It’s the last night of 2025, so what better moment to talk about the passing of time, about loss, and about transcendence. (Such is the mood of looking back here that in my first attempt at the above sentence I wrote “…the last night of 1925”.) I’m also going to indulge in something a little self-indulgent in writing primarily about recorded sound. But I hope to do so in a way which both springs from silent cinema and returns to the notion of early film history. Yes, this week I want to write about the Hungarian pianist Ervin Nyiregyházi (1903-1987).

I came across the name of this obscure artist while searching for a piece of music that I will later discuss here. So transfixed was I by various snippets on youtube that I bought Kevin Bazzana’s wonderful book Lost Genius: The Story of a Forgotten Musical Maverick (2007). Bazzana (who also wrote the classic biography of Glenn Gould, a much more famous eccentric pianist) traces the quite astonishing journey of Nyiregyházi from imperial Budapest at the dawn of the century to old age in America in the era of digital recording.

Nyiregyházi was a child prodigy whose gifts prompted distinguished teachers to develop his talent. These mentors were young enough to have been taught by the legendary composer-pianist Franz Liszt – or by those who were themselves taught by his pupils. To a child that could sightread anything, and was already composing prodigiously, they enhanced Nyiregyházi’s technical ability and expanded his knowledge of the piano repertoire. Not yet a teenager, Nyiregyházi was performing concerts with the most famous conductors and orchestras of his day, touring within and beyond Europe. By the 1920s, he was trying to make his name in America – but was already falling out with the managers and promoters who were shaping his career. Addictive traits – especially in the form of sex and alcohol – were also eroding his personal reliability. In concert, Nyiregyházi became known as a “second Liszt” not just for his astonishing technical virtuosity, but for the perceived radicalness of his interpretations – and the sense of something faintly mad in his whole persona. There was something ungovernable and perverse about the way he played music, about his whole way of living. One witness to Nyiregyházi in America was Arnold Schoenberg, who sought out Nyiregyházi with a great degree of scepticism, but found himself transfixed by “a pianist who appears to be something really quite extraordinary”:

I have never heard such a pianist before… First, he does not play at all in the style you and I strive for. And just as I did not judge him on that basis, I imagine that when you hear him, you too will be compelled to ignore all matters of principle, and probably will end up doing just as I did. For your principles would not be the proper standard to apply. What he plays is expression in the older sense of the word, nothing else; but such power of expression I have never heard before. You will disagree with his tempi as much as I did. You will also note that he often seems to give primacy to sharp contrasts at the expense of form, the latter appearing to get lost. I say appearing to; for then, in its own way, his music surprisingly regains its form, makes sense, establishes its own boundaries. The sound he brings out of the piano is unheard of, or at least I have never heard anything like it. He himself seems not to know how he produces these novel and quite incredible sounds – although he appears to be a man of intelligence and not just some flaccid dreamer. And such fullness of tone, achieved without ever becoming rough, I have never before encountered. For me, and probably for you too, it’s really too much fullness, but as a whole it displays incredible novelty and persuasiveness. […] [I]t is amazing what he plays and how he plays it. One never senses that it is difficult, that it is technique – no, it is simply a power of the will, capable of soaring over all imaginable difficulties in the realization of an idea. – You see, I’m waxing almost poetic. (qtd in Lost Genius, 9-10)

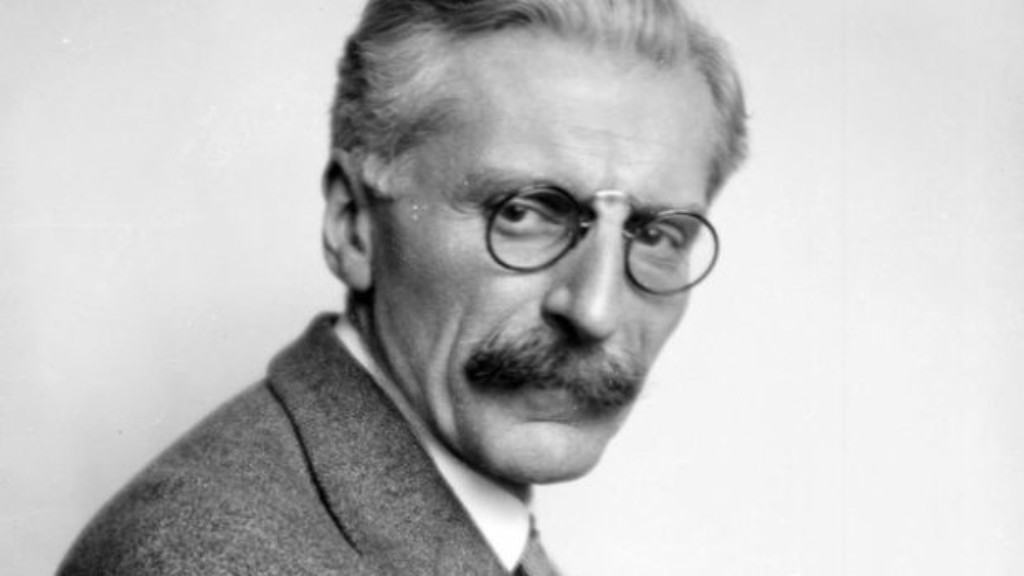

I too will wax poetic a little later, but I must reassert the connection between all of this and silent cinema. For in 1928, Nyiregyházi moved to Los Angeles and became involved in film music after contacting the prolific composer and arranger Hugo Riesenfeld. Riesenfeld was a major figure in the silent era, and he continued his work for film into the sound era. Alongside Riesenfeld, Nyiregyházi was involved in creating the music for the synchronized productions Coquette (1929) and Lummox (1930). Alas, I cannot find either of these films, so their tantalizing glimpse of Nyiregyházi’s work at this time remains obscure to me. Equally invisible is his work playing music on set and in sound studios to aid the work of various arrangers and technicians during production.

Nyiregyházi was also exploited as a performer for early sound films. His involvement with Fashions in Love (1929) is precariously preserved. The film itself is seemingly lost, but the Vitaphone soundtrack survives. (The first half can be found online here, and the second half here.) Nyiregyházi’s playing can be heard in the opening of the first part, presumably over the credits; then from six minutes for about ninety breathtaking seconds. (There is a song performed later, which may or may not be him playing beneath the rather warbly voice of Fay Compton.) You can also see The Lost Zeppelin (1929) and witness his performance of Liszt. In these instances, he is quite literally pushed into the background, a pertinent metaphor for his subsequent oblivion from music (and film) history across the central decades of his life. Curiously, by 1932 Nyiregyházi found himself playing to audiences in the cinema itself. Film journalist Louella Parsons encountered his playing at the Paramount Theater in June 1932, a live musical act now divorced from the films themselves.

Nyiregyházi’s own taste in film is curious. He himself professed a love for lowbrow cinema: “the worse the better”. His favourite characters in film were Sherlock Holmes and Zigomar (Lost Genius, 149n). Bazzana makes little of this anecdote, but the mention of Zigomar takes us back to the extraordinary crime serials of the 1910s. I love the idea of the young Nyiregyházi taking in the bloodthirsty Zigomar films in some dingy Austro-Hungarian cinema in the 1910s, and the fact that he might recall such an encounter with film so fondly. (I also wonder what Nyiregyházi’s sense was of the music being performed at such screenings. And did he ever find himself accompanying a silent film?)

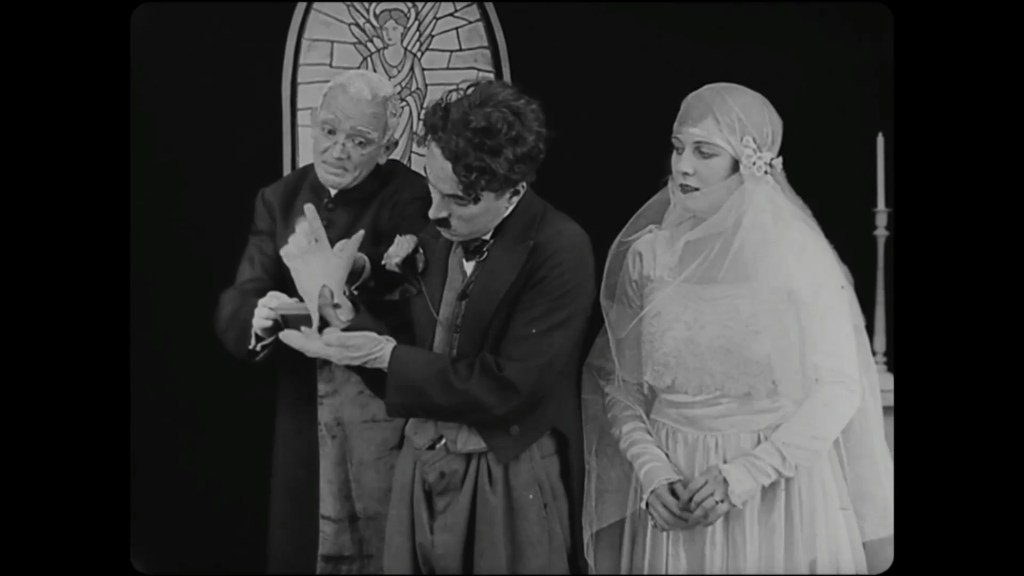

This is not the only evidence of his taste in film. Around 1935, Nyiregyházi began compiling a book of essays he called The Truth at Last: An Exposé of Life. This bizarre assemblage of reminiscence and opinion included an essay devoted to Charlie Chaplin – or rather, as Bazzana notes, on “Charles Chaplin”. This was the distinction Chaplin himself variously made between “Charlie” the performer, the clown, the character, and “Charles” the artist, the writer, the director. Nyiregyházi clearly understood the difference, for it was as a social critic that he admired Chaplin. He described Chaplin’s comedies as “tragic as hell, as tragic as anything Dostoevsky ever wrote” (Lost Genius, 170). Noteworthy also is the fate of this essay, and the whole collection of The Truth at Last. In 1957, Nyiregyházi’s seventh wife, Mara, stole the manuscript (along with some of his compositions) when she was deported to Switzerland after facing various criminal charges. By then, Nyiregyházi himself was approaching a personal low point. His career had ceased to exist, and he battled with alcoholism and homelessness. Sleeping on park benches, he became the very kind of tramp Chaplin played on screen.

What I want to draw from the above is the fragility not merely of musical artistry, but of the media that might sustain that artistry. In the case of Nyiregyházi, an entire lifetime of work is essentially lost. When he was able to perform and record his work in the last years of his life, he was both the same man and a ruin of his former self. The survival of the artist is no guarantee that their art survives. What remains of Nyiregyházi’s work when he was in his prime is fragmentary in the extreme. The scraps of music-making that survive in films of the late 1920s and early 1930s are meagre clues as to the body of work that preceded them. A wider point might be made that the synchronized soundtracks of late silents and early sound films are both marvellous documents of earlier film music traditions and a radical distortion of what that music was.

In the 1920s, Nyiregyházi made a dozen piano roll recordings (i.e. mechanical transcriptions of his playing) for The Ampico Corp. Piano rolls were a fascinating example of early media technology being used to distribute the work of contemporary performers, including many important composers at the turn of the century. Happily, some of Nyiregyházi’s work for this medium survives. A CD release of this material from 1921-24 is (I believe) scheduled for February 2026. In the meantime, a few sample numbers can be found online. Again, mechanical reproduction is not the same as live performance, and these documents cannot offer us Nyiregyházi as he was as a performer in the 1920s. But what all such recordings offer us is a glimpse into the past – or at least, a way to imagine that past.

This whole preamble is really an excuse for talking about one recording by Nyiregyházi that encapsulates everything I’ve been talking about so far. To me, it embodies the transience of music, the memory of lost art, the humanity – and the fallibility – of performers and performances. In the late 1970s, the ageing Nyiregyházi was given the chance to record an album of pieces by Liszt. Liszt was perhaps the composer with whom Nyiregyházi had the closest interpretive relationship. His recordings from 1978 are astonishing for the personal way they handle the music. Sometimes he seems to be trying to physically destroy the piano with the force and rapidity of his fortissimo, while at other times he is so quiet and so slow that the music itself seems on the point of disintegration into silence.

In his programme for the LP release, Nyiregyházi included two extracts from Liszt’s Weihnachtsbaum (“Christmas Tree”) suite, which was written in the mid-1870s and first performed on Christmas Day 1881. The music arranges a multitude of hymns and other traditional music alongside original material by Liszt. It is designed to be relatively easy to play, but – as with so much of Liszt’s later work – it has some amazing emotional depths. The movement I want to talk about is “Abendglocken”: “Evening Bells”. To get a sense of the sheer strangeness of Nyiregyházi’s performance of this piece, I should offer you something more like a “normal” performance. Before I heard Nyiregyházi, my favourite recording was by Alfred Brendel – the pianist through whom I discovered Liszt, and one of my favourite pianists of all time. Brendel’s 1986 performance of “Abendglocken” is slower than the few other modern recordings that exist, and he brings out the emotional resonance of this deceptively simple music better than most. (Brendel was also the first to record the entire Weihnachtsbaum suite in 1951. It is amazing how similar his two performances of “Abendglocken” are, thirty-five years apart. Talk about continuity across time.)

Brendel’s performance runs to four minutes and twenty-two seconds. Nyiregyházi’s 1978 performance runs to ten minutes and twenty-two seconds. This is partly due to the slowness of his tempi, but also because he repeats the entire first section of the piece. This doubles the sense of concentration, and the affirmation of importance on this simple, delicately chiming melody. Indeed, the slowness of it starts to gently pull the music apart, as though trying to work out quite what it is – or as though marvelling at something so beautiful, wanting to handle it with a kind of awe. Just listen to how Nyiregyházi brings out the irregularity of Liszt’s regular chords, how in slowing them, stretching them, deforming them, he makes them sound more like bells – bells that must be rung by hand, by physical exertion, by bodies prone to error. Indeed, the repeat of this first section of the movement features more slurs (i.e. fudged notes) than the first run-through. These are moments when Nyiregyházi’s left and right hands seem to trip over one another, or else to smudge distinct phrases. Yet even these moments seem to make sense, to re-emphasize this performance as an act of wonderment at the music. They also suggest what is to come in the movement’s final section, played just once by Nyiregyházi, where the overlapping of hands, of tempo and time itself, is most strong.

I really do struggle to describe the final two minutes of this performance. On the recording, there is a few seconds’ caesura when you can hear the creak of Nyiregyházi at the piano, preparing his body for this last section. When his hands again rejoin the keyboard, the tempo of the music seems, if anything, even slower than what has come before. The music is a chiming of hours, a ringing of sound that carries between the delicate higher and sonorous lower tones of the piano. In some performances, the “evening bells” of Liszt’s title can sound like a domestic clock, so quickly do the chords ring. One has an impression of the music being both designed for domestic performance and a kind of encapsulation of this domesticity – a memorial to it. The music is intimate, delicate, but it is also about the passage of time – about a place and an occasion. In its place within this seasonal suite, it speaks of a night waiting for specific hours to arrive – to find oneself encountering these hours in the quiet of a winter, whether sounded by a mantelpiece clock or a nearby church. But in Nyiregyházi’s hands, the bass chord has the immense resonance of a cathedral bell, a tolling from outside one’s own world, a distant, booming, solemn tocsin from somewhere entirely elsewhere. It’s so slow that it cannot be a real bell in a real location. It must instead be a memory, an imagining, of such a bell. The higher, lighter chords of the right hand are not in synch with those of the left. There is a disjunction between two tempi, two imagined sets of bells. It is like a scene in a silent film where multiple bells are magically superimposed over one another. These are sounds from two separate spaces, two separate times. It is as though Nyiregyházi’s hands are caught between two centuries. There is hardly any other piano recording – any other single sequence of recorded sound – that I find so profoundly, uncannily beautiful.

Here, I think of two moments from Dickens’s A Christmas Carol. The first is Scrooge’s encounter with the spirit of the past, who motions for him to follow them out of the bedroom window. “‘I am a mortal,’ Scrooge remonstrated, ‘and liable to fall.’” It’s a beautiful line. And yes, here in Nyiregyházi’s performance is the liability of humans to fall, and their skill to fail – another kind of encounter with temporality. This recording captures a performance, but also a performer in time. Here there is surely a tangible, physical reminder in sound of those ageing hands struggling with the discipline of artistic form. But I also think of the very next moment of Dickens’s scene, as adapted in The Muppet Christmas Carol (1992), when Scrooge is flying towards the horizon: “Spirit? What is that light? It cannot be dawn.” “It is the past”, the spirit replies. Indeed, it is the past. It lies behind us, without us; but it is also within us, and might appear again in a form mediated by art. Nyiregyházi’s performance is an encapsulation of time, a mediation of time, and a meditation on time. It is the past, and we miraculously encounter it in our present. It reminds me of a central reason for my love of silent cinema: here we may contemplate the past, enter into a relationship with it. This is a distant world, one that lives again with us while remaining loyal to its own silence, to this absolute separation from our world.

I listen to Nyiregyházi’s recording religiously on Christmas Eve, close to midnight. Invariably I am alone in the room in my mother’s house where I spent all my holidays away from university, and where I still spend the ten or so days around Christmas. It is in the middle of the Wiltshire countryside, and in the afternoons I always spend a couple of hours walking. I leave the house shortly before the sun sets, so that I might enjoy the sense of isolation more – away from other walkers, who are usually put off by the encroaching dark. On the heights of either side of the valley, there are prehistoric burials and ancient earthworks – the work of the distant past. And there am I, in this same space, a space that is both as it was and irreversibly different. My own past lies here, in the invisible network of routes I have taken in years gone by; but this is a past that I take with me, that lives – if it can be said to live – only in my mortal form, so liable to fall. And as I return home in the dark, walking through this landscape that I have walked countless times, I sometimes find Nyiregyházi’s irregular chords sounding, silently, in my head. It is a tolling not merely for the past of others, but for my own.

A Happy New Year to you all, dear readers.

Paul Cuff