Day 6 takes us to Germany, or rather to a Ruritanian kingdom. Ruritania has been a theme at Pordenone both this year and last year. In 2022, I wrote about Anthony Asquith’s The Runaway Princess (1929), starring Mady Christians. This year, we get another film starring Mady Christians, directed by Fritz Wendhausen—the man credited as “co-director” of The Runaway Princess. (Since The Runaway Princess was an Anglo-German co-production, this credit is perhaps a case of the German version of the film being handled by Wendhausen.) We also get a bonus “actuality” of Balkan dignitaries from 1914 (very much along the lines of a 1912 film shown last year). So—off we go…

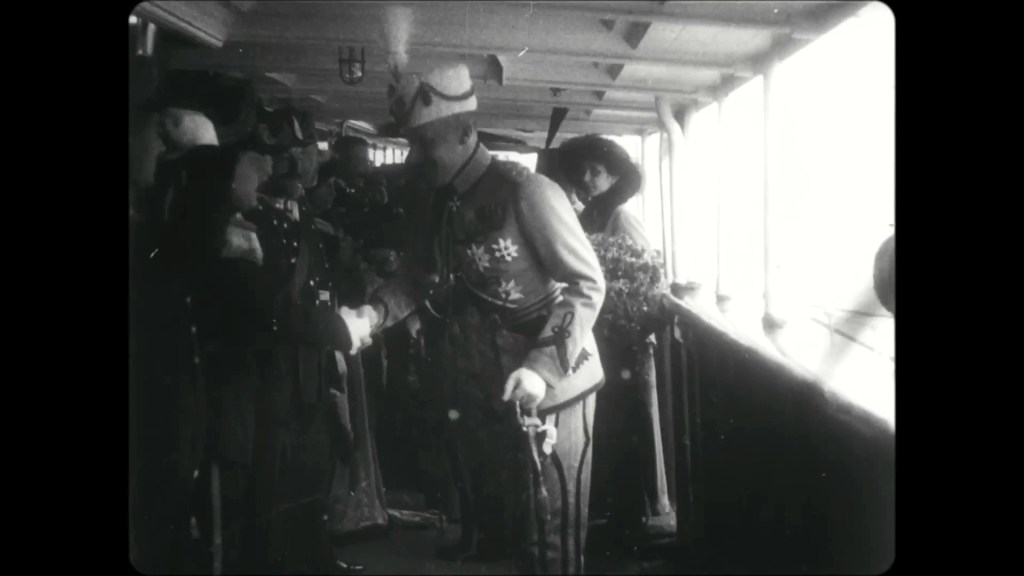

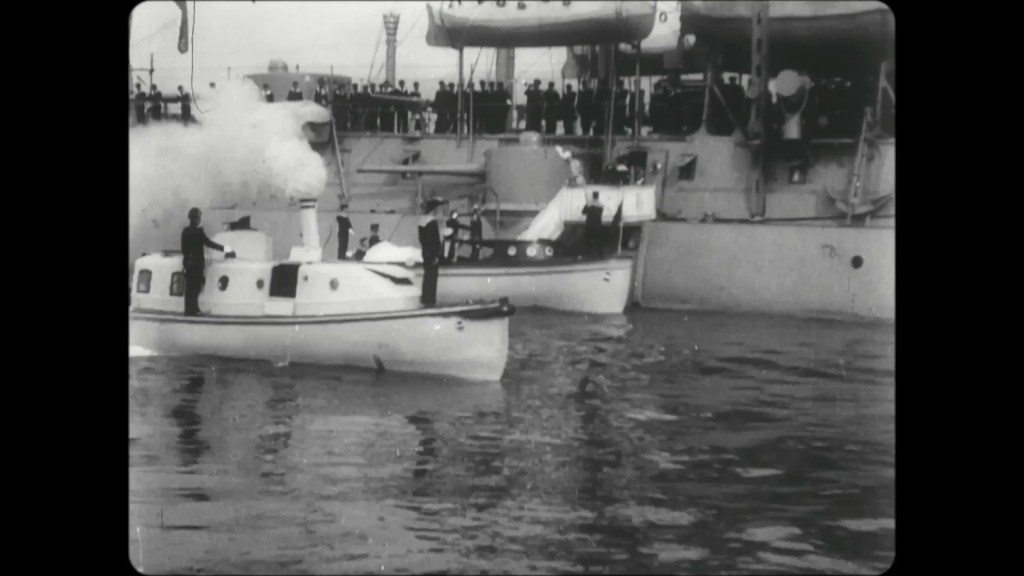

[Ankuft des Fürstin Wilhelm I. zu Wied in Durazza (Albanien) März 1914] (1914; Fr.; Anon.). The delegation from Iran. Crowds of children. Fezzes. Dignitaries in warm coats. Soldiers march, a little out of step. Troops of children in uniform. Fezzes in different tones. The flag of Albania raised for the first time. Smoky seas, naval ships, dignitaries in big hats. Medals. Sashes. A plumed hat rubs against the underside of the deck’s awning, so the prince must stoop. Awkward salutes, handshakes. Tiny little steamboats gleaming white next to enormous cruisers. Parades of flag-bearers. An old man sweeps muck from the red carpet. The film ends. (There’s a small theme in early cinema actualities that should be written about: the people seen on screen who clean up after the people we’re supposed to be concentrating on. They’re always at the edge of the frame, or enter after the main event has passed. The film catches them from the side, or turns away just as they enter the frame. Here, the film ends just as they are beginning their work. But there they are, or were, toiling away in the margins of history.)

Eine Frau von Format (1928; Ger.; Fritz Wendhausen).

A German film with French titles. “Somewhere in Europe”, we find the realm of Sillistria. A charming way to illustrate the film’s fictional location: a hand draws a map with a brush. We see Sillistria, sandwiched between two other fictional kingdoms, Thuringia and Illyria.

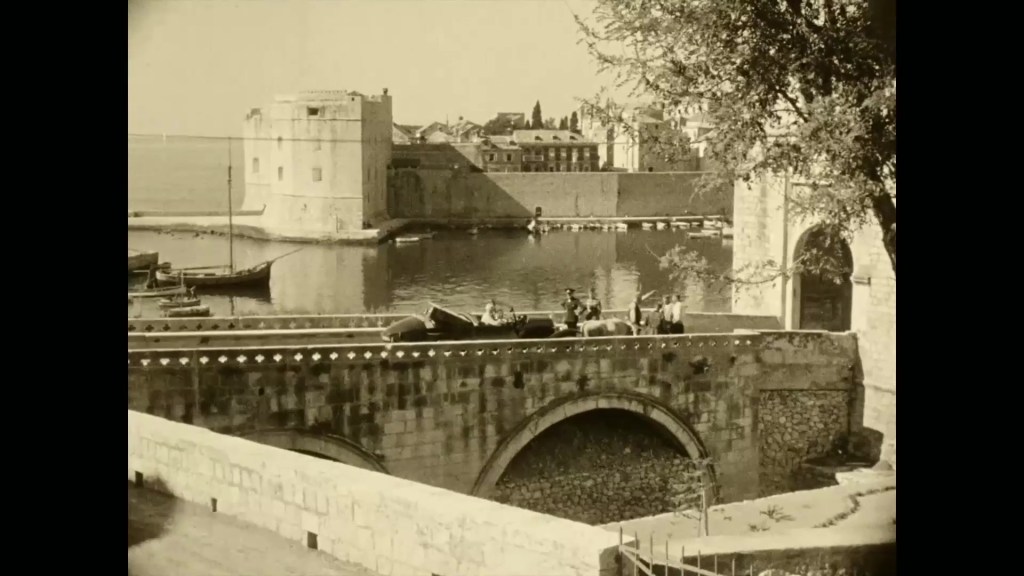

A gorgeous shot of an obscure city on the coast. (The real city of Dubrovnik must remain nameless.) Sillistria’s “fleet” consists of three small boats, the “army” of a handful of men and a cannon. The residence is a lovely villa. The Chancellor (Emil Heyse) arrives in splendid uniform. The local women in “traditional” costume, a kind of blend of east and south European, vaguely Balkan, vaguely Slavic, vaguely Turkish.

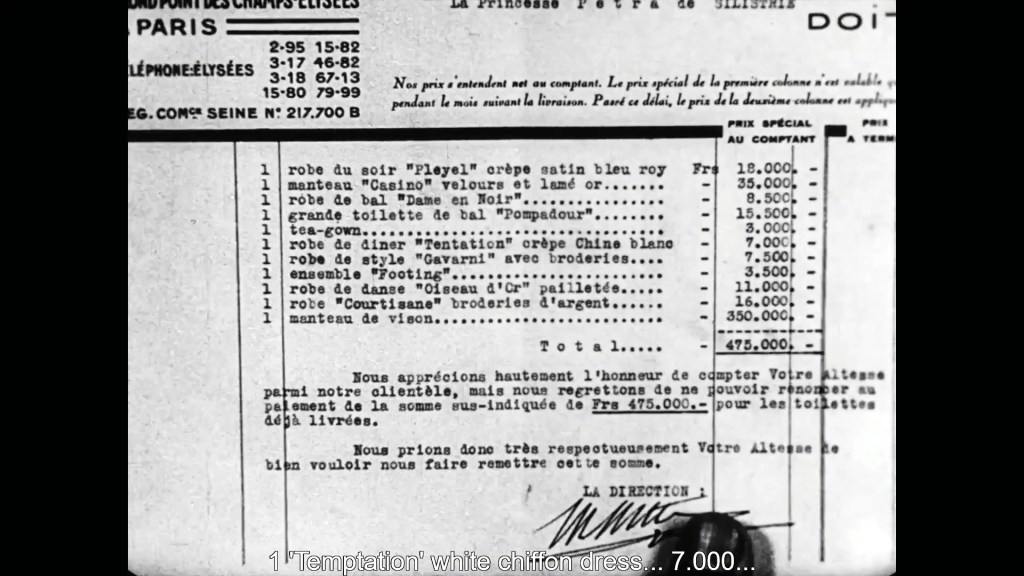

Princess Petra (Diana Karenne): a lovely close-up revealed when she lowers her fan. She is cool, languid. Eyes that move expressively, assuredly. She smokes. A modern Princess for an ancient kingdom. We are told about Thuringia and Illyria, to which the Princess is determined to sell an island, Petrasia. The Chancellor threatens to resign. “You want me to have to walk around naked?” she asks, a twinkle in her eye. She shows him her bills. The Chancellor kisses her hand, shrugs, laughs.

Count Geza (Peter Leska) from the kingdom of Illyria. The attendant (Hans Thimig) is full of sly winks.

Now we are introduced to Dschilly Zileh Bey, special envoy of Turkisia (Mady Christians), broken down on the road into the city. Gorgeous scenery, a map (this time professionally printed) of the fake kingdoms. How to find her way around here? She offers money to a local, who tows her car with his bull.

In the court of Sillistria, Count Geza flirts with the Princess. The arrival of Dschilly causes chuckles and consternation. Elegant tracking and lift shots of her entry into the hotel. And a panning shot of her disappointed glance round the paltry room. The “bathroom” is simply a portable metal tub. Dschilly looks the most modern of all the characters: her smoking, her fashionable beret, her elegant yet simple dresses and shawl. And the modernity of her knowingness, her visible intelligence. Here’s a woman who knows what she wants and will find a way to get it. Charming, yes, but direct too.

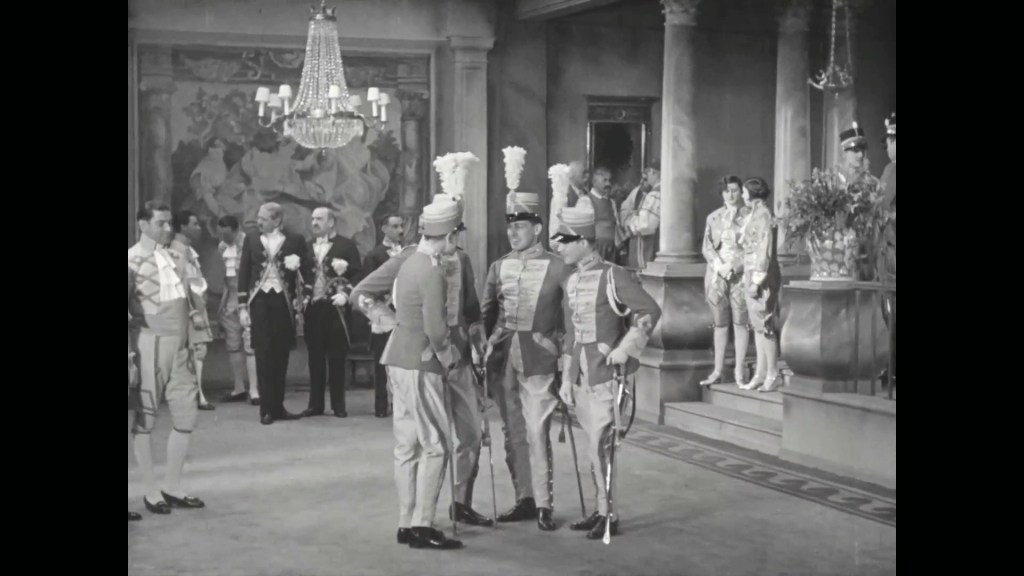

Her arrival at the court. She and the Chancellor exchange mutually curious looks. (Then again, Christians always has a half-suppressed smile.) Smiles and great curtesy to her “rival”, Count Geza.

That night a soiree (tinted a lovely rose). The comic adjutant is here again, grinning and flirting and taking a sneaky drink as he serves the ambassadors. Geza and Dschilly are dancing, the camera following their movements on the dancefloor. Thence to the gardens, a quick kiss on the hand. But Dschilly wants the island. Geza wants to advance his career. The stakes are set out. (On his way out, Geza plays a sly trick: he tells the concierge that Dschilly does not wish to be woken.)

So the Princess is left waiting, and all doubt Dschilly’s qualities as an ambassador. Only Geza turns up, and begins smarming with the Princess. Attended by female servants in page attire (very charming, very ’20s), they prepare to set off together. Dschilly wakes and is angry at the trick, but soon that familiar smile breaks out: she has a plan. She demands to speak to Her Highness.

After a trip on the little yacht, Geza gets the Princess alone on the island of Petrosia. But the giggling adjutant is in the background, so too the Chancellor. Dschilly waits at the little quay, but she makes friends with the gossipy attendant and he spills information on the Count’s planned assignation that night. She and the Chancellor then row around the island, Dschilly doing the rowing. She assures him that tonight Count Geza has his reception. The conversation brings them around the island within sight of the Princess and Count. Dschilly leaps into the water to feign drowning. The Count rescues her and gets her ashore. He insists on rowing her back to the mainland. Dschilly sits up, soaking wet and ever so charming. She flirtatiously says that this is her response to his own scam that morning.

That night, the Count prepares for his lady. The door rings. The attendant answers, only for a huge supply of food and drink from the court to arrive for the count’s official reception. The attendant keeps having to answer the door as more and more people arrive, guests for the full-blown diplomatic reception that Dschilly has mischievously pulled forward by a day. Soon, dozens of high-ranking guests are swarming into the Count’s residence. The next moment, the crowd is upon him—and he had dismissed all his servants for the night. So Dschilly organizes a team of officers to serve the drinks. Meanwhile, the Count orders his attendant to remove all the candles. But he is spotted by Dschilly, who suspects another scheme. The Count is wrestling with a fuse box. The lights go out and, after a meaningful exchange between Geza and Dschilly, the guests are forced to leave.

At last, the Count’s guest approaches: it is the Princess. But the attendant who serves them is… Dschilly, delightfully made up and dressed as the real thing. She can barely contain her smirk as she serves, “accidentally” catches his hand with a match, and frustrates his flirtatious dinner. The Princess leaves and the two rivals are left together. Outside, a group of officers with music and gypsy dancers arrive. One of them soon finds the Princess’s shawl, but it is Dschilly who takes it away with her. Before she leaves, Geza confesses that he loves her. Dschilly smiles in rapture but then accuses him of saying the same thing to the Princess. She says she will be his wife—if he gets her the sale of the island.

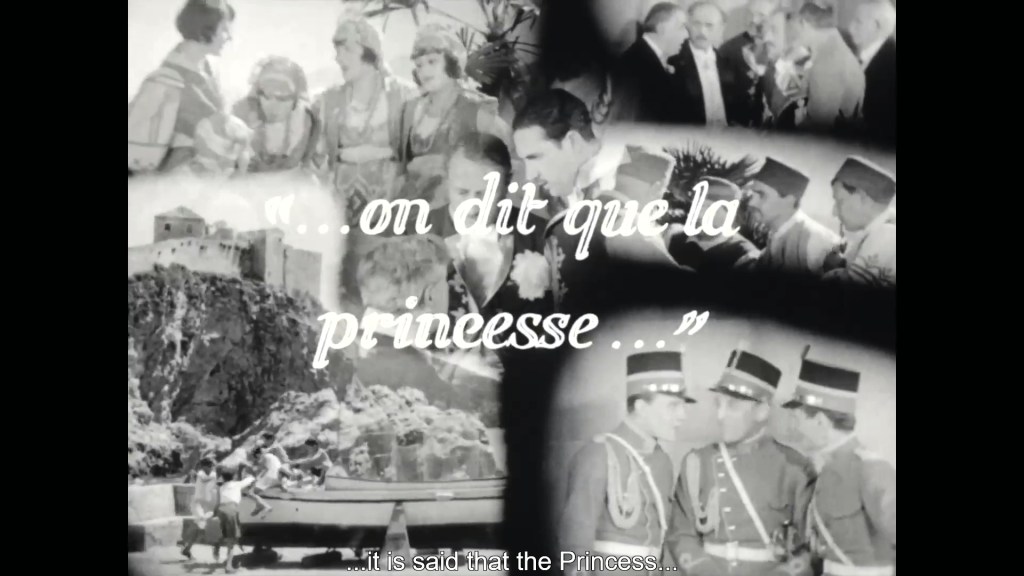

But rumours are flying—via superimposed text and split-screen—about the Princess and the Count. The Princess demands the truth from the attendant, who admits that Dschilly was also at the Count’s residence. Angry, the Princess decades to withdraw the sale of the island.

The official hearing of the ambassadors’ withdrawal. The Princess enters in her regal finery. But as she prepares to strip them of their positions, Dschilly unravels the Princess’s shawl from her sleeve. Consternation… until Dschilly says she gladly accepts the gift that had already been given to her by the Princess. It’s her trump card: the Princess sells the island to Turkisia, “so ably represented” by Dschilly. But in private Dschilly gives the contract to Geza, announcing to the Princess that they are soon to be married—and that she will be giving up her career as ambassador. We see the happy couple, with the grinning attendant in the back seat, driving away. Naturally, it is Dschilly who sits at the wheel. Fin.

Day 6: Summary

I wrote last year that The Runaway Princess was meagre fare. Eine Frau von Format is hardly more substantial in terms of plot, characterization, or emotional depth. In all these respects it is simple and superficial. But it has the advantage of both budget and location over Asquith’s film. It looks prettier, has more to display and displays it more lavishly. Costumes, sets, and glimpses of the real Balkan exteriors are a tremendous advantage. So too the fact that the expanded cast gives more of a chance for more performances to bounce off each other. Mady Christians is always watchable, always charming, always doing something: a sly smile, a flash of the eyes, a sudden movement that implies thought and cunning—even emotion. She gets to play alongside Emil Heyse and Peter Laska and Diana Karenne—and clearly has a fine time doing so. The cast is uniformly excellent, full of precise and meaningful characterization. (Even a minor figure like the hotel manager, played by Robert Garrison, gets several little comic turns.) The direction is clear, the photography is lovely, and the tinted print looks gorgeous. (The piano accompaniment by Elaine Loebenstein is also very good.)

But the film is all surface. Eine Frau von Format is charming but not moving. And it’s funny but not biting or satirical or meaningful. Wendhausen’s direction is skilled without enhancing or adding to the story. There are a few nice tracking shots, but they are more used to reframe the action or move from long- to medium-shots. Little meaning is added by any of them. Wendhausen tells the story with perfect skill, but nothing more. He was no Lubitsch, nor was he a Stroheim. This Ruritania has none of the sheer fun or sophistication of Lubitsch’s fantasy kingdoms, nor any of the emotional depth or satirical bite of Stroheim’s.

But is it fair compare such a film to the greatest examples of the genre? Am I undervaluing the film? I should say that Eine Frau von Format is certainly about female agency, about how a woman can use intelligence and wit to negotiate power structures and achieve her goals. Mady Christians is superbly clever, and managing her performance to be so charming and sophisticated while also showing such cunning is wonderful. But there are no great depths to her character. She softens just once, reveals some sense of her inner life just once: when Geza confesses his love for her. Her charm melts away and she looks vulnerable for an instant, then smiles in a way that reveals inner joy. It’s a great moment, but fleeting. Soon the charm resumes, and the film has no means to explore—no interest in revealing—the inner depths that might lurk inside its characters. So, yes, I did enjoy Eine Frau von Format—up to a point. It’s a first-rate second-rate film.

Paul Cuff