To start off the new year, I’m doing something a little different. At the end of August 2024, I watched the streamed content of the Stummfilmtage Bonn. In the wake of my series of posts, I was contacted by Oliver Hanley, the co-curator of the festival. He wrote to answer the question I posed about the legal limitations of streaming, and his response encouraged me to ask more questions. Oliver was kind enough to have a longer conversation with me, the transcript of which is the basis of the three pieces that I will post across this week. We spoke about his background, his work at Bonn and Bologna, and about the difficulties and pleasures of curating a silent film festival. In this first part, we talk about Oliver’s route into curatorship…

Paul Cuff: I want to start with a quite basic question. How did you get involved in festivals and programming, and did you always have an interest in silent cinema in particular?

Oliver Hanley: We have to go a bit back to answer that question. I’ve always been interested in things from the past, from before my time. I think I first got into silent film through comedy, the big names like Chaplin and Keaton, etc. Then from there, I somehow progressed to German expressionism. I’m not entirely sure if that came from an interest in German culture or it was the other way around.

PC: Were you aware of silent cinema in broader culture when you were growing up?

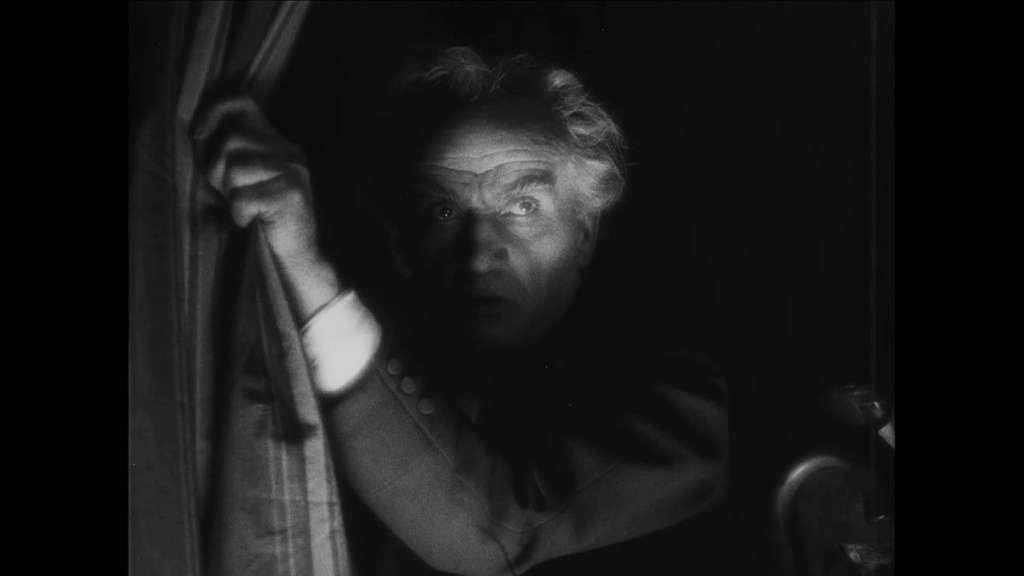

OH: Being born in the mid-1980s and growing up in the UK, I was fortunate enough to catch the last of the Channel 4 silents on UK television. I remember the first one I watched was The Phantom of the Opera [1925/1929] in 1995. And then they brought out Nosferatu [1922] the following year with the James Bernard score. I was lucky to see these films when I was reaching my late teens, which also corresponded with more and more silent films being available on DVD in decent quality. For example, I’d already known Metropolis from truly, truly awful VHS copies, so when I got a chance to see the (then) most recent restoration [from 2001], it was really a revelation for me.

PC: And at what point did you realize that you wanted to become actively involved with film culture?

OH: It was clear I wanted to devote my professional life to cinema. Naïvely, I initially wanted to be a filmmaker and thought I would become rich and famous. And either through ignorance or lack of good advice, I came to the conclusion that if you wanted to be a filmmaker, you need to do film studies! That’s how I ended up in Canterbury at the University of Kent doing the film studies programme there.

PC: Did experiences at university shape your ideas about a career?

OH: It was a combination of different factors. In the first instance, I didn’t have a good experience in the practical courses that I was doing. They put me off that for life. Second was that I volunteered at the campus cinema, which gave me the opportunity to see films there for free. They would show a lot of the BFI touring packages, for example new prints of Visconti and Fellini films, and a big Michael Powell season on the occasion of the centenary of his birth. But I was quite surprised that I would very rarely see my fellow film studies students at the repertory screenings. They would all go to see the contemporary art house stuff that was all the rage at the time. Films like Donnie Darko and Mulholland Dr. would be quite well attended, but not older stuff. I remember sitting in this empty theatre, watching masterpieces in beautiful prints, and wondering why no one was there. I really thought that this was a shame.

PC: Did you experience any silent films through these kinds of screenings?

OH: No, there was very little silent programming. But I had a very sympathetic lecturer on one of the courses who was also passionate about silent cinema. At this point in time, my main outlet for exploring silent cinema was DVD, and I would collect them like mad.

PC: Did this also give you an interest in the archival side of things?

OH: Yes, I read and watched a lot about how complicated it can be to restore film. I loved the idea of scouring the whole world and tracking down all the different elements and putting them together. I was fascinated by what Robert A. Harris did for Lawrence of Arabia, for example, and by what Photoplay Productions was doing for silent films. That was really what I wanted to do. But there was always that element of wanting to do it so that people would actually see the final result. Like you, I was at the screening of Napoléon [1927] in the Royal Festival Hall in December 2004. That was really, really something!

PC: After your undergraduate degree, what did you decide to do?

OH: All these early experiences shifted my focus towards wanting to devote myself more to making sure that the film heritage – especially the silent film heritage – would survive. It was the lecturer at the university who pushed me to do what was then the relatively new specialist course at the University of Amsterdam: the professional masters in Preservation and Presentation of the Moving Image. This was my stepping stone to continental Europe. I had said that I really wanted to focus on German film and asked if there would be a way I could do an internship or some unpaid volunteer work at a film archive somewhere. She recommended me to do the masters programme instead, because that’s where people will be sought after. I can’t necessarily say that this was exactly how it turned out, because jobs in this field are few and far between. Certainly, it’s an advantage to have this kind of background, but you still have to fight. Every year there are new graduates on the market, and the market is always getting smaller.

PC: If Amsterdam was your stepping stone, where did you go from there?

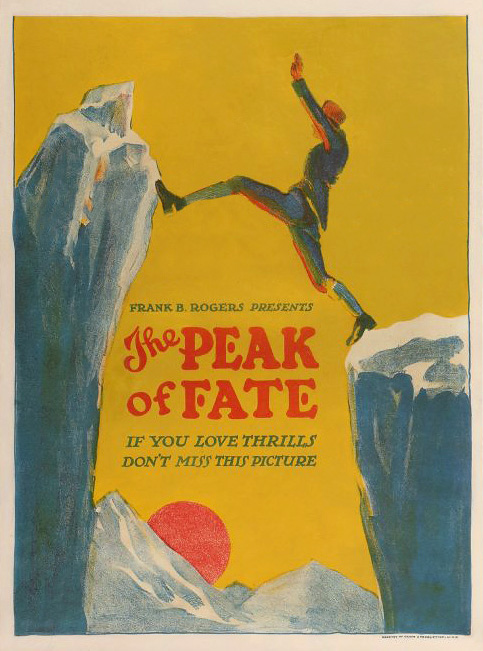

OH: Via the Amsterdam programme I ended up interning in Frankfurt at the Deutsches Filminstitut and helped with various tasks in the film archive, including a restoration project, and various contributions to DVD editions. What was important for me was that it changed my perspective. Before, I had been what you might call very canon-oriented: Lang, Murnau etc. This is all great, but my experience in Frankfurt opened my eyes to what was beyond the canon. I learned to appreciate the unknown, what film history really has to offer. At this point, I changed tack and started questioning why we are so focussed on the classics, when there is all this great other stuff around. This is something that continues to influence me in my work right up to this day, for example in our Bonn programming. Particularly with German films, we try to push the lesser-known works rather than the big names. This can also tie in with the restorations being done by certain institutions.

PC: Did your time at the Deutsches Filminstitut encourage you towards curatorship?

OH: Actually, I wanted to go more into the technical side of things and do laboratory training. This didn’t work out, which I think was for the best because I’m not really a technician. I understand a lot of the technical processes and have been quite fortunate to get into the scene before analogue was being phased out. When I started, digital technology was up and coming in the archival and restoration fields, but no archive could really afford it. The big studios were going digital, but no one else. Now it’s completely different. At the time, I gained background experience with analogue, which is good because I think it’s important to know both.

PC: If you didn’t end up going into laboratory work, where did you want to go?

OH: After graduating from my Masters studies, I moved to Berlin and managed to get on board a project at the Deutsche Kinemathek. I came expecting to stay only three months – and ended up staying three years, moving from project to project wherever there was funding and work needing doing, but my dream was to become a film restorer. Back then,I think my idea of a film restorer was still Kevin Brownlow, who is actually more of a historian who restores films. But that is still what interests me most about the process: the research, comparing different versions, putting together what might be a representative edition of a film. When it moves into the technical procedure, I’m a bit more hands off. Obviously, I supervise the grading and transfer etc, but the most exciting part is over for me.

PC: After your experiences in Germany, you went to Vienna. How did that happen?

OH: At that time, there was very little money for film restoration in Germany. In 2011, I got an offer to start working at the Film Museum in Vienna. I was brought in to take over the task of curating their DVD series, which was something that had always fascinated me. DVDs had been my gateway to the film heritage, and I loved watching the extras. So, the Vienna job was a dream come true. But I also helped build up the museum’s streaming presence. We had very, very limited means, so we were looking to see how to get parts of the collection online without it costing any money. For example, we digitized newsreels that had been transferred to U-matic video tape in the 1980s. You didn’t have to worry about it being 4K or anything like that, it was just a case of dusting off our old U-matic tape player to get these films transferred and put online for the sake of access.

PC: Did you envision doing this kind of work permanently?

OH: I was more and more keen on getting into the restoration process. The museum had a complete digital post-production workflow in house. It was very small, very artisan level – we were just doing a couple of projects each year. But it enabled me to become more involved in selecting some of the films or supervising projects at a managerial level. The museum had quite an interesting collection of nitrate prints of obscure German silents, but the films didn’t really fit the museum’s curatorial profile. (They have a very strong connection to the avant-garde experimental film scene, to Soviet cinema, to American independent cinema, and so on.) Nevertheless, we were able to do some very cool projects at that time, including one with funding from the World Cinema Project, and some of these restorations then ended up on the DVDs I was producing. At the same time, whenever I could, I would investigate their nitrate collection. But it was difficult for the museum itself to restore this material. By this period, around 2015-16, money was finally being made available in Germany to digitize the German film heritage.

PC: So there more opportunity for the kind of work you wanted to do in Germany?

OH: I was in Vienna for five years. By the end of my time there, I had reached a point where I had done everything that I could with the means that were available. I was worried that I was just going to start repeating myself. But in 2016, I got the offer to come to work at the Film University in Babelsberg, where I still live, just outside of Berlin and home to the famous film studio. The Film University – Germany’s oldest film school – had set up a heritage programme at the end of 2015, modelled somewhat on the one I had taken in Amsterdam, and I was brought in to teach at Babelsberg in 2016.

PC: After all your experiences in archives and museums, was it strange going back to teaching?

OH: I felt like a change. And years of being involved with practical work, I felt – in an idealistic way – that I was returning to teach the next generation. I was able to bring my experience into teaching, but also my network that I had built up over many years.

PC: How did your earlier experiences shape your teaching?

OH: In the first instance, we did visits to archives and yearly excursions to Il Cinema Ritrovato in Bologna. But I also got some wonderful people in the industry to come to us and do guest lectures: Jay Weissberg, who runs the Pordenone Silent Film Festival, for example.

PC: It sounds like a very rewarding combination!

OH: Of course, working for the university also had its less glamorous side, and there were several administrative duties. I did the website, the newsletter, and so on. But you had a lot of freedom and a lot of access to resources, especially for academic events and various collaborations. We have our own film museum here, Filmmuseum Potsdam, with its own cinema, and we would regularly do events together. These were linked to my classes, so it was a requirement for students to attend.

PC: What kind of events were these?

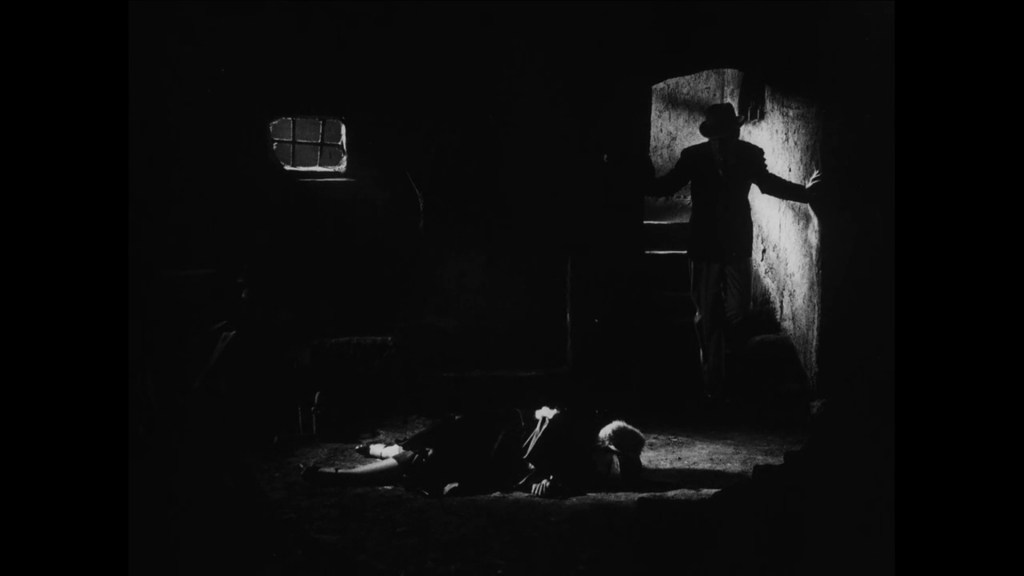

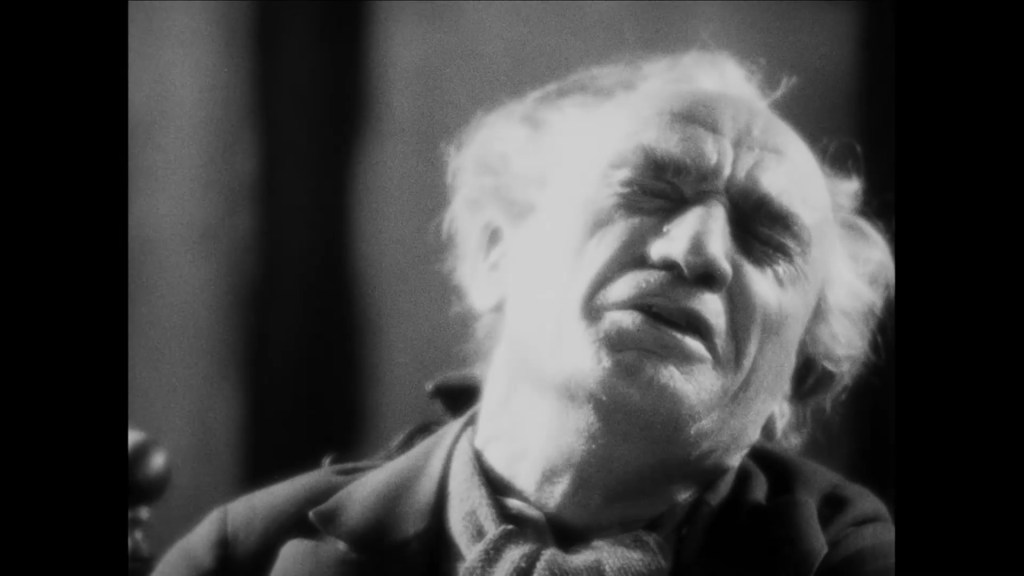

OH: In my case, it was almost always a silent film event. I would get the funding through the “ZeM”, the Brandenburg Centre for Media Studies, and that would cover the cost to do a silent film screening with live music, and a guest speaker who would then do a lecture during the day. The first such event we did was Das Cabinet des Dr. Caligari [1920]. We brought over the restorer, Anke Wilkening, to talk about her work on the film, and Olaf Brill, a German film historian. Brill’s book about the film, Der Caligari Komplex [2012], does an amazing job using primary written sources to try to quash the legends that had built up over time, and to reconstruct who was responsible for what during the writing and production. Yes, the film is a German classic, we’ve seen it a million times, and we all think we know it inside out. But both his research and her restoration enabled us in different ways to see the film in a completely new light. That was kind of the focus, and every second semester we would repeat this concept as much we could.

PC: What other events stick out for you?

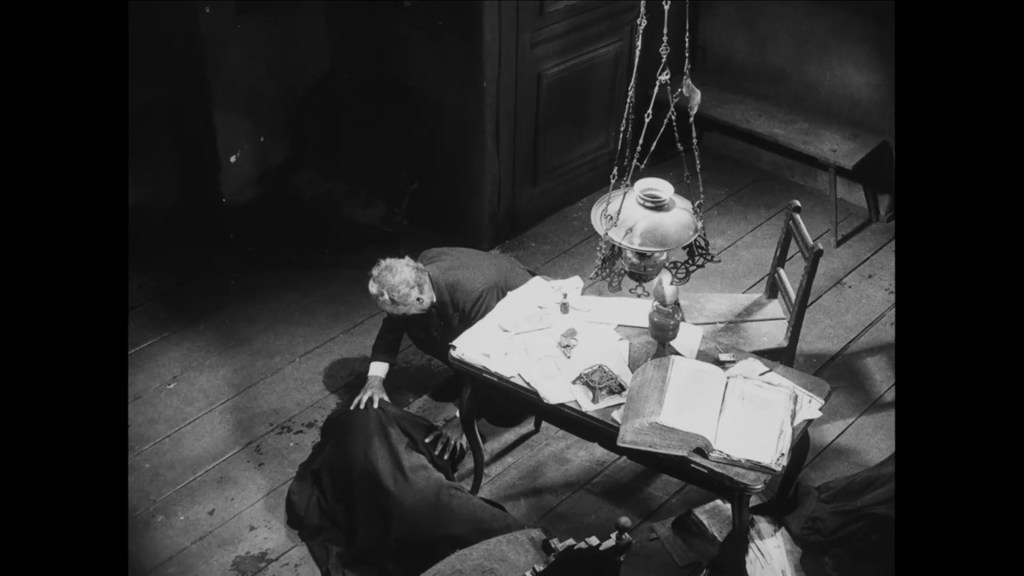

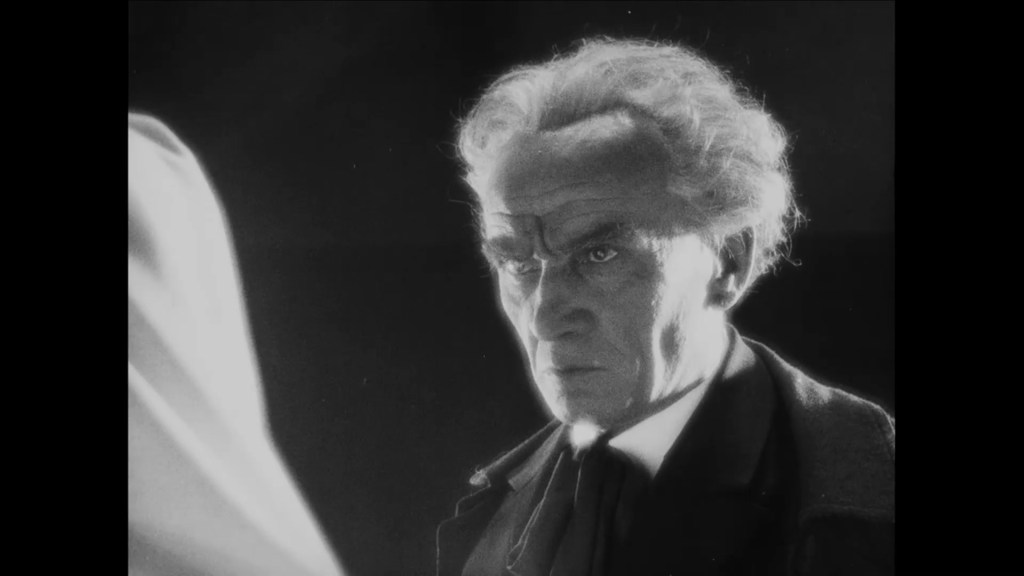

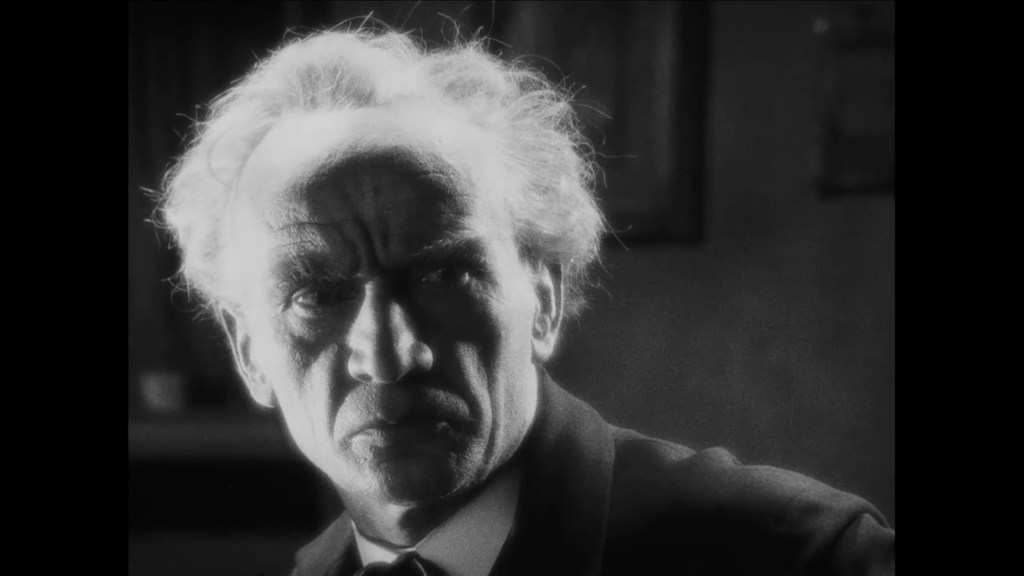

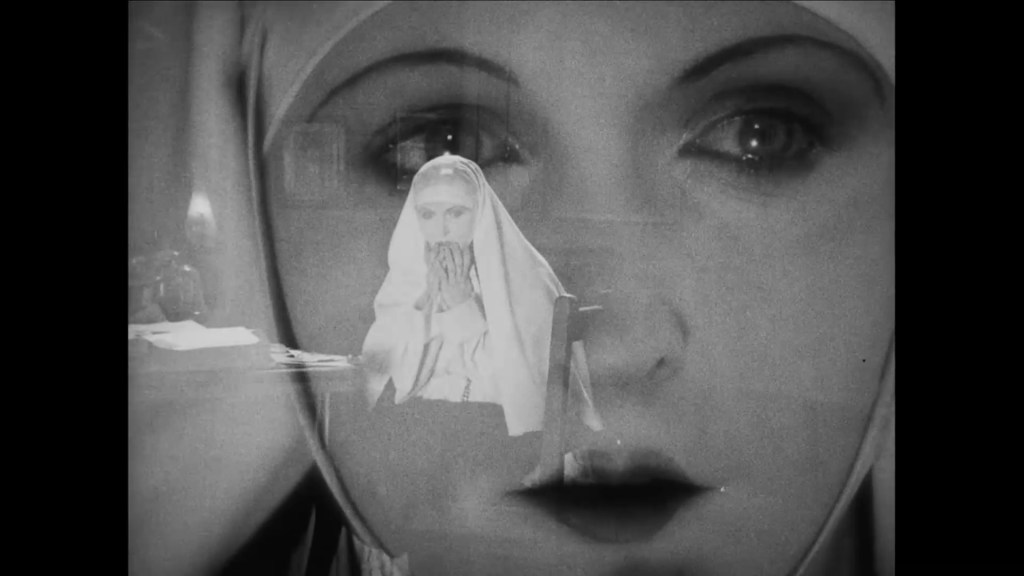

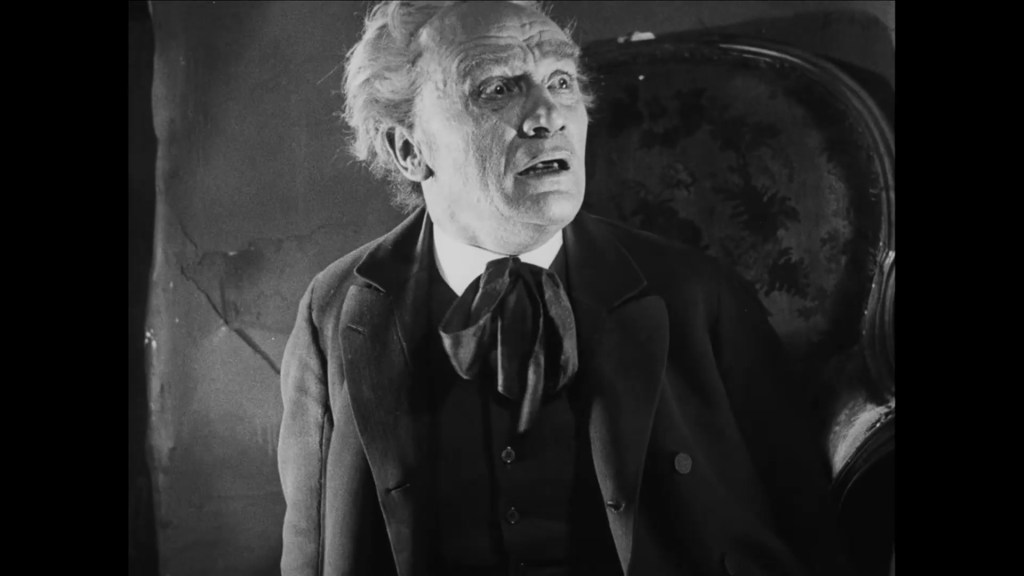

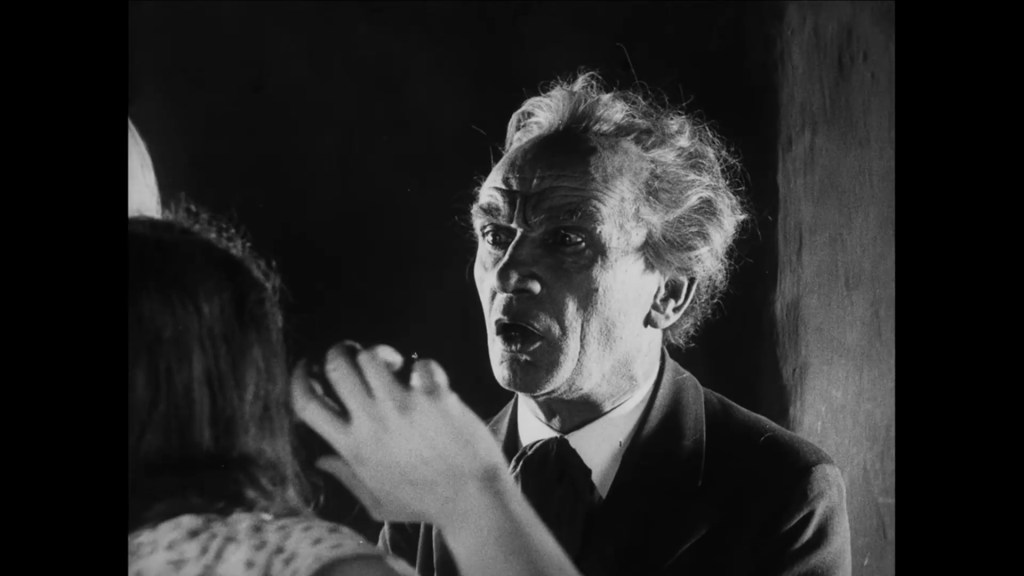

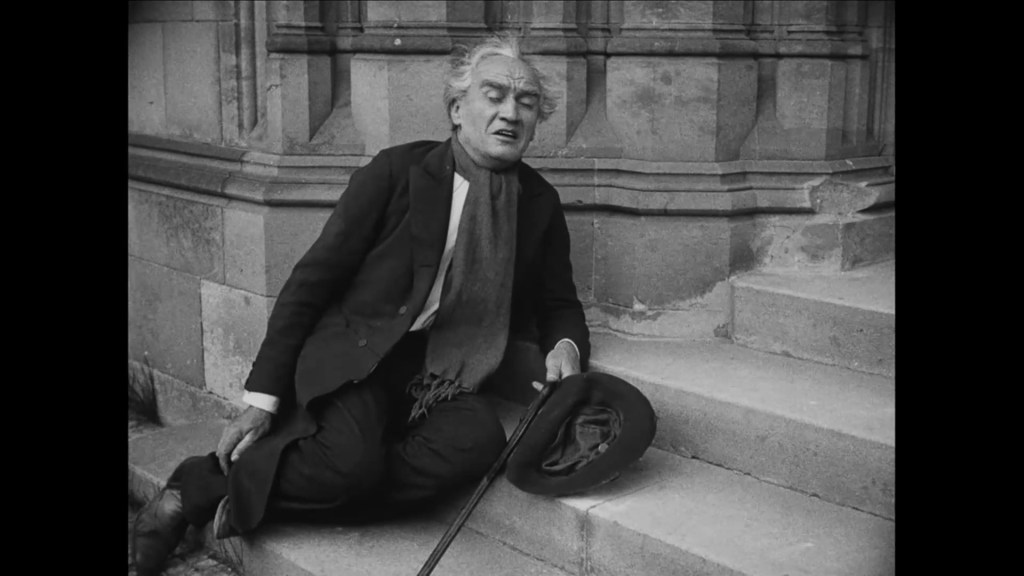

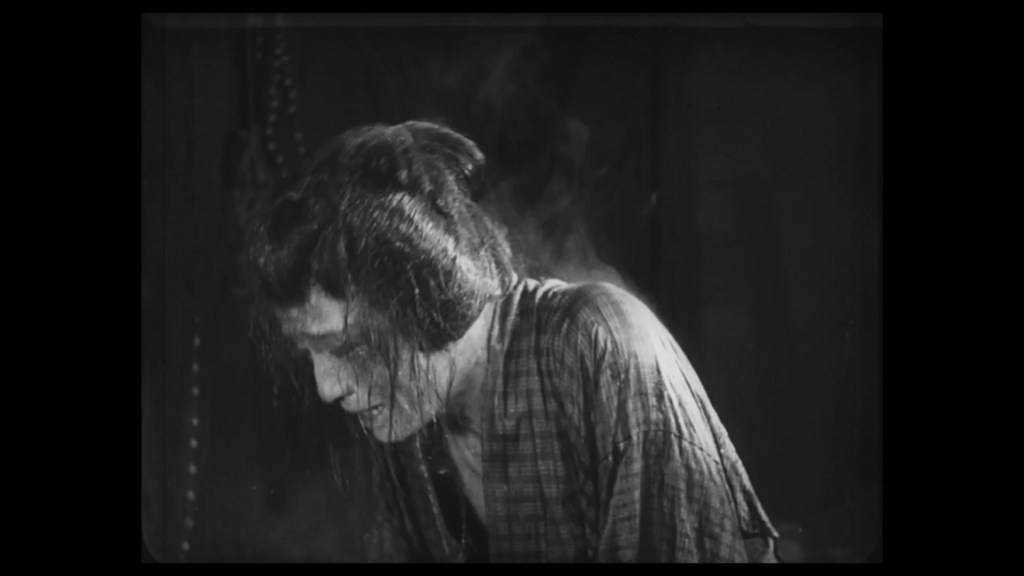

OH: The year after Dr Caligari, we did Der Golem [1920]. This was a curious case because two different institutions in Germany, the Friedrich-Wilhelm-Murnau-Stiftung and the Filmmuseum München, were doing two different restorations concurrently. But that was extremely interesting because the two restorations followed completely different concepts. Filmmuseum München’s restoration benefitted from the major discovery of the film’s original score by Hans Landsberger. Landsberger only did four film scores, and I think all of them were at that time considered lost. But Richard Siedhoff, a silent film accompanist over here, came across the score for Der Golem in a German archive (seemingly no-one had thought to look before!). It wasn’t the complete orchestral score, but a reduced conductor’s score that Siedhoff then re-orchestrated. This version was shown recently on German television.

PC: How did you try to use archival material – familiar or otherwise – to engage your students with film history?

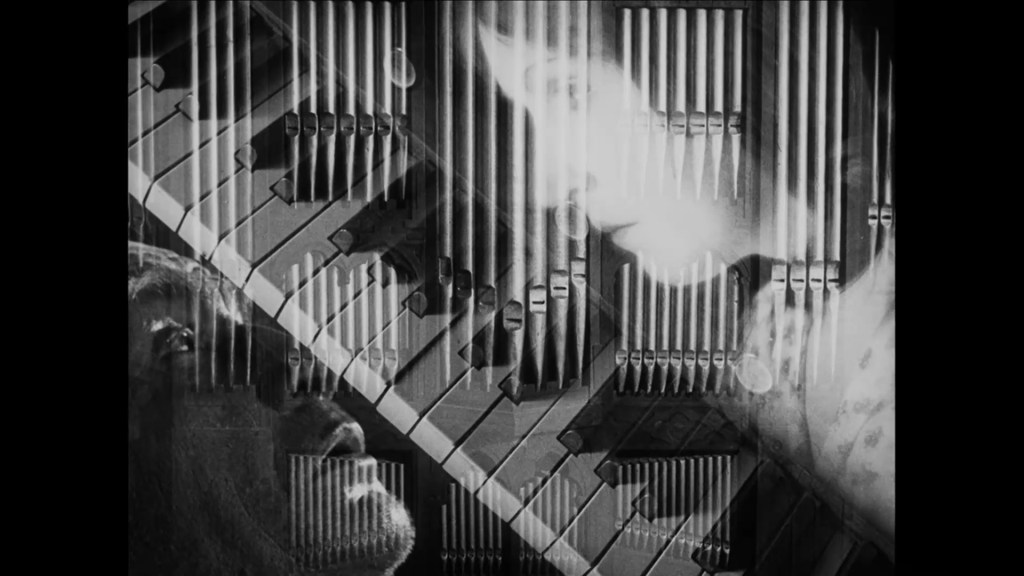

OH: Just before Covid hit, we did our biggest event – a series of lectures and screenings in about five parts. It took a completely alternative approach to the idea of the canon. We’re completely oversaturated with these “definitive” restorations, so I wanted us to look at the (by now) lesser known and – in some cases – quite bizarre re-release versions of German silent classics from different periods in German history. For example, we showed Die zwölfte Stunde [1930], which is a re-release of Nosferatu essentially as a sound film. The soundtrack doesn’t survive, but the rest of the film remains complete. We showed this version because it contains interesting changes, including some extended sequences with footage that was shot for the re-release. When you watch it as a silent film – and we showed it with live music – it can be a bit weird, but it still works. Something else we showed was from 1932-33, the crossover from the Weimar Republic to Nazi Germany. At this time, they re-released the first part of Die Nibelungen [1924] with a soundtrack. The significant thing about that soundtrack is that Gottfried Huppertz, who did the original score for Nibelungen, for Metropolis [1927], and for Zur Chronik von Grieshuus [1925], personally rearranged and conducted the recorded version for the re-release. The other interesting thing about it is that it was created not as a precursor to what was going to happen in Germany, but to mark the fiftieth anniversary of the death of Wagner. And so Huppertz incorporated Wagner’s themes into his original composition. It’s a bit of a mix of Wagner and Huppertz, but it’s a fascinating document.

PC: How easy was it to get hold of prints of these non-canonical versions?

OH: We had to put a lot of effort into screening Die Nibelungen because there’s no screenable print available of the 1932-33 version. The FWMS had done a preservation on film, but they had not made a screenable print. But we convinced them to send the preservation negative to our university to be scanned (since we were working for a state-of-the-art film school, naturally we had our own film scanner!). From the raw scan files, I then prepared the digital version for our little screening, knowing that it wasn’t restored – or even graded properly – but at least we could see the film this way. We also showed Die weiße Hölle vom Piz Palü [1929] in its “talkie” re-release version of 1935.

PC: What about more recent re-releases? Did they feature in this series?

OH: Yes. There was this company called Atlas in the 1960s that began by distributing art house films in Germany (Bergman, Antonioni, etc.). But they also re-released old films and they did a series of silent films in the mid-1960s with synchronized scores. We showed one of these because they’re very of their time, especially with the music. There is a version of Dr Mabuse [1922] with music by Konrad Elfers, from 1964, which you could imagine being a score to a kind of Euro James Bond rip-off! We also showed a television version of Dr Caligari from the 1970s with a score by Karl-Ernst Sasse, a very well-known composer who scored a lot of DEFA films, among other things. Inevitably, we crowned the series with Giorgio Moroder’s Metropolis [1984], which – I must admit – is a guilty pleasure of mine. And not just mine, it seems, as there wasn’t an empty seat in the house!

PC: Did organizing this series influence what you subsequently did at festivals?

OH: In my professional career, I had always straddled the preservation and access side of archival work, but up until this point I had mainly focused on providing access through digital media, DVDs, online. When I started doing these live cinema screening events, it was the shape of things to come for me, because it’s more or less what I do now with the festivals. I still have one foot in the preservation side of things, because I supervise a limited number of digital restorations. It’s good to be on both sides of the process.

PC: Do you think you would always have ended up as a programmer of films for festivals?

OH: In a way, I think it’s very logical that I’ve ended up where I am. From that early experience in the university cinema, right the way through to Bonn and Bologna – it’s all been about getting films to people. It was a long time before I got to where I am now. What’s the famous phrase? It took me fifteen years to become an overnight success! But I’ve been very fortunate.