I adore the soundworld of late romantic music. I have lived and continue to live in this lush, exotic, expressive, excessive, experimental realm—I spend hours every week immersed in music well-known and music forgotten. I love the great composers, but I also love the lesser-knowns. The latter appeal to my obsessive side: they are people I can hunt down through footnotes, through asides, through the marketplace outlets and only-available-as-offair-broadcast-mp3 sharers of the world. Give me your Austro-German oddities, your Scandinavian obscurities. Give me your tone poems on bizarre themes, your operas about abstract ideas, your itinerant harmonies and luxuriously strange orchestration, your dozens of weird symphonies, your books of diverse chamber works. Give me your Schrekers, your Braunfels, your Schulhoffs and Schmidts (and Schmitts!), your Atterbergs and your Langgaards. Francophone? No problem! Give me an obscure French composer of orchestral music who was born (approximately) in the latter half of the nineteenth century and died (sometime) in the interwar years and I’ll be a happy man. D’Indy? It’s a done deal! Magnard? Yes please! Rabaud? You bet! Pierné? Seconds please! I love the music of all these composers (and many more besides). What I love especially is when this music overlaps with the world of silent cinema, either in my imagination or in that of the original composer’s intentions. The instruments and rhythms of popular music of the 1910s, 20s, and 30s bleeds into the legacy of orchestral music from the nineteenth century—and the fusion produces fantastic things. And of course I delight in original silent music scores written in the era, since it introduces me to any number of more obscure composers. So you can imagine my joy when I came across the music of Charles Koechlin (1867-1950) and, in particular, a symphony he wrote that was inspired by silent cinema…

The Seven Stars’ Symphony, op. 132 (1933)

Koechlin wrote this “symphony” in 1933, when sound had conquered cinema. The stars he recalls in music thus straddle the divide between these two eras. He’s recalling the silent screen as well as acknowledging the coming of sound. Across seven movements, we get sonic pictures—or recollections—or seven stars of the screen. This is not a symphony in the classical sense, since there is no overarching unity of form or design to the work. Rather, it is a series of tone poems that conjure a musical-cinematic universe. Just as Koechlin uses one medium to evoke another, so must I use prose to try and capture his music. (Of course, you can listen to the symphony here.) I make no pretence at real analysis, offering only an impression of Koechlin’s impressions:

I. Douglas Fairbanks (en souvenir du voleur de Bagdad). We step into a harmonic world of the orient. The movement instructs us to recall The Thief of Bagdad. But as soon as we begin, we’re lost. This is not the film of 1924: it’s a dream of the film. Woodwind tiptoes up weird scales. Slow-motion strings unwind in the stratosphere. Weird curlicues perform oriental turns. Melodies bubble up and die away. There is no drama, only glittering stepping stones towards sonic dissolution. It’s six minutes of spellbinding strangeness. Nine years had passed between the film’s premiere in Hollywood and Koechlin’s score being written. A distant memory revived in sound.

II. Lilian Harvey (menuet fugue). A graceful dance, strings shining over warm woodwind. Is Harvey performing a turn on screen? What does Koechlin remember of her? A saxophone line blooms in the orchestra. The music turns chromatically sour for an instant, threatens to unwind the texture. Then this moment of drama dissipates. All ends with a dreamy slide up into silvery nothingness.

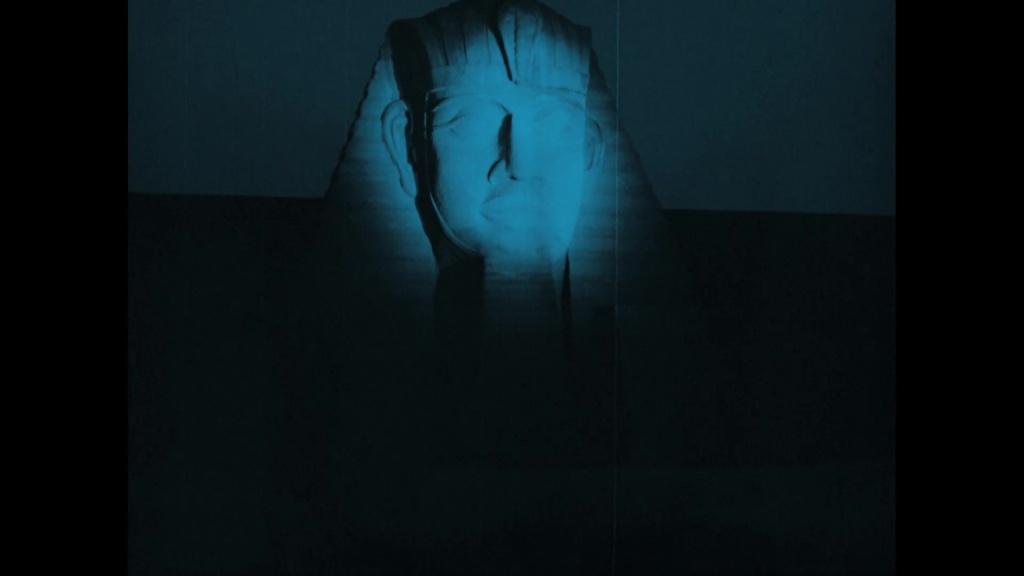

III. Greta Garbo (choral Païen). The ondes Martenot spells out something that may or may not be a melody. It’s an unstable base on which to build a movement. Woodwind tread in its path. Strings uncommittedly slide underfoot. If Garbo is here, she is as insubstantial as quicksilver. Here is her unknowability, her ungraspable form on the screen. The image does not flicker. The music is a portrait of the surface of the screen: it’s all sonic sheen, all gleaming illusion. There is no scene, hardly any form—just something slipping away, beyond one’s grasp.

IV. Clara Bow et la joyouse Californie. Bustle! Brass! Light, skipping percussive steps. Here is Clara Bow, or the sonic imprint of her liveliness, her spirit. This is the first time Koechlin’s orchestra has shown real body, something approaching a full, round, sweep of sound. It’s more harmonically traditional. That is, until the whole soundscape dies away. Suddenly there is a skittish rhythm and a reduced texture, a kind of circus-like dance in the distance. (In the background, a glockenspiel adds texture to the downward line of melody, then an upward leap.) Is this California? Are we on the street, a studio lot, or in a fictional world? Of course, this is all a fictional world, at one, two, three, or four removes from reality. The harmonies thin again. It’s like a pair of curtains part, revealing another vista—some way off. A saxophone ripens the melody. Then the melody unpeels into weird, restless harmonies. The whole world threatens to collapse, until the brass and strings gather together and bulldoze forward. The movement ends in a massive affirmation.

V. Merlène Dietrich (variations sur le thème par les letters de son nom). Oh my word, this is gorgeous orchestration. Dietrich in sound is more worldly than Garbo in sound. The melody unfolds on the woodwind. A repeated refrain moves slowly, turning back on itself, comes on again. If this is Dietrich, she is alone. It’s a kind of hum. (Somewhere deep in the orchestra, pizzicato double basses pick out a regular beat.) The music turns from us, departs, trailing melancholic satisfaction. (Note Koechlin’s misspelling of Dietrich’s name: “Merlène Dietrich” is surely a deliberate marker of the composer. Here is his star, his memory of her.)

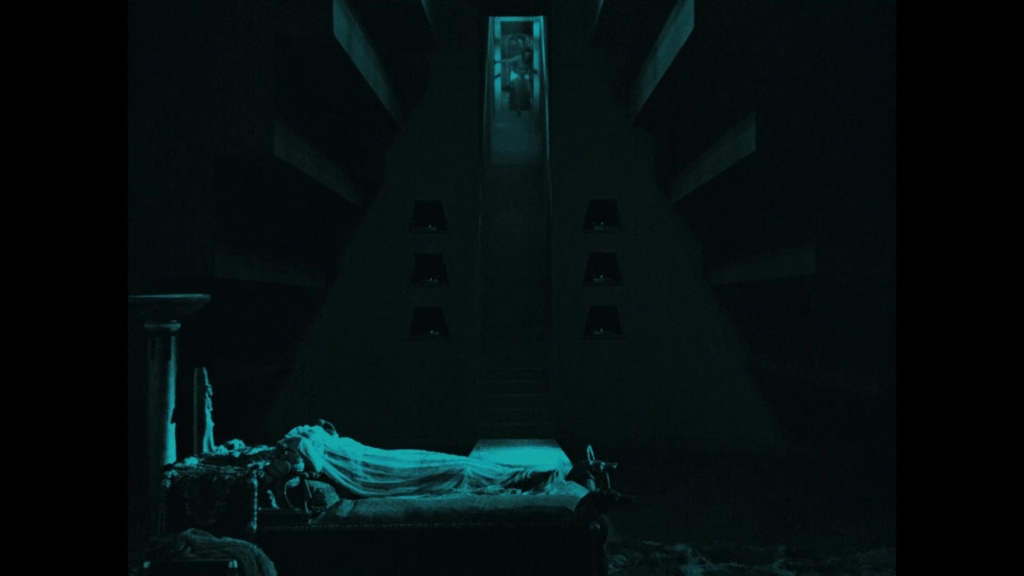

VI. Emil Jannings (en souvenir de l’Ange bleu). Growling, brooding brass. A kind of slow stomp in sound. Bitterness, darkness. Depths and weights and plugs of music. Then the strings recall some distant melody, some dim memory of pleasure, of longing that may be satisfied. The movement refers to Der blaue Engel, but not to a scene so much as a mood—a portrait of Jannings’ character as the character might himself feel before he falls asleep. Anger, resignation, memory—fading away.

VII. Charlie Chaplin (variations sur le thème par les letters de son nom). What begins melodically soon turns chaotic. Entropy enters the rhythms, the harmonies. This is Chaplin in the form of his movement, his sudden bursts of speed, of wit, of evasion. Charlie is skipping, Charlie is running, Charlie is fighting. There are bursts of exquisitely controlled fury, such that threaten to turn atonal—to wrench us into another genre. Then all is sinisterly quiet. Bubbles of noise rise to the surface, burst, and vanish. Where are we? What’s happening on screen, or in our souls? Woodwind try to rescue the mood from eerie, high-stringed harmonies. Where is Charlie? A solo violin rises from the chromatic unease, but only for a bar. Soon the unrest resumes. It’s a kind of sonic starvation, minimalism on the lookout for sustenance. Where are we? Is this winter? Is this the dawning of madness in The Gold Rush? Poverty pulls at the edges of the score, threatening to impinge on this portrait of a comic icon. Eventually, after meandering through various scrapes and scraps of scenes, the solo violin leaps up against outbursts of brass, clattering glockenspiel, sinister fanfares. Some kind of resolution is reached, and it’s hardly a happy one. Has the Tramp died? Is he on his way to heaven? High woodwind detaches itself from the ground. The saxophone freewheels in the mid distance. Odd percussive clashes are far below us. Is this the dream of heaven in The Kid? If so, Koechlin treats it as a slow, surreal scene. The orchestra appears to waken. All is bleary, unsure of itself. The solo violin recalls something, leaves behind the other strings. Finally, a determined little march: woodwind steps, one-two, one-two, one-two; pizzicato strings, one-two, one-two, one-two… To where are we heading? Toward silence. The little march fades into the distance. Is this the end? Just as it seems as though silence is the answer, the whole orchestra rises into an enormous crescendo of sound: an apotheosis that towers over the preceding caesura, as if spelling out an enormous intertitle on screen—“THE END”!

What an absolute delight this music is. The orchestration is as lucid and precise as that of Debussy but anticipates later work by Messiaen. It’s lush and rich yet teeters on the brink of atonality. By turns gossamer light and terrifying dense, soothing and scarifying, evocative and vague, particular and meandering, this score is everything I love about late romantic music.

But how might we understand the relationship between The Seven Stars’ Symphony and the cinema that inspired it? Koechlin is surely more interested in these stars as starting points for music, as representatives of cultural moods and manners. In conception, the symphony reminded me of Roland Barthes’s famous essay “The Face of Garbo” (in Mythologies, 1957). I don’t just mean in the sense that, in Barthes’s words, “The face of Garbo is an Idea”; but in the way both treat Garbo as an excuse to produce delightfully vague and suggestive evocations using the actress (or rather, the image of the actress) as their starting point. Though Barthes had recently re-encountered Garbo in a revival of Queen Christina (1933) in Paris, he too was surely relying on memories—not just of films, but of images and associations. The distance between star and spectator itself becomes the subject of interrogation. Barthes is not interested in the history or life of the star so much as her symbolic function in (an exceedingly ill-defined conception of) cinematic history:

Garbo still belongs to that moment in cinema when capturing the human face still plunged audiences into the deepest ecstasy, when one literally lost oneself in a human image as one would in a philtre, when the face represented a kind of absolute state of the flesh, which could be neither reached nor renounced. A few years earlier the face of Valentino was causing suicides; that of Garbo still partakes of the same rule of Courtly Love, where the flesh gives rise to mystical feelings of perdition.

Koechlin’s music allows the listener to become as “lost” in Garbo-as-sound as one might be “lost” in the image of Garbo-on-screen. Koechlin’s symphony is the product of a kind of fandom: an expression of his encounters with Garbo in film. But it’s also an analysis of that experience: a musical exploration of the idea of cinema. The Seven Stars’ Symphony offers a glimpse of the afterlife of stars within the imagination of contemporary viewers. Images become sounds, cinema becomes music.

As well as these more abstract thoughts, the symphony also makes me want to ask more practical questions. How often did Koechlin visit the cinema, and where did he go? What films did he see in the silent era, and in what circumstances? (I would buy the one and only book on the man to find out more, but it’s been out of print for decades and will currently set you back the best part of £200 to get it. My curiosity can wait.) As so often, the cinematic life of artists who lived through the silent era is frustratingly obscure. How often have I wanted contemporary writers and painters and composers to have left accounts of everything they saw and heard… Of course, Koechlin’s symphony is itself an account of his experiences, even if only the abstract impressions left on him by the cinema. His seven studies are mood pieces, fleeting glimpses of life and stillness and movement on screen, of rhythms that might have been seen or heard or felt at the cinema. Koechlin’s extraordinary orchestration offers us a way to explore cinematic impressions through sound, to let the transmuted forms of one medium live again in another. By any measure, with or without a filmic context, The Seven Stars’ Symphony is a glorious sonic experience. Go listen to it.

Paul Cuff