There are some silent films better known for their music than for their images. This is one of them. Produced by Ufa in August-December 1924 and premiered in Berlin in February 1925, Zur Chronik von Grieshuus was originally accompanied by a lavish orchestral score composed by Gottfried Huppertz. Though Huppertz died aged only 49 in 1937, he produced two of the most famous original scores of the silent era. These were both for Fritz Lang productions, the epics Die Nibelungen (1924) and Metropolis (1927). For these alone, Huppertz is rightfully well known – but they have rather eclipsed his music for Zur Chronik von Grieshuus. This film was a major Ufa production and boasted an impressive roster of talents: a major screenwriter (Thea von Harbou), big stars (Paul Hartmann, Lil Dagover), and important set designers (Robert Herlth, Walter Röhrig, Hans Poelzig). Perhaps the least known of all the figures who produced the film is its director. Arthur von Gerlach was primarily a theatre director and made just one other film in his entire career, Vanina (1922). A century after its release, we are now more likely to watch Zur Chronik von Grieshuus for its writer, stars, designers, or (perhaps especially) for its music. But what of the experience as a whole? What is the balance of music and images in Zur Chronik von Grieshuus? Does Huppertz outshine Gerlach?

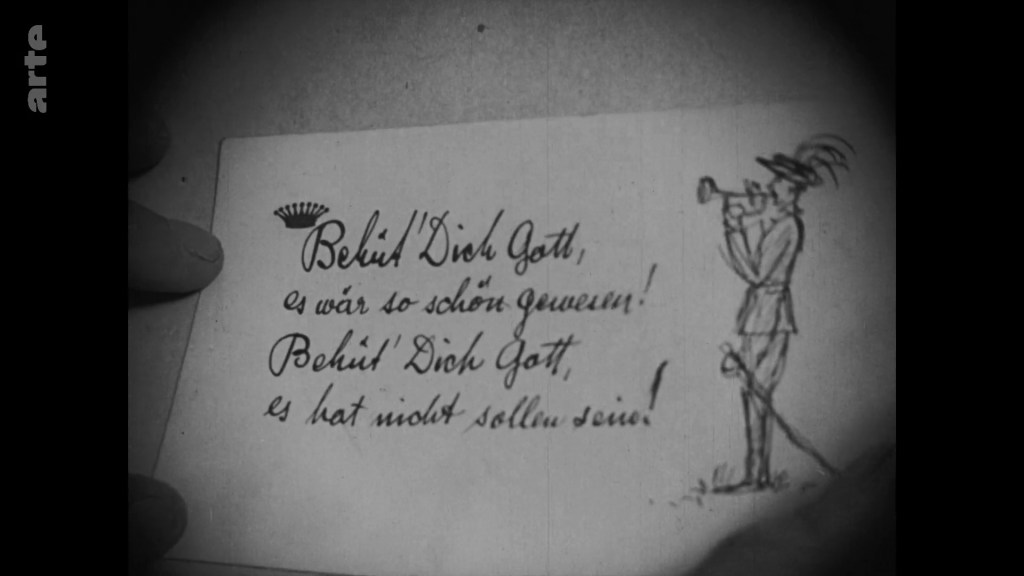

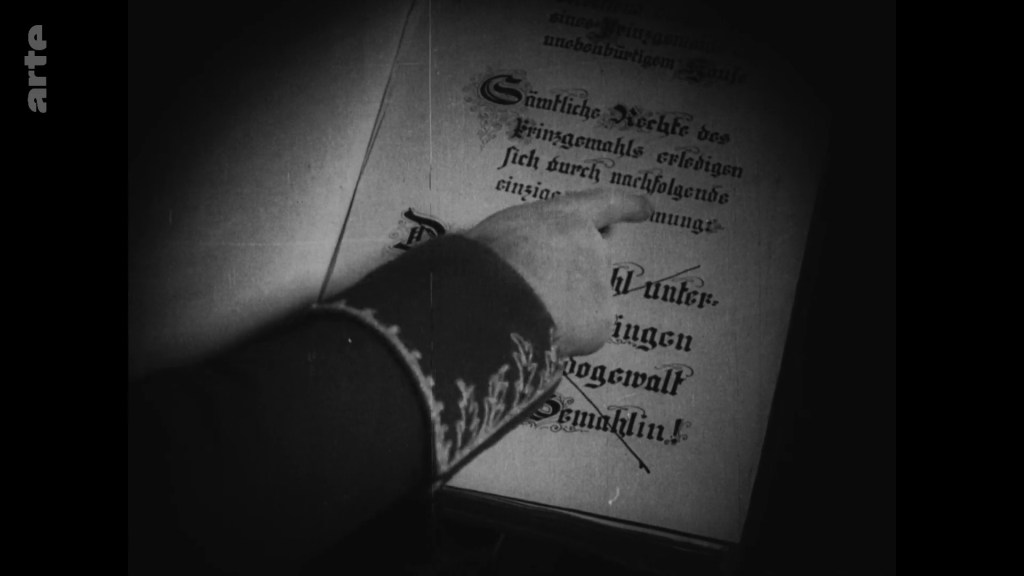

First, the plot. The film is a romantic historical drama, adapted for the screen by Thea von Harbou from a novel by Theodor Storm (1884). In seventeenth-century Germany, the lord of the castle and estate of Greihuus (played by Arthur Kraußneck) has two sons: his favourite and heir, Hinrich (Paul Hartmann) and the embittered Detlev (Rudolf Forster). However, when Hinrich falls in love with Bärbe (Lil Dagover), the daughter of a commoner, he is disinherited – and Hinrich’s father destroys his old will. Meanwhile, Detlev is wooing the wealthy Gesine (Gertrud Welcker), widow of Count Orlamünde. Detlev argues with his father over the making of a new will that would guarantee his rights to the estate and thus aid his claim for Gesine. There is a violent confrontation between father and son, and the father dies. Without a will, a bitter struggle for the inheritance ensues between the two brothers. Detlev marries Gesine and Hinrich marries Bärbe, who is soon pregnant. However, after a heated argument, Hinrich kills Detlev and flees in panic – and Bärbe dies giving birth to a son, Rolf. After several years, Gesine returns to try and seize Grieshuus in the name of her murdered husband. She kidnaps Rolf, but the ghost of Bärbe guides Hinrich to the child’s rescue. Mortally wounded by Gesine’s henchman, Hinrich returns his son to Greishuus before dying. ENDE.

If the novel and its author were associated with realism, and there is a kind of balance between expressionist and realist tendencies in Gerlach’s film. There are marvellously sturdy sets designed by the experienced team of Herlth, Röhrig, and Poelzig. The castle and its walls, the farms beyond, and the shadowy spaces within – all these are rendered with tremendous care. The texture of the on-screen world is palpable. The thickness of the walls, as evidenced in the deep recesses of doors and windows, creates a real sense both of a past stretching beyond the time of the drama – and of a world that is rooted in solidity and tradition. This is a drama of lineages being broken and rebuilt, and it takes place within a world that seems rooted in the ground. The castle tower is like an ancient tree trunk, gnarled and pockmarked with age – but holding out (just) against time. The massive gates and doors almost grow out of the earth, their gothic archways and entrances evoking organic (not to say, bodily) shapes. All these spaces are wonderfully lit, emphasizing with subtle light and shade the texture of the rooms, the walls, the floors, the drapes.

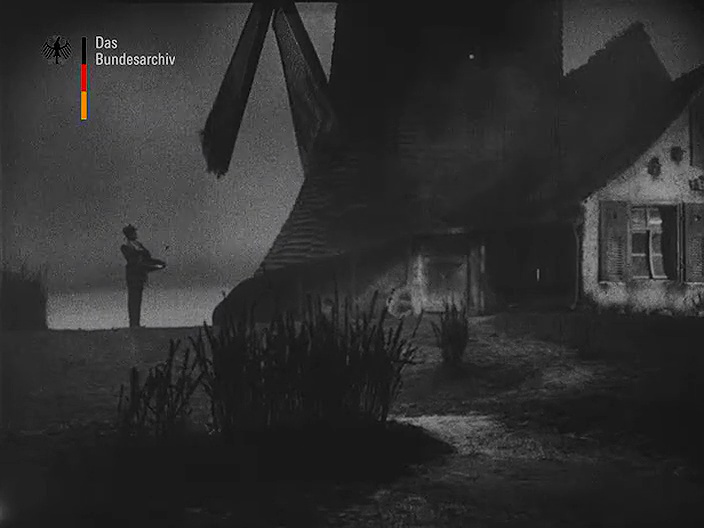

Our expectations of a prestige Ufa production of the mid-1920s may well make us think of studio-bound spaces and carefully designed recreations of the outside world. But Zur Chronik von Grieshuus is a very outdoorsy film. The exterior spaces are superb. I’d love to visit the open landscape of Lüneburger heath, in northern Germany, where many of these scenes were filmed. The moors are both forbiddingly empty but also filled with hidden details: little pockets of marsh and outcrops of rock, peppered with stunted trees and bushes battling against the wind. Gerlach films plenty of scenes in the landscape where characters are silhouetted against the eternally cloudy sky. Zur Chronik von Grieshuus has a marvellous atmosphere that is sustained throughout.

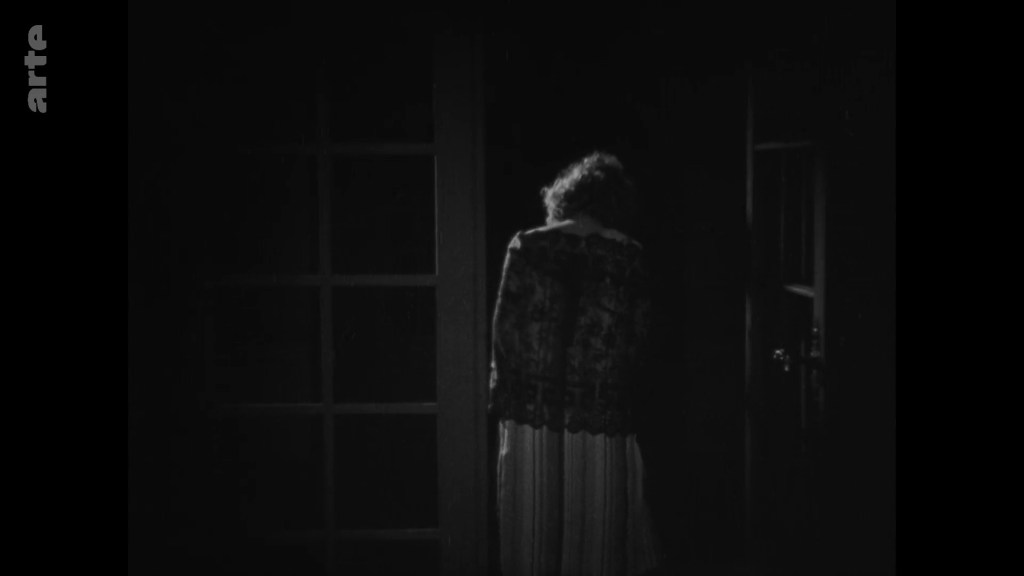

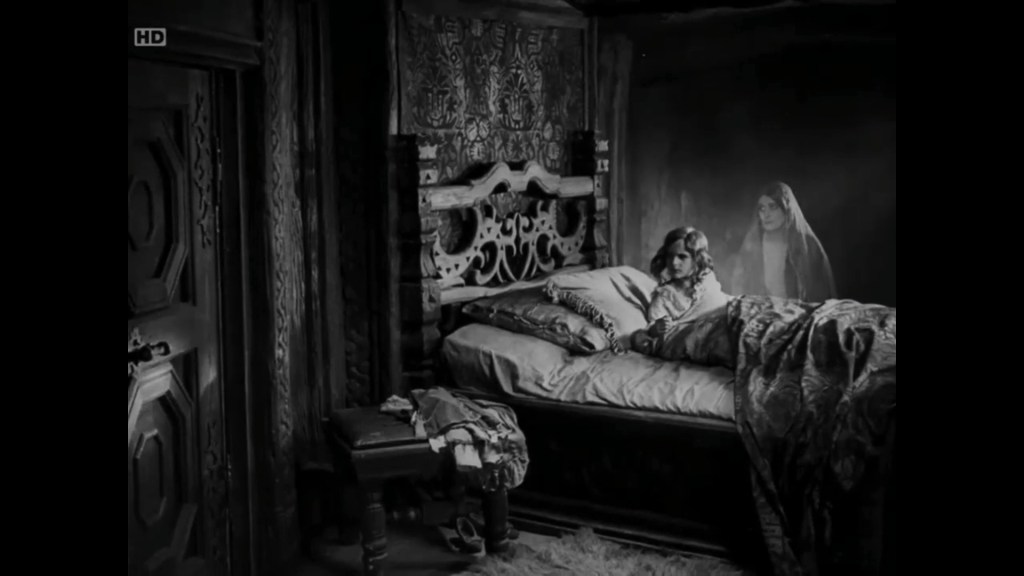

The landscape of the moor is also the site of the film’s most impressive sequence: the final ride-to-the-rescue in which Hinrich finds and saves his son. Gesine has previously been frightened by the ghost of Bärbe, whose spectral form now appears at intervals to guide Hinrich across the gloomy nighttime expanse of moor. When she appears for the first time outside, we see her form, uncannily bright, on the dark, distant horizon. It’s an image of stunning power, instantly gripping and memorable. The death-pale figure, arms aloft; the silhouetted trees; the blank sky; the empty landscape: these elements are like an Arnold Böcklin painting come to life. But the difference between this moving image and Böcklin’s paintings lies precisely in the sense of movement Gerlach’s film provides. The wind whips the white shroud of the ghost: she is all at once a human figure, a wraith, and a pale flame flickering on the dark horizon. Marvellously, when Henrik enters the frame in the foreground, the flank of his horse flashes white, caught in the beam of an off-camera lamp somewhere to the left. It’s a superb touch, visually linking the (living) Hinrich with the ghost of his wife who guides him to his destination. And throughout the shot, the dark trees are caught between stillness and movement: rooted to the ground, their canted bodies have clearly grown and bent permanently in the wind, which still bustles their branches. It really is a stunning shot. It’s the best shot in the film, and I wished some more images were this striking.

The image – and its unique visual power – is at the heart of my reservation about the film, a reservation that makes me think it a very good but not a truly great film. Everything in Zur Chronik von Grieshuus is visually impeccable and, in its own way, perfect – but neatness, everything-being-as-it-should-be, is sometimes not enough. The film builds up a great momentum in its final two acts, but of all the impeccable images on screen, the shot of the ghost on the moor is the only one that took my breath away. This film’s closest kin, Lang’s Die Nibelungen or F.W. Murnau’s Faust (1926), are filled with images that immediately sear themselves into your brain. Of course, those films are more overtly expressionist and fantastical than Zur Chronik von Grieshuus. But the visual language of Die Nibelungen and Faust is, in just about every aspect, more sophisticated, more complex, and more emotionally engaging, than that of Zur Chronik von Grieshuus.

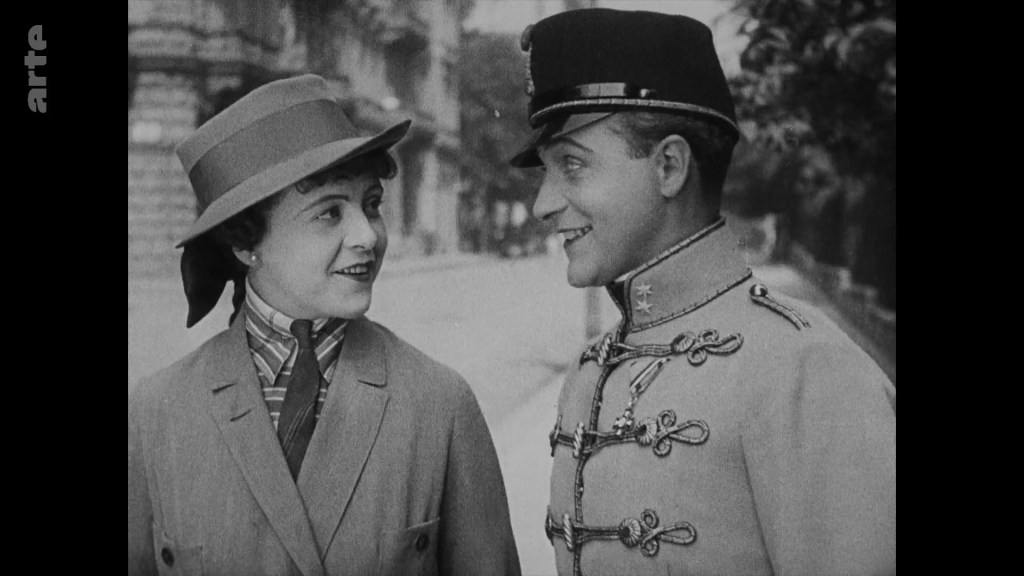

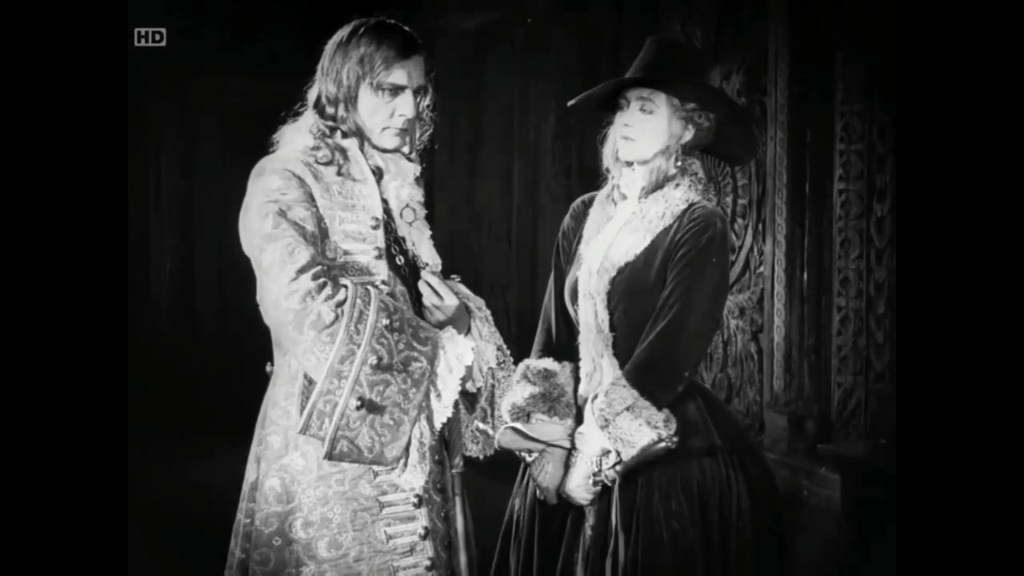

I feel much the same about Gerlach’s cast. Paul Hartmann is engaging enough, handsome enough, and heroic enough as Hinrich – but the character’s struggles are impeccably rendered without ever being moving. Ditto Lil Dagover as Bärbe. The image of her as the ghost is far more emotionally effective than any of her gestures when she was living. As the slightly foppish Detlev (the man his father calls a “pen-pusher”), Rudolf Forster is pleasingly scowling – but never a caricature. This both saves his performance from being unrealistic or comic, but it also limits him to being effective rather than affective. His wife Gesine, however, is the closest the film gets to a stand-out performance. Gertrud Welcker looks utterly fabulous at every turn – and she gets the best chances to pose in her costumes: looking pissed-off in her dark, fur-trimmed dress and big hat; looking pissed-off in a huge ruff; looking pissed-off in a huge cloak. But the film is reticent to exploit her or her character to the full. (It is reticent with her, or with anyone else, to offer a proper close-up to maximalize drama and emotion.) Only in the final act does Gesine take action, and even here she is soon scared off and gets her henchman to do the kidnapping.

I said at the outset that one of my prime reasons for watching Zur Chronik von Grieshuus was its score by Gottfried Huppertz. This had been written during the film’s production in 1924, so it enabled a precise collaboration between composer and director – and thus between music and image. The score was performed at the premiere at the Ufa-Palast-am-Zoo and again at select presentations elsewhere. The music was then published in versions for full orchestra, for cinema/salon orchestra (c.13 players), and for piano. While cinemas therefore had the option to model Huppertz’s music for their respective forces, the score was not performed again until its reconstruction and recording by ZDF/ARTE in 2014. The film itself had already been restored by the Friedrich-Wilhelm-Murnau-Stiftung in 2004-05, so it was a case of editing the surviving musical material to fit the completed version of the film. Indeed, as the accompanying notes to the film admit, it was the importance of Huppertz as a film composer that motivated the full audio-visual restoration of Zur Chronik von Grieshuus in 2014 – and the release of the film on DVD (in 2015), together with a recording of the complete score on CD (in 2016).

So, does this music outshine the film? Well, no, I don’t think it does. Huppertz’s music for Zur Chronik von Grieshuus is much in the same vein as his more famous scores for Die Nibelungen and Metropolis, carefully matching the action with a rich soundworld – together with swift and regular changes of tone and tempo to fit each scene or character. Hinrich’s music is bold and sometimes boisterous, as when he rescues Bärbe from marauding soldiers (who likewise get their own rather fun, lumbering brassy theme). Bärbe’s theme is slow, sweet, and bright, a kind of balm in the midst of the drama. Detlev gets a rather sinister, sloping theme – like someone moodily pacing back and forth. Though we hear them throughout the film, these motifs never sound quite the same twice – everything is subtly modulated, shifted, combined, contrasted. The occasional use of the organ, bells, anvil, and wind-machine also blends something of the world on screen into the music. It’s all very pleasing, a warm, rich texture of sound.

However, just as the film is often too well behaved to be striking, so too Huppertz’s score. In this sense, it is perfectly suited to the images: well-planned and well-executed without every really grabbing your attention. Whereas I can immediately summon the main musical motifs of Huppertz’s score for Metropolis, and certain orchestral effects in his score for Die Nibelungen, I find it difficult to summon too many themes from his Zur Chronik von Grieshuus. Of course, I have not watched the film with the music as many times as I have the other films; but I have listened to the score on its own, and I can only restate that it feels less distinctive than its two cinematic/musical peers. I suppose the naturalistic edge of Gerlach’s film keeps the score from too many flights of fancy. As I have said throughout this piece, both images and music are (for the most part) too well arranged and co-ordinated to leap out from their own world and impose themselves in our imaginations.

More generally, my sense is that Huppertz’s score almost seems to be waiting for the drama to pick up speed before it becomes more interesting. When it does, as at the start of Act IV (about an hour in), there is a noticeable upping of urgency. This fourth act begins with Detlev and Gesine plotting to contest Hinrich’s legal right to the inheritance and ends with the deaths of Detlev and Bärbe. In the space of a few bars of music, Huppertz not merely sets the scene (i.e. conjures music to match the opening images) but suggests the entire mood of the act. There is no storm visible on screen, but the orchestra booms and the wind-machine roars. Something is looming on the horizon, something that we cannot see but we certainly feel thanks to the score. It’s perhaps the first instance in the film where Huppertz’s score creates a kind of counterpoint to the image. Indeed, I am tempted to say that it is the first scene when the music attains a kind of independence from the images on screen. I might even say that the music here assumes a kind of agency: it is thinking ahead of the images before it (and us), pointing to the drama to come. This is music that predicts the drama.

If my overall impression of the film is one of balance and accommodation, this is not true of its cultural afterlife. As I said at the outset of this piece, Huppertz remains far better known than Gerlach. You can easily buy either the complete or the abridged modern recordings of his scores for Die Nibelungen and Metropolis. (Indeed, you can even listen to the small selection of motifs from Metropolis that were recorded with orchestra by Huppertz in 1927, preceded by a short address spoken by Lang, and released on disc(s) by Vox.) You can also buy the complete modern recording of his music for Zur Chronik von Grieshuus, which was released on a 2xCD set in 2016. However, the DVD of the film itself (released in Germany in October 2015) is now utterly, utterly unavailable anywhere in the world. (Even an ISBN search yields a slim parade of extinct product listings.) I am clearly several years too late to find a copy. Gerlach is gone, but Huppertz remains.

This is a salutary lesson. The DVD of Zur Chronik von Grieshuus is (or was) part of a longstanding series of restorations by the Friedrich-Wilhelm-Murnau-Stiftung that were released on home media through Universum Film. Many remain safely in-print. Others are not. After trying to find the Zur Chronik von Grieshuus DVD, I searched for the similar DVD edition of Arnold Fanck’s Im Kampf mit dem Berge (1921). I wrote about that film some time ago. I own the CD edition of the original orchestral score by Paul Hindemith (released by RCA in 1996) but hesitated over the DVD. Surely, I thought, a Blu-ray edition would be released? Nope, nope, and nope again. Now the only home media edition on DVD is long, long gone. Just as Huppertz outshines Gerlach, so Hindemith outshines Fanck. Both these respective restorations have been broadcast in HD on the Franco-German channel ARTE, and it is through off-air recordings that I have watched them. But I resent sifting through impermanent online sources to find these things. I’d really rather have the DVD.

My roundabout way of discussing Zur Chronik von Grieshuus shouldn’t put anyone off seeing it. As a film, it’s very nice to look at – and to listen to. The pleasures it offers may be (as I have said) lacking in emotional depth, but they are nevertheless reasons to watch. A well-made, well-presented, well-acted film should be celebrated. (There are plenty of films which fall short in any/all these facets.) Regardless of its more famous rival Ufa productions of the mid-1920s, Zur Chronik von Grieshuus deserves to be seen and heard for its many merits. Will someone please (re)release it on home media?

Paul Cuff