This week’s film has been sat on my shelf for a few years, and I decided to watch it because of a passing reference in a book I was reading. This was the final volume of Sergei Prokofiev’s diaries, which cover the years 1907-1933. I will certainly be writing a post about these amazing books, since they contain many fascinating references to films and filmgoing in this period. Prokofiev was a keen filmgoer, but very rarely notes the exact titles of what he has seen. An exception is Oblomok imperii [Fragment of an Empire], which the composer worried was too provincial a film to be shown outside Russia. Though this comment is hardly an endorsement, it reminded me that the Flicker Alley DVD/Blu-ray edition of the film remained in its wrapper. A few days later, I unleashed it from its cellophane and put it to work…

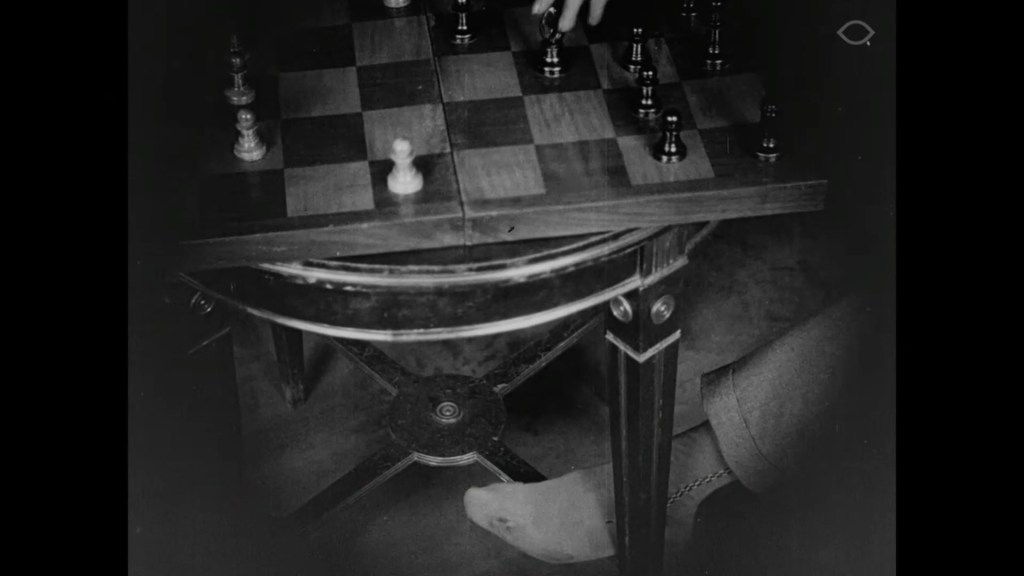

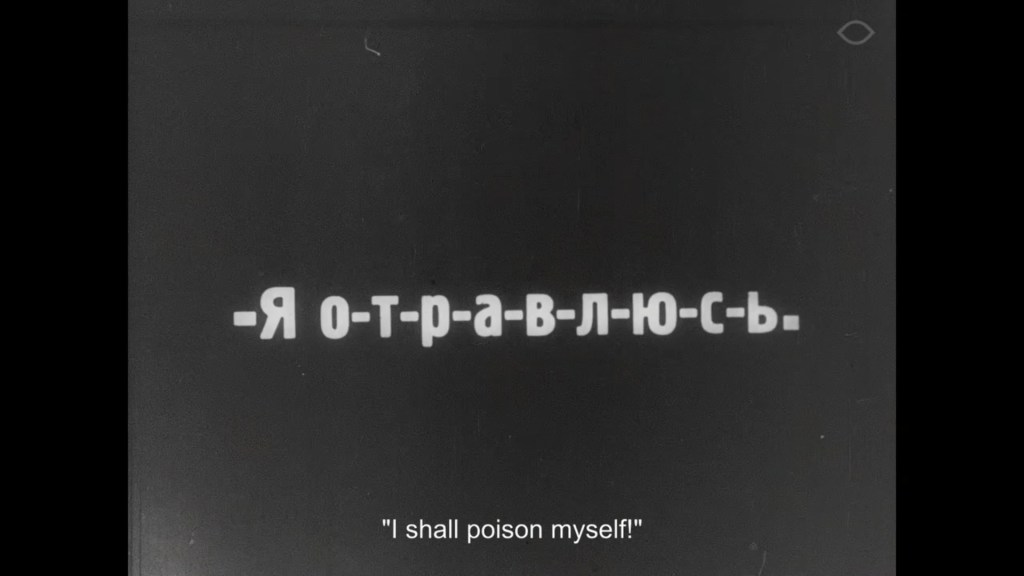

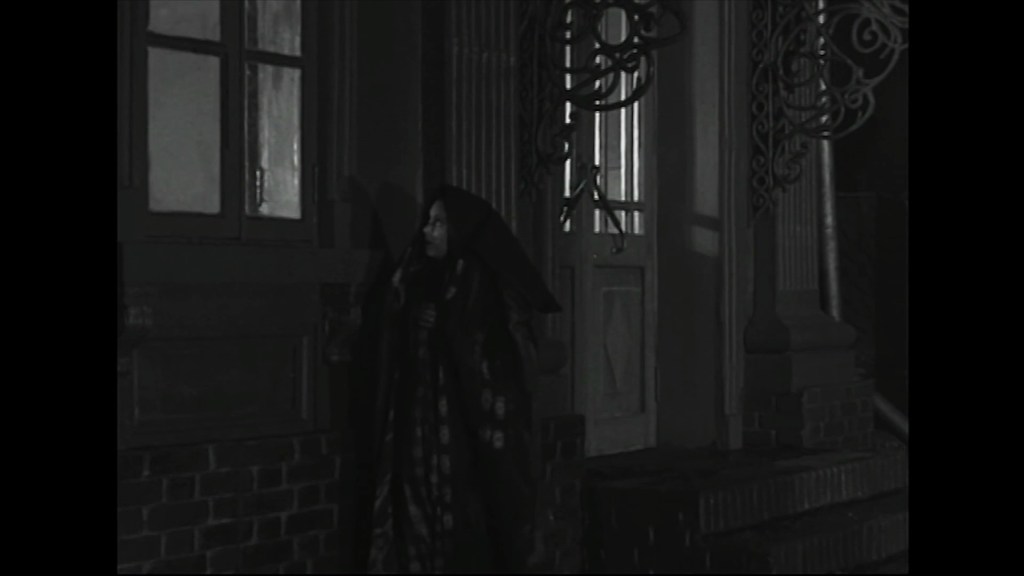

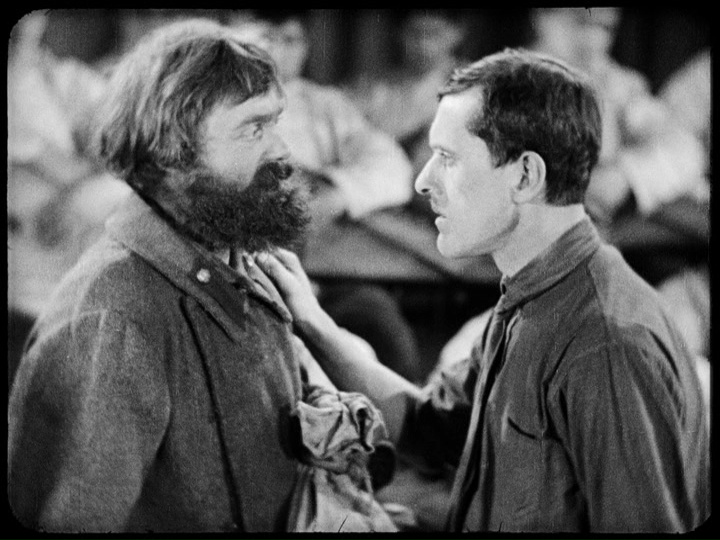

During the Great War, non-commissioned officer Filimonov (Fyodor Nikitin) suffered severe shellshock and lost his memory. A decade later, he lives in isolation in the countryside near the old front line, knowing neither his own name nor what has happened to his country since 1917. One day he catches a glimpse of his wife (Liudmila Semionova) on a passing train. This triggers a partial return of his memory, which is further restored by other reminders of his wartime trauma. At last remembering his name, he decides to leave the country for the city and find his home. Journeying back to (what was St Petersburg but is now) Leningrad, Filimonov is overwhelmed by the material and (especially) socio-political changes of the world he knew. Bewildered and alone, he finds help from a former Red Army soldier (Yakov Gudkin) whose life he had saved during the war. At a new factory, Filimonov slowly embraces the Soviet way of life – and re-encounters his wife, who had long thought him dead. Though she has remarried a pompous cultural worker (Valerii Solovtsov), she is clearly unhappy – and Filimonov looks forward optimistically to the future.

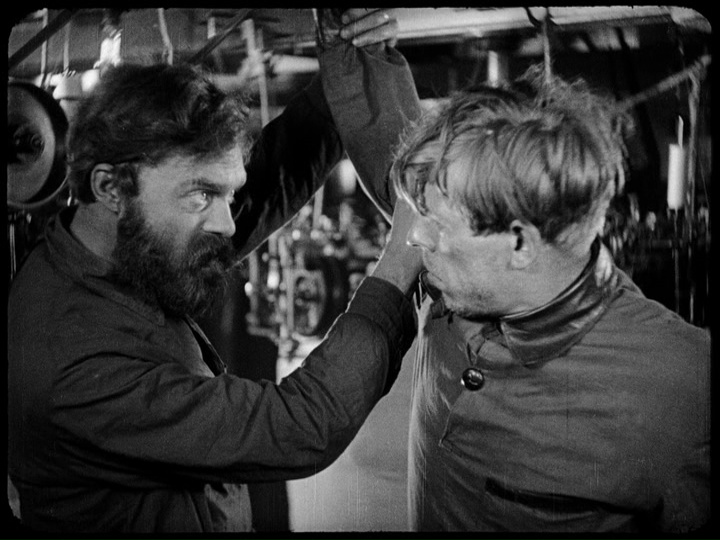

Though Fragment of an Empire is a work of propaganda for the state, it focuses its themes through a remarkable portrait of one man’s subjective trauma. Fyodor Nikitin is the heart of the film, and his performance is one of the most astonishing in Soviet cinema of this era. I found his vulnerability and tenderness (especially in the early portions of the film) absolutely heartbreaking, just as his bouts of violent hysteria are genuinely frightening to watch. When he is in the factory, more and more confounded by the attitude and organization of the workers, he repeatedly screams: “Who is the master?!” Caught in a medium close-up, his arm raised above and behind his head, his face contorted with insane confusion, Nikitin is simply terrifying: at once contained by the frame and threatening to smash it to pieces. (God how I want to see this on a big screen!) I’m not surprised to read that Nikitin seemed to become genuinely unhinged on set, with Ermler supposedly having to threaten him with a pistol to coerce him back under direction. I can hardly remember so vivid a performance of emotional trauma, nor one that – even at its most furious – is always somehow sympathetic. Even when he is screaming and raging, this man is pitiable, vulnerable. He is surely one of the most human, and humane, figures in early Soviet cinema.

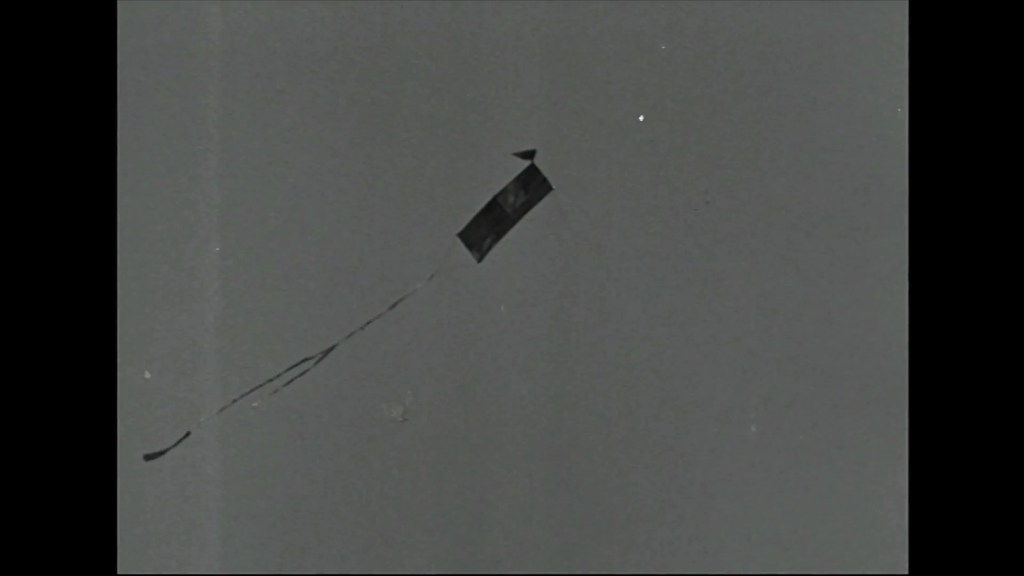

Of course, Nikitin is placed in the middle of an absolutely extraordinary series of scenes and images. The early scenes in which we glimpse Filimonov’s returning memories contain some amazing moments. I love the images of the frontline at night. Spotlight beams crisscross the black expanse of no-man’s-land, and two soldiers from opposing sides slowly approach one another. It’s an image of startling, surreal intensity. The richness of the film’s restored image – those impenetrable blacks, those searing highlights – makes such moments all the more effective. Of course, the famous (and famously censored) sequence of the gasmask-adorned crucifix is just as strange and unsettling, but it is part of a rich, dreamlike landscape of monstrous images. The way the enemy later appears with the train, likewise silhouetted in the harsh beams of spotlights, is just as nightmarish. And the scene in which the wounded soldier suckles from the dog, and the desperately poignant close-ups of man and beast, are simply astonishing. The war appears as a series of terrifying vignettes cut into the darkness, a darkness both real and metaphorical. These scenes are flashes of memory, of trauma, from a history that is too vast and too overwhelming to remember – or to see – in its totality.

Elsewhere in the opening half hour of the film, Filimonov’s involuntary flashbacks are dazzling – quite literally dazzling, since the rapid cutting between evocative images is a shock for our senses, too. I love the sewing machine than turns into a machinegun, and the way Filimonov seems to generate the very montage of the film with his manic turning of the wheel. But I think that when this sequence eventually morphs from a subjective memory to an outright lesson in propaganda (cutting between the two officers from either side demanding their men fire on the two figures), the sequence loses its edge. Setting out to emphasize the inhumanity of the officers on both sides, it loses rather than gains emotional depth. And while the cutting between spaces and people is complex, it doesn’t have the same poetic motivation as the earlier memory flashes: it has become an exercise in intellectual montage. Compared to the similar sequence of the laughing gas in Dovzhenko’s Arsenal (1929), in which there is likewise a scene of officers threatening their own men, Ermler is less hallucinatory, less strange. By the end of Dovzhenko’s sequence, we seem to have lost touch with a continuous reality altogether. Unlike the growing nightmarishness of the gas sequence in Arsenal, Ermler’s combat sequence becomes all too comprehensible.

Likewise, the scene in which Filimonov demands, screaming, to know who the “master” is ends with a long montage sequence that tries to answer his question. We see a kind of cross-section of Soviet Russia, its workers and fighters and factories etc. It is impressive for its leaps between similar images (wheels, cogs, hands etc) but it really doesn’t have an argument. It’s a kind of statement of might that just gets more insistent, not more complex or convincing. When it ends and the worker asks Filimonov (and, by extension, us) “Understand?”, we cannot answer: there is nothing to understand. The rapid montage hasn’t made an argument or an effort to answer our question, it’s simply given us a slap. Filimonov – the focus slowly pulling from the background of the factory to his face in the foreground – is breathing heavily and dishevelled, but he starts to grin. Though the film would have us believe he has now finally woken up to the marvels of his new life in this new reality, he resembles a man who has not so much found his sanity as fully embraced his insanity. His grin turns into a laugh, and he hurls himself at his comrades, kissing and hugging them like… well, like a madman. Everyone is so nice to him, and he looks so ecstatically happy, that the scene works – but the pleasure it gives in showing Filimonov released from his torment is (for us, a century later) tinged with a different kind of emotion.

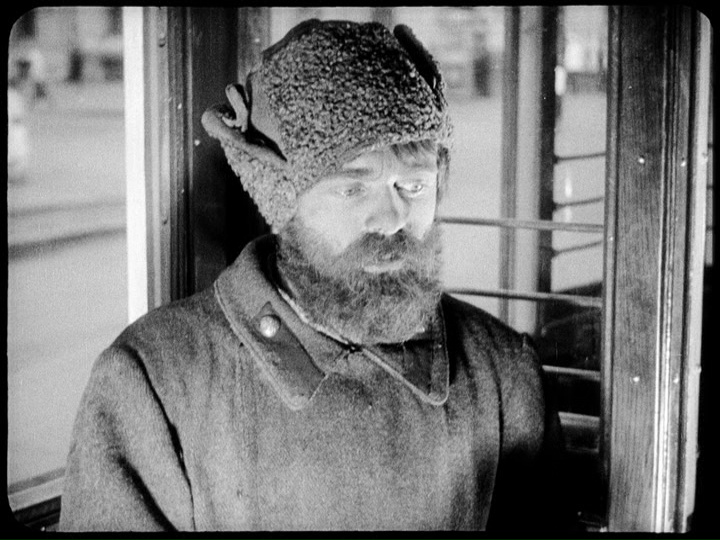

This sense of ambiguity is part of the film’s fascination. While Ermler offers some superb sequences and images, the film is often so convinced of its own effectiveness as propaganda that it simply overlooks the possibility that we might think differently. Our sympathies – especially as viewers nearly a century later – are liable to wander from the official line. Filimonov’s questioning of the Soviet world might encourage us to question it too. And the more he becomes convinced by this new world, the more he becomes a different person. His final line, which is also the final line of the film, is delivered straight to camera: “We still have a lot of work to do, comrades”. Immediately following the violent altercation between Filimonov’s ex-wife and her husband, there is an implication that personal change must accompany social change. But with Filimonov himself, this change is also a loss. The way he now appears before us – his beard neatly trimmed, his clothes neatly worn, his hat neatly fashionable – makes him a different man than the one who initially went in search of his wife. He resembles the other workers, the men and women he had found so alien and threatening, and he now echoes the way they speak. Yes, he has grown up, he has awakened, he is no longer hysterical. But there is a nagging sense that something else has happened. It is as if Filimonov has been uncannily replaced. This new Filimonov is a sinister doppelganger of the man we used to know. His last line is both an encouragement and a threat.

Part of this weird emotional effect is due to the original music by Vladimir Deshevov, as transcribed for piano in this recording by Daan van den Hurk. There are some superb sequences of sound and image interacting, often in ways you don’t expect. Take the early flashback sequence in which we see the Russian soldier praying before the crucifix. Visually, the image of Christ wearing a gasmask is jarring and surreal. Illuminated against the dark night sky, this figure of compassion becomes one of threat. But the soldier prays anyway, and Deshevov’s gorgeous, slow chorale throughout the start of the sequence gives a powerful sense of pathos and pity. If the image of the tank crushing both crucifix and soldier ends the scene with a grim punchline (demonstrating both the lack of mercy in war and a lack of religious authority to protect), the preceding music deepens the empathy we feel. As throughout, the score provides a degree of humanity that the images either cannot quite achieve or deliberately do not wish to achieve.

When Filimonov emerges from the tram onto the streets of Leningrad, his absolute disorientation is made the subject of bursts of rapid montage, mobile camerawork, and a delirious repetition of images. Deshevov’s music is like a kind of panic attack in sound, with its repeated, threatening, bustling, grandiose, rising progressions. The sequence is the first of many times that the film seeks to show off what has been achieved by the Bolsheviks while Filimonov has been away. But what the music does is make this very act of showing off almost terrifying. It is too upbeat, its tempo too rapid, to offer anything in the way of comfort or consolation. It is alienating rather than accommodating. This music makes you feel pity for Filimonov’s confusion, the confusion of a man as yet unconverted (and unconvinced) by Soviet Russia. The effect of alienation becomes ours as much as his.

There are later iterations of this kind of “look what we have achieved!” montage. They culminate in the above-mentioned sequence in which the worker demonstrates (via the grand montage) where the “master” is. The dense chromaticism of the music becomes almost unbearably tense, and resolves not in a complex transformation but in a sudden full stop (accompanied by the cut to black that ends the montage). There then follows a passage of scampering, major-key jollity, interjected with an almost religiose chorale motif, that is as weirdly unsettling as the preceding chromatic tension. It’s a brilliantly odd, unexpected way of ending this scene of conversion.

The fact Deshevov’s score seems subtler, wilier, than the film made me curious about the origins of the music and the man. Deshevov (1889-1955) was the same generation as his more famous compatriot Prokofiev, but unlike the latter he remained in Russia throughout the Revolution. Like Myaskovsky and Prokofiev (and their younger compatriots Popov and Shostakovich), Deshevov became part of the mainstay of Soviet composers who worked under the increasingly strict guidelines meted out by Stalin. He would compose much orchestral music (including several ballets), as well as chamber work and piano music. Ermler’s commission to write an original orchestral score for Fragment of an Empire was a rare instance of collaboration between a major director and composer in this period of Soviet cinema. Ermler was hugely impressed by the result. “I am afraid that people will go to listen to the music, not to watch the film”, the director told Deshevov in 1929. “So be it! I am delighted.” Yet the music was barely discussed at the time and remained seldom heard since, especially because copies of the film itself were dispersed, dismantled, and/or destroyed.

The present restoration of Fragment of an Empire was completed in 2018 after a collaborative project by the EYE Filmmuseum, Gosfilmofond of Russia, the Cinémathèque Suisse, and the San Francisco Silent Film Festival. From what I can glean, the new restoration was presented with Deshevov’s orchestral score for the first time in October 2018 at the Mariinsky Theatre in St Petersburg. Per the programme notes for this performance, the score was restored using “the set of orchestral parts retained in the theatre’s library” by composer Matvei Sobolev. Deshevov’s score was performed again at Pordenone in October 2019 with Günter A. Buchwald conducting the Orchestra San Marco, Pordenone. The essay for this festival screening details the history of how Ermler commissioned Deshevov and the subsequent neglect of the music. (Sadly, this essay does not clarify if the 2019 performance used the same musical edition prepared by Sobolev in 2018 – but my assumption is that it did.)

Yet the Flicker Alley release from 2019 confuses this picture. The blurb on the back of the DVD/Blu-ray box states: “The film is accompanied by a choice of two musical scores: a brilliant new score composed and performed by Stephen Horne and Frank Bockius, and an adaptation of Vladimir Deshevov’s original piano score performed by Daan van den Hurk.” It’s curious, but I suppose understandable, that the modern score takes precedence over the original. But why refer to the latter as the “original piano score”? Isn’t this a piano transcription of the original orchestral score? Flicker Alley make it no clearer within the booklet for their release, since the credit section therein refers to “Vladimir Deshevov’s original score” being “adapted and performed by” van den Hurk. Van den Hurk’s own statement in the booklet refers to Deshevov’s other compositions for solo piano and the film score being “a worthy piano concert piece”. But on the very next page, Stephen Horne and Frank Bockius refer to van den Hurk’s work as “a piano transcription of the original score”. This, surely, is closer to the mark. But neither here nor anywhere in the Flicker Alley release is it mentioned that Deshevov’s music was written for and performed by an orchestra in 1929. Nor is there any acknowledgement that this orchestral score had already been restored and performed with the 2018 restoration of the film. (Even the audio commentary soundtrack on the Flicker Alley release, I note, uses the modern score as its background music, not Deshevov’s – further evidence of how his score is subtly deprioritized on this release.)

So what are we listening to on the Flicker Alley soundtrack? Since the wording is so vague – deliberately so, it seems to me – throughout the release, I’m not even sure if van den Hurk’s work was a transcription of Deshevov’s orchestral score or based on a piano reduction prepared by the composer or another contemporary musician. Even if it was based on a piano version by Deshevov, this does not entitle it to be called or understood as the “original score”. Some context is required here with these terms. For example, Deshevov’s contemporary Prokofiev began most of his compositions on the piano, even if they were to end up as orchestral works. When he was working on ballets, he would often suspend work on finishing orchestration to produce a piano transcription for the sake of his stage performers. In advance of their productions, Prokofiev’s collaborators would need a sense of the overall structure (and timespan) of the music in order to build the choreography, prepare the staging, and begin rehearsals. Several of these transcriptions exist, but even if some or all of this music for piano predates the final orchestrated version, this does not mean they should be understood or received as the “original” scores. In the case of Deshevov’s music from 1929, he may well have written some of the score for piano before orchestrating it. But to advertise this as the “original score” would be to entirely misunderstand the nature of composition and performance practice. The orchestral version is the original score, no matter if it was the end result of a complex process of drafting, redrafting, and instrumenting. But all this can only be supposition, since Flicker Alley do not offer any details about this process of “adaptation” – and never once admit that Deshevov’s score for Fragment of an Empire was written for orchestra.

Why should we care about this? Because finding out information about silent cinema, especially silent film music, is already difficult enough. Original materials and resources are difficult to find and difficult to interpret, so it is vital to be honest and transparent about all aspects of restoration. I try always to bear in mind (and be honest about) the factors that have shaped the way I see silent films, especially on home media. All too often, however, marketing muddies the waters. It directly impacts how silent films are received by new audiences and new scholars. Of all the information available online or elsewhere, it is the DVD blurb that gets endlessly repeated. When the Flicker Alley edition of Fragment of an Empire won a well-deserved prize among Il Cinema Ritrovato’s DVD Awards in 2020, for example, the release is credited as offering “the recreation of Vladimir Deshevov’s original piano music from 1929”. This text hasn’t been generated by Chat GPT, but by the human curators of a prestigious festival. What hope have the rest of us if misleading information just gets copied and pasted from the marketing? Confusion, if not outright misinformation, rapidly filters through to writing on the film, which in turn generates more confusion and/or misinformation. So please, please don’t gaslight me.

I regret spending so much time writing about the accompanying text of this release. Not only is it a grand old waste of my time having to write what the liner essays should have said straight up, but it also means I have less space to talk about the music and the film. Let me be clear: the restoration presented by Flicker Alley is visually superb, and regardless of the score I am exceedingly glad to have it. What’s more, I absolutely loved Deshevov’s music, and it makes Ermler’s film all the more complex and compelling. But however good the piano transcription, I would so much rather listen to this score in its original form: for orchestra! Here’s hoping that it will be performed live in the future and, as I never tire of hoping with such things, released on home media.

Paul Cuff