” and empire. Rather sweetly, the credits list which (historical) ships are played by which (real) ships of the Royal Navy. None of the human cast get mentioned, which epitomizes the balance between the recreational/historic aspects of the film and its dramatic/human aspect. For while Summers takes care to humanize the leading protagonists, especially the various commanders, it is in the naval operations themselves that the film is principally concerned – and best at handling.

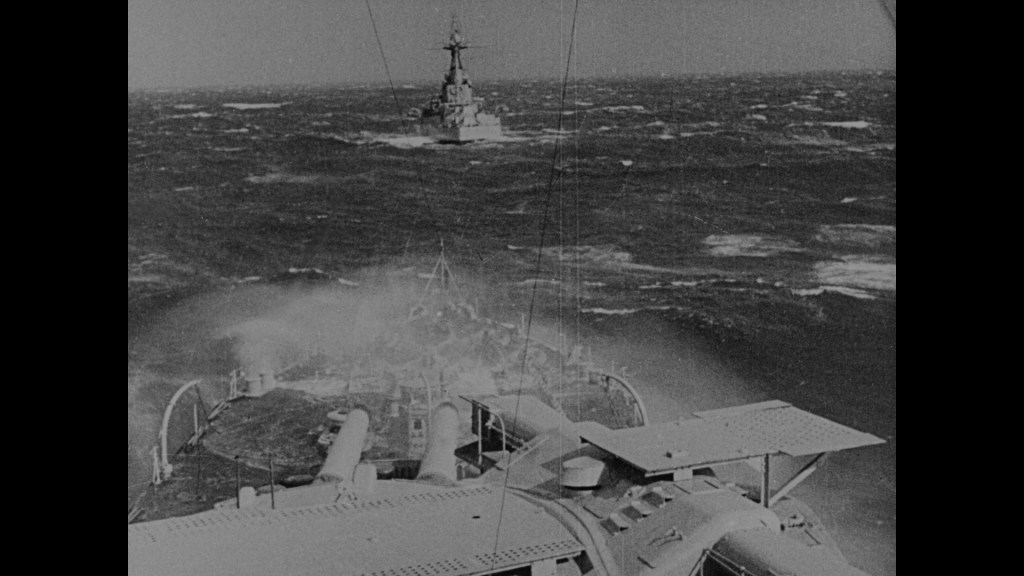

Here, he has an impressive array of ships and materiel to play with. Most obviously, he has several Royal Navy ships to film – from sea, from land, from high on deck, from the depths of the hold. He finds lots of interesting angles, though the commanders at their respective helms are always framed in the same way. In part this helps anchor the spaces, as well as draw parallels between the opposing commanders – all of whom are treated sympathetically.

Most impressive, however, is the sequence (called “The Effort”) in which the British prepare their ships to sail out to the Falklands to intercept the German fleet. There is a long montage (about seven minutes) of preparations. We see a dock’s worth of activity: moving equipment, welding iron, stockpiling ammunition, loading supplies. Since the crew is working day and night, there are some striking scenes in the dark of the activity illuminated by flashes of light. There is also a marvellous tracking crane shot, filmed (I presume) from one of the dock’s mobile platforms suspended over the loading bay. It’s a great shot and I wish there had been more moments of such camera movement. But Summers reserves one of his very few other mobile shots for a similar tracking shot that moves up the food-loaded expanse of von Spee’s victory banquet table in Valparaiso. This is one of the only moments in the entire film that struck me as a truly incisive, analytical use of camerawork, for it is not used simply to show-off space but to comment on the action. A contrast is being drawn between the parallel preparation of both sides: while the British are working night and day to rebuild their fleet, the Germans are feasting and drinking. It’s a nice touch, but noteworthy for the rarity of its… well, stylishness. It’s the move of a dramatic director rather than a documentary reconstructionist.

Indeed, I am tempted to say that Summers is better at directing objects, and cutting between spaces, than he is at directing people. His choreography of the various crowd scenes is quite repetitive: too often, everyone on screen is doing exactly the same thing. Thus when the militia at Port Stanley spot the German navy approaching, they all go to the cliff edge and they all point at it. When the Royal Navy closes in on the disabled German vessels at the end of the film, the curious crew all go to the railing, and they all point at the vessels. Summers is a bit better in the action scenes, with crews rushing around or dying. But even here, at the end of the battle, when the Gneisenau is scuttled, there is a shot of the German crew all gathered in various degrees of stiff, unnatural poses. (Really, what are those gestures supposed to be? Are they mimicking Mr Muscle?)

Beyond the crowds of sailors, Summers also tries to humanize his set pieces by having little vignettes of individuals or pairs among the crew. Thus, we see HMS Canopus being painted by a comic sailor who gets paint on his comrade; or we overhear conversations of sailors in-between or just after bits of action, making comic asides. I say, “comic”, but what I really mean is “tedious”. The performances are stiff, the rhythm is slow, the supposedly colloquial dialogue clunky and contrived. I suspect the humour may have gone down better in Britain in 1927 but suffice it to say that a century later these scenes do not work. (Thinking back, I recall similar scenes in Powell and Pressburger’s naval war drama The Battle of the River Plate (1956), which are likewise cringeworthy efforts to show jolly working-class sailor folk maintaining their plucky British spirits.)

All of which brings me back to the comparison with Battleship Potemkin. There are striking parallels and striking contrasts. Both films alternate between drama on land and sea, depicting history as a kind of spectacle. But while both films don’t have characters so much as collective groups, there is a vast difference in its attitude toward hierarchy. Summers has a great respect for officers of both sides – they are all represented in strikingly similar ways, with an emphasis on calmness, stoicism, and honour. This is a striking contrast to the sadistic, violent officers and priests of Battleship Potemkin. Summers is very much invested in the class system as embodied in military ranks. Eisenstein is interested in revolution, Summers in the maintenance of class and Empire.

In this sense, Summers’s film is as implicitly propagandistic as Eisenstein’s is explicitly so. The Battles of Coronel and Falkland Islands is a defence of British imperialism: the film begins and ends with references to the defence and glory of Empire, with Britain as the guardian (if not the owner) of the “seven seas”. But Summers is also careful not to dehumanize, let alone demonize, his enemy. Though there are plenty of sneering, triumphalist looks among the German officers, Spee himself is a very sympathetic (one might also say tragic) figure. He refuses to gloat or condemn the British at the victory feast, and his acceptance of the bouquet is tinged with a self-conscious defeatism: Spee says the flowers must be kept in case they should prove useful at his own funeral. (Summers makes sure to show Spee brooding on them later in the film, as defeat looms.) The film clearly admires stoicism and bravery on both sides: the suicidal courage and flag-waving defiance of the British ships in the opening battle are echoed in the actions of the doomed German crews in the second battle. There is nothing like this in Eisenstein’s depiction of the tsarist military of any rank in Battleship Potemkin.

In terms of naval spectacle, Summers’s film boasts greater resources. While Eisenstein makes do with what is clearly a single docked ship, Summers has a small fleet that is clearly filmed at sea. The scenes in which the refitted ships set sail to the Falklands are excellent and I wish there had been more scenes like this. Summers seems very concise, which is to say limited, in his use of this footage. He does not explore the interior of the ships in much detail (a cabin, a canteen, a galley), and the upper deck is likewise limited to a small number of set-ups (a couple of gun positions, the bridge). What is missing is the sense of a ship as a lived-in space, occupied by a real crew. I wonder if it was either difficult or even prohibited to show too much detail onboard the Royal Navy vessels. (I wish he had used more mobile camerawork to explore these spaces. Apart from one very brief tracking shot in the canteen when action stations are called, the camera remains static.) Nor does his montage, or his image-making, ever quite produce a true sense of drama. (The best sequence is one of preparation, not of action.) Not only does Summers explain what’s about to happen in his narrational titles, but I always feel that he is at one remove from the reality being depicted. For all its recreational efforts, you feel that The Battles of Coronel and Falkland Islands is ultimately history in the past tense. Battleship Potemkin has a far greater sense of events happening before your eyes, disorienting you, sometimes terrifying you. And, it should go without saying, Summers does not have Eisenstein’s extraordinary eye for composition, for sudden bursts of impactful imagery – nor for his playful subversiveness. The Battles of Coronel and Falkland Islands is very effectively composed and edited, but I suspect that I will struggle to remember its imagery. But with each shot of Battleship Potemkin, Eisenstein seems to smack you round the head – every image is gripping, dramatic, dynamic. (Even the slogan-like text of the titles is punchily effective.) For all Summers’s resources and skill, and for all the similarities between these films, Battleship Potemkin is in a different league than The Battles of Coronel and Falkland Islands.

On this theme, I find myself thinking about the first time I heard of The Battles of Coronel and Falkland Islands. This was a reference and clip in Mathew Sweet’s feature documentary Silent Britain (BBC Four, 2007). I have very mixed feelings about this documentary. On the plus side, it offers a valuable trove of clips from a host of interesting films, many of which are still not publicly available. On the downside, the tone of Sweet’s narration is sneeringly dismissive of anyone who has ever dared to doubt the glory of British cinema in this period.

When I first saw Silent Britain in 2007, I felt that the countless digs at “some historians” was aimed (at least in part) at Kevin Brownlow, whose episode on British cinema in Cinema Europe (1995) (“Lost Opportunity”) offered a very sober account of this same period and subject. Comparing the two documentaries, it’s striking how many of the films and historic interviews used by Brownlow are also used by Sweeney. But Sweeney doesn’t discuss the struggles of the British film industry, nor reflect on the fact that many of the films he cites from the late 1920s were not only influenced by continental filmmakers but directed by them. Brownlow’s focus, as the title of Cinema Europe indicates, is to offer a wider perspective on the relationship between national cinemas across Europe – and to highlight their successes and struggles to compete with Hollywood. As such, Brownlow’s is a more complex project than simply rediscovery – although it is also one of the great documentaries on (re)discovering silent cinema. This is not to say that Sweet is wrong to champion the films he chooses (they are too little seen), but that he offers an incredibly one-sided interpretation of the period. Watching it again, nearly twenty years later, I find Sweet’s endless sniping about critics and historians incredibly irritating. (I sincerely hope that I never strike my readers this way.) The content of the documentary is superb, but the tone of the narration is too much like tabloid journalism.

In addressing (and criticizing) the Film Society (1925-39), where otherwise rare or censored films were shown to paid subscribers, Sweet mentions Battleship Potemkin and The Battles of Coronel and Falkland Islands together:

Everyone at the Film Society was astounded by the technique of Eisenstein’s film, but it wasn’t really so far removed from what a director called Walter Summers was doing closer to home. […] For all Summers’s ambition in a field we would now call “drama documentary”, this film would have been passed over by the Film Society. It was certainly given a rough ride by the cinema intellectuals writing in the influential magazine Close Up. Close Up’s critics wrote gushy fan letters to foreign directors while dismissing the work of British filmmakers as third-rate and uninspired.

Well, excuse me! I’d forgotten how snide Sweet was in addressing one of the most important English-language film publications of the period, and their wide-ranging efforts to engage with and analyse foreign cinema. I’m well aware of the reputation of Close Up as a hotbed of snobbishness, not to mention sexual experimentation, and I know some people who have little time for their writers and editors as a whole. But I can only roll my eyes at Sweet’s setting up of these straw figures to knock down with such contemptuous ease. The point of the Film Society was not to show big commercial hits like The Battles of Coronel and Falkland Islands, a film that was readily accessible in cinemas across the land, but films that were otherwise censored, cut, or prohibited. This inevitably meant an emphasis on foreign films and those of the avant-garde. And as for the way Sweet sneers at the notion of “cinema intellectuals” and their continental tastes…

Anyway, noting that Sweet didn’t bother quoting what Close Up actually wrote about Summers’s film, I bothered to look it up. The review (“The War from more angles”, from October 1927) is written by Bryher, one of the most interesting figures in British modernism of the interwar years. (I could write much on Bryher, but this is not the space…) Bryher states at the outset that she doesn’t think The Battles of Coronel and Falkland Islands is a bad film, but she does take issue with its tone – and that of similar recreations of the Great War. “The trouble is not so much what they represent as the way they represent it”, she says. “What I and many others (according to reviews) object to in the Somme [the BIF film of 1927] and the Battle of The Falklands is that war is presented entirely from a romantic boy-adventure book angle, divorced from everyday emotions”. Sensitive to the growth of fascism across Europe in the late 1920s, Bryher worries that “the ‘We Want War’ crowd psychology may destroy a nation” – and that films ought not to encourage it:

By all means let us have war films. Only let us have war straight and as it is; mainly disease and discomfort, almost always destructive […] in its effects. Let us get away from this nursery formula that to be in uniform is to be a hero; that brutality and waste are not to be condemned, provided they are disguised in flags, medals and cheering.

For Bryher, The Battles of Coronel and Falkland Islands repeated a trend common to other BIF films: “there was not a single suggestion that war was anything other than an elaborate and permissible adventure; or that there were thousands of men and women whose lives were broken and whose homes were destroyed.” She then offers her own vision of what a more sensitive film might convey, conjuring a kind of impressionistic montage in prose. In Summers’s film, the Scilly Isles stand in for the Falklands, and Bryher uses this as a springboard for her own memories of the war there:

[N]o gigantic spectacle is needed but a central theme worked out perhaps in a little outpost and related to the actual experience of people during those awful, hungry years. Scilly for instance (as I saw it in 1917) with the long black lines of the food convoy in the distance. A liner beached in the Sound with a hole as large as a room where a torpedo had hit it; the gun on its deck trained seawards in case a submarine dodged the patrol. Old men watching on the cliffs. An old fisherman rowing in slowly with a cask of brandy—wreckage—towing behind his boat and a smuggler’s smile on his lips. (How he must have enjoyed bringing it in legitimately in broad daylight.) Shipwrecked sailors from a torpedoed boat stumbling up the beach. Letters: —“If the petrol shortage continues it is doubtful how long the country can hold out” and down at the wharf the motor launches letting the petrol hose drip into the water because, between filling tanks, they were too bored to turn it off. The war as it affected just one family. Rations, rumours, remoteness. A film could be made of trifling impressions seen through the eyes of any average person. It would be valuable alike as picture and as document. But this glorification of terrible disaster is frankly a retrogression into the infantile idea of warfare, as a kind of sand castle on a beach where toy soldiers are set up, knocked down, and packed up in a pail in readiness for the next morning.

Bryher also contrasts BIF productions with The Big Parade (1925), which she sees as a far more honest depiction of war – and the dangerous lure of false notions of what war is. In the BIF films, war is “[h]eroic and nicely tidied up”, “[p]leasant to watch but completely unreal”:

There are plenty of guns and even corpses in the British pictures but the psychological effect of warfare is blotted away; men shoot and walk and make jokes in the best boy’s annual tradition and that some drop in a heap doesn’t seem to matter because one feels that in a moment the whistle will sound and they will all jump up again; a sensation one never had for a minute in The Big Parade.

Bryher praises the extensive dock montage sequence in The Battles of Coronel and Falkland Islands precisely because it was more honest:

Here the director touched reality, and the different machines, the darkness, the hurrying feet, and the long yard gave a feeling of preparation and activity that marked a great advance on anything previously seen in an English film. That was authentic England. Dirty and full of noise and right. The men were working the right way. Directly the atmosphere of the picture changed and the attention held.

To return to the comparison with Battleship Potemkin, it’s worth noting that Bryher never mentions Eisenstein in her review of Summers’s film: the British censors had banned it from being exhibited in the UK and it was only shown by the Film Society in November 1929. She places The Battles of Coronel and Falkland Islands in the context of other contemporary war films, especially those by BIF. Bryher sees it as part of a genre, and criticizes it as such. For all Sweet’s outlandishness, I can’t help but take his comment (I can’t call it an argument) that Battleship Potemkin “wasn’t really so far removed” from The Battles of Coronel and Falkland Islands as quite a cautious statement. Even he knows it’s absurd to claim it as a work equal cinematic, let alone cultural or historic, significance. Claiming it as “not really so far removed” is about as far as one might reasonably push it, though even here I would say that this is a gross simplification. As Bryher suggests, it’s not a matter of setting but of tone and style that distinguishes the BIF films from films like The Big Parade or Battleship Potemkin. The essays in the BFI booklet that accompanies the Blu-ray of The Battles of Coronel and Falkland Islands are rather more balanced than Sweet, arguing that it is a great film within its particular context. Bryony Dixon says that the dockyard montage is surely “one of the best pieces of filmmaking in British cinema” (Bryher says something similar), though she is also careful to shield the film from the kind of outlandish comparison that Sweet is keen to make.

Finally, a word on the score for the 2014 restoration of The Battles of Coronel and Falkland Islands. This was written by Simon Dobson and performed by the Band of the Royal Marines, together with the strings of the Elysian Quartet. Dobson uses the brass, winds, and percussion of the Band to create a marvellous sonic world – it has a great variety of rhythm, texture, and tone. I was curious to hear the way the strings are used to underscore certain parts of the film. They sounded to my ears more like the way a synthesizer is sometimes used to create a kind of acoustic wash beneath a dominant rhythm. The liner notes to the Blu-ray reveal that these strings were recorded separately from the Band and later mixed in to the soundtrack. This perhaps helps explain my sense of their slightly artificial placement. This is not a complaint, however, as the effect is certainly novel on my ear – and the whole score must rank as one of the more interesting and imaginative uses of orchestration that I’ve heard for a silent film. It sounds both akin to its period and genre, as well as sounding original. A perfect balance, and an enjoyable soundscape.

After going through the above, I feel some nagging sense of guilt that I should do more homework. Sweet’s complaint about most historians not being as familiar with British silent cinema as with foreign productions is surely true of me, if not others. In terms of availability, the situation Sweet observed in 2007 is rather better in 2025, but many important British silents are still maddeningly difficult to see. Half of the BFI’s “10 Great British Silent Films” (compiled in 2021) are not available either on DVD/Blu-ray or on the institute’s streaming service (and the DVD for Hindle Wakes (1927) is long out of print). And this list, of course, is but a tiny selection. Nevertheless, can we start by getting releases of The Lure of Crooning Water (1920) and The First Born (1928)? In the meantime, I promise to do my patriotic duty and watch not one, not two, but all three available British Instructional Films on the BFI Player service. None of this continental muck for me, just good ol’ British fare. (But after that, can I please resume writing “gushy fan letters to foreign directors”?)

Paul Cuff