Day 5 brings us both closer to home (well, my home) and further afield than we’ve been so far. Closer to home because today’s programme consists of nineteen British films preserved in the collection of the Filmoteca di Catalunya. Further afield, because these are the oldest films being streamed from Pordenone this year: we begin in 1897 and go so far as 1909. And further afield in another sense, since many of the films recorded events happening far beyond British shores. So, as well as visiting the south coast and Surrey, we go to the north of England and Scotland, but also to Spain and Sri Lanka…

Brighton Seagoing Electric Car (1897; UK; George Albert Smith). Waves breaks amid a downpour of cellulose scratches. Our eyes adjust to the past. Foaming surf, grey seas. The blank sky of a century-and-a-quarter ago. And we behold the strange, dark form of the “electric car”: an open bus of sightseers, moving slowly above the water. The population of the past, specks of faces, waving arms. The past looks back at us, beyond us, to the land behind the camera.

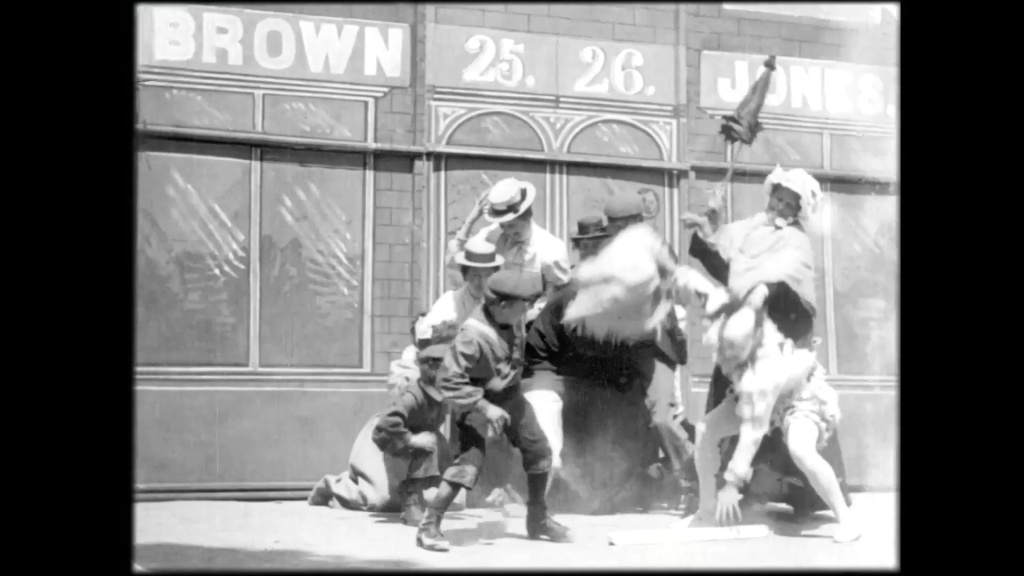

The Inexhaustible Cab (1899; UK; George Albert Smith). A capering clown, a carriage, a canvas street front. The clown ushers his passengers—Victorians all—into the cab. More and more step in. Men, women, boys, girls. The clown joshes with a woman, shoves her in, chucks a child on the roof. The carriage disappears. The occupants are left in a pile. The old woman beats the clown with her umbrella.

Dalmeny to Dunfermline, Scotland via the Firth of Forth Bridge (1899; UK; Warwick Trading Co.). The past is slow. The frames crackle with debris. Frames disappear (we plunge into the dark). People stand by, watching us. The camera is mounted at the front, we see the tracks move under us. We pause to let a train pass in the other direction. (Who is behind those windows? The glass is dark, the interior invisible. The past keeps its secrets.) The Firth of Forth Bridge, long, long ago. The beams and girders close in on us. Time skips. We move through a small, uninhabited station, into a cloud of steam and smoke. (It’s a beautiful moment, a haunting transition—for we never know with such a film when it might end, where we might emerge.) Into a tunnel, through it. Gleaming coast. A bleached sky. (The tinting clings to the trees, the shadows of the rails, the side of the walls.) Fields and trees. The silhouette of a town suddenly appears. (And I do mean suddenly: it’s like the exposure suddenly recovers, as when your eyes adjust after walking from bright sunlight into a dark room.) Where are the people here? Here are two: two workmen on the track in the tunnel. They are just silhouettes, shadows. We cannot see their faces. Do they see us? They move aside and let us pass. We approach the station. Two figures await us in the light. But the light eats them up. The film dissolves their faces in the glare of ancient sunlight. The lens is about to bring them into focus when the film stops.

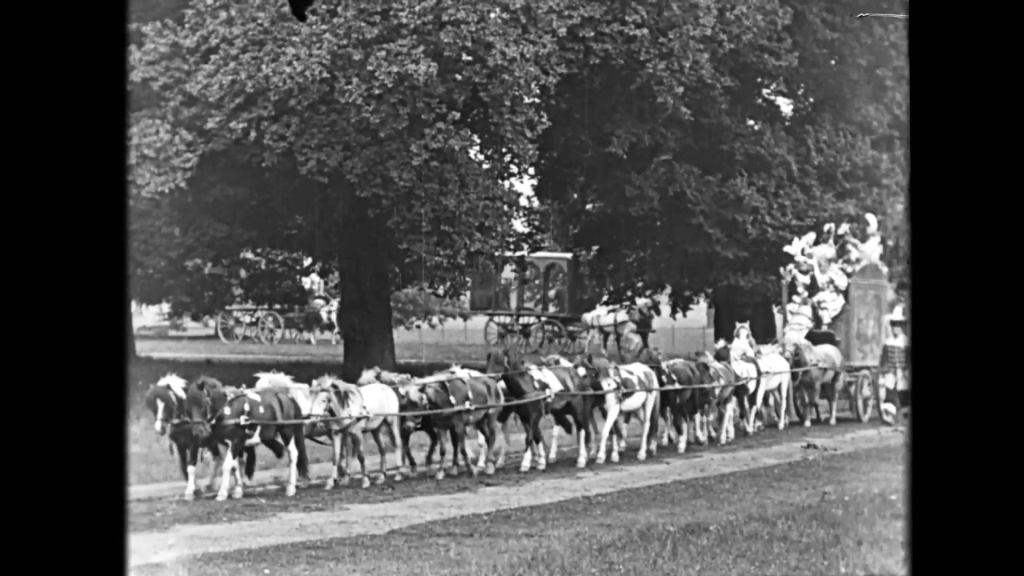

Review of Lord George Sanger’s Circus by the Queen (1899; UK; Warwick Trading Co.). Twenty horses pull a carriage loaded with performers. Another dozen horses draw the next, surmounted by a band. Huge flags. Camels. Two horses pull an even larger brass band. (The horses struggle under the sheer weight, slipping on the muddy road, their awful effort captured forever.) Ever larger carriages, more absurdly decorated. A black man stands atop a horse. A flotilla of boats (their carriage wheels and horse legs peeping from below their painted skirts). Fake beards. A moving forest of trees. “Lord George Sanger” (the biggest flag yet). Elephants, ridden by non-white performers. No-one is watching them but us. The dark, distant trees stand still.

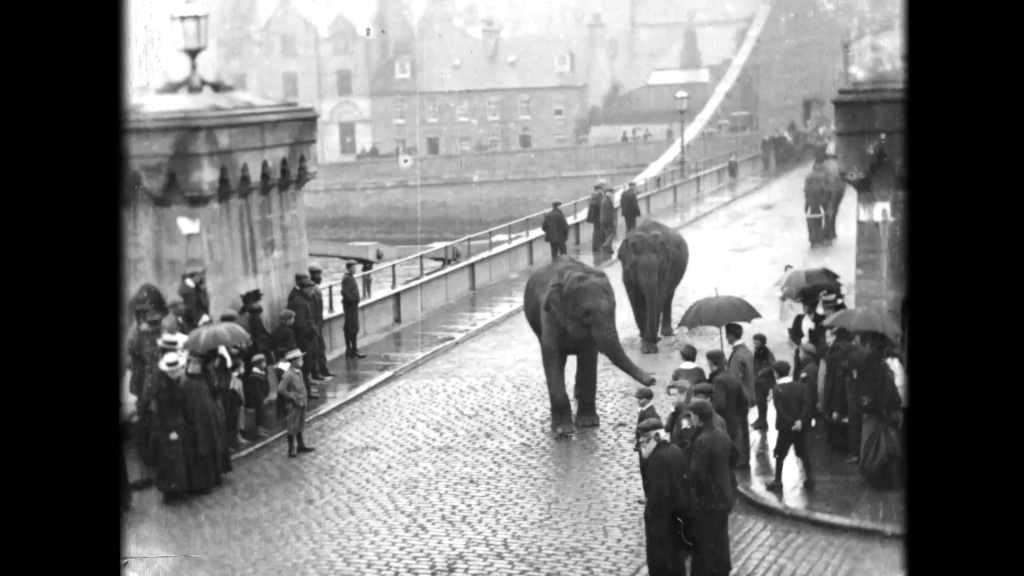

Sanger Circus Passing though Inverness (1899; UK; John McKenzie[?]). The circus again, now riding past spectators. Unattended elephants scamper along the cobblestones. Unattended camels hurry past a gaggle of unattended children. Flat caps. Umbrellas. The cobbles gleam with rain.

The “Poly” Paper Chase (1900; UK; Warwick Trading Co.). A man trailing shredded paper hurtles past. Through a muddy field, more runners pass, slipping and sliding. Long shorts, long sleeves. Edwardian sportsmen. Moustaches. Determination. A series of streams, muddy expanses. The men leap into water made to feel all the colder by the overexposed celluloid. The trees are bare. The film frame itself seems to shiver.

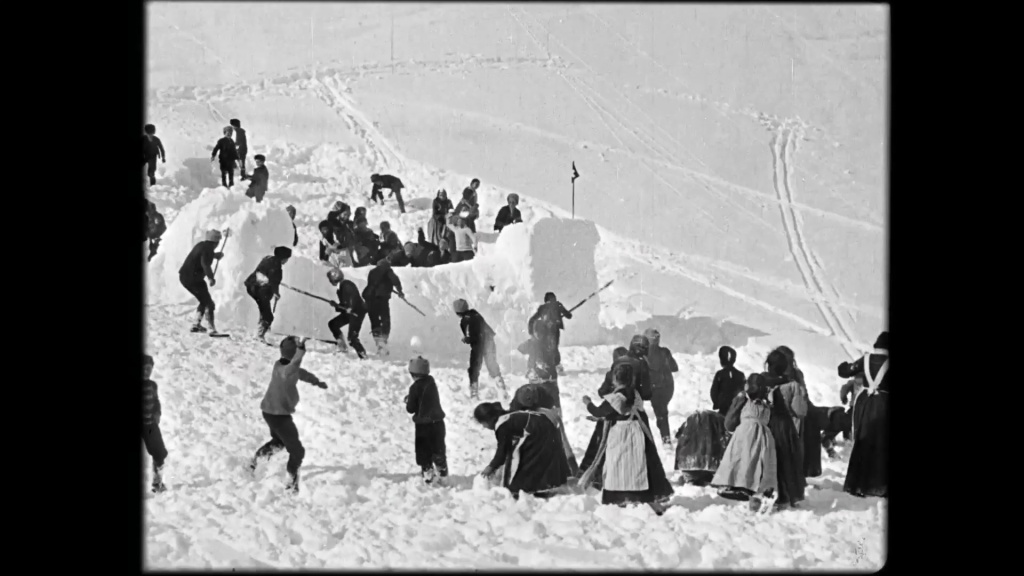

The Wintry Alps (1903; UK; Frank Ormiston-Smith). So, to winter. A snow fight. A fort made of snow. The camera is impassive. We see sled tracks in the distance, across the slope. The fort is attacked with poles. The crowd in the foreground consists mostly of girls and women, but the sticks and poles are wielded by boys and men. The film cuts closer. A chaos of snowballs. A girl glances behind her, towards us. The scene ends. A children’s ski race. Young faces tense with concentration, or with breathless smiles. The troupe move past us. We see them again, then lose them forever. A slope. Adult skiers. Someone falls. A new view: a ski ramp. Skiers jump. We see them take off here, and land in another shot taken further down the slope. A crowd looks on. Another slope. Skiers sliding and falling. It is pleasingly amateur, imperfect, eager. Very few keep upright down the steep gradient. A final figure lies in the snow. Just before he stands, the film ends.

An Affair of Honour (1904; UK; James Williamson.). Two men overlook a windswept patch of sea. Top hats, moustaches, goatees. A fight, a thrown drink. An exchange of cards. A change of scene: now, distant chalky hills. A treeless valley. The two men, the two seconds. Clumsy disrobing, clumsy practising. How will this end? Shots fired. The second shot in the foot. Another round. A witness is gunned down. Another round. The doctor is killed. Another round. The other second is killed. The only other witness runs away. The two duellers observe the field strewn with dead. They shake hands. (The film presages a marvellous film by Max Linder from 1912: Entente Cordiale, in which two nervous duellists fire multiple shots and kill all the witnesses, as well as birds in the sky and trees. They are so overjoyed to be alive that they run off ecstatically together.)

Perzina’s Troupe of Educated Monkeys (1904; UK; Charles Urban Trading Co.). A table filled with monkeys in clothes. A man in a Panama hat and linen suit oversees them. He sports a sinister moustache and pince-nez glasses. The camera pans up and down the hairy ranks. We see a monkey made to do a solo. It looks anxiously over its shoulder. The film ends.

Elephants Bathing in Ceylon River (1904; UK; Harold Mease). Elephants and locals in the river. The locals sit atop the elephants. One of them is rubbing down an elephant’s brow, scratching behind its ear. The elephant lies on its side in the water. The Sri Lankan waters gleam with a warm yellowish tint.

[Drill of the Reedham Orphans] (c.1904-1912; UK; Urban Trading Co.). A square. An audience. Women with floor-length skirts. Big hats. The children perform gymnastic routines in dark trousers and white shirts. An adult in uniform looks on from close by. He stands at the centre of their manoeuvres. They form a cross, a star, stand on one another’s shoulders, file past, form a moving circle and counter-spinning spokes.

Venice and the Grand Canal (1901?/1904?; UK; Urban Trading Co.). The camera floats towards the Rialto bridge. In front of us, a boat loaded with barrels. A few passersby stop look down at us. A boat passes in the other direction. Gondoliers silhouetted against the bright waters, the overexposed sky. The camera draws close to another boat. A man is sitting, looking at us. Just as we are about to glimpse his face, he gets up. The film ends.

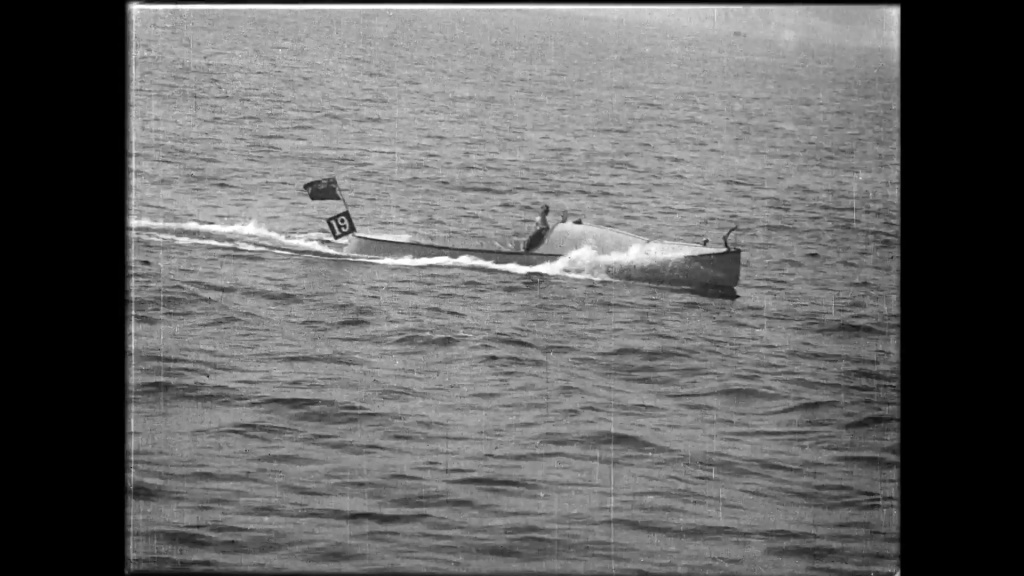

Edge’s Motor Boat. The Napier Minor (1904; UK; Urban Trading Co.). Monochrome waters. A sleek white boat, bearing the number 19 and the British flag. Another boat cuts through the waves. The edges of the frame ripple with wear-and-tear, like a watermark of time.

Fixing the Swing (1904; UK; Alf Collins). A family: the woman washing, the man snoozing with his face under a handkerchief. The girls wake him. He shouts angrily. They want him to make them a swing. They pass him rope and seat. He starts hammering moodily into a wooden overhang. (Just on the edge of the frame, in the background, a man watches the scene unfold.) The woman makes encouraging faces. The children dance in anticipation. The swing is made. The father shows its strength by sitting on it. It collapses, wrenching off the wooden beam above: water cascade over the family.

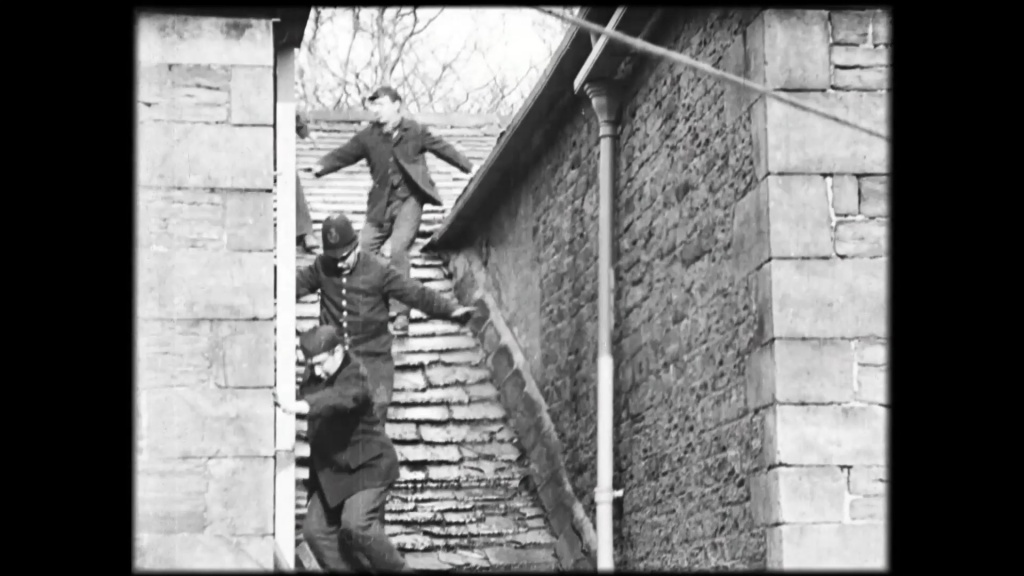

Eccentric Burglary (1905; UK; Frank Mottershow). The title bodes well. Two burglars, tumbling over a wall. They try the shutters of the house. They try clambering on each other’s back. Then the film helps them: the footage is reversed, and we see the burglars miraculously leap up to the first storey window and enter. Two policemen approach. The film aids them also and they slide up the ladder. A chase ensues over the rooftop. The camera miraculously looks down at the wall (or its recreation). Men climb up towards us. Locals stop in the background to watch the action unfold, smiling, as the performers now miraculously ride in reverse backwards up a hill with horse and cart. The horse vanishes between frames. The burglars flee, now tumbling backwards up a hill. The police slide up a banister, leap backwards over a gate, over a tree. But nothing can beat a good old-fashioned truncheon. A quick knock on the head and the film ends.

Her Morning Dip (1906; UK; Alf Collins). A well-dressed woman, white dress, hat, and veil, attracts two eager men. (A crowd gathers in the background to watch the film being made. They do not interfere with the action, even as it turns into a car chase.) We end up on the coast, at the seafront. Real life goes on all around us, and our eyes are drawn at least as much to the surroundings as to the two cars that now pull up in the foreground. (Coachloads of day-trippers. A girl and boy walking together, the boy eagerly pointing ahead.) Several more men are now following the woman, a comically leering mob desperate to catch a glimpse of her ankles. She goes into a bathing tent and the mob clamber all over it. The tent flaps eventually part, and from it walks an old bald man in bathing costume. Followed now by a huge crowd of smiling onlookers, he camply tests the waters and hops like a kangaroo into the waves, pursued by laughing children.

The Royal Spanish Wedding (series): Automobile Fête before King Alfonso and Princess Ena (1906; UK; Félix Mesguich). A southern sun. A motorcade of people in hats, the vehicles decked out in flags and umbrellas. The other vehicles covered in flowers. One car is halted and reprimanded. Another breaks down. Men and women stand to gesture—to us? to an unseen crowd? Great clouds of exhaust fumes rise into the hot sky. A brass band plays as the fleet of cars stands and watches others pass by. Women in huge hats and veils hold umbrellas up to offset the heat. A driver is handed a glass of water. From a balcony, the royal couple stand and watch.

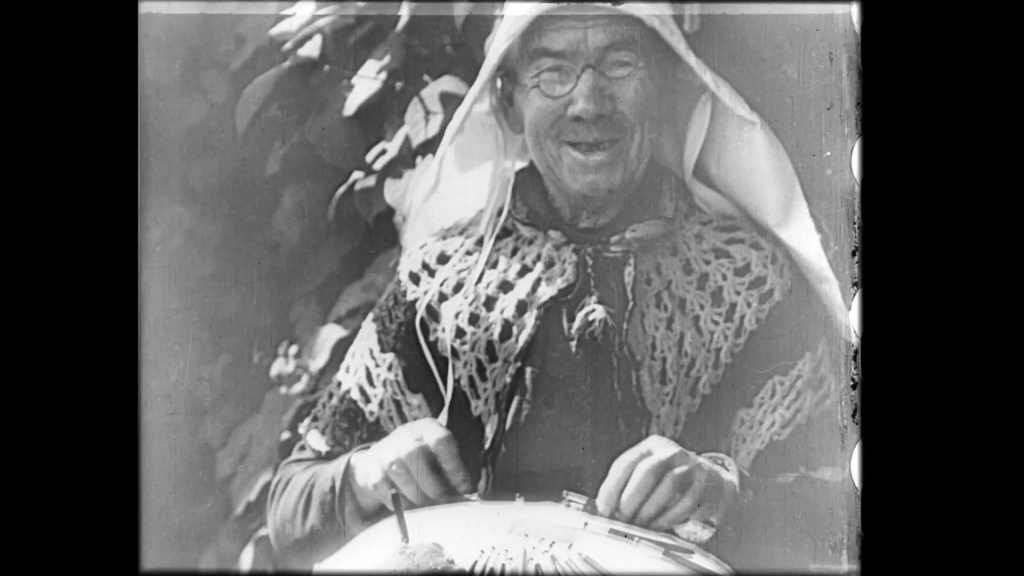

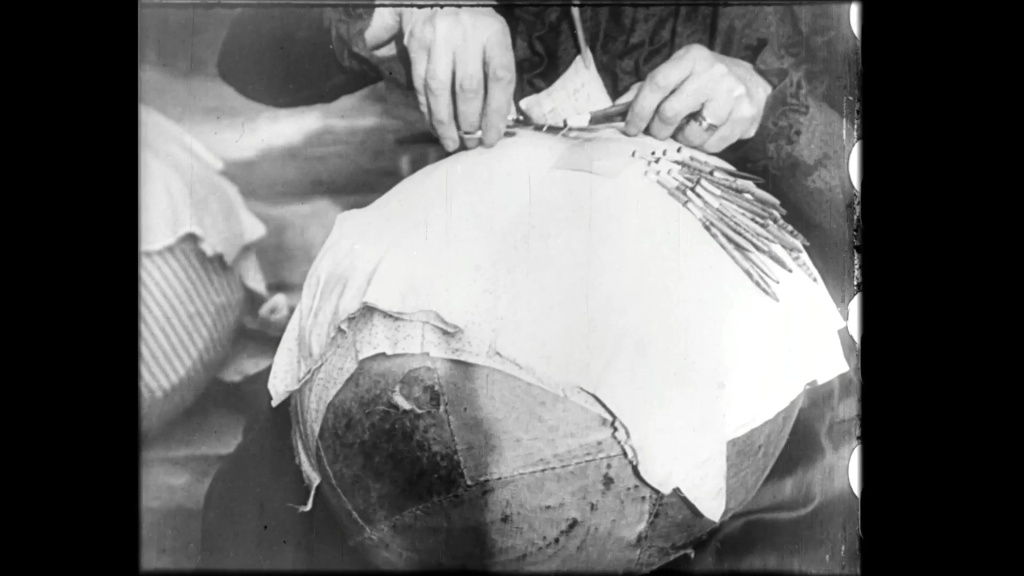

Lace Making (1908; UK; Cecil Hepworth). Outside a small house, women are at work. Their hands move with impossible speed over the lace. (A cat walks up to a woman, its tale raised in greeting, and rubs by a skirt.) The oldest woman makes uncertain eye contact with the camera, then immediately looks down. We see other women’s faces. A woman with lopsided glasses holds our attention. She’s talking to us, smiling and jokes. The camera holds on her for a long time. It’s immensely moving, this immediacy of the past, and these lips speaking to us in silence. It is the suspended life of the past. Another shot of the leather ball over which the lace is made. In this close-up, the cameraman’s shadow falls into frame. Just as we watch the woman’s hand make the lace, we see the cameraman’s hand crank the camera. It’s a spellbinding detail. Just as we admire the amazing lacework in close-up at the end, so we admire the work of the camera. In a final shot, the group of older women walk towards us. Just as the woman with glasses is about to reach us, the film ends.

The Robber’s Ruse, or Foiled by Fido (1909; UK; A.E. Coleby). Mother and daughter, a well-appointed room. The mother leaves, under the eyes of a suspicious older woman outside. (At one side of the frame, a dog observes the scene.) The child, home alone, answers the door to the apparently fainting old woman. She helpfully offers her a glass of spirits, but then the intruder disrobes to reveal himself as a man. Through a keyhole, the child observes him begin his nefarious work. The child escapes into the garden but is caught and brought back and tied up. The dog barks, breaks free, runs—summons a policeman. (Front the little gardens of the terraced houses, women stand by and watch the filming take place.) The burglar is foiled, the dog joining in with the policemen in wrestling the man to the ground. Mother, daughter, and dog are eventually reunited before the camera. The child grins delightfully right at us, as happy to have her mother and doll and dog today as she was in 1909.

Day 5: Summary

What an absolutely delightful programme. I wrote on Day 2 of the delight in seeing the background world of Wilhelmine Germany in Harry Piel’s films, and here we have a much wider and more deliberate looks into the world as it was at the dawn of the twentieth century. The “actualities” are especially wonderful. Dalmeny to Dunfermline is an utterly captivating film. I love early cinematic documents like this, where the camera glides through the past. (And yes, it helps that I love travelling on public transport and sitting gazing out of the window. It’s an exquisite pleasure over any distance of travel.) The deserted streets are haunting and beautiful, the glimpses of faces who look in surprise or suspicion at us, the sense of never quite knowing what’s coming next. Even the glitches in continuity, the nibbling of decay at the frame—all these things convey the past and the passage of time, and our place in history too. Then there are the utterly unexpected moments of surprise for us. In Sanger Circus Passing though Inverness, there is a moment when one of the elephants trotting unattended along the street turns to its left toward the little crowd watching it go by. The animal reaches out with its trunk towards one of the children. I found this little gesture, lost long ago and recaptured here, absolutely heartbreaking. It’s a gesture of curiosity, of fellow feeling, of one creature reaching out to another. It’s beautiful and sad, and it invites other questions from our own vantage point in time. What was the fate of the elephant? Where was it born? Where did it die? Were elephants buried? And what became of the child? He must have come of age during the Great War—did he survive? Did he remember the elephant that reached out to him that day in 1899?

The “fiction” films are just as capable of delight, but a kind of delight rooted in the haphazard, on-the-fly method of filming. In all the films—fiction or not—there are bystanders who look with bemused curiosity at the actors performing or the film crew filming. Real life c.1900 is everywhere in a way that intrudes delightfully on any pretence of fiction. The performers themselves are part of the life and time we see on screen; it’s just that they’ve stepped out of the crowd for a moment to do a turn. Then the cameras will stop, and they’ll step back into the crowd, into the life that the bystanders are living, into the time and culture that they share with everyone on screen. I’m sure I could go on about these films—and many other such early productions—forever, for they captivate and intrigue in a way that many later fiction films cannot. So, what a privilege to watch them, with a lovely and sensitive piano accompaniment by John Sweeney. Another great day at Pordenone—from afar.

Paul Cuff