Until recently, it was most common to see silent Soviet films via the versions circulated by Mosfilm or Gosfilmofond that originated in the late 1960s-70s. There is a familiar kind of soundtrack: a giant orchestra, crammed into a thin mono recording. In these confines, the music seems to warp and wobble rather than reverberate. The scores tend to be aggressive, brooding, threatening—with the noise of real gunfire thrown in for good measure. They often sound like cobbled-together Shostakovich (and sometimes are) but more often feature music by a composer you’ve never heard of whose name is uncertainly transliterated from Cyrillic into the Latin alphabet in the “restoration” credits. (Did the composer of the 1969 score for Vsevolod Pudovkin’s The End of St Petersburg (1927) wish to be called “Yurovsky” or “Lurovski”? I still don’t know. Confusingly, his son—the conductor Michail Jurowski—went by a different spelling, as do the conductor’s own sons, also both conductors.) Some of these Soviet recordings have very effective, and affecting, passages. The opening few minutes of Alexander Dovzhenko’s Zvenigora (1927)—in a restoration from 1973(?)—is among my favourite in all Soviet cinema: super slow-motion riders pass before a screen of trees, as a hushed, yearning pulse of music flows beneath. Image and sound grip you instantly. It’s a hauntingly beautiful opening shot. (The rest of the film rather loses me.)

But the film historian is on dodgy ground with these 60s-70s versions. The way these copies are curated for our use severely interferes with their historical status. Where are the original credits? Are these the original titles? Is there any missing footage? And what of the music? Were scores assembled especially for the films? Was the music original or arranged? Was it any good?

These questions are commonly asked about many works of musical theatrical history. Take opera, for instance. I was recently relistening to Halévy’s La reine de Chypre (1841). No single edition of this grand opera is “definitive”, in the sense that it underwent continual editing throughout its time on stage. Even during rehearsals, music would be cut or added or rewritten. Sometimes, this complex, often last-minute work was too much for Halévy himself, so he outsourced parts of the orchestration (or even the composition itself) to an assistant. New arias were inserted at the behest of singers, new passages of intermediary music at the behest of stage managers. And all this was without any of the score being printed in full. The “performing edition” of the work would exist across a wide range of documents: parts for the orchestra, the conductor, the composer. Many of these would be notated only in shorthand, overlaid with numerous manuscript corrections or instructions from conductor or composer as they worked on the production. Once the run of performances had ended, this array of paperwork would end up in various collections, often being scattered in the process. If the opera was produced elsewhere, it would undergo further changes and produce further paper trails. Even if all of this paperwork survived, the result is a kind of collective palimpsest with competing and conflicting evidence for what the score should be. Thus, there are always editorial choices to be made with historical material. The musical content of La reine de Chypre shifted across time, never being the same from one season to the next. So when the opera was “restored” in the 2010s, there was a huge range of choice regarding what music to include or exclude from the recording. (There would also, inevitably, be budgetary considerations: recording all the various possible numbers, even for an appendix on a bonus CD, would dramatically increase the cost of the project.) So when a new “performing edition” was created and then the recorded in 2017, a lot of music that survived in various sources was excluded (the overture, the ballet, the gondoliers’ chorus…).

This complex textual history is paralleled in the world of silent film music. Even if an original score existed, its survival is subject to all the same processes as might affect an opera score: different editions of the film for different markets, or for subsequent revivals; paperwork for different scores produced by different musicians for different cinemas etc. It follows that the question of a silent film’s musical restoration is as complex as that for its visual restoration. But how often does the same level of attention get paid to the music as to the image? And how often is this issue of musical reconstruction even acknowledged or addressed by the studios who own the films or the companies that release them on DVD? Whereas the Palazetto Bru Zane release of La reine de Chypre on CD in 2018 is accompanied by a fabulous book, including essays on the work’s genesis, reception, and textual history, most silent films do not get anything like this kind of documentation. Instead, there is the familiar blurb boasting “original versions” of this, and “complete restorations” of that. The word “original” and “complete” are rarely qualified, and even in cases where they are most appropriate, they never tell the whole story.

In relation to October (1928), the work of Edmund Meisel (1894-1930) and Bernd Thewes (b.1957) is an interesting case in point. Thankfully, the Edition filmmuseum DVD (2014) is as good as it gets when it comes to documentation. All the issues mentioned thus far are addressed, qualifying the selling point of this edition as featuring “the original orchestral score by Edmund Meisel”. As Richard Siedhoff writes in the liner notes:

[O]nly the torso of Edmund Meisel’s body of film music survives. Not only was the archiving of films and music not common practice at the time, but with the ascendancy of sound films, interested in the music of silent film composers waned precipitously. In the few cases where the ‘original music’ for silent films has survived at all, it is only as piano sheet music or as incomplete, handwritten orchestra parts. Musical directors in cinemas used the piano music as ersatz scores, since they were easier to work with than full scores. So full scores were almost never printed and when a film was no longer in distribution, the orchestra parts were stored somewhere or sometimes simply destroyed. […] [W]hat we have of [Meisel’s] film music comes from piano sheets, for which new instrumental arrangements have been written, and which have been adapted, re-arranged, lengthened and re-defined for longer versions of a film.

This is an orchestral score for October, but one whose orchestration has had to be rearranged by a different composer. It is both a score by Edmund Meisel and a score by Bernd Thewes. Not having a complete picture of how Meisel arranged his music, we must give credit to Thewes for filling out the sound world that survives on Meisel’s extant staves. What we have now likely offers a much better listening experience than for audiences in 1928. As Siedhoff writes of Meisel’s scores: “Prepared in a great hurry at the time, they are riddled with mistakes. Working from them in live performance must have ranged from torture to total chaos.” And while Meisel worked with Eisenstein’s approval on both Battleship Potemkin (1925) and October, Eisenstein would ultimately break off contact with the composer over the presentation of October (claiming Meisel had it projected deliberately slowly to aid his music).

So, talking about the way this music sounds when performed is a complex issue. I do no propose to write a piece on the whole film and score: it would exhaust me to write it as much as it would you to read it. Besides, while the film is a baroquely dazzling exercise in filmmaking, it wears me out after about 45 minutes. The images are always superb, but the drama loses me. This is where music can make such a difference. The Meisel/Thewes score for October kept me engaged musically even when my interest in the drama dwindled.

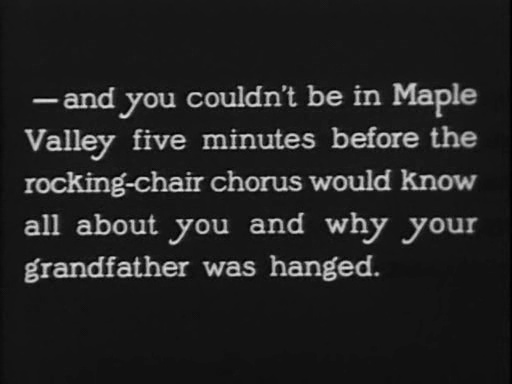

I want to write about the sequence which seemed to me the best combined use of image and music in the film—or rather, the scene where this combination gave me the greatest pleasure. It begins about 25 minutes into the film and shows Kerensky, the head of the provisional government, heading into the Winter Palace to assume his office.

We see three men, their backs to us, advance down the hall. The shot is slightly undercranked, so that they seem to waddle at speed rather than walk or march. The first shot doesn’t show their faces, and in the second shot they are so small as to lack features. Eisenstein makes them tiny in the palatial spaces, miniscule dictators. Meisel knows the scene for what it is: it’s comic, absurd, playful. It’s also repetitive and surreal. We see the endless columns, the endless arches, the endless steps, and the figures’ endless movement along and up, and up—and up. So Meisel spells out a musical beat that is both steady, banal, but almost too fast: it’s as though we can hear the men waddling at speed through the score. And Meisel/Thewes knows exactly how to get the best out of the rhythm. Below pizzicato strings, the main two-note figure of this section is played on the trombone, an instrument whose low, slightly bluff sonic roundness gets a lot of use in comedic film scores. The performance (I cannot speak of the score as written or notated) plays this up: there is a certain sliding in the transition between notes, giving this simple beat a sense of being out of breath, ever so slightly out of balance. The shape of the beat (descending phrases: one-two, one-two, one-two-three-four) suggests a kind of effortful trudge as much as a triumphant march.

Then, as we cut from a title (“The dictator”) to a closer view—but again from the rear—the strings take up the two-note step of the beat and the trombone and brass start to warm up into a kind of fanfare, supported now by the martial crash of drums. The trio of generals ascend the stairs.

Another title: “Commanders-in-chief…”. So now the strings develop the beat into a melody, albeit equally simple and just as repetitive. They are supported by the snare drums and, deep below them, the great blast of the tuba. It’s a pleasingly bombastic development of the initial musical idea, but it’s still deliberately simple—you can spell out the one-two-three-four of the beat, the tuba joining in for the first and third note. The tuba has the same role as the trombone in the first few bars of the scene, only it now amplifies the pompous oom-pah, oom-pah rhythm of the generals’ footsteps.

For the generals are now ascending a giant marble staircase, and Eisenstein distends the time it takes them to climb. First we have a long shot from the right side, looking left; then a title completes the information begun in the previous text: “…of the army and navy”, before a view from the left of the staircase repeats the same pattern of movement. Up the stairs they go, as the music builds in volume. (Another title: “Prime Minister”). Eisenstein cuts closer, but again so that we see only the backs of the commanders. At this point, the snare drums double their speed below the rhythm of the brass, as if to say: keep going! keep going! The trombones are now given a delicious upward swing to keep step with the drums’ quickened pulse.

Having cut closer, Eisenstein then cuts further away: the officers are still ascending, and it becomes clear that he’s making them repeat the same steps as at the end of the previous shot. As he does so often in October, Eisenstein uses montage to make successive shots overlap in time: space is made subservient to time. Just as we start to appreciate how elaborately the upward march of the generals is developing, an intertitle cuts in: “And so on, and so on, and so on.” But the text, too, becomes a visual joke: you read it from top to bottom, each line successively indented so that the phrases take the form of steps. Disconcertingly, you are reading the text from left to right, top to bottom, while each line moves further to the left as you go down: the way we read the text is moving in the opposite direction to the way the figures are moving on screen. It’s an extraordinarily complex visual/textual joke, and a brilliant way to make the intertitles graphic in a meaningful way.

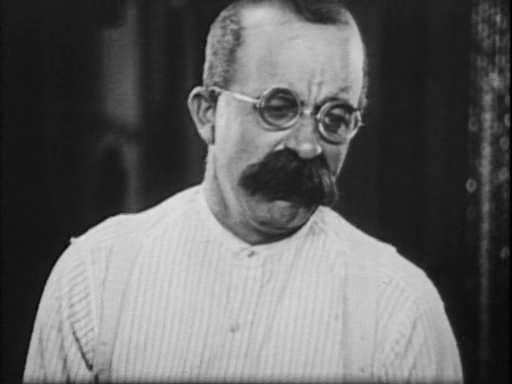

Cut back to the stairs, now viewed from another angle, and this time we see the generals from the front for the first time. We cut from the stairs to the statues that overlook the figures. Stone hands hold out crowns of laurel, and the cutting seems both to join in with the march but also break it, or even to anticipate its culmination at the top. “The hope of the Fatherland and the revolution—” a title announces, and the statues are seen from below, from disconcerting angles, mirroring one another, as if they might topple over us. After the next title: “A.F. Kerensky”, we finally get a close-up of a human face. But this too is disconcerting, threatening, surreal. For it breaks the rhythm of ascent, the continuity being built up (however playfully) in the previous shots: here is Kerensky glowering down into the camera, leaning brow-first into the lens, the angle of his head and the side lighting transforming his face into a kind of arrow pointing at us. Eisenstein cuts to the statues bearing laurels, and a train of thought seems to dance across the screen—for Kerensky breaks into a smile, but a smile made sinister by the deep shadow in which it is formed.

And now—well over a minute into the sequence—we finally see the top of the stairs! A line of lackies looms from the shadows in this cavernous space, a space which—though we have seen so many shots of its details—surreally escapes our full comprehension. How exactly is the staircase arranged? Is there one set of steps, or are two sets of steps facing each other? And where are the steps leading? How high have we climbed, how many flights of steps?

“The Tsar’s lackeys”, a title announces. (And the film’s titles are always faintly sarcastic, mocking, whenever they aren’t slogans or exclamations or punctuation points.) A large man, whose uniform bulges with his bulk, steps forward—and the statues seem to look down on him, the statuary of the imperial past, the dark columns made defy gravity by the camera’s tilted angle. There are salutes seen from close, from afar, from close; time overlaps, gestures overlap, formalities pile into one another, pile onto one another. Their handshake takes an age, it’s captured in one, two, three, four, five different shots—emphasizing the lacky’s subservience, Kerensky’s effort to look imposing, and (cumulatively) the sheer awkwardness of a handshake that lasts this long.

Kerensky moves on, and the musical rhythm shifts once again. It grows in subdivision, the same foursquare beat now marked with the tuba spelling out all four notes in the bar. And listen to the strings in conjunction with the added brass: there’s such a glorious swing to the way the music is played, sounded out. The bright notes of a glockenspiel punctuate the rhythm; the notes are like shining medals, buttons or baubles catching the light. And it’s a marker of how beautifully orchestrated the sequence has become: listen to the sense of acoustic depth here, from the dark blasts of the tuba, through the swell of strings, the rasp of snare drums, up to the gleam of the glockenspiel. It’s such an intelligent piece of musical texture. You sense both the cavernous space of the hall, the near-dark extremities of the palace—and also the sheen of manservants’ buttons, the jingle of medals on the lackey’s chest.

“What a democrat!” the title says, as more handshaking takes place. Every servant is greeted, every servant nods happily to the next. The shaking is seen in close-up, from a distance, from close-up, from a distance… It’s an endless sequence made even more endless the way time and space overlap, the way the editing repeats and moves restlessly back and forth. And all the while, the orchestra is growing in volume, warming to its swing. It’s still the same, simple idea: four ascending notes that are repeated (one-two-three-four, one-two-three-four), followed by a three-note phrase that rounds off the tune. Thus, even the music (like that earlier intertitle) spells out the steps and (in its last three-note phrase) a kind of subservient bow, a satisfied execution of an about-turn before the four notes of the march climb once again. Both the visual and the musical halves of this scene could be extended forever, ad infinitum. Only the little variations keep it all building: visually, there are the various stages of the staircase, the titles, the lackeys that give the repetition a kind of crescendo; and musically, the tempo shifts and orchestration build the simple motif into a great movement of sound.

Finally, Kerensky has shaken hands with everyone, and the two commanders take the final steps behind him. Listen how that last three-note phrase of the melody now becomes a five-note phrase in the brass: one-two-three, four-five—and then a six-note phrase: one-two, three-four-five, six. It’s a simply delicious little development; the steady step of the music is becoming a skittish skip, as though the march is about to break into a dance. It’s ludicrously infectious.

“The democrat at the Tsar’s gate.” Kerensky approaches the doors to the inner palace. The anticipation is both built and suspended through editing: Kerensky’s hands clasped behind his back; shots of coats of arms on the door; shots of lackeys nodding, winking to each other; shots of Kerensky’s boots; shots of the generals; and then—in a dazzlingly strange cutaway—we see a spectacular mechanical peacock unfurl its wings, then spin around to show us its backside. Even the bird’s movement is split, repeated, made gloriously weird—close-ups of wings, feathers, feet, face—and rhymes with the turning heads of the servants, the spinning salute of the lackey, the upturned faces of the commanders. The gates open across one, two, three, four shots (wide shot, closer shot, close-up, tighter closer-up; in each shot the movement of the door is pushed back a few frames to be seen again), and the music now slows—the beat is the same, but the tempo slows by at least half. The musical march sinks back into the tonic with an ecstatic sigh—of relief as much as anything. You realize how tense this sequence—visually and musically—had become. How much longer can out satisfaction be denied? Just as the generals are climbing the steps, the music has been chromatically climbing its way through the march, creating a tonal tension that needs resolving—and is only resolved in these final bars, when we see the gates open and then shut behind Kerensky. The last bass note is allowed to extend out over the final images of the scene: the massive locks of the gates, the image of the sealed doors. In one sense, it’s like the echo of the shutting doors reverberating through the palace. But because this is a purely musical resonance, it attains a heightened sense of strangeness. It’s a kind of afterglow, a dark, ominous extension in sound. This kind of moment doesn’t exist in a paper score; it exists only when music is performed. It’s emotive, intelligent, brilliant musicmaking.

The whole thing reminds me of another joke built on similar musical-dramatic ideas in Offenbach’s La Grande-Duchesse de Gérolstein (1867). At the end of Act 1, the little state is preparing for a pointless war with its neighbour. The sword belonging to the Duchess’s late father is ceremoniously carried before the assembled forces. She sings an area, “Voici le sabre de mon père”, accompanied by the chorus. Offenbach repeats the individual blocks of the line: “Voici le sabre, le sabre, le sabre, le sabre de mon père!” The Duchess points to the sword, sings several lines to the same melody, before the chorus likewise repeats the main refrain several times to the same text (the libretto merely describes their line as: “Voici le sabre etc.”). Then the Duchess picks up the sword and repeats the exact same musical passage she’s just sung, with only moderately different words, before handing the sword to her favourite soldier. The voices of the chorus don’t even get this much variety, now repeating their first chorus wholesale. The joke is in the repetition, and in the banality of the tune extended ad infinitum in ludicrous martial pomp. But the best bit is at the very end of the act, when the soldiers are marching off to battle. “You forgot my blessed father’s sword!” the Duchess cries, whereupon the poor chorus must strike up the same melody again. Offenbach and his librettists (Henri Meilhac and Ludovic Halévy) are making the same joke, to much the same end, as Eisenstein and Meisel. Film and operetta give us martial music and pompous scenery, continually inflated and endlessly repeated, to highlight the paucity of the ideology that underpins them. Puffed up with its own vacuity, it becomes bathetic.

Having now watched this sequence about forty times, and listened to it about a hundred times as I write, I grow more and more impressed by how well it’s put together. The Meisel/Thewes score makes a tremendous impact, and is by far the best way to experience this film. The soundtrack for the DVD for October was recorded at a live screening of October in Berlin in 2012. There is often something disconcerting in live recordings of music for silent films (I’ve written about this issue elsewhere). But this recording is excellent. You get the sense of excitement in the orchestra at the climaxes—the great benefit of live performances—with minimal acoustic interference from the performance space. Indeed, the only such instance is at the final’s final chord when there is a great burst of cheering and applause—which is a lovely way to end the experience at home, and links your own enjoyment of the film with that of the audience in 2012. It reminds us that what we’re watching was and is meant to be experienced as a live event, performed by musicians and theatre staff, in front of a large audience. It’s why I love silent cinema.

Paul Cuff