This week’s piece is in tribute to the composer and conductor Carl Davis (1936-2023), who passed away last week at the age of eighty-six. Like so many, it was through Davis’s music that I fell in love with silent cinema. I first saw Napoléon (1927) in a live performance with his score in December 2004. It was an experience that changed the course of my life. Seeking out other silent films meant encountering more of his music, especially the Thames Silents series, for which he composed many extraordinary orchestral scores. In all, he wrote music for nearly sixty silent films—from the shorts of Chaplin and Keaton to the epic features of D.W. Griffith and Abel Gance. This body of work is of inestimable importance in the revival of silent film and live cinema.

These last few days, I have been wondering how best to pay tribute to Davis and his music. But where do I even begin? Faced with such a challenge, my solution is to focus on one experience of one work. Thanks to Carl and his daughter Jessie, I was able to attend some of the recording sessions for Napoléon in September-October 2015 at Angel Studios, London. What follows is a transcription of notes I took during these sessions. Some of these notes informed an article I wrote on the relationship between live performance and recorded soundtracks. But anyone who has written a piece for academic (indeed, any kind of) publication knows that translating an aesthetic experience into prose inevitably sacrifices much of what was essential to that experience. Just as I have never—despite trying on innumerable occasions, out loud and in print—adequately described the impact of seeing Napoléon, so I feel I have never done justice to how thrilling and moving is Davis’s score for the film. His music understands Gance’s film, grasps and articulates the essence of it, in a way that no other has ever done. It follows that the vast majority of what I wrote during the recording sessions in 2015 has never found the chance to be “translated” for publication. I reproduce them here in their original form because I cannot conceive of where else they might find a reader other than myself. If nothing else, they summon the spirit of the recording sessions.

You will see that I have not tried to attach names to all the snippets of conversations and instructions going on in the booth. This is partly because I couldn’t always identify where the words came from, partly because I didn’t know the names of everyone in the studio, and partly because I like to keep fidelity to my original style. Thus, you will see that I keep referring to the recording producer as “the captain”, since the booth looked like the helm of a ship. (In fact, his name is Chris Egan.) In terms of form, my original transcription kept the line breaks of the manuscript, but for the sake of space here I have indicated line breaks with “/”. I regret this a little, as the line breaks at least gave an impression of the continual shift of sounds and images that I was trying to capture on the fly. Limitations of form aside, I hope this piece gives you a sense of the recording sessions—of the communal effort, the humour and generosity of Davis and the Philharmonia musicians, the skill and perfectionism of Chris Egan and his production team. It was a tremendous privilege to sit, watch, and listen to this wonderful group of people make music. Reading my notes again after several years, I am reminded of all the hours I have spent under the spell of Davis’s scores—and that these hours have been some of the happiest of my life.

Friday, 25 September 2015

A small, narrow passage; below, a pit that has been extracted from somewhere familiar. / A forest of leafless music stands, petrified. / A flautist is playing “Ça ira”—badly (I’m sure they will improve). / Double-bass sarcophagi, garish and plastered with the remnants of official approval. / The control room has a triptych of glass: Polyvision for the captain at this land-bound helm. / The way out (for relief of at least three kinds) is through a warren of panelled attic doors, over duct-taped zigzags like sloughed snakeskin… We go up, along, left, up, left, down, around, through, up, along, and across (we come back a different way). / An intertitle awaits us in the booth: “In this feverish reaction of life against death, a thirst for joy had seized the whole of France. In the space of a few days, 644 balls took place over the tombs of the victims of the Terror. (Hist.)”

The forest is drawing a population, perhaps curious by this new landmass lifted from an extinct theatre. Warblings, farpings, shrill snatches of melody—broken, repetitive, working towards fluency. The musicians settle. / A titled mirror on the far right; behind, two fragments of wall and window snapped from the upper deck of this ship. / The title is replaced by a murky image, a square of potential floating within the dark grey frame of the monitor. (A gown is waiting to flutter, flickering faintly with the quiver of an electric pulse.) / The clamour of sound grows. / Latecomers, carrying instrumental coffins. (The inhabitants are beautifully preserved.) / The atonal buzz aids my prose—this is an attempt to reacquaint myself with pen and paper.

The players cannot see the film; only the captain and the conductor. / Davis is at the mirrored helm opposite our enclosed triptych cabin. / The forest is filled with music—overlaid, overlaid, overlaid, overlaid. / Superimposition of sound is joined by strange, deep exhalations, breaths short and rasping, the scatter of conversation.

The timbre of Davis’s voice cuts through a multiplicity of clarinets: “This is a transcription of a Beethoven piano sonata, hence all the fiddly bits.” / The sonata is now sonorous. / The captain wanders the helm. / Sound explodes against the triptych glass and breaks into the booth through multiple speakers, bouncing around—wind hitting receptive sails. / A conversation between helm and pit. / Strings only: the balance shifts, hisses, stops. / The speakers on the left and right are shrouded in a black veil, as if in mourning. / In the helm, the music has passed into sound—made indirect. / The woodwind are in the central window of the triptych through which I gaze, yet their music emerges from a speaker on my left. / The timpanist is lost in the funeral roll and misses the calls to stop. He looks over his shoulder at us, nervously.

Though the man stands straight before me, Davis’s voice comes from my left and hovers above a hum of voices behind the black shroud. / Davis’s arms are the only mobile branches.

“Short! Short! Apart from that last note…” / The woodwind give the strings an appreciative noise after their run-through. / Davis amends the balance between bassoons, clarinets, and oboes.

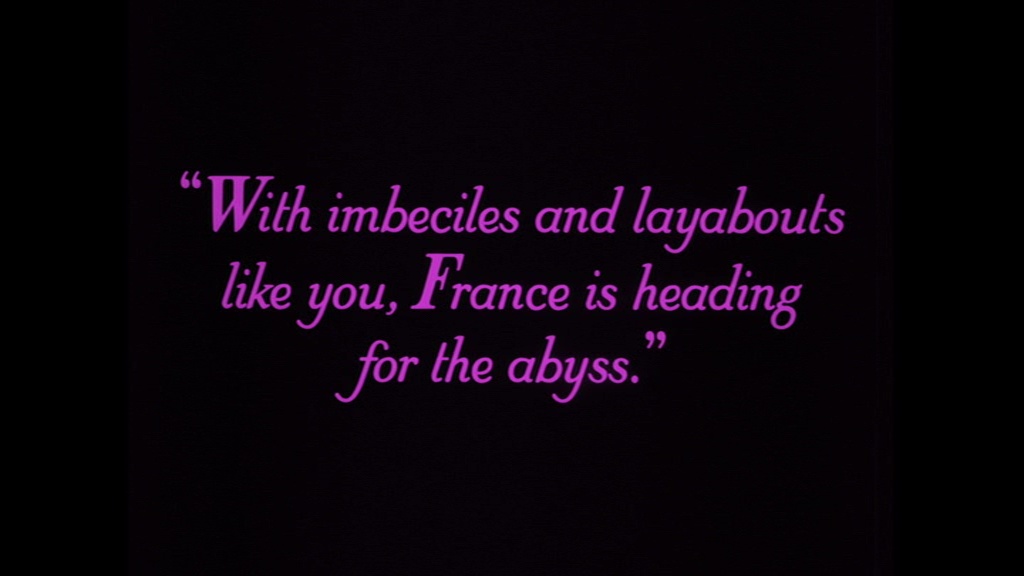

Describing the prison scene the players cannot see, Davis explains: “This is all tragedy and despair and fainting and… so on! It’s meant to be heartrending!” He laughs. / The helm sends instructions: “Six quaver clicks to bar one…” and Josephine enters her cell. / A vertical blue stripe gleaming like cobalt glides across an intertitle and a large white circle leaps into the centre of the frame. Napoléon has been bombed by Ballet Mécanique.

Salicetti enters the room, but the music stops—he carries on into Bonaparte’s cell in awkward silence before someone orders him to freeze; he stays wrapped in his cloak, glaring at the man he has yet to reach.

Clarinet One speaks: “I need some more click.” / A voice from behind me in the booth: “In other words, what you’re saying is ‘Carl, conduct in time’!” / “Yeah, something like that.” / Before each take the musicians put on headphones in ritualistic accord. / Josephine looks out of her cell window outside; Davis wipes away an invisible shot; Gance cuts to the exterior; Davis wipes away another image; Gance cuts back to Josephine.

Salicetti steps into the room once more; he makes it two steps further before being ordered to freeze; he looks even crosser, hands on hips, his glare wider under the foaming plumage of his hat. / “Sorry to stop you. The room was a little bit noisy. Please be careful of noise in the room”, the captain stresses with polite firmness. / “The trombones are moving…” The culprits of the noise? Eyes peer suspiciously round the corner. / Two monitors (one above, centre; one below, right) display the interrupted scene. We are waiting in 2015 and they are waiting in 1927.

The orchestra has lost its click track. / “You may have lost the clicks, but we’ve still got them.” / “I doubt it, on the basis that our computer froze entirely.” / “OK. It’s just my delusional state.”

[Later]

“Folks, just to let you know that I need you to be careful of noise in the quiet moments in this passage, particularly bars 8-11 and 17-20. I’m getting a lot of noise in the room.” / Another take. / “I’m going to need you to go again with that section straight away.” / “9 and 10 are still vulnerable. Strings, if I could suggest that you keep your instruments up when you’re not playing—that would really help us.” / “6 clicks into bar 51…” / Salicetti tries again—and fails.

“Have I got a wipe at this point?” / “Yeah, and I’ll give you a streaker.” / Davis: “OK, this should be ferocious.” / Salicetti enters the room: the orchestra roars in unison before giving Salicetti’s steps the fierce momentum of his mood. / Salicetti enters again, even more ferocious (he’s been frustrated before). / Captain: “Coming from where we’ve been, we really need to make a statement of intent. If we can have a strong accent on that first note, that would help us out of the last cue.” / “Yup”, agrees Davis, “Drama.” / The orchestra hits the silence with even greater force.

Davis: “It’s very serious, I’d say. Dark. A very sonorous sound. And the trudge, trudge, trudge of the bassoons.” / Salicetti confronts Bonaparte. After all this time (so many times, in fact), Bonaparte ignores him—“I’m working out a route to the east, by way of a canal at Suez”—and Salicetti slopes out.

The players are requested to check their mobile phones. There is a rustle of amused outrage. Davis extracts his phone. It was the maestro! / Captain: “OK, I’ll gloss over that.” / Davis: “Napoleon was very modern!”

Basses and cellos are intense, wringing darks strains of melody—opposite, a first violin. / “Some people are landing late on 45. One more time please folks, and please be careful of noise.” / Another take. / “Fabulous. Just a small repair. I’ll give you 4 clicks on 45. Just a little intonation thing, I’m sure we can fix it.” / The third monitor (above, right) mutely tracks the number of takes, moving from “Next” (green) to “Current” (red).

Absolute silence: the helm has muted the orchestra, even their conversation. / “OK, I’ll have the room back on please.” / “We’ll give you a red streamer at the cut-off.” / A whole scene is played through. Davis’s gestures strike the invisible cuts that have changes in emphasis. / Afterwards, the captain double-checks the list of errors with his assistant. A series of repairs are needed, named as timecodes and bars. / “I’m just not covered with a few little noise things for 16-17.” / A series of instructions are relayed from helm to pit, channelled into every player’s ears. Bar-by-bar orders. / “Still think we can do 33-36 better.” / “Anything else, Chris?” / “Yeah, just 57 to the end—general untidiness.” / They go again. / “A little more from the bass drum, please. Carl, if you could pre-empt the streamer.” / It goes wrong. / “Actually, if we could do from 55 through to the end, that would make our join much easier.” / The strings leave.

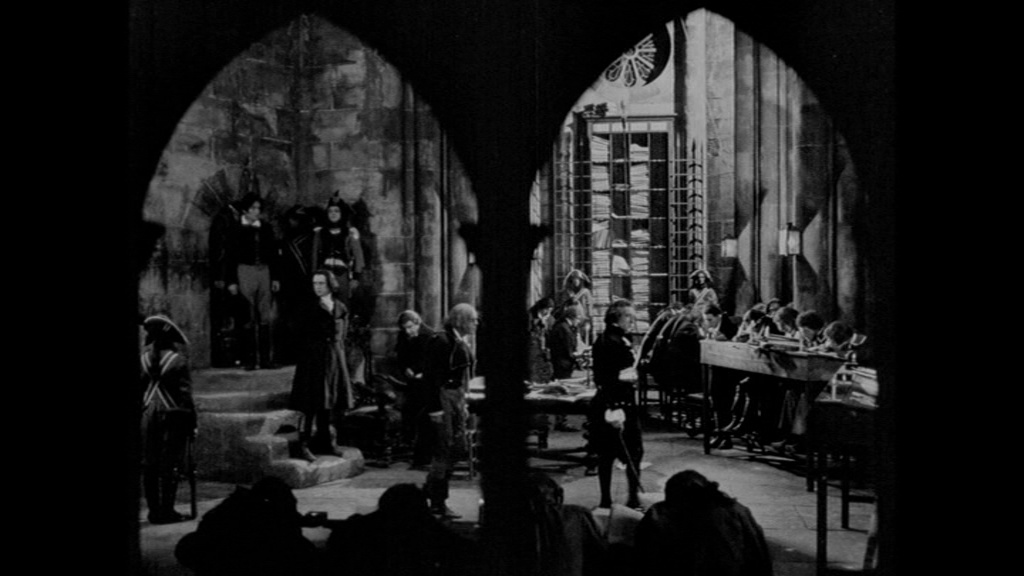

Bach’s Passacaglia in C minor. / Davis tells the woodwinds to be sinister. / Abel Gance enters the room. He is oblivious to the dots and streamers that flick and slide across the digital image. He observes the form of the guillotine in the paperwork. The contrabassoon is guttural. A look of lugubrious pleasure glows in Saint-Just’s expression. The winds growl, the double-bass is scraping the pit of a cavern, and the gothic arch above Saint-Just vibrates with shadow.

“The ending was fabulous.” / “The end was fabulous? Uh-oh!” / “No, no! I just meant the last phrase was perfect.” / They begin. They stop. / “Sorry folks. A little noise in the room.” / Davis: “Yeah, a little distracted. OK, now a minute-and-a-half of glory.” / The bridge of the double-basses resembles the gothic arch of the scene. / Time for coffee.

[Later]

A new session, post caffeine. / The audience awaits—on the screen, and the second screen—a thousand faces face the camera. / Minor wrath at those in the orchestra who have not yet put on their headphones. / Minor panic that a flautist is sitting in the cor anglais’ seat.

Four minutes through which Bach is unwound and ravelled anew—a fearsome logic works itself into a crescendo of volume. The floor trembles, the seats tremble. I feel the music crawling through my flesh, sounding out my bones, testing my tendons.

It is evident that someone has ignored instructions. The booth comments: “That’s how we know who was wearing headphones.” / “Do you want us to land more heavily on that second note?” / “Yup. It’s like—urgh!” (Davis mimes being strangled to clarify his answer for the player.) “OK, so this is nasty, I would say. This pizzicato…” He describes his intentions to the strings, then turns to the whole ensemble. “OK everybody: implacable. We are implacable.” / Amused accusations and counter-accusations when orders for a silent downbeat are missed by one player. / “One of the horns?” Davis inquires. Laughter. “What do I know! I’ve got headphones on.”

Again. / “Can we stop there please, Carl. Sorry folks. It took a few bars to settle. I think we can do it better than that.” / Again. / Deep breaths. / “Bravo, brass.” / Bar-by-bar analysis from the helm. / “Good. Well… not good!” / “No, but will be.” / “It will be!” / Davis delights over some phrases: “The arrangers have drawn out this lovely detail—I think we can really make something of it.” / “One more time folks, thank you. I’m not fully covered yet. It’s sounding fabulous—but we need to make sure it’s absolutely right.” / A repeat. A break.

“Carl?” A voice from the orchestra. Davis looks around. “Over here—the horns, Carl.” / The horns want to have another go. / The captain enters the conversation, addressing horn player Nigel by name. / Another run. Saint-Just despises his body once more, his final speech is about to go again. / “I almost have it. I think we just need to really attack it, picture-wise. If we really attack it hard, we can do it just once.” / Again the floor shakes, the wall shakes. / It works. / “What now?” / “I’d say a 30-second break.”

“I’m thinking something strenuous.” / “Exactly. We’ll have a look and see.” / Discussion. “It’s the Coriolan Overture. The real fun with this is that I had to remove the big major chords in here. It’s a clumsy cut, but necessary: the good news hasn’t come yet! You’ll see when they come.” / A pause. We go back in time before Saint-Just begins his speech. / “The Philharmonia playing Coriolan. How marvellous”, Davis enthuses. He marshals the players.

Robespierre now takes the stand. He is drowned out in the orchestra of voices on screen and by the voices of the orchestra in the pit. / A complete run-through. / Davis discusses the accent of the two-note phrase with the lead violin. / More stitches, revisions. / More, more, more.

A break for several sections. They gratefully remove their headphones and scratch their heads. / Cellos, double-basses, and bass-drum execute a run of tuttis in pizzicato. Their notes walk across the room in single-file, surrounded by stillness and silence.

[Later]

The afternoon session. / Violin is being prepped for recording. Her scenes are timecoded, broken down, divided-up. The beats will fall in the right places—and the orchestra will fall into step. / Davis explains his choice of quotation. As the orchestra can’t see the film, he also describes the action.

The beat precedes the players. They land in its midst and fall into step. / Run-through whole cue. / Changing trills from A-flat to A. “It’s nastier”, Davis concludes. / Another take. / Discussion of dynamics for strings. The helm believes all “to go up one… Everything needs to be a bit healthier.” / Davis compliments his players: “I love the crescendo-diminuendo. It was a real treat.”

Click track adjustment. / Timecodes changed to give an extra second before a key change. / Complex instrument-swapping. / The tambour militaire is changed.

“Follow the click.” / One of the woodwinds went too early and points it out: “I came too early.” / “Yes, you did. I was a bit bewildered”, responds Davis. “I thought, ‘Did I write that?’” Laughter. / More discussion. / “Beethoven’s a terrific film composer”, comments Davis.

There are more small screens in the pit: mobile phones with metronome apps, ticking in silence but synchronizing with the headphone click-track. / Noise of instruments being picked up. / Many takes of Bonaparte entering the Convention: the horns must redo one section; the strings are getting tired; the fifth retake produces laughter… / “Don’t worry”, the helm tells the players, “Whatever we do next will be easier. We’ll find something. There must be something easy in the remaining four-and-a-half hours of music.”

In the hiatus, the woodwind break into a rendition of “Ça ira”, as if threatening revolt against the helm. / Davis responds to the woodwind: “Play it as if it’s familiar to you.” The “Ça ira” becomes more fluent with repetition, as does the other traditional French song, the “Chant du départ”. “Play it knowing that everyone in France knows it”, Davis adds.

It’s the Bal des Victimes. / “Shall we follow you at the click?” / The click sustains the score when soloists are absent. Josephine plays the piano without a pianist. The rest of the orchestra plays around her in silence. / Solos. / “Carl, just don’t turn the page. There’s nothing more I can offer you to help.”

[Later]

The hurdy-gurdy player is alone with Davis in an empty pit. / Davis mimics Robespierre’s hand gestures on screen. / Many takes. Nervous atmosphere.

Monday, 29 September 2015

I have waited in the street outside. I walked past the studio boss on the way, grateful for my sunglasses. / The side road was populated by isolated groups of musicians, smoking or eating. / I am almost recognized. / I want a giant badge that says I belong here. The one face that I wear by default announces only uncertain hesitation. / There are new faces in the orchestra. Old comrades greet each other. The clarinettist from Friday is gone. The grumpy viola returns (only just in time). / The speakers in the helm isolate individual microphones. We hear the sound of drums, horns, strings, woodwind. Each springs into the aural spotlight, its comrades falling into artificial distance.

The Victims’ Ball again. First run-through (without click).

The film frame has slipped—it always will at this timecode. Its perfection is not needed here, not yet. / The snare drum needs a higher pitch. (“We’re being dragged down.”) / Davis instructs individual players on the purpose of phrases: “This is Napoleon spoiling the fun, the old party-pooper.” / The timing is perfect.

The film frame has slipped—it always will at this timecode. / The revellers enjoy another take, and spring once more into joyful dance. / Whilst the dancers step and swing in immaculate gaiety, the orchestra is still settling into cohesion.

The film frame has slipped – it always will at this timecode. / Snare or tambour militaire? “Let’s have both”, Davis says. “It is for Napoleon, after all.” / Rhythm is adjusted from 89 to 95. Figures are tapped into machines, electric notation reconfigures itself.

The film frame has slipped—it always will at this timecode. / Fourth take. An oboist makes a last joke with his colleague. She laughs quietly with only a click to go. The clarinettist scratches his ear as the other sections replay their parts.

New cue. / “It’s supposed to be light and frothy!” Davis explains. He breaks into giggles just as he counts the players in. / The clarinet fluffs his solo. General bemused consternation. / “That was frothy alright! It took us all by surprise. It was fun while it lasted.” / A long pause and discussion. Another take. The drummer is reading a novel. / “Strings, that last phrase…” Davis considers for a moment. “I know I said it should be like a recitative in a Mozart opera, but I don’t think there’s space. So ignore me! Follow the click.”

A new cue is announced: “111.” The drummer puts down his book and flips through the score, then puts on his headphones. / A long confusion with stops/opens for the horns. / “OK, there’s some romance in the air”, Davis announces. / A good take. / “Mm”, says the maestro, “Yummy.” / Discussion of dynamics. / “We’re making a narrative point”, Davis interjects. “An eyebrow is being raised. Ha!” / Long interruption as Davis rummages for his phone. / “He’s hopeless!” calls a voice from next to me in the booth. It’s his wife.

The drummer is free again and busy drumming his leg, just above the knee. / “113.” / The timpanist hesitantly picks up his sticks and headphones, all the while inspecting the score. He sees he isn’t needed and replaces them, refolding his arms. / A great take! Violine is poisoned by her own hand!

The lead violin asks if a stronger phrasing will help. / Davis swoons with pleasure at the result: “Oh yes! Argh! Stabbed!” / The drummer is back into the depths of his book. / The bass-clarinettist stops the next take: “I’m sorry, there was an accident.” / “What happened?” Davis asks, concerned. / “I played the wrong note.” / “Oh, that’s all. I thought it was something serious and dental.”

Violine empties her vial once more. / “Perfect. Great.” / Violine is carried inside. Davis explains the strings are panting, and he himself performs a series of strange gasping noises. There is a touch of embarrassment among the members of his family in the booth.

Davis takes the first run-through too fast. / “I’m sorry”, he says. “I need to calm myself.” / There is a coffee break.

[Later]

Napoleon’s exclamation: “At last!” The orchestra produces a great smack of sound. / A tempo change is needed for the sake of an added shot of Napoleon’s hat at the end of the scene. / “I just need to learn the tempo of this”, Davis mutters. “I don’t want to do any more composing. I’m not writing an anthem for a hat.”

“At last!” Mobile phone interference. Once more… / “At last!” That was great. Once more for safety. / “At last!” I preferred the last one.

The scene complete, the orchestra returns to a much earlier scene. They will now accompany the hurdy-gurdy, recorded last week. / “Good moment for Trombone Three to be sinister”, Davis says encouragingly. / Davis explains that the accent for the title announcing “The Terror” is “a guillotine chop”. The players change the notation to read ff in their scores. “That first note needs to be startling.” Negotiations with strings. The suggestion they alter to mezzo forte is received with audible relief.

Robespierre and Saint-Just stand by while Danton is executed. / The drums are political, not military, Davis adds. / The high strings have trouble. / “Yeah, this is piano music” explains the captain. / Davis gets cellos and violas to give more extreme accelerando/diminuendo—they do so, mimicking the oceanic sway of the Double Tempest.

The orchestra is about to be introduced to the hurdy-gurdy. They must now play around the instrument, the sound of which will reach them through their headphones from last Friday. / The booth flicks a switch and the wheezing whine of the ancient instrument comes through. There are expressions of wonderment, giggles, and orchestral surprise. One violinist nods his head in appreciative rhythm. The bass-clarinettist looks at his colleagues and mimics the hand-cranking gesture of the absent hurdy-gurdy player. / Davis instructs the high strings: “This should be cold—icy—implacably cold.” He is describing Saint-Just.

The next cue: “France, in agony, was starving…” / “The music should be an atmosphere that’s specific to the film”, Davis demands. He alters the dynamics for “the sake of recording. Live, it’s another matter.” / The Captain speaks of 12th Vendémiaire: “I’d just like it in one performance without my having to cut it together later”.

Next scene. Brass and woodwind growl. “Wow!” exclaims Davis. “Wotan’s come in!” / Another scene. Violine’s “marriage” to the shadow of Napoleon. Gorgeous oboe and viola solos. / All tempo changes are removed. / “That’s slower than I ever intended.” / “This way it hits every cut.” / “If it hits every cut, I’ll buy it.”

Another cue. / “Woah!” Davis cries. “Eroica again. We’ll need a cup of coffee for this one.” / “We’ve got two big ones to do”, warns the helm. / “Two big ones?” / “Yup, and only one cup of coffee.”

[Later]

Afternoon session. / There is a debate over temperature. The helm wants the orchestra to be a degree colder to prevent tiredness: “I’d rather they whinge. Whingeing will keep ’em awake.”

The opening of the Victims’ Ball. / The first take sounds Viennese. / “No slows, please”, Davis instructs. The lead demonstrates the ideal phrasing and accents. / Second take. More French. “But what century?” Davis wonders. / Josephine’s fan. / Josephine is seductive, but the helm thinks the orchestra could be more “playful”.

Cue 96. This has been saved for the new guests to the booth. They whisper in respect whilst the guests on the screen let loose. / Beethoven’s Seventh. Whooping horns, racing strings, an orchestra champing at the bit. / “OK, now you’re doomed”, Davis says. “’Bones, you’re the doom!” / “It was here that I was summoned to the guillotine”, Josephine explains. / “It’s meant to be spooky and strange”, Davis interprets. “Apart from a lovely viola solo!” he adds, looking at the viola. / A great take. The orchestra applaud the viola. / Muted trombones. The ghosts of the Terror are moving in their graves, underfoot, in quicklime not yet set.

[Later]

Evening. The orchestra has gone down to a quintet. / Hypnotic chamber sonorities. A silent room. Uneasy quiet. Sinister work. / Saint-Just enters and the quintet falls into uncertain silence. They don’t know how to break it off. / Davis: “Here’s where the most awful man in the world comes in. It’s like Stalin walking in.”

There is an intimacy in the studio, the players gathered around the podium. / The lead violin asks us to make a note that one section of the last take was the best. The captain says we loved the whole take, but thanks him anyway and makes the note. / An error in the printed copy is spotted. / Each player takes great pride in this section. Each one asks to go further than the required repairs, hoping to better their execution.

The quintet becomes a quartet for a new scene. / The players can take the dynamics up a level for the sake of the recording—sound can “get the most out of the instrument”. / Davis’s page-turning of the paper score is amplified into a marvellously sensual solo sound in the helm. He stands a few metres away, but his handiwork flutters like a flock of birds’ wings in our ears. / Davis is enjoying the sound of the quartet so much he has rescored other scenes with Josephine for this small ensemble.

Josephine’s affair with Barras is ending. Davis tells the group: “It’s a romantic scene. They’re both adults. It’s coming to an end. People move on. It’s just one of those things.” / “Is it, Carl?”, chuckles his wife—unheard—in the booth.

The bass player is brought back (the violinist sprints out to open the doors) and we are a quintet again. / “Now this is very slow, and slightly boring”, the composer explains, “but that’s the point. Everyone is waiting—snoring.” / Josephine is waiting for her fiancé to turn up to their wedding. / Take one. / The captain encourages the players: “Just believe in the boredom, believe in the mundane, the banality.”

Now we are down to a single player: the solo viola. / A dialogue in an empty room. Violine’s marriage to the shadow of her absent beloved. / She is on her own. / Davis does not conduct her, but sits in silent contentment. / “It’s gorgeous. Really. And getting lovelier and lovelier.” / The pair discusses a couple of the awkward moments in the score, and they work out between them what is preferable. / Double-stops are dropped in. / Another take, now without click—the viola’s voice superbly alone, a true performance, free to float and find its own rhythm. / “This is so much nicer without the click”—the verdict of us all.

Friday, 2 October 2015

Davis’s voice wanders through a sea of noise. Fragments of his score peel away in disorder from individual players. There is a background hubbub of conversation, a landscape beneath a landscape. / Gossip stands next to a microphone, then passes—“Wine… crazy…” / A violinist squeezes along the rear of the studio wall, climbing up over the podium as she does so. She pauses whilst others make room on the other side. The conductor’s mic has the chance to eavesdrop on someone else. A brief snippet of conversation—the only words caught in the mic from her last phrase: “I’d better get down from the podium or I’ll start shaking.” (She is used to being at the back, on the extremity of the strings.)

The studio falls silent. / “Too still, too still!” Davis cries. “Move around—make some noise!” / The orchestra responds and flutters its woodwind, preens its brass, strokes its strings. / A technician wends his way through the forest to straighten the microphones for the woodwind.

Tuning. Click. / “No click for the violas”, Davis relays to the booth. / “No click for anyone!” someone adds. / Matt, one of the technicians, speaks to all: “I only have one job.” Laughter. / “The person responsible has now been fired”, the captain says in deadpan tones. The clarinets turn around in their seats to look into the booth.

We start with the release from prison, a dance to Beethoven. The dance lasts a fraction of a second too long. Frames are recalculated. / Another take. / Strings only, for balance. A half-empty cue springs from mic to mic, speaker to speaker. / Trumpets only. They play six notes, then stop. Bemused, they break off. The orchestra laughs, shout “Bravo!”—the two trumpeters stand and bow. / More takes. The horns are too raucous.

Haydn. Bonaparte refuses his command. / A new violinist stands to ask Davis a question. Consternation in the helm: “Who’s that? He’s gone up to the podium. The violins are revolting!” / Meanwhile, one of the clarinets is showing the other videos on his phone. / Davis spots an error in second oboe: “In bar 88, you should have an E natural.” / “I thought there was something strange there.” / “It’s a mistake that’s lasted 35 years.” / Captain: “Better late than never, Carl.” / More errors in the oboe part.

“OK, Josephine”, Davis speaks to the figure on-screen that the orchestra cannot see. / After the start of a cue, Davis stops the players to comment: “Late-morning droop. Cellos, it’s A-flat—it’s gotta spell love, it’s an exotic key. It’s Josephine—she’s coming, you can smell her perfume.” / Davis goes through with the strings. He can tell that not all give a pure A natural at a crucial moment. / Overlap is arranged to avoid the noise of a page turn. / Noise is checked on the playback, bar-by-bar, combing through the balance, mic by mic, to isolate the sound of page turns, to hunt down anomalies.

The “Three Graces” at the Ball. / The double-basses ask if they should double the cellos for the last bars. / “A low G? There’s a wonderful name for that on your instrument, isn’t there?” Davis asks. / There is: “The fire escape.”

The orchestra polish themselves to match the soft-focus. Strings are made to soften their steps. / “It’s moving but it’s smooth”, Davis summarizes. / Josephine smiles in recognition but catches her expression in her fan and gathers to herself the secret of her pleasure. / Coffee break.

Cello solo during the game of “Blind Man’s Bluff”. The run-through earns applause. / “I can’t give you that much legato, for time”, comments Davis. “Live, I could, but not for the recording.” / The second flautist has a magazine on her stand, hidden (from Davis’s point of view) behind the score.

A big march for Vendémiaire. / The timpanist is having fun. The music thrashes behind the glass of its cage. Napoleon strides in moody concentration. / In all the commotion, an oboist turns his page and a gust of air blows into the microphone. / Davis comments: “18 minutes ’til lunch.” / The voice of the helm, to everyone: “20 minutes by our watch.” / General laughter.

The game of chess. / The lead asks about phrasing. Davis wants staccato—“a little flirting”.

[Later]

Afternoon session. / The start of the Victims’ Ball. No violas. Darkness is banished. The viola player plays Sudoku; bassoons sit idle: the older of the two reads a magazine, the younger—perhaps more earnest—follows proceedings holding his instrument by his side. / Nigel’s horn solo as Napoleon refuses his command. The helm agrees: “So much better without the click.”

Davis explains the next cue, that of Josephine’s approach to Napoleon: “Very solemn, but very giggly at the same time.” / A 30 second break. In the quiet, the microphone relays Davis’s under-the-breath humming of the forthcoming cue. / The film demands a re-interpretation of the music.

The trumpets leave. Every time they have done so, someone has to get up and shut the door after them. “They never shut that fucking door properly”, a voice comments from the helm. So many times has he been asked to do it that the lead double-bass now goes without instruction to shut the door—getting up before the trumpets are even out of the room.

Violine is at her altar to Napoleon. / Solo violin, oboes, and flutes sound gorgeous. / The solo violin is now allowed to leave the click—but pizzicato strings must “stick with click”. “Live, I would give you some room”, Davis reassures them. / Another take, as Josephine tries on a series of hats. / “Stunning”, Davis adds at the end. “Carry on like this and we’ll definitely be going home early”. The orchestra applauds.

The orchestra now sits in silence whilst their sound reverberates in our booth. Davis takes off his headphones. We hear the mechanical heartbeat of his click through his microphone. / “Does he always have it that loud?” the captain asks. / “He seems alright”, someone responds, a smile evident in their voice. / “Blood’s trickling from his eyes, but apart from that…” / The booth dissolves into giggles.

[Later]

After a break, Napoleon is eager to rush through the marriage ceremony. “Skip all that!” he cries. / The registrar fumbles ahead in the sheets of official procedure; Davis increases the tempo. / A quick break. / A string player manages to segue from Beethoven’s Creatures of Prometheus to a sea shanty.

The end of the day. The orchestra has left. A series of short, stocky men clear the floor and the piano is manoeuvred into the centre of the space. The shortest of the group sets about tuning the strings. Notes, then chords, emerge from the piano. Everyone looks on at the laborious work and checks their watches.

Davis is now at the piano, grinning. “This is the Hitchcock moment!” He is about to appear in his own score. / The first take. / He practices the cue while we listen to the last take being played back in the booth. Davis is unwittingly performing a duet with himself.

Paul Cuff