The “100 Years of Film Music” series was issued by BMG/RCA Victor Red Seal across twelve CDs in 1995-96. This series is impressively eclectic, and it makes a rather strange cross-section of film music. Five of these CDs are devoted to silent film music of various kinds. Original music from the era includes Paul Hindemith’s complete score for Im Kampf mit dem Berge (1921), Hans Erdmann’s score for Nosferatu (1922), extracts from Chaplin’s music for his silents (1921-36), and Paul Dessau’s music for various short films (1926-28). (Among these recordings, the Gillian B. Anderson arrangement of Erdmann’s score is perhaps the most unique in being unavailable elsewhere. Her edition is closer to Erdmann’s original orchestration than the edition that accompanies the film on any home media release.) Additionally, there is one set of modern scores for silent films in this series by Karl-Ernst Sasse, composed for two Lubitsch films in the 1980s (about which I will dedicate a post in the future). The series also includes a recording of Charles Koechlin’s The Seven Stars’ Symphony (1933), a piece inspired by cinema but never used to accompany films of the era. Altogether, a very curious blend of the old and new, the real and the imaginary.

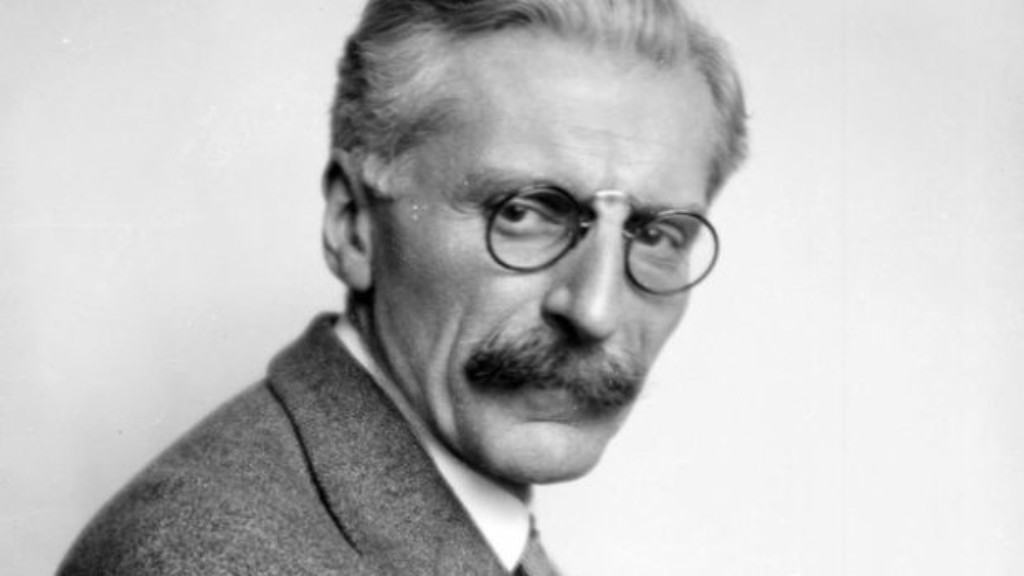

All of which brings me to Paul Dessau (1894-1979). This prolific composer is most famous for his operas and large-scale works written in the post-war period, where he worked in East Germany. However, he began his career in the 1920s as a cinema musician – first in Hamburg, then in Berlin. In Berlin, a relative of his owned the Alhambra Theatre and recruited Dessau to work as part of the cinema orchestra there. From being a violinist, he swiftly became an arranger and composer of music for silent films. The process of composition was amazingly rapid. The afternoon before new material was shown in the cinema, Dessau would watch the film(s) and make notes of the timings of the action on screen. That evening, he composed the music and gave this material for the copyists to write out the parts for the small orchestra (usually 12-15 musicians). The next day, Dessau would lead the orchestra in rehearsal in the morning, then in live performances for the public that afternoon and/or evening. This hectic pace of music-making stood Dessau in good stead. By the sound era, he had made a name for himself as an important new composer – but continued his role for the cinema. In the early 1930s, he contributed music to the soundtracks of Arnold Fanck films, and later in the decade to the dramas of Max Ophüls. He also arranged music for films by Lotte Reiniger and the operetta films of Richard Tauber, moving freely between avant-garde modernism and popular operetta.

But how much of his silent film music survives? I wrote recently about his scores for Saxophon-Susi (1928) and Song (1928), lamenting that neither was extant and regretting the lack of any information about their style or content. In the wake of these pieces, Donald Sosin recommended that I chase down the CD of Dessau’s music on the “100 Years of Film Music” series. This CD features Dessau’s music for four short Disney cartoons from 1926 and one half-feature length animation by Władysław Starewicz from 1928. The edition features Hans-E. Zimmer (no, not that Hans Zimmer) conducting the RIAS Sinfonietta, and it is marketed as a “world premiere recording”. In order to properly gauge how this music worked, I needed to find the films. Thankfully, I found that the Starewicz film had already been restored with Dessau’s music and broadcast by ARTE in 2004 – and a video was available online (after a little searching). The Disney films posed more of a problem. I found three in decent quality online and set about synching the music to their images. (This quickly revealed that the music was recorded without the timings of the films available or in mind.) After much fiddling and repeated exporting to new video files, I was able to sit back and watch everything through…

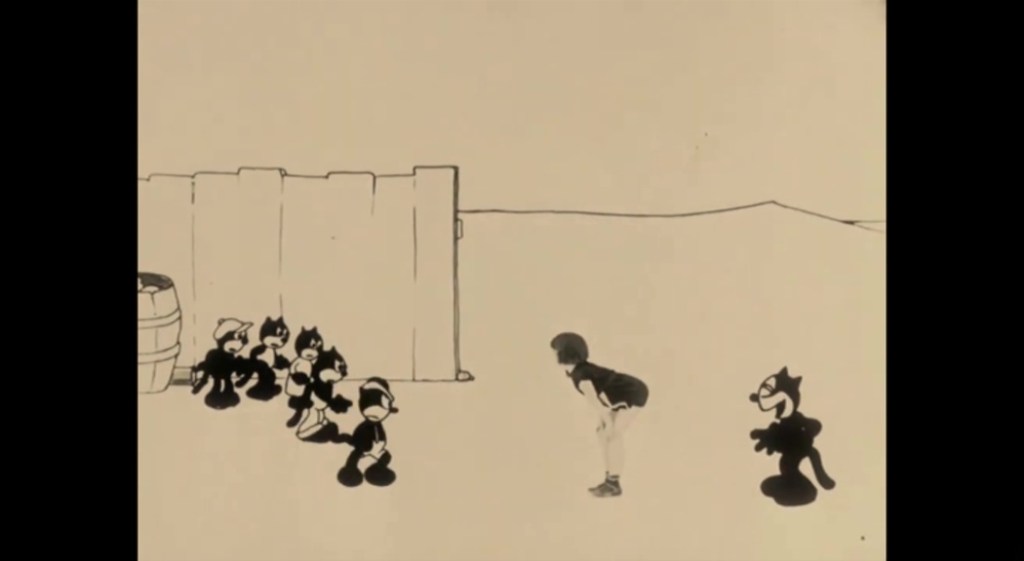

So to our first set of films. These are part of Walt Disney’s “Alice Comedies” series, mixing (mostly) animations with (occasional) live action. The lead cartoon character is ostensibly Alice (played in these films by Margie Gay, one of several children to don this role), though really the adventures are dominated by the character of the cat Julius. (Julius deliberately echoed the design of Felix the Cat, designed by Disney’s rival animators Otto Messmer and Pat Sullivan.)

In Alice in the Wooly West (1926; US; Walt Disney), Julius fights the outlaw Pete, a bear who robs stagecoaches and harangues the local population. The film is utterly charming, filled with beautiful touches. The designs might seem relatively simple, but the animation is a riot of brilliant details. Further, it’s incredibly witty about the limitations and possibilities of its medium. Characters can climb nimbly into the air, sidestep across space, crawl across dimensions, remove and interact with their own skins, be blown apart piecemeal and reconfigure themselves… Dessau’s music interacts with this world in wonderful ways. Engaging with the (by 1926 already long-familiar) Western genre, Dessau summons a familiar soundscape of military marches (both British and American) and whip-cracking percussive effects. But he renders these musical elements unfamiliar through his harmonies and orchestration. The usual brassiness of a band or orchestra is thinned for a theatre ensemble, reduced to odd combinations, or rendered spiky and weird by odd rhythms and changes of pitch. Musical pastiche and parody are perfect accompaniments for the film’s playful mobilization of cowboy tropes. When Julius has defeated his foe, Alice arrives and calls him her “hero”. Dessau accompanies this moment with the first bar of “The Star-Spangled Banner”, which immediately lurches into a manically rapid flourish and fanfare for the film’s end. There is no loyalty to tunes for too long, nor to their attachments of nation or ideology. Melodies are summoned as material to be whipped into new shapes, then jettisoned. It’s a score as quick on its feet as the film.

Alice the Fire Fighter (1926; US; Walt Disney), as the title implies, concerns Julius and Alice battling a fire in a tall hotel building. Dessau fills the film with scurrying motifs and mechanical rhythms. There is a bell and sleigh bells to synchronize with (some of) the fire bells and engines on screen, but the orchestra itself takes on the numerous repetitive rhythms that match the identical (and identically-animated) ranks of horses, cats, and engines of the fire brigade. These motifs are also anxious, high-pitched, restless forms that scurry along in accord with the urgency of the action. Yet there are moments of pure delight, when both film and music deliver delicious little gags that act as vignettes within the action. My favourite is the moment when the little dog rescues his upright piano from the burning hotel. At first we hear a tense refrain for woodwind, with occasional dim clashes of cymbals, as he pushes it out the door and over the porch. A mouse on the top floor waves to him for help. The pianist on screen plays his piano and the notes appear in the air, the scale spelled out like stepping-stones from the window to the piano. Dessau, of course, uses the piano in the orchestra to spell out an ascending scale; then, as the mice neatly run down the notes, a descending scale. But even this moment has an odd tension in it. Dessau’s scale runs are harmonically uncomforting, ending in an anxious trill (at the top) and a low sharp (at the bottom). The strands of music throughout the score are thin, shrill, weird. It makes you notice the weirdness of the film, the curious minimalism of the line drawing, the wit and precision of the characters. Indeed, I feel that it’s an impressively tense piece of music for so slight a film. It’s endlessly moving, picking up the next idea – a kind of perpetual self-invention. So many of the motifs last barely more than a bar or two – such as the delicious rustic march, all jingling and banging, that accompanies the fire brigade’s initial effort to extinguish the fire – and later reappears as Julius rescues the lady cat. It’s such an irresistible little motif but lasts only a few seconds. And for the cats’ climactic embrace there is an amazingly long-running crescendo in the strings, followed by a final burst for brass of “Hoch soll er leben” (a traditional German celebratory tune). It’s all over in a flash, but what a brilliant flash it is.

Alice Helps the Romance (1926; US; Walt Disney) concerns Julius’s efforts to woo a girl and defeat his rival in love. It begins with a delightful passage for clarinet and banjo, as Julius strums away on screen, then preens himself to impress his lady friend. But this light-hearted insouciance doesn’t last, and the music quickly turns acerbic and ironic. Julius is outsmarted by his rival and finds himself rejected and alone. As in Buster Keaton’s Hard Luck (1921), our hero in Alice Helps the Romance repeatedly tries to kill himself, each time via different means. As Julius wanders dejectedly in a state of aggrieved loneliness, mocked by birds and thwarted in his suicide, Dessau provides some incredible little passages of anxious woodwind instruments circling one another. It’s appropriate for a film that has such bleak elements to it. A solution to Julius’s heartbreak is presented when he hires a small gang of youthful roughs to surprise his rival when he is with the girl. The gang of kittens approaches the rival while he is snuggled up with the girl. They stop and bellow “Papa!” in chorus. Dessau renders the syllables of “Papa” into a throaty, rough-edged brass call. This moment perfectly echoes the scene in Act 3 of Richard Strauss’s Der Rosenkavalier (1911), when a disguised Annina claims that Ochs is her husband and the father of her numerous children. A small crowd of the latter flock around Ochs, crying out “Papa! Papa!” in the same ascending, two-note phrase used by Dessau. The moment works perfectly in the film, the orchestration giving its humour an aggressive edge. But it’s also a delightful citation of “high”, adult culture in the context of this knockabout cartoon for children.

Finally, there is also Alice’s Monkey Business (1926; US; Walt Disney), but alas I could not find any copy of this film to watch with the music. (At least one source states that the film is lost.) Swirling woodwind, plodding marches, scraping strings, filigrees of flutes, scampering piano, rambunctious brass – it’s a weird jungle of sound. Listened to without images, you really get a sense of how intricate this music is – and how well it conjures a narrative. I do hope the film survives somewhere…

So to the longer film: L’Horloge magique (1928; Fr.; Władysław Starewicz). Produced by Louis Nalpas (the man who oversaw Abel Gance’s early feature films), this 40-minute film was the creation of Władysław Starewicz. Born in Russia to Polish parents, Starewicz (also spelled variously Starevich, Starewitsch, Starevitch) produced dozens of animated films from the 1910s into the 1960s – working initially in Russia, then (after the Revolution) mainly in France.

The framing story of L’Horloge magique shows Bombastus, the inventor of an elaborate mechanical clock, and the young Yolande, who dreamily watches the story its figures tell… In a medieval kingdom, the King seeks a knight to defeat a dragon and prove himself worthy of his daughter, the Princess. When the knight Betrand kills the dragon, he appears to win favour – only for the sudden apparition of the Black Knight to send the Princess into a torpid spell. The King’s advisors concoct elaborate schemes to bring the Princess back to health, and the knights set out to battle the Black Knight. As the bodies of the failed knights pile up, the Princess falls for the Minstrel who sings to her as she recovers. The jester informs both Betrand and the King that the princess is busy with the Minstrel. Betrand seeks out the Black Knight, who is revealed to be a fire-eyed figure of Death. At the climactic moment of their fight, a terrified Yolande breaks the clock. Distraught, at night she dreams of a fairy realm, where Sylphe (in the woods) and Ondin (in the water) are rivals in the natural world. Yolande dreams of the enchanted forest, where the trees berate her for wounding the plants and insects as she walks. Shrinking to miniature size, Yolande flees the plants who come to life. A giant appears and wounds Yolande, who is found by Ondin – while Sylphe finds the discarded Betrand and his horse. Between the two, they revive the knight and Yolande, who are guided to one another by the flowers and mushrooms. When Yolande (“this daughter of Eve”) is tempted by a giant apple, she is attacked by a serpent – and rescued by Betrand. In the real world, Yolande stirs in her sleep. FIN.

L’Horloge magique is a quite unbelievably impressive blend of live action, puppetry, and stop-motion animation. This delightful, weird, disturbing, charming film is filled with amazing moments and startling images. Though my focus here is the music, I must at least record that the film itself made quite an impression on me. Aside from the elaborateness of the worlds it creates (the medieval world around the castle, then the fairy world in the wild), it is magnificently directed. To pick just one device Starewicz uses, I loved the way the film recreates the effect of a moving camera, pushing closer to the action. Since this, too, is achieved by stop motion, the result is startingly rapid. These moments are almost like crash-zooms into the middle of the scene. My favourite such moment being after the prospective knights are introduced. Starewicz ends the scene with one of these sudden movements into the scene, accompanied by a fade to black – timed so that it seems we are disappearing into the dark maw of the palace, whose gate has (with equal suddenness) just been opened. This is the first instance of the moving camera and it’s incredibly startling, even discomforting.

Dessau’s music makes the perfect accompaniment to all these aspects. Passages of slow, anxious strings introduce us to the outer world of Bombastus and Yolande. It’s like the music is feeling its way into the narrative, just as we are being drawn towards the story-within-a-story. Only when the mechanism of the magic clock – the first use of stop motion – comes to life does the piano, followed by woodwind and percussion, join the strings. Just as the magic world of the toys comes to life, so does the orchestra. Yet the soundworld here never relaxes, never seeks to comfort us.

So many details in the harmonies and orchestration behave in ways you don’t expect. Even Bertrand, the valiant knight, gets an oddly sparse introduction. And his killing of the dragon is followed not by fanfare or bombast, but by silence for the Princess’s applause, and an odd, descending motif for solo violin. The music seems to warn us that nothing is resolved, that nothing will – or should – go the way we expect. Lo and behold, the Black Knight bursts through the palace doors. His appearance is as impressively weird and sudden in the score as on screen. A blast of sound, densely orchestrated to resemble the gust of an organ.

Very often, Dessau’s music keeps an ironic distance from the action. This score seems faintly distrusting of the film, as though it would rather observe from the sidelines. (One can imagine Dessau being akin to the ironic jester who appears in L’Horloge magique.) Dessau divides his already small orchestra into chamber textures, deploying the full volume of his forces sparingly. This is as he did for the Disney films, but here he pushes his method further, pursuing more eerie effects. In Yolande’s dream (the second half of the film), the flute and strings suggest an aura of bucolic magic – but their uneasy chromatism captures the strangeness of the world on screen. Sylphe and Ondin are sinister sprites whose motives we never quite trust. Is violence ever far away? This is a world of walking trees, writhing beetles, crushable butterflies.

But it’s also very beautiful. Listen how the music slows, and woodwind and strings climb into strange, high registers – as when Sylphe mourns the death of a beetle, examining its remains with pity and fellow feeling. And there are moments of intense excitement, as when Ondin and Sylphe rush headlong at one another, the whole orchestra coalescing into a torrent of repeated motifs. Then there’s the outrageously beautiful sequence of living flowers. Dessau uses a gorgeous solo violin in a passage as deliriously seductive as the flowers, which offer their perfume “filled with love” to intoxicate and inspire Yolande. Starewicz uses dreamy, swirling, multiple superimpositions, just as Dessau uses a dreamy halo of strings.

The film’s finale begins with a stunning image of the serpent uncoiling itself against the sky to strike Yolande, whereupon Dessau’s music races along to the rescue with Betrand. But it’s in the union of the couple that Dessau is at his most sharp and surprising. As the couple sit on the giant apple together, Starewicz cuts to an intertitle: “Immorality”! It’s such a startling line, followed by a cut to Sylphe and Ondin winking and looking shocked and awkward. Dessau brings in the wheezy chords of a harmonium, introducing what might be a religious ceremony – or even a religious condemnation. But the slow chords of the harmonium are interrupted by a decidedly irreligious volley from the orchestra. This single phrase, at once banal and catchy – a kind of dah-dah, dah, dah-dah! – sounds like the start of some swinging, music-hall style number. The tone is wonderfully odd, at once sinister and silly. It matches the film perfectly, since the “lovers” – in live action form – are barely older than children. Yolande and Betrand greedily bite into a chunk of bread, which they share with the horse. Betrand has tinsel-silver hair and talks with his mouthful, motioning to the kissing sprites. It’s a childish fantasy, an innocent end to a frightening tale. The last shot of the film is Yolande stirring in her sleep. Her finger drowsily taps out something on her chest, as though she’s spelling out the rhythm of Dessau’s music.

In sum, I found this music – with these films – exceedingly engaging and rewarding. The DVD editions of Disney’s “Alice” films thus far have often been marketed (understandably) at children, including a recent release in France. But Dessau’s music is decidedly adult. It highlights, the wit, the humour, and – above all – the strangeness of these films. The fact that Dessau’s soundworld for Disney is so close to his soundworld for Starewicz demonstrates a curious continuity between the films. These are odd, unstable little worlds on screen – liable to break out in violent fragmentation or mend in magical resolution.

In their tone and playfulness, their mixture of original and recycled music, Dessau’s music reminded me most of Karl-Ernst Sasse’s music available elsewhere in the BMG/RCA “100 Years of Film Music” series. Like Dessau, Sasse became a stalwart of East German music, though Sasse worked primarily for television – including many televised versions of silent German films. It’s pleasing to think of the legacy of a film composer of the 1920s re-emerging in a new context in the late 1970s-80s. I will have more to say on Sasse in due course, but for now it’s worth observing the relative obscurity of their music for silent films. Though I enjoyed the challenge of synching Dessau’s music with the Disney films, I deeply that I had to do it at all. And while the ARTE broadcast of L’Horloge magique evidences an excellent restoration, this version with Dessau’s music has not (to my knowledge) been issued on DVD.

Moreover, hearing this music makes me even more keen to hear Dessau’s scores for silent feature films. As I wrote in my earlier piece (linked above), reviewers in 1928 praised the wit and inventiveness of Dessau’s score for Saxophon-Susi. I wonder how Dessau handled the longer timeframe, and how he handled the melody of the film’s titular song. Moreover, what material from this or his other silent film scores survives? Where might the music be located? For the 1995 recording under discussion here, Wolfgang Gottschalk is credited with the “restoration of [the] scores”, but the process of restoration is not described at all. How much work was needed to make these scores performable? How close does this music sound to what was heard in the 1920s? And is there more material by Dessau from this period and this genre? As ever, if anyone knows more information, do get in touch…

Paul Cuff

My thanks to Donald Sosin for alerting me to the recording of Dessau’s film music.