Day 5: Buddenbrooks (1923; Ger.; Gerhard Lamprecht). I was very excited when I saw this on Bonn’s line-up. A new restoration of an unknown Gerhard Lamprecht film? Yes please! A silent adaptation of a Thomas Mann novel? Yes please! Lavish sets and settings? Yes please! Are you a resident of Germany, Austria, or Switzerland? Y—! Oh… no. Well, no film for me today. No Lamprecht, no Mann, no lavish sets, nor even the comfort of living in an appropriately central European country.

To be fair, I knew this was coming, having seen the dreaded asterisk on the programme that denoted access to the online version was limited by copyright according to region. As the festival’s co-curator Oliver Hanley said to me after the festival last year, there are sometimes occasions when compromises must be made. This is an exciting new restoration of an important work by a major director, so it’s clearly worthwhile being programmed, whatever limitations there are for streaming it. I don’t resent the good folk of Bonn being able to see this film in situ at the price of we folk from afar not being about to see this film online. One really can’t complain: this online version of the festival is still, miraculously, free, and there are plenty of other films on offer. At least I am now aware of the existence of the restoration of Buddenbrooks. Hopefully it will do the rounds, so to speak, and appear somewhere where I can attend or view online. So, on the fifth day I rested.

Day 6: Shakhmatnaya goryachka (1925; USSR; Vsevolod Pudovkin/Nikolai Shpikovsky). Today’s short film takes us to Russia, and to a delightful directorial debut. Pudovkin’s first film is a comic skit about the titular “chess fever” that grips the Hero and distracts him from his impending marriage with the Heroine, only for her to end up in the arms of chess champion Capablanca and be won over to the game – and back to the Hero.

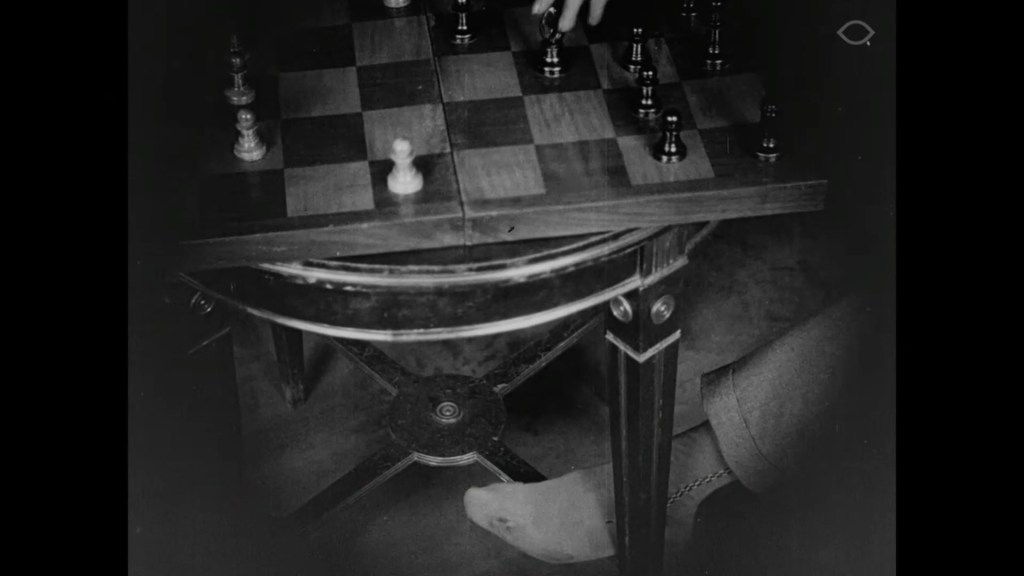

I’ve seen this film before, but so long ago that I felt like I was discovering it for the first time today. I’d forgotten how packed with marvellous gags it is, taking advantage of every kind of space and movement. Though Pudovkin is famous for his later propaganda films, and especially for his dramatic use of montage, Chess Fever shows his playfulness and skill exercising numerous cinematic techniques for comedy. See how the shot/reverse-shot of the feet underneath the chess table creates the impression of two players, only for a wider shot to reveal a single player with mismatched socks swapping sides to play against himself. Or the brilliant use of reverse-motion when the Hero is irresistibly drawn backwards down the pavement into the chess shop. Then there is a deliciously Keaton-esque snowballing of gags when the Hero has his books of chess problems thrown out of the window. An officer arrests a man for stealing a ride on a bus, but is distracted by the unexpected arrival of the chess problem from above. We have already seen other people being pleased to find these papers rain down on them, but here the gag is developed. The film cuts from the distracted officer and the man he’s supposed to be arresting to a shot of another bus. We see another bus passing by, and one, two, three, four, five men clung to the side. This looks like the climax to the gag, but the film delivers one final, knock-out gag: behind the bus is an entire line of punters who have affixed a rope to the bus and are sliding along behind it.

The titular “chess fever” of the film is everywhere. Not only does everyone reveal themselves to be a fanatic, but the feverishness becomes embedded in the patterns on screen. The chess board’s chequer pattern is everywhere about the Hero’s person: his sock, hat, scarf, handkerchief. And this pattern is everywhere around him, too, from the floor tiles that the Hero finds himself moving across like a chess piece, to the series of ever-tinier chequered items of merchandise and apparel that the Hero jettisons in the river. The tiniest board is kept for last, however, when – having thought he had lost all his chess sets and now cannot play with his converted bride – he remembers his emergency set kept in a pouch around his neck. He withdraws this absurdly small board, and the lovers play micro-chess before passionately embracing.

As a side note, I also enjoyed the cameo from the real chess champion José Raúl Capablanca. As it happens, I’m reading Sergei Prokofiev’s diaries at the moment. Prokofiev was a chess fanatic and befriended Capablanca in his teens in St Peterburg, before the Revolution. In fact, Prokofiev actually played and beat this future world champion in 1914 during a chess championship. For this reason, it was delightful to see the opening close-up of Capablanca, looking a little playful, a little awkward, a little amused. (Rather appropriately, my writing of this paragraph was interrupted by the postman, who has just delivered my latest Prokofiev purchase: the sadly out-of-print 1960 recording of Semyon Kotko, which is, I’ll have you know, ladies and gentlemen, the only uncut recording of this opera currently on the market.)

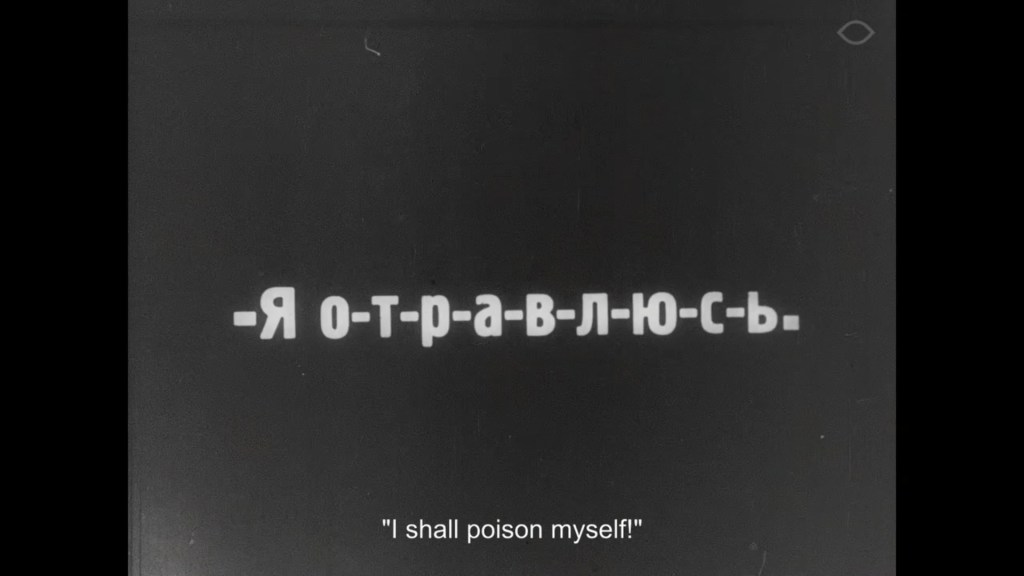

The music for this presentation was by Sabrina Zimmermann and Mark Pogolski on piano and violin. This was tremendous fun. Full of life, wit, melody, irony, and energy. I loved the citations of La Forza del destino when the Hero finally arrives, late, to his fiancée’s side – and later when the Heroine goes to buy poison to end her own life. The operatic behaviour of the characters is itself a kind of parody of the fatalistic Russianness of pre-Soviet cinema à la Evgenii Bauer et al., and the music lives up to the bathos. Throughout, the score kept pace with the film’s sudden shifts in gear, changes of tone, and slights of hand. Though only 25 minutes long, the film demands dozens of swift manoeuvres from any accompanist. Zimmermann and Pogolski produced a little gem of a performance, fully worthy of the film. This soundtrack was recorded live, and I enjoyed hearing the murmur of distant laughter. It wasn’t so loud as to be distracting, but just enough to make me feel I was sharing part of the performance.

What else to say? This is a brilliant film, presented here with a perfect musical accompaniment. Whatever disappointment I had over missing Buddenbrooks was swiftly forgotten in the pleasure of seeing Shakhmatnaya goryachka in such a great performance. Bravo!

Paul Cuff