This piece is inspired by a recent trip to Amsterdam to visit the archive of the Eye Filmmuseum. Here, their collection specialist Leenke Ripmeester was an exceedingly helpful host. She not only showed me a unique print of Gance’s first sound film but also introduced me to some fantastic online resources where I could research historical film distribution in the Netherlands. The most remarkable for me was “Cinema Context”, an amazing database containing information from the Dutch film censors and contemporary press reports. (Leenke told me that she herself, in her student days, was part of the team who collated the data from contemporary documents.) It strikes me as a fabulous project, one that I wish every country would pursue. This, together with the newspaper archive, proved tremendously useful in revealing how, when, and in what form Gance’s films were shown in the Netherlands during the 1920s-30s. What follows is a brief account of my visit to the archive that afternoon, and what I have discovered about Gance’s silent and early sound films in the meantime…

Films produced by Le Film d’art (1915-1917)

The earliest reference to Gance’s name in the Netherlands press is in 1915, when he had started working for Louis Nalpas’ production company Le Film d’art. His first assignment—as scenarist—was Henri Pouctal’s L’infirmière (1915). The film was released in the Netherlands and the adverts even featured Gance’s name alongside that of Pouctal (see below, from the Arnhemsche courant (17 June 1915)). Thereafter, Gance assumed the direction of his own scripts, and Le Film d’art productions seem to have been distributed in the Netherlands throughout the war years.

L’Énigme de dix heures (1915). First released in France in August 1915 in a version of 1200m. First shown in the Netherlands in December 1915 under the title “Het Raadsel van klokslag tien”.

La Fleur des ruines (1915). First released in France in late 1915 in a version of three parts (sometimes listed as four parts). First shown in the Netherlands in November 1915 under the title “De Lelie der puinen” or “Een lelie tusschen de puinhoopen”. There is no known length listed for the French version, but the Dutch censors record the length as 900m. (This is the first time Gance is mentioned by name in the reports.)

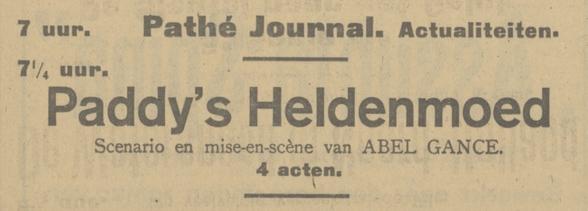

L’Héroïsme de Paddy (1915). First released in France in October 1915 in a version of three parts. First shown in the Netherlands in January 1916 under the title “Paddy’s heldenmoed”. There is no known length listed for the French version, but the Dutch censors record the length as 1200m. An advert in the Arnhemsche courant (26 January 1916) describes the film as being in “four acts”.

Le Fou de la Falaise (1916). First released in France in January 1916 in a version of 1180m in three parts. First shown in the Netherlands in May 1916 under the title “De Gek van de klippen” or “De Dwaas van de rotsen”. Dutch censor also gives length as 1180m.

La Droit à la vie (1917). First released in France in January 1917 in a version of 1355m (some filmographies say 1600m). First shown in the Netherlands in March 1917 under the title “Een Kind uit het volk” or “Het Recht om te leven”. Described by the censor as a “social drama in four acts” with the original act titles: “1. De brand, 2. Oproer, 3. Haar offer, 4. Uitgestoten”.

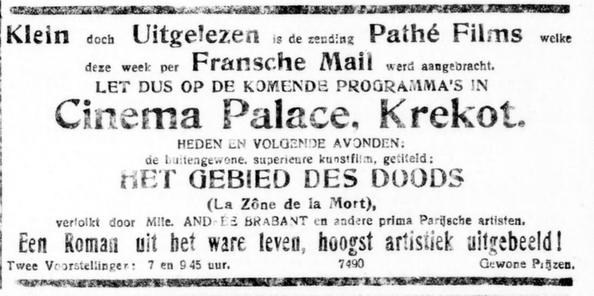

La Zone de la mort (1917). First released in France in October 1917 in a version of 1535m. First shown in the Netherlands in July-August 1918 under the title “Het Vuur” or “Het Gebied des doods”.

Barberousse (1917). First released in France in April 1917 in a version of 1600m. First shown in the Netherlands in December 1921 under the title “De Bende van Barbarossa”. Dutch censor gives length as 1700m (100m longer than Gance filmographies state). After a much-delayed release in Leiden in December 1921, the film was then rereleased in Rotterdam in April-May 1922.

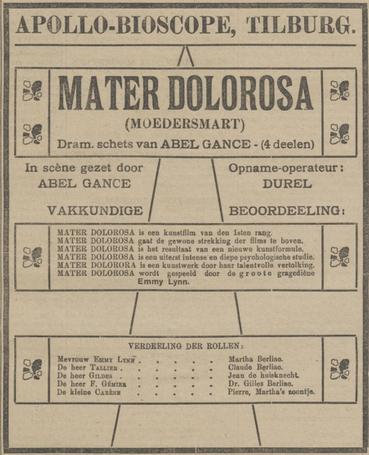

Mater Dolorosa (1917). First released in France in March 1917 in a version of 1510m. First shown in the Netherlands in April 1917 under the titles “Vrouwennoodlot”, “Een Moederhart verloochent zich niet”, or “Moedersmart”. Dutch censor gives length of 1344m and an age certificate of 18+. (This is the first Gance film I have found in the Dutch records to be given an age rating.) The film was rereleased in the Netherlands in June 1920 and again in February 1924.

La Dixième symphonie (1918). First released in France in November 1918 in a version of 1510m. First shown in the Netherlands in October 1919 under the title “De Tiende symphonie”. The release date suggests the film was shown in the wake of J’accuse, presumably to capitalize on the latter’s commercial success (see below).

Films produced by Pathé (1919-23)

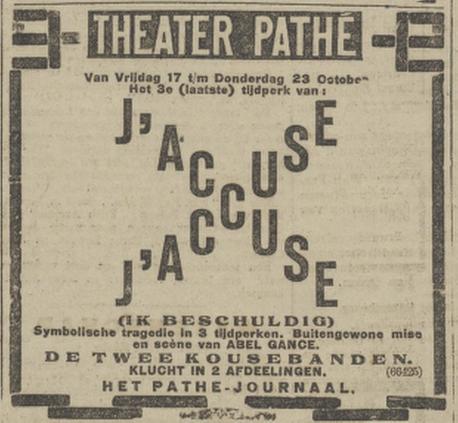

J’accuse! (1919). First shown in France in March-April 1919 in a four-part version of 5250m, released generally in a three-part version of 4350m, rereleased in a version of 3200m in 1922. First shown in the Netherlands in September 1919 under the title “Ik beschuldig”. Censorship records record the length as 4500m (150m longer than Gance filmographies state), divided into three parts. The film evidently had a wide release across the Netherlands, as there are records of screenings in various locations from late 1919 through to September 1920.

La Roue (1922). First shown in France in December 1922 in a six-part version of 11,000m, released generally in a four-part version of 10,495m, then rereleased in 1924 in a two-part version of 4500m. First shown in the Netherlands in a two-part version of 4632m in March 1924 (The Hague). Gance filmographies state the length of the two-part version (which Pathé intended to be the standard export version of La Roue) as 4200m or 4500m, but the Dutch records give a precise length. The records note the title of part two as “De Witte symphonie”, which matches the evidence that the 1924 version was divided into “La Symphonie noire” (part one) and “La Symphonie blanche” (part two). The Dutch censor gives an age certificate of 18+ for La Roue for “ongezonde, krankzinnige vertoning” (i.e. “unhealthy” displays of “mad” behaviour). The film was successful enough to be rereleased in the Netherlands in March 1925 (Amsterdam and Rotterdam) and again in February 1927 (Leiden).

Au secours! (1924). First released in France in October 1924 in a version of 900m. A 752m version of the film was passed for censorship in the Netherlands in October 1928 under the title “Max Linder en het spookslot” but there is no indication that the film was exhibited. The Dutch censor gives this film an age certificate of 18+ for “griezeligheden” (“creepiness”!).

Napoléon, vu par Abel Gance (1927)

Well, such are the complexities of this film that it needs its own section. Napoléon was first shown in France in April 1927 in a version of 5200m with triptych sequences (the “Opéra” version), then released in May 1927 in a version of 12,961m without triptychs (the “Apollo” version); subsequently prepared for international distribution in a version of 9600m with triptychs (the “definitive” version). First shown in the Netherlands in August 1927, then rereleased in March 1929 and September 1931.

Given the innumerable different versions of the film released in 1927-28, many without supervision by Gance, it is difficult to tell in what form Napoléon was exhibited in the Netherlands. It is possible that the version shown in August 1927 was the same version seen in Berlin in October 1927 and subsequently released in central Europe through UFA. This version was around three hours, which would accord with the Dutch records providing a length of 3946m (170 minutes at 20fps) for Napoléon. However, the film’s Dutch premiere in The Hague predates the first censorship records from March 1929. Though the length of the film is given as 3946m, there are also separate records for two “episodes” of this version: part one is 973m, part two is 1033m (i.e. a total length of only 2006m). The censor records six cuts were made to the version shown in 1929, due to “schijn van ongeklede dames” (i.e. scantily-clad women). The 1931 file states the film has two “episodes” that pass without cuts. For its screenings in 1929, the exhibition records reveal that Napoléon was shown in a programme that also included several films by Walter Ruttmann: the avant-garde shorts Opus II (1922), Opus III (1924), and Opus IV (1925), together with his feature documentary Berlin: die Sinfonie der Grossstadt (1927). Given the potential length of this programme, it would indicate that only a severely reduced version of Napoléon was shown in 1929—perhaps even a version amounting to extracts of the major sequences.

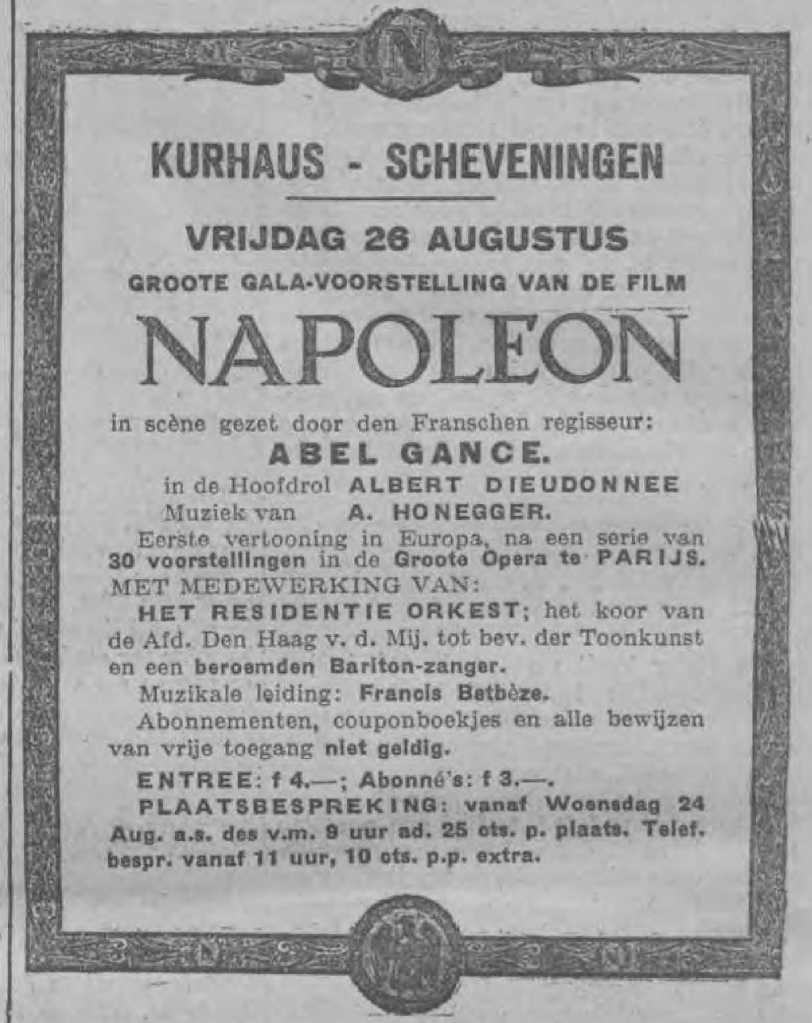

But it is the film’s first exhibition in the Netherlands that intrigues me most. Contemporary reviews indicate that the version of Napoléon shown there in 1927 measured 4000m (De locomotief, 1 October 1927; De Telegraf, 27 August 1927), which accords with the 3946m length given in the censorship records. This version had its gala premiere in the Kurhaus, The Hague, on 26 August 1927. It was clearly a major screening in a grand location (see an image of the venue below).

Musical accompaniment was provided by the 82-man resident orchestra and the 40-strong chorus of the Haagsche Toonkunst, together with the baritone Tilkin Servaes (Het Vaderkabd, 13 August 1927). The conductor was due to be Francis Betbèze, but he was ill the day of the premiere so was replaced by a Mr. Schuyer. The score itself was that written and arranged by Arthur Honegger for the film’s premiere at the Paris Opéra in April 1927. Before reading the Dutch press reports, I had no idea that Honegger’s score was ever performed outside of France in 1927. It must have been specially arranged by Betbèze or Schuyer, because Honegger’s score was designed to accompany a longer version of the film (the Opéra print ran to 5200m, 1200m longer than the Netherlands version). There was also the inherent issue of the score being a rushed and unsatisfactory project. Reviews of the premiere performance in Paris describe Honegger’s music as being badly performed (as well as poorly arranged) and often clashing with the film. This isn’t surprising, given that Honegger walked out on Gance before he had finished work on the score—there were doubtless last-minute changes in editing that meant the music had little chance of synchronizing throughout. So how did the music fare in The Hague performance?

The review of the premiere in De Telegraf (27 August 1927) indicates that the music was as much a failure here as it had been in Paris. Due to bad timing (whether due to projection speed or musical error), the solo baritone had to sing the Marseillaise “at a gallop”. The choir was likewise “forced to sing at a tempo apparently much faster than it had rehearsed”. But this was only one instance of a general problem:

Honegger’s accompanying music has not taken any further steps in solving the problem of film music. One does not get the impression that this music was composed especially for the film. On the contrary. Scenes in which the obsessive violence of revolution can be seen on screen are sometimes accompanied by an idyllic duet of two flutes. Modern and modernist sounds are unleashed on the film when a piano is seen on screen: the piano is represented by a celesta while the orchestra plays Mozart’s B-flat aria from The Marriage of Figaro. No trace of style. Indeed, in many places the music destroyed the mood evoked by the film images. The last act of the film is apparently not accompanied by Honegger’s arrangement. The potpourri then performed has a cheap allure. Thus, the performance ended in a vocal and instrumental debacle. Music synchronized with images: this ideal was a long way off from the premiere of Napoleon!

These are much the same issue cited in the performance of Honegger’s music in Paris. Doubtless, the textual changes to the 4000m version shown in The Hague exacerbated the existing issues with synchronization in the score. But the mere fact that Honegger’s original score accompanied the film is itself an indicator of the effort put into the exhibition of Napoléon in the Netherlands. The press reports feature photos of Gance, and the reviews repeatedly use the word “masterpiece” in their advertisements. However flawed its musical presentation, the film itself made a critical impact.

One last note to add to this section is the fact that Jean Arroy’s documentary Autour de Napoléon (1928) was also shown in the Netherlands. It was first released in France in February 1928 in a version of 1200m. It was released in the Netherlands in May 1928 (at the Centraal Theater, Amsterdam and the Corso cinema, Rotterdam). That it was exhibited at all in the Netherlands indicates that Napoléon generated public interest. After all, various versions of Napoléon continued to circulate there throughout 1927-31.

La Fin du Monde / Das Ende der Welt (1931)

The history of La Fin du monde is exceedingly complex. (For a full account of the production and its context, I refer readers to my book on the subject.) In brief, before surrendering control of the editing to his producer, Gance assembled a version of 5250m (over three hours). The version that was ultimately released was only 2800m (c.100 minutes). It was first shown in Brussels in December 1930, then began its general release in France in January 1931. The German-language version, Das Ende der Welt, was first shown in Zurich in January 1931, then began its general release in Germany in April.

When La Fin du monde is first discussed in the Dutch press, it is under the title “Het Einde der wereld”, the literal Dutch translation of “La Fin du monde”. The Paris correspondents of various Dutch newspapers reported on La Fin du monde and highlighted all the faults that other critics noted (exaggerated performances, poor sound, inept editing). Given that both the film’s production company (L’Écran d’art) and its main distributor (Les Établissements Jacques Haïk) went bankrupt by the end of 1931, it’s not surprising that La Fin du monde was not taken up by distributors in the Netherlands at this stage. A comment in Het Vaderland at the end of the year summed it up well: La Fin du monde “has not yet been shown in our country, but in Berlin it has already sunk like a brick” (19 September 1931).

Although the film was not yet released in the Netherlands, the French-language version had been submitted to the censor in March 1931. I was very intrigued to discover that these records give a precise length for La Fin du monde of 2906m, longer than the 2800m usually cited in filmographies. The files show that the film was given an 18+ rating, describing the film as “sensational, exciting, confused” and included a “banal image of suffering Christ”. Six cuts were made, all of them to the “orgy” sequence near the climax of the film. (One gets the impression of a protestant sensibility in the Dutch censors’ office.) But despite being passed for release, La Fin du monde was not shown in the Netherlands in 1931.

There is a second file from May 1935. The film is now referred to as “Het einde der wereld”, the literal Dutch translation of the French original. But the film is still not released. In December 1935, the film once again comes before the censor—this time under the new title “De Verwoesting van de wereld”, i.e. “The Destruction of the World”. However, the print being submitted is not the French-language version of the film, but the German-language version: Das Ende der Welt. The censor again gives the film an 18+ rating for the film’s “sensational tenor and frivolity”. Two cuts are recorded, totalling 76m of footage. (No content description is given, but one presumes it was the same orgy sequence that again brought out the scissors.)

In June 1936, over five years since it was first shown in Switzerland and Germany, Das Ende der Welt was finally released in the Netherlands under the title “De Verwoesting van de wereld”. It was shown at the Roxy cinema in Leiden, then in various other cities across 1936-37. Why did it take so long for the film to reach the Netherlands? One reason is that the film was such a flop in 1931 that it was perhaps wise to wait until the memory of its failure had faded. For by 1936-37, newspapers were announcing “De Verwoesting van de wereld” as if it were a new production. (Perhaps the title was changed precisely to dissociate the film with its original release.)

The Arnhemsche courant, for example, carried a hyperbolic advert announcing the “gigantic film masterpiece by the genius director Abel Gance” (26 August 1937). The tone of the Dutch press pieces strongly echoes the advertisements in the German press in 1930-31, which also emphasized the scale of the spectacle and the numbers of extras. It is worth noting that it was Viatcheslav Tourjansky who had supervised the editing of the German-language version of Gance’s film. Very little is known about how either the French or German prints were assembled for their release, so the existence of “De Verwoesting van de wereld” is a significant piece of evidence. The adverts for its release in 1936 say the film lasts two hours, though the censor record of 2906m suggests an actual time of 105 minutes. However, with a fifteen-minute interval, you can easily imagine the film becoming a two-hour showing.

There are surprisingly few reviews that I can find from 1936-37, and none of anything like the length of the reviews sent from Paris correspondents to the Dutch press in 1931. The Nieuw weekblad voor de cinematografie calls it an “exciting film” and reassures its readers that the epic story is in the “safe hands” of Abel Gance (17 April 1936). (I think this is the only time I’ve ever seen Gance referred to as a pair of safe hands!) The Dagblad van Noord-Brabant mentions the film’s scale and number of extras but offers scant comment on its quality (20 February 1937).

But thanks to the Eye Filmmuseum, I can at least offer some comment on “De Verwoesting van de wereld”: for a print of 830m (thirty minutes) is preserved in their collection in Amsterdam. I had long thought that no copy of the German version of Gance’s film survived. (I had even said so in print!) So I was incredibly excited to see even this fragment of Das Ende der Welt. The print had Dutch introductory credits and Dutch subtitles, but the soundtrack was most definitely in German. For this, I knew from my earlier research that the main performers (Abel Gance, Victor Francen, Samson Fainsilber etc) had been dubbed by German actors. Only one actor was recast for the German version: Wanda Gréville (credited as Vanda Vengen) replaced Colette Darfeuil from the French version. (Gréville was English but spoke German fluently. She was also intended to shoot scenes for an English-language version of the film, but this version was never assembled in 1931. The version of the film released in the US in 1934 was the French version with English title cards and subtitles.)

Sadly, the first third of the film is entirely missing from the Dutch copy, so there is no sight of Gance as Jean Novalic at all—I had so hoped to hear what he sounded like in the German dub. But Victor Francen as Martial Novalic is there, dubbed in authoritative German. I also spotted at least two scenes featuring German dialogue recorded live on set (i.e. not dubbed), but only with minor characters. Most of the Dutch print consists of the climactic scenes of the comet approaching: we see crowds fleeing in panic, nature running amok, extreme weather etc. Amongst this material are several shots that do not survive in the French version, but nothing significant. Sadly, there is no sign of Wanda Gréville. I had also wondered if there were any extra scenes missing from the surviving French-language copies of the film. The recent Gaumont restoration of La Fin du monde runs to 94 minutes, several minutes short of the prints shown in 1931. But aside from a few very brief shots, there are no major discoveries in the Dutch print. (The only shot that was suggestive of a missing sequence was one shot of Martial Novalic behind-the-scenes at the “Universal Convention” in the last minutes. Assuming this is him after he makes his grand speech, it would belong to the scenes in which he is—according to the script—finally reunited with Geneviève.)

Though it is only a fragment of “De Verwoesting van de wereld” as it was shown in 1936-37, the surviving Dutch print survives in very good visual quality. The viewing copy I saw was an acetate dupe of the 35mm nitrate print held in the archive, so the original should look even better. The 35mm print was part of a private collection of reels purchased by the Eye Filmmuseum in the 1960s. No further information is known about the history of this particular print, or how it ended up being reduced from c.105 minutes to just thirty.

Summary

This was only my second trip to Amsterdam. The first was in 2014 for a screening of Napoléon at the Ziggodome. Here, the film was projected on 35mm and accompanied by Carl Davis conducting the Het Gelders Orkest. This was the most extraordinary performance of the film I have ever seen. For the final triptych, the three screens measured a total of forty metres wide and ten metres tall.

My trip to the Eye Filmmuseum to see the fragment of Das Ende der Welt on a small screen was less spectacular, but nevertheless rewarding. I knew nothing about the print until revisiting the FIAF database in 2021. The mere existence of the print is a miracle, especially as it led me to explore the wonderful Dutch archive sites and discover all kinds of new information on the distribution of Gance’s films. It just proves to show how much more can be gleaned if only you know where to look. And I do hope more of any version of La Fin du monde turns up. (Of course, the mythical three hour cut that Gance assembled would be a dream, but the chances of it existing at all are infinitesimally small.) I have just seen that Kino is to release the recent Gaumont restoration of La Fin du Monde on Blu-ray in North America. Sadly, there are no new extras. Will someone be keen enough to offer a UK release? If so, I can certainly recommend at least one extra: the Dutch print of Das Ende der Welt. (And I know at least one person who’d be keen to do another commentary track. Ahem…)

My thanks once again to Leenke Ripmeester for her time and help within and beyond the archive.

Paul Cuff