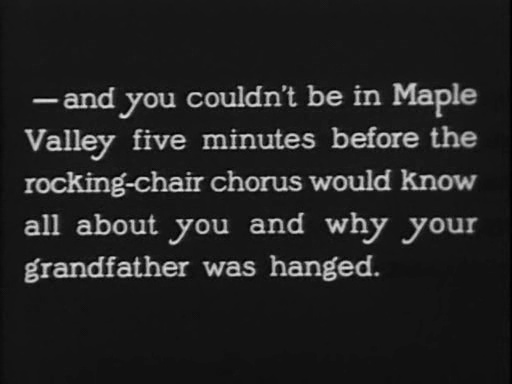

Don’t make this film! That was the advice of exhibitors, producers, and advertisers to Douglas Fairbanks when he mooted the idea of making a costume picture. He asked around his friends and peers, figures in the studios, and even commissioned a survey to get a wider sense of popular opinion. Everyone said no. “Having made sure I was wrong,” Fairbanks later wrote, “I went ahead” (qtd in Goessel, The First King of Hollywood, 257). The film was an adaptation of Alexandre Dumas’s Les Trois Mousquetaires (1844), and Fairbanks pulled out all the stops to ensure his production matched the scale and sweep of the original tale. Lavish sets, big crowds, gorgeous costumes, plentiful stunts… The total production costs were almost $750,000—a staggering sum for 1921. But the film was a huge success and reeled in $1,300,000 to Fairbanks’s company, as well as large profits to United Artists and any number of exhibitors who had booked the film. The success of the film encouraged Fairbanks to make even bigger costume films. The decade saw him embark on the huge productions like Robin Hood (1922) and The Thief of Bagdad (1924), films which dwarf even the scale of The Three Musketeers. So how does the latter rank alongside Fairbanks’s other swashbuckling films of these years?

Rather well, I think—but with some reservations. The film was directed by Fred Niblo, and in visual terms it feels rather safe and stolid. Fairbanks spends the film leaping, dancing, skipping, and hurling himself about the sets. But the camera barely moves, barely even dares offer anything in the way of dynamic editing. It’s as though Niblo is afraid of losing sight of the bigness of the sets, or of any kind of visual movement detracting from the movement of the performers.

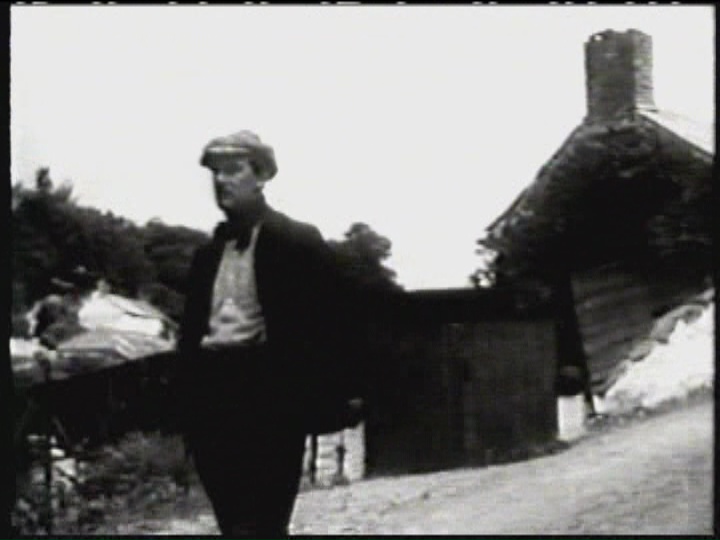

Niblo wasn’t known for his imagination, even in his earlier films. Kevin Brownlow writes that “Niblo’s style was usually lifeless”, producing “his usual series of cardboard pictures”—as evidenced in the Fairbanks vehicle The Mark of Zorro (1920) (The Parade’s Gone By…, 414). Only in the interior scenes with the various courtly intriguers—Richelieu, Queen Anne, King Louis—does Niblo offer closer shots, details that develop character or situation. (For example, Richelieu is seen petting cats, and we later get close-ups of his hand pawing/clawing at the arm of his chair, much like a cat plucks at a piece of carpet.) But the photography is strong, and there are some lovely exterior scenes in the countryside. Niblo gives us a good number of vistas down tree-lined roads, and you sense the scale of the journeys—the distances—between D’Artagnan’s home in Gascony, the city of Paris, and the remote ports of France and England.

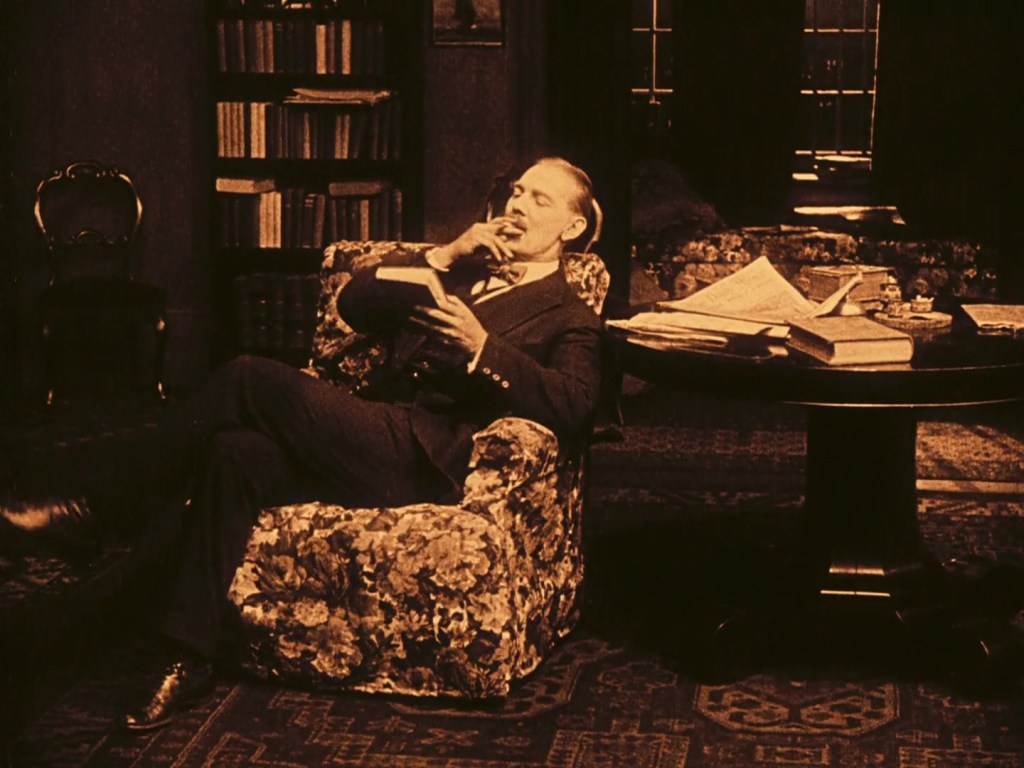

And even if I have reservations about the direction, that’s not why we’re watching The Three Musketeers. It’s Fairbanks who is the life and soul and purpose of this film. I couldn’t wait for him to appear (the opening scenes setting up the intrigue are very stilted and slow). And as soon as he does—sat legs akimbo on the floor, listening to his father’s tales of Paris—I’m grinning as he grins, and marvelling at everything he does. He makes even the simplest actions look balletic, and the most complex feats of strength look simple. He leaps onto and off horses, backwards and forwards; he jumps up walls, climbs over rooftops, jumps from battlements, swings from windows, slides down bannisters—and all with elegance, with style, with joy.

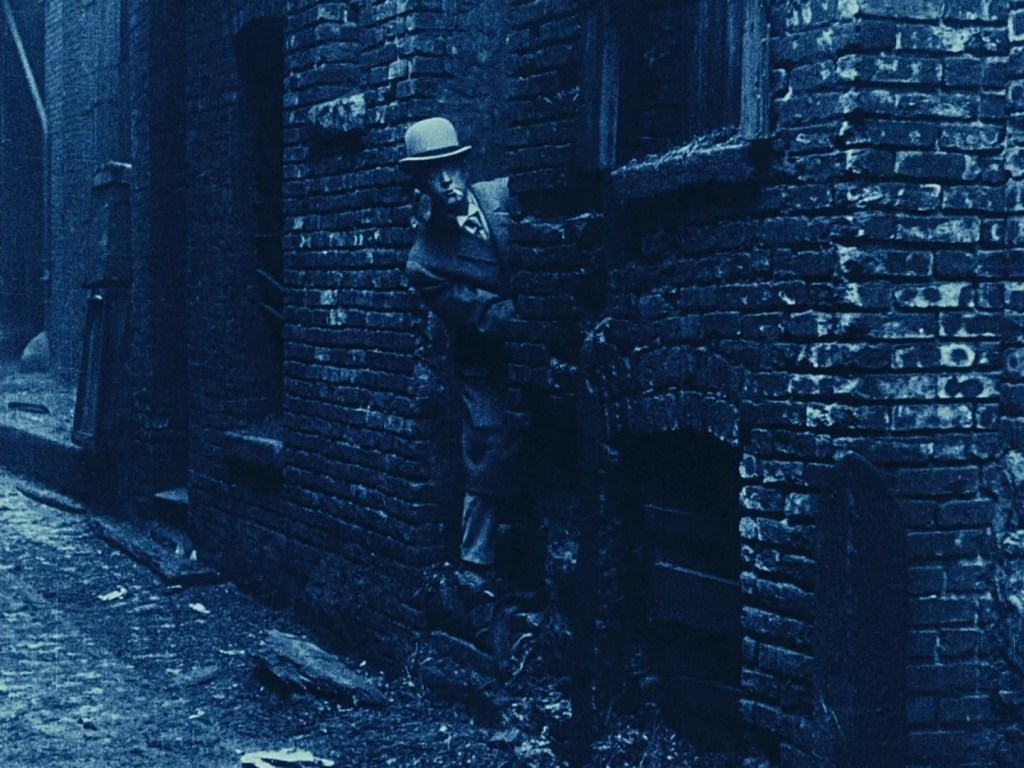

We are told early on that he’s been taught to do everything with pride, to accept no defeat, to fight back at every opportunity. And so he does, crossing swords first with the Cardinal’s guard Rochefort, then with the Musketeers, then (alongside the Musketeers) with the rest of the Cardinal’s men. Look at the way he evades the latter, first by hurling himself around with sword in hand, then by sheer pace. When he runs from a mob of them in once scene, he skips in glee when he knows they can’t catch him. It’s such a lovely detail, and makes us marvel not merely at his physical prowess but the lightness with which he uses it.

I must also mention Fairbanks’s moustache. This was the film that inspired him to grow it, and he kept it for the rest of his life. It gives him a more continental look, but it also makes his face more complex, more interesting. It’s like a punctuation mark or accent for his smile. The film doesn’t offer that many close-ups of him, but there is one gesture that he makes several times in the film. It’s when D’Artagnan senses something is awry, or that he’s scented a clue to the intrigue. He rubs his nose on one side, as if to suggest he’s got a sniff of something interesting. I don’t think it quite works, and it’s an awkward equivalent of something that could be done by or with a close-up. It’s not as subtle a trait as used in The Thief of Bagdad. There, Ahmed (Fairbanks’s character) makes a clasping gesture with his hand to signal desire. The gesture is used to signal his urge to steal purses etc, but then—in a brilliant touch—to signal his desire for the Princess. But Raoul Walsh frames the gesture much more convincingly than Niblo does its equivalent in The Three Musketeers. There’s also a striking visual equivalent for the olfactory sense suggested by the gesture in the earlier film. In The Thief of Bagdad, when Ahmed smells freshly-baked bread, Walsh cuts via a focus pull from Fairbanks to the loaf of bread. It’s like a different sense takes over from the visual until the visual can reassert the reality of the scene to reveal the source of the smell. It’s such a lovely moment, and there isn’t anything as sophisticated or visually inventive in The Three Musketeers.

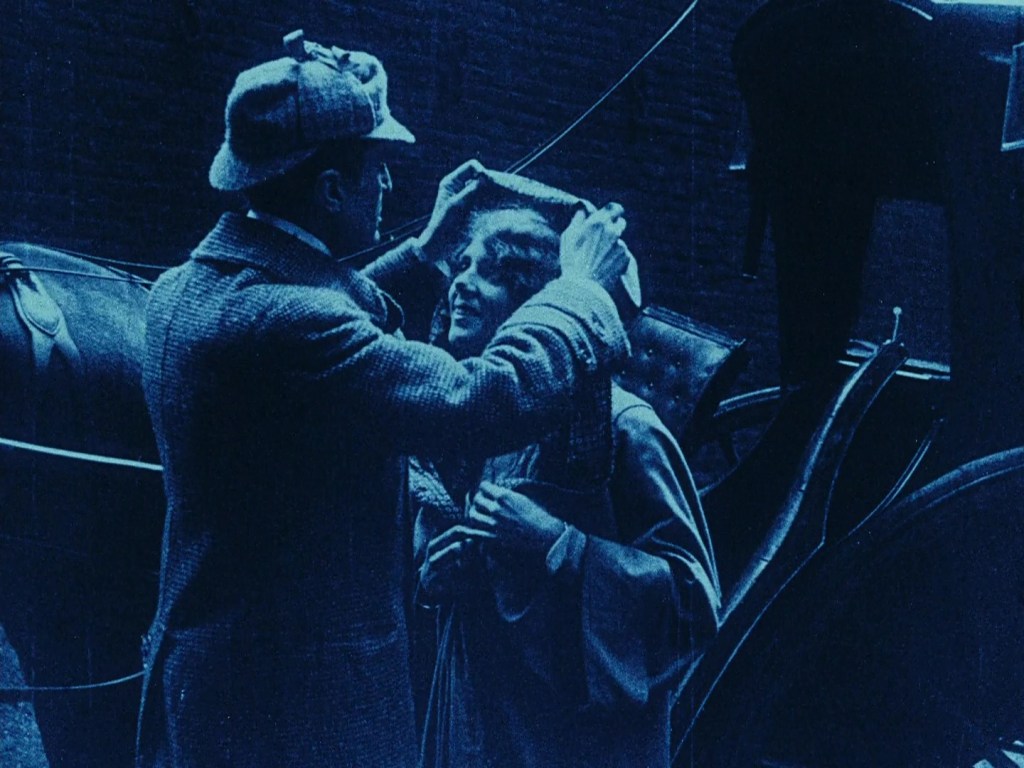

Beyond the more daring tone of The Gaucho (1927), Fairbanks’s on-screen involvement with women tends to be more comic, innocent, and flirtatious than sexual. His romantic gestures—kneeling, spreading wide his arms, pressing hands to heart—are earnest, old-fashioned; even a kiss is a rarity. In The Three Musketeers, D’Artagnan falls for Constance Bonacieux (Marguerite De La Motte). The way it’s done is charming: she drops her ball of thread, and he picks it up. From two different directions across town, they wend their way toward each other, following the thread. But she snips it off, and he loses track of her. Then, when he finds her again, he is looking for lodging. Two neighbouring houses have signs offering accommodation. Constance goes first in to one house, so D’Artagnan bounds up to the door; but then Constance goes into the next one, then back again. What to do? Bold and direct, D’Artagnan simply asks her which house she lives in—and goes in. It’s a lovely sequence, and its tone is comic, the romance having a rather childlike element. Later on, when D’Artagnan chases after Constance in the palace, Captain de Tréville leads him by the ear back to the King: Fairbanks is a naughty child, whose knees we then see tremble as he is presented to King Louis.

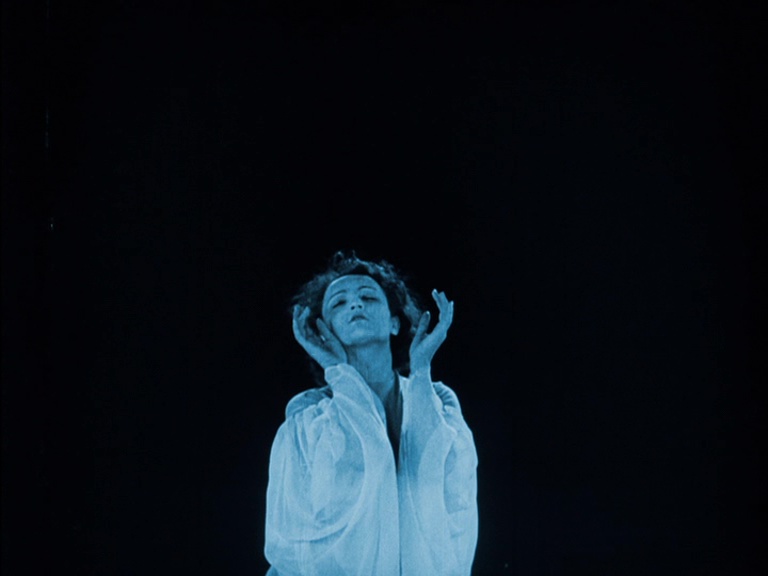

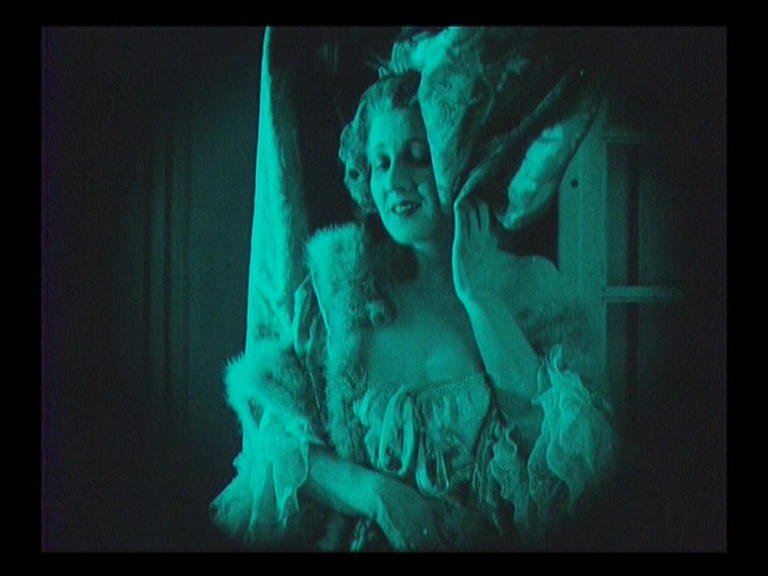

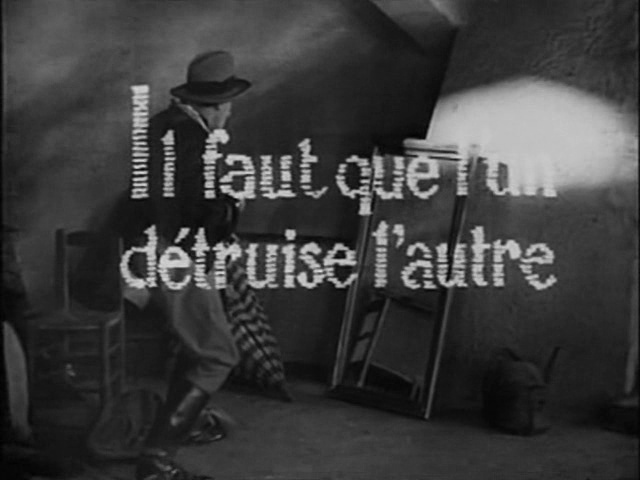

Elsewhere in the film, the sexual politics of the novel are elided or softened. (Care was certainly required to make the source material acceptable to the censors, but you sense that Fairbanks wasn’t interested in romantic melodrama so much as adventure.) Milady de Winter (Barbara La Marr) and D’Artagnan exchange flirtatious glances early in the film, and D’Artagnan will eventually surprise her in bed in order to retrieve the diamond broach she has stolen from the Queen—but (unlike in the novel) they never get involved. Even the affair between the Duke of Buckingham (Thomas Holding) and Queen Anne (Mary MacLaren) is remarkably chaste. King Louis himself (Adolphe Menjou) is jealous of the Queen’s private affair, but his jealousy is not emotionally complex (and hardly inflected with sexual interest).

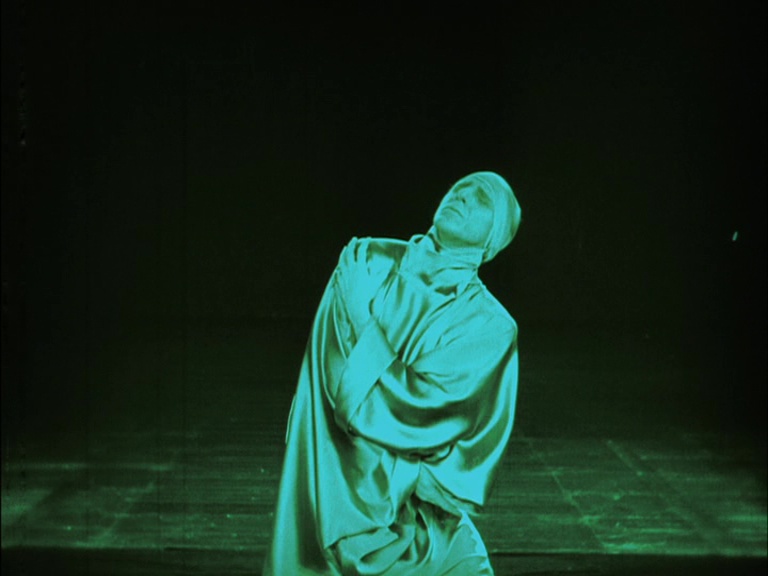

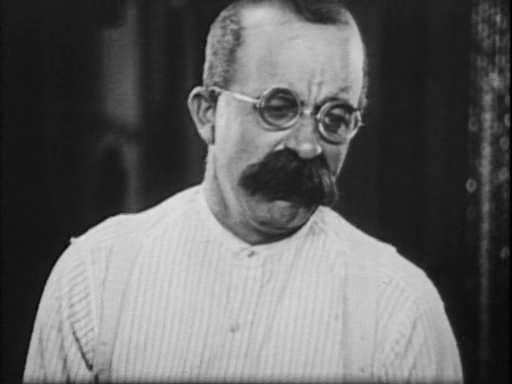

Indeed, the King’s emotional moods—his jealousy, anger, suspicion—are mainly focused on the figure of Cardinal Richelieu (Nigel De Brulier). De Brulier is the most perfect imaginable casting: his gaunt cheeks, long face, distinctive nose, and narrowed eyes. He would reprise this same role alongside Fairbanks’s older D’Artagnan in The Iron Mask (1929), as well as in two sound adaptations of Dumas’s novel. As mentioned before, he is a feline presence on screen. His thin profile, his shoulder-length hair, and his floor-length robes give him a feminine air. Indeed, he spends more time on screen with the King than the King spends with his wife—and he is surely a kind of devilish substitute. There is something almost flirtatious in the way Richelieu needles the King about his Queen. Later in the film, when D’Artagnan flatters Richelieu to delay his scheme to murder him, De Brulier’s performance grows subtly camp. Richelieu suddenly comes over all coy and flirtatious. The handkerchief he has been holding is a signal to his guard to shoot D’Artagnan; but once D’Artagnan begins flattering him, he swiftly withdraws it, and it becomes a kind of girlish accessory. Richelieu is always a magnetic presence on screen. And I can imagine a different director, in a different kind of adaptation, making more of De Brulier than in this film.

D’Artagnan himself enjoys the boys’ club atmosphere of the barracks and the all-male rooms of his friends. Much of the middle of the film is light on plot, instead setting up the relationship between the musketeers. We see how they get by with no money, gambling, borrowing, bluffing. (There’s a nice scene where they successively blag their way into the kitchen of two monks and cadge a free dinner.) It sets up a pattern that would be repeated in Robin Hood, Fairbanks’s next film, where Robin embraces the all-male company of his “merry men”. In that film, Sherwood Forest becomes a giant playground for the antics of Fairbanks and co., who leap gleefully around their idyllic world like ballet dancers. In The Three Musketeers, there isn’t quite the same sense of scale—but the central group of four male friends is the focus of much of the film’s jollity and camaraderie. It’s all very charming, but it lacks emotional depth. Only in The Iron Mask does the friendship of these characters come to mean and feel more: that whole film attains greater weight by being about ageing, and by the sense that there can be no sequel.

The new Blu-ray of The Three Musketeers is by the Film Preservation Society, who also produced the 2021 restoration of the film. Visually, it’s a great treat to look at. The lavishness of the costumes and scale of the sets really comes across. As well as looking sharp and rich and textured, the image benefits from the warm amber tints for the daytime scenes—and subtle blues for the nighttime scenes. Noteworthy in particular is the recreation of the original Handschiegl colour process. When D’Artagnan leaves Gascony, his horse is described as “buttercup yellow”. All the villagers en route and in Paris point and laugh at this extraordinary animal, so much so that when D’Artagnan arrives in Paris he immediately sells the animal to buy a hat. It’s a running gag for several scenes, and one which was visually inexplicable in monochrome restorations of the film. Thankfully, a fragment of a first-generation 35mm print was discovered in 2019 that revealed how the gag was supposed to work: via the Handschiegl process, the horse was quite literally coloured buttercup yellow. The 2021 restoration had digitally recreated the effect, based on the surviving 35mm fragment, and suddenly all these scenes make sense: the film was always designed to have this additional colour element, and all the on-set performances are geared towards this post-production effect.

Finally, I must mention the film’s musical score. It’s a habit among many labels—especially, it seems to me, North American ones like Image and Kino—to describe the soundtracks of their releases in unhelpful terms. As I have written elsewhere, reading in the DVD blurb that the release contains the “original orchestral score” is no guarantee that the soundtrack actually features an orchestra (Cuff, “Silent Cinema”, 287-93). Too often you have to read the small print to discover the truth, e.g. “original orchestral score, arranged for solo piano”. The back of the Blu-ray for The Three Musketeers states that the 2021 restoration is “graced by an orchestral score performed by the Mont Alto Orchestra”. Pause for a moment to consider the word “graced”. Yes, we are indeed more than fortunate to have the “orchestral score”, and it must be an orchestral score because it’s performed by an “orchestra”. Surely! Right? But the small print, in this case the liner notes by Tracey Goessel, make it clear what this actually means:

The Louis F. Gottschalk score, orchestrated for a large ensemble, would have been heard with the road show release, and is available on earlier DVD releases. Rodney Sauer of the Mont Alto Motion Picture Orchestra has created a score consistent with what would have been available to a smaller (in this instance, six-piece) group of musicians for the film’s general release.

Ah. Oh dear. So the “orchestral score” with which this restoration is “graced” is not actually written for or performed by an orchestra. It’s a score compiled from existing material, arranged for a six-piece ensemble. Fine. Disappointing, but fine. You clearly have a budget, and you have to stick to it. But what about the claim that the Louis F. Gottschalk score is available on earlier DVD releases? (I note that it doesn’t “grace” those earlier DVD releases.) Well, the back of the 2004 Kino DVD of The Three Musketeers states the following: “Original 1921 score by Louis F. Gottschalk, arranged and performed by Brian Benison and the ‘Elton Thomas Salon Orchestra’.” Don’t you just love the inverted commas around the name of the “Orchestra”? Because of course this “orchestra” is not an orchestra. The “Elton Thomas Salon Orchestra” is a euphemism for one man and his synthesized MIDI files. So, no, “the Louis F. Gottschalk score, orchestrated for a large ensemble”, is not available on earlier DVD releases. It’s never been available because no-one has ever used an orchestra to record it. I’ve listened to the synthetic version on the Kino DVD and I in no way consider myself to have heard “the Louis F. Gottschalk score, orchestrated for a large ensemble”. I wish I had heard it, but until I’ve heard it performed by “a large ensemble” (does this mean an orchestra, even a small one?) I reserve judgement.

Back to the 2021 restoration of The Three Musketeers, it doesn’t help clarify matters that the Mont Alto Orchestra calls itself an orchestra in the first place. The orchestra’s homepage—their equivalent, I suppose, of the DVD small print—describes them as “a small chamber group”; the roster of musicians’ biographies numbers just five. Even in the 1620s (the time Fairbanks’s film is set), a group of five or six people would blush at calling themselves an “orchestra”. The musicians we see on screen playing for the royal ball at the end of the film (there are about ten of them) form a larger group than we hear performing on the soundtrack. A century later, a small court orchestra might expect to field twenty players, while the larger ones double or treble that number. By the 1820s, a symphony orchestra was beginning to be standardized and you would hope to have forty or fifty players. By the 1920s, you might have a hundred or more players for larger orchestral or operatic works. Film orchestras of the era varied in size according to their venue, but the premieres of big films like the Fairbanks super-productions of the 1920s would have been big events with musical accompaniments to match.

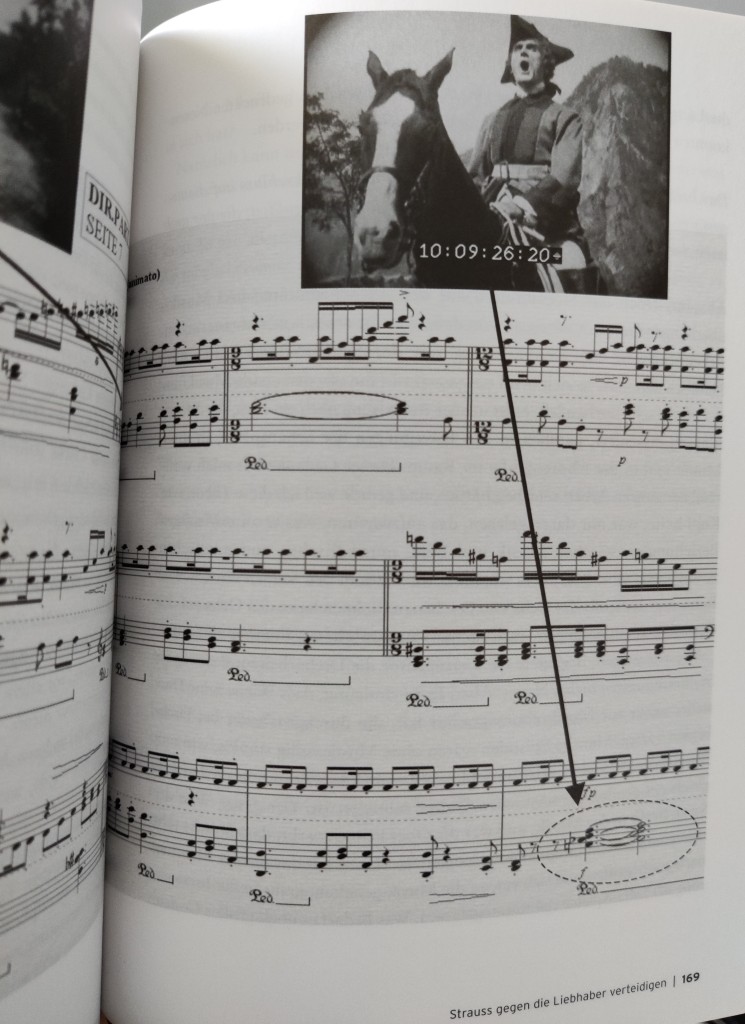

As Jeffrey Vance documents, the premiere of The Three Musketeers was a lavish event, featuring a spoken prologue and “a full orchestra” performing the score (Douglas Fairbanks, 120). Though Vance judge’s Gottschalk’s score “particularly weak in the action sequences, and utterly unable to capture the comic aspects of the action”, he also reminds us that “Fairbanks’s increased involvement with the music and exhibition of his productions began with The Three Musketeers” (ibid.). For Robin Hood, Victor Schertzinger arranged a score “for eighteen players” (ibid., 145). The cover of the 1999 Kino DVD (the soundtrack of which was replicated for the 2004 reissue) says its restoration features “the Original 1922 Musical Score in Digital Stereo”. Of course, you must read the small print on the back to see that Schertzinger’s multi-part score is performed not by an orchestra but by Eric Beheim on “a MIDI-based synthesizer system”. Schertzinger’s score (as Vance says) certainly sounds repetitive, but how can I properly judge it as synthetic pulp rather than orchestral fibre? The way to make these scores more musically viable is not to reduce them, but to expand them—reorchestrate them to make the best use of the original material. Finding a compromise too often means doing something cheaper and less complex. (As a sidenote to this, the 2019 restoration of The Thief of Bagdad uses Mortimer Wilson’s original orchestral score. This version was broadcast on ARTE a couple of years ago but has not yet received any home media release. Wouldn’t it be nice to have all Fairbanks’s silent epics restored complete with the music that their creators intended to hear?)

The Sauer score for The Three Musketeers is perfectly good, although it often lags behind the pace of the action and can never capture the scale of the film. Six musicians can’t conjure a sound world as rich and detailed as the visual sets and crowds of extras. You need an orchestra. You need something that will sweep you up in the adventure of the film. This six-piece band can only gently suggest that you might like to come along. And although the more intimate scenes in the film don’t obviously cry out for a full orchestra, I do confess that my heart sank to hear Sibelius’s heartrending Valse triste (op. 44: no. 1, 1903-04) in the reduced circumstances of a six-piece band. Only a small portion is used in the scene where Buckingham and the Queen meet for the first time, but I wasn’t moved by the scene or even by the music—I was moved by the plight of what should be a full string section of forty or more players reduced to a single violin and cello.

But much of this is, I’m sure, down to my individual taste/snobbery. I know orchestras are expensive beasts, and that hiring them and recording them is beyond the budget of most labels. I don’t mind a score for a small chamber group, but please call it a score for a small chamber group. If it isn’t being performed by an orchestra, you’re not offering us an orchestral score.

I’m sorry to have gone on so much about the score, but I do get fed up with labels overpromising and underdelivering. The Three Musketeers is still a lot of fun, and looks as good as we can hope on this new release. Here’s hoping a new restoration of Robin Hood will follow…

Paul Cuff

References

Kevin Brownlow, The Parade’s Gone By… (New York: Alfred A. Knopf, 1968).

Paul Cuff, “Silent cinema: Material histories and the digital present”, Screen 57.3 (2016): 277-301.

Tracey Goessel, The First King of Hollywood: The Life of Douglas Fairbanks (Chicago: Chicago Review Press, 2015).

Jeffrey Vance, Douglas Fairbanks (Berkeley: California UP, 2008).