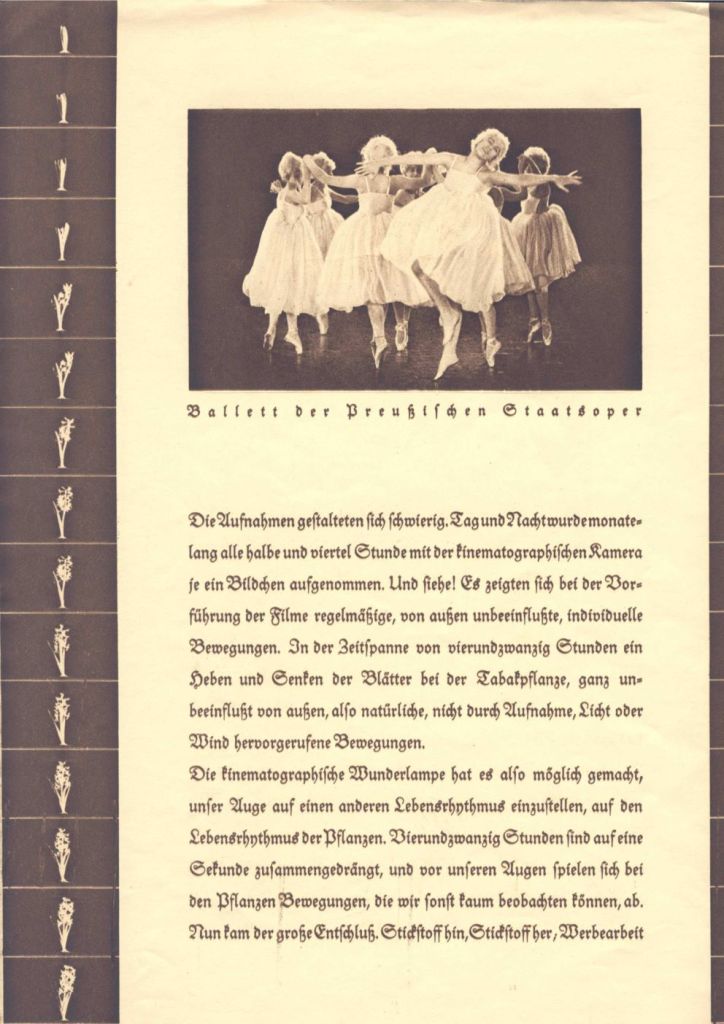

In 1921, the chemical corporation Badische Anilin und Sodafabrik (BASF) sponsored the production of a new film. BASF had bankrolled several short films with heart-poundingly exciting titles like Die Anwendung und Wirkung neuzeitlicher Luftstickstoffdüngemittel (“The application and effect of modern atmospheric nitrogen fertilizers”, 1921) and Mais-Düngungsversuch mit und ohne Stickstoff (“Maize fertilization trial with and without nitrogen”, 1923). But the film they undertook in 1921 was of a more elaborate scale and length than these earlier experimental/documentary works. At BASF’s studio-cum-laboratory in Ludwigshafen (south-west Germany), various varieties of seed were planted and painstakingly photographed, exposing one frame of celluloid at a time over a series of days, weeks, and months. It would take five years to complete this process. BASF joined forces with the Unterrichts-Film-Gesellschaft (“Film Teaching Society”) and hired an up-and-coming director to shoot additional footage and assemble the resulting material. (BASF were clearly the lead partner in all this: the chemical corporation had produced more films than the film company they engaged.) The director was Max Reichmann, who had worked as a production assistant on four of E.A. Dupont’s films: Der Mann aus Neapel (1921), Kämpfende Welten (1922), Sie und die Drei (1922), and Varieté (1925). At this end of this apprentice period, he directed two feature films—Verkettungen (1924) and Der Kampf gegen Berlin (1925)—before finishing BASF’s plant film. To BASF’s laboratory footage was added a framing narrative and ballet sequences, including some complex dissolves from plant to human movement. More than a film made for publicity or instruction (hardly counting as “cinematic” at all), this creation would be a feature-length spectacle. The stop-motion photography was the main attraction, but the film could now boast the dancers of the Berlin Staatsoper and a specially-composed score by the successful operetta composer Eduard Künneke. The film was premiered at the Piccadilly theatre in February 1926 and created quite a sensation. And what’s more, it still does…

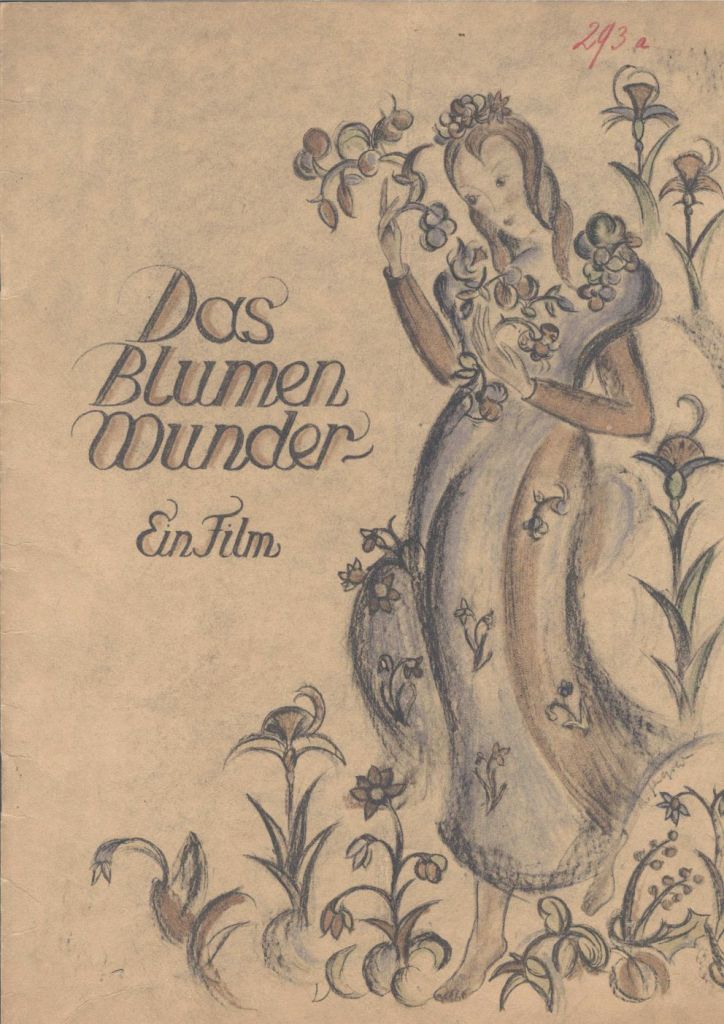

Das Blumenwunder (1926; Ger.; Max Reichmann)

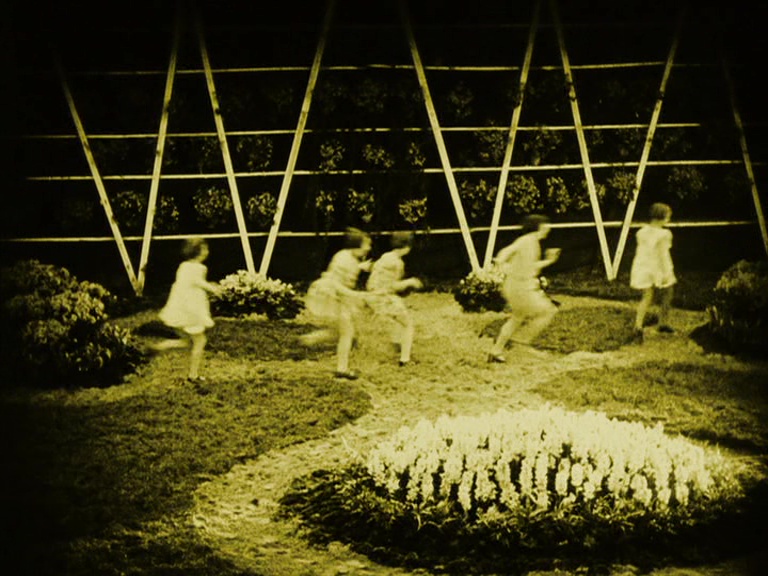

Part One. The orchestra puts its best foot forward, and we leap into the spectacle. A garden, young girls running. They dance, then pick and fight over blossom. The music is rhythmic, boisterous, stylish, skittish, jazzy. But the severing of the flowers marks a chance in tempo, mood.

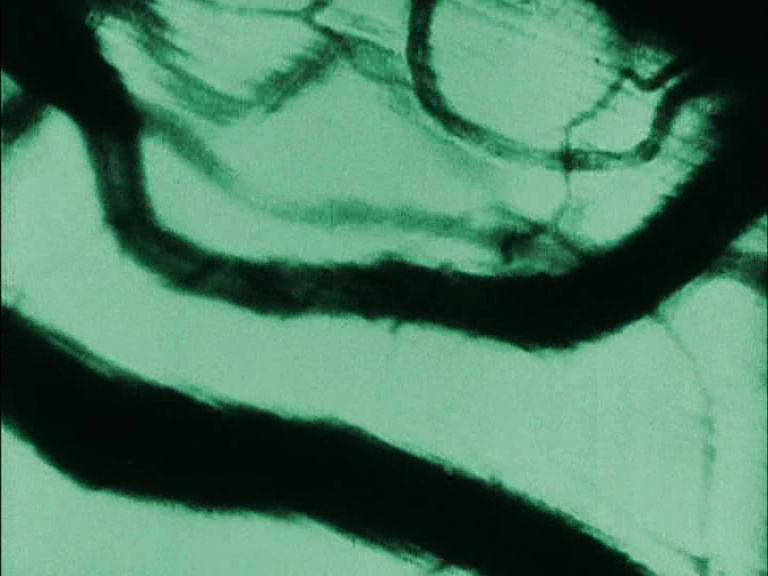

A ghostly figure appears, dissolving through the wall of foliage at the rear of the scene. She is Flora “protector of the flowers” (Maria Solveg). She explains that the flowers have life, just like the girls: “in blooming and withering they have the same feelings as you”. “Man’s rhythm of life is the pulse, the chasing of blood cells.” Flora takes the arm of a child and places her fingers on the wrist. The orchestra slows, and a trumpet gently marks out the pulse of blood. Then the timpani take over: the pulse moves deeper into the body of the orchestra. The child’s wrist moves slowly towards the camera, until the flesh begins to blur.

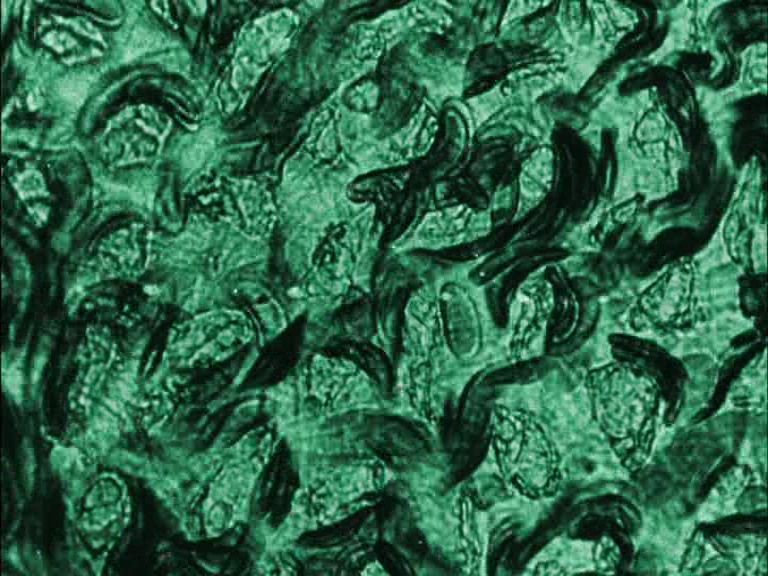

The film cuts to a microscopic view of veins, then—as the strings in the orchestra slide and glisten—a shot of blood plasma slipping through tissue. It’s an extraordinary interruption of the infinitesimal, the scientific, the biological, into the wider world of the film. It’s at once disturbing, extraordinary, and magical. The whole screen is filled with the intimate pulsing of life, the cinema with the warm pulse of the orchestra.

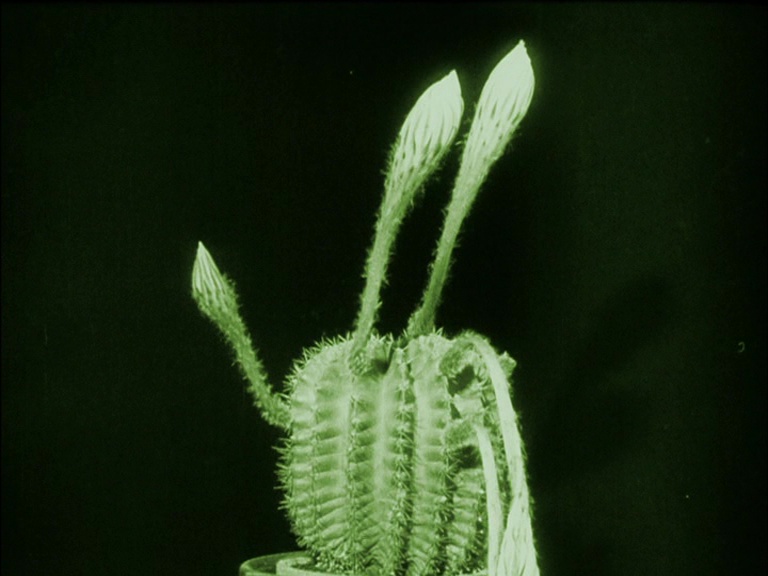

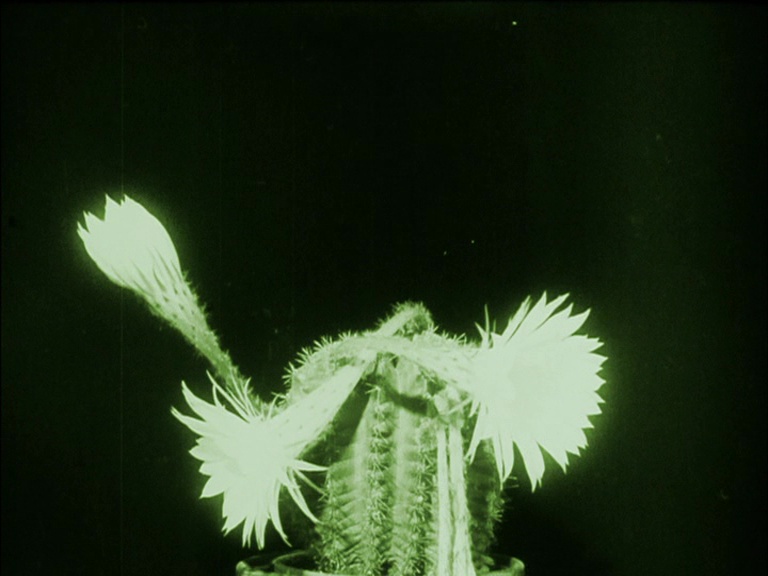

We draw back into the human scene. Flora looks up, bids the children watch the clock. We see the hands speed up, race around the dial: hours, then days glide past. “One day in the life of man is a second in the life of a flower”, she says. “The miracle of flowers will bloom before you.” And so they do. As the orchestra swells, flowers grow from the base of the screen to its summit. The buds dip and rise, like fanfaring trumpets. And just as the spectacle seems set to take off, it’s the End of Part One.

Part Two. Tobacco plants lower and raise their leaves, each lowering and raising (we are told) taking place over a 24-hour period. But each 24 hours are seconds on screen. The three plants lift, strain, grow, burgeon before our eyes. It’s a gorgeously surreal chorus line, the orchestra rising in crescendo, pulsing and growing in time to the plants.

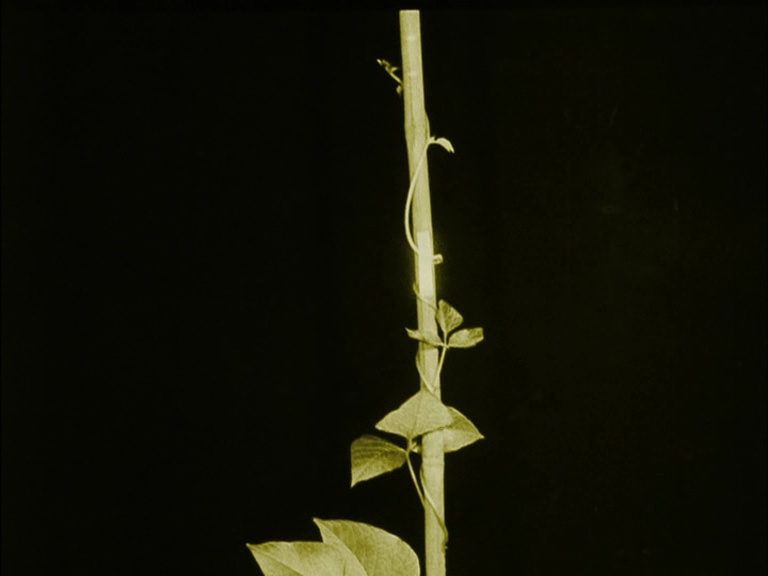

Then we see bean sprouts, the downward progress of their roots as the stem wriggles aboveground, turning 90 degrees when the box is turned. Künneke’s music shifts gear, becomes a kind of slow dance. The bean’s shoot coils around a pole, crawling its way clockwise, up and up. Even when a pair of hands tries to rewind it in the other direction, it breaks free of this imposed rhythm and winds clockwise once more. It reaches the top. The orchestra rings out. The beanstalk wiggles. It’s like the plant is taking a bow.

The banana leaf; ferns. The orchestra is also in a kind of slow-motion, reaching for a rhythm as the plants unfurl. But the vine grows quickly, reaching out to each new support: so the strings skittishly feel out a new rhythm. Another shift. The vine starts growing, lifting its heavy burden of spreading leaves. The orchestra slows, introduces a wrenching little melody for the lead violin. Suddenly the plant seems anthropomorphic: look at it stretching out, clasping at the new support, straining its sinews to reach a higher position. “It grows beyond the last support, with nothing more to cling to.” So tells us an intertitle, as if introducing us to its death. And so the next title finishes the thought: “The vines desperately circle alone, vainly seeking support, they languish and die.” But then we realize that the plant is cleverer than that, for it starts to curl and reach back to an earlier support, “where life is still possible”. We’ve seen a kind of thought process, a vegetal exercise in logic and self-preservation. So too in the next shot, where we see a vine drawing the lengths of string supports closer together to make its journey easier. Now vines clasp one another, dancing around the rival spaces: the camera cuts back to a wider shot so we can follow the upward battle for each vine. End of Part Two.

“Musical Interlude”. The music repeats that wrenching little melody, led by the solo violin. It’s slow, sweet, sad. The score is creating a mood, a feeling. With only the dark screen to see, we are now simply listening to the secret life of plants; is the film asking us to imagine our own images with the music, to reflect on what we’ve seen so far? The slow, sad dance winds to a halt.

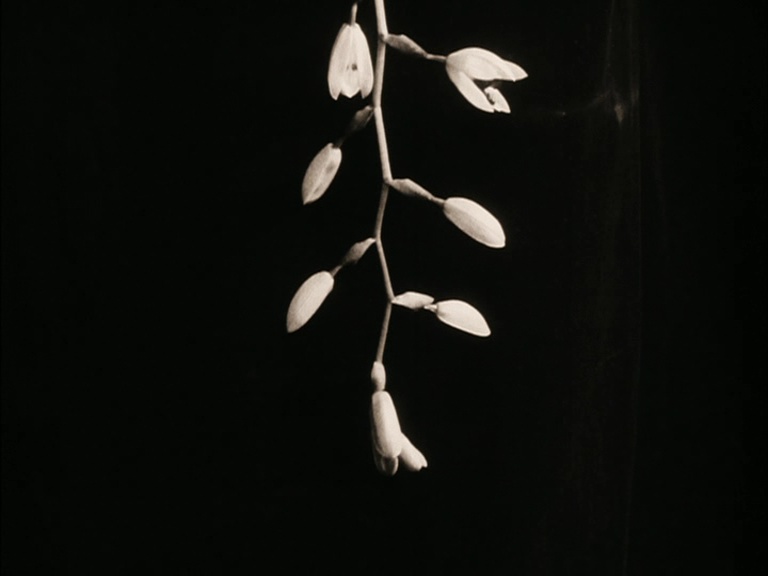

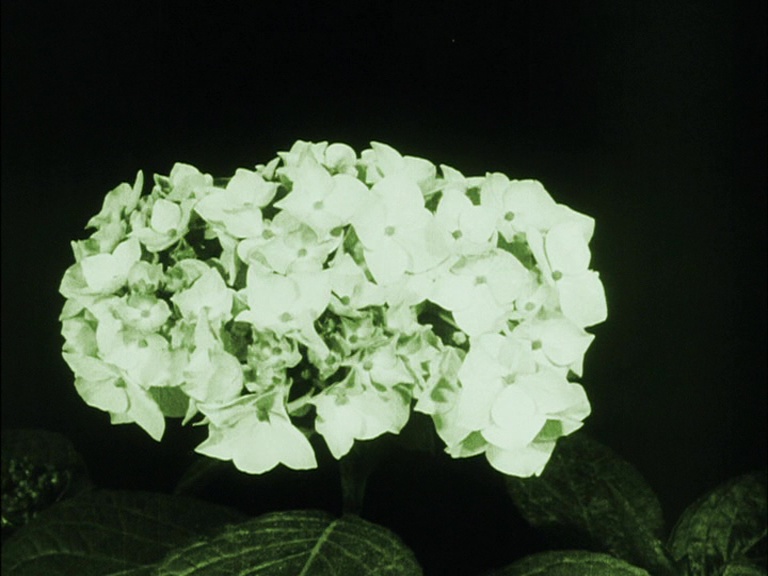

Part Three. No titles, just the glittering sound of music—glissando strings, harp, gentle woodwind—to set up the next scenes. Flowers unfold, bloom white and green against the black background. Purplish stems sprout tiny blossoms. The music reaches for high, unsettling extremes; now the leaves are dancing, and the music turns rustic, a countrified dance. Here are bluish buds, curtseying, doffing their leaves. New growths wiggle, circle, shimmer, tremble. They seem to grow faster. Fade to black. The music dies.

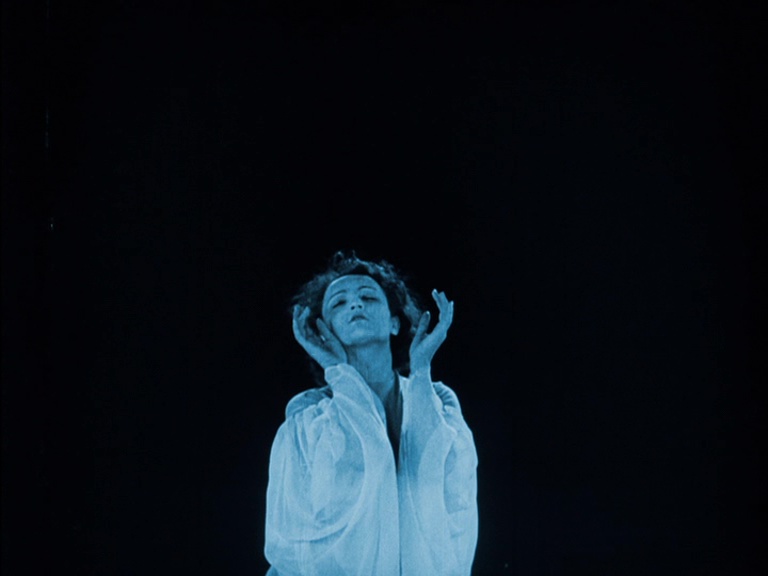

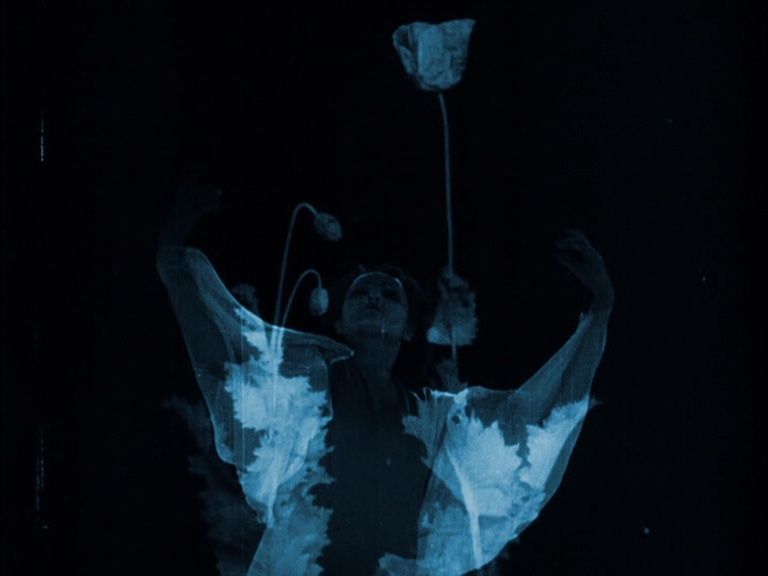

Greenish shoots from the soil. The pulse of low strings. Solo woodwinds seek out a melody, test out a rhythm. The flowers look sleepy, dopey. It takes them an age to raise their buds. Fade to black, before they quite bloom in full. A strange, solo shoot—and a dissolve to a dancer, flowing white dress, mimicking the growth of the flower. A succession of close-ups, flowers trumpeting toward the lens.

Shoots fall over the side, bud slowly, change shape a dozen times. Flowers nod together, perform collective awakenings. Another solo dance, flower dissolving to dancer, dancer to flower. It’s hypnotically beautiful. A mass of buds, flowers that slowly fill the screen, that grow stranger and more extraordinary as the shot continues. End of Part Three.

Part Four. Flowers that open and shut, that wither, that die. The life of plants, their struggle, their disintegration. Flowers with skirts, which become a troupe of dancers. The dancers are now in slow-motion, performing impossible manoeuvres on their toes, leaping as if weightless. So entranced am I that I don’t question the continuity between flowers and dancers, between stop-motion and slow-motion, between days-between-frames and microseconds-between-frames.

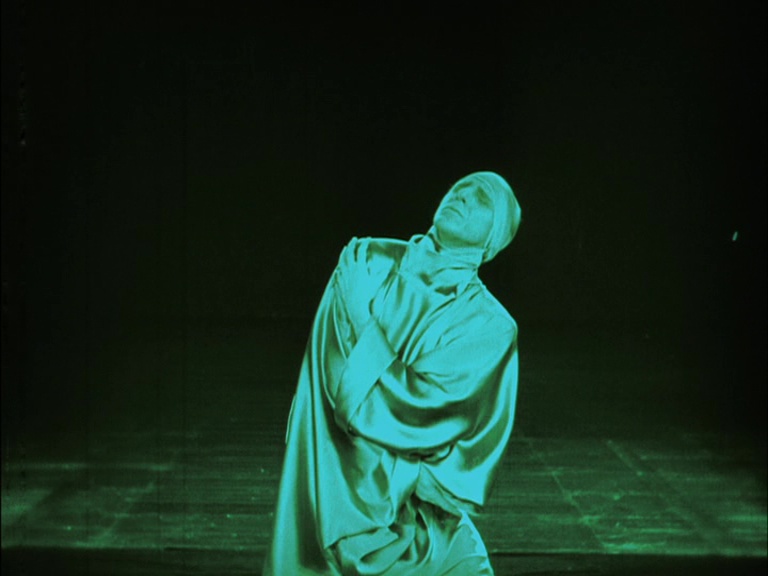

The music slows. There’s that pulse in the timpani. It’s almost funereal, that beat below the strings. The progress of leaves, of petals, of stamen. It’s agonizingly slow, this sped-up motion of the flowers. It’s a ballet created by removing days, weeks, years’ worth of time—and yet time seems to be suspended. The camera manages to track around some flowers, to capture their slowness with an even slower repositioning. Another dancer; combined with the tinting and toning (dark brown tone, turquoise tint), the sheen of his robes becomes surreally bright, surreally three-dimensional. Flowers seem to gesture, and the film cuts to a man gesturing—his movements as rapid as those of the flowers. A sunflower grows, lifts its shoulders, reveals its mane of petals. The orchestra responds. We watch the tiny ripples of its seeds. Poppies grow; a dancer wakes from sleep, reaches out her arms, shows off the veils of her sleeves; so too do the poppies, before their petals unfurl, fall, disappear. End of Part Four.

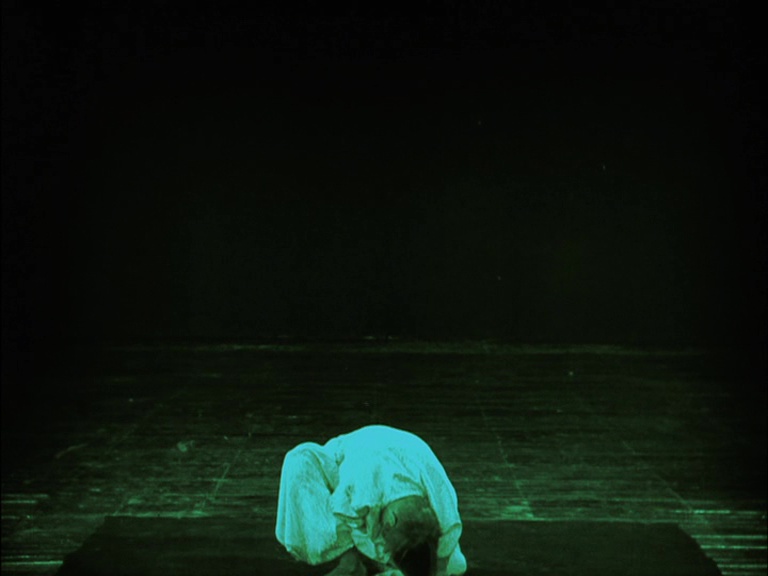

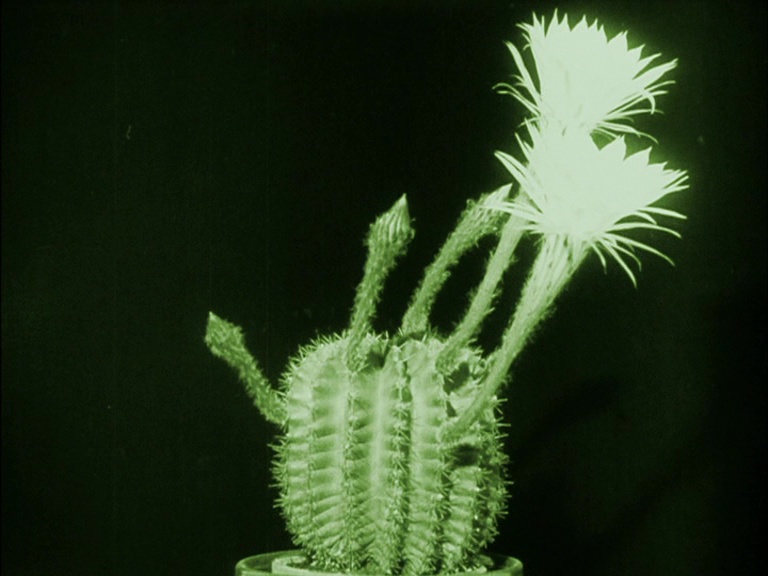

Prelude to Act Five. The music is more forceful, louder, the beat of timpani and brass spelling out some impending drama. “The song of coming-to-be and passing away.” A dancer appears, that same sheen of turquoise over the rich black-brown of the space behind them. The coming drama is spelt out in his mime: he rises, struggles, dies. The plants’ lives are spelt out in a few seconds each: they wrench themselves up from parental branches, expand to their fullest; they flinch, tremble, curl up, diminish, die. The music offers a fanfare, then a melancholy waltz, then a tender farewell. Each new plant comes before the lens, lives and fades. A multi-headed cactus performs life and death five times, each stem collapsing one after the other, each flower dying one after the other. ENDE

What a treat to discover a film by chance, and to discover it’s a little gem. I first saw mention of this film thanks to the German Wikipedia page on Eduard Künneke, which listed among his film scores Das Blumenwunder (the music for which was later rearranged into orchestral suites). I was delighted to find that a DVD was available, issued by ARTE in the wake of their restoration and broadcast of the film in the 2010s. The music was originally arranged for a smaller ensemble, but the restoration uses Künneke’s later, expanded, version for larger orchestra as its basis. It sounds lovely, full of energy, melody, and deft orchestral touches. It’s light music, but in its best sense: its transparent, generous, captivating. It works wonderfully well with the images, and by the last sections of the film—which function mostly without intertitles—the music takes up all the sense of narrative and emotive expression. As I wrote on my earlier piece on Das Weib des Pharao (1922), the music of Künneke is well worth investigating: he offers a glimpse into the soundworld of the 1920s: light, popular music, infused with elements of jazz and dance. It’s remarkable in itself that two of his scores should have survived and been recorded for issue on home media. Confusingly, both filmportal.de and the German Wikipedia page also list among Künneke’s work a film score for the German-British co-production A Knight in London / Eine Nacht in London (1928), directed by Lupu Pick. However, the two sites differ on their info for the latter film: filmportal.de claims the music was by Künneke, Wikipedia claims the composer was Giuseppe Becce. In either case, the film is unavailable to view and the score—whoever wrote it—is among the many that of the silent era that languishes in obscurity.

Das Blumenwunder was released as a kind of “culture film”, designed to attract critical attention. It certainly did, and not just from film critics. The many reviews (cited in Blankenship, 2010) focused on the revelatory way the film showed the (normally unnoticed or invisible) movement of plants. If some claimed the film belonged in the classroom and not the cinema, others were more generous. Rudolf Arnheim called the film “an uncanny discovery of a new living world in a sphere in which one had of course always admitted life existed but had never been able to see it in action.” The plants, he said, “were suddenly and visibly enrolled in the ranks of living beings. One saw that the same principles applied to everything, the same code of behaviour, the same difficulties, the same desires” (Film as Art, 136). The expressionist writer Oskar Loerke noted in his diary:

Das Blumenwunder […] was a first-class experience. Unbelievable. The film nearly proves the existence of everything supernatural. When one sees the growth and life of plants that have another tempo from that of people, every order becomes imaginable—even slower tempos or faster ones, which are not perceptible to us because of this difference. (qtd in Blankenship)

As Janelle Blankenship explains, the film did well enough to be shown on numerous other occasions by various interested organizations:

[Das] Blumenwunder was promoted by the League of Nations, screened in England at a social meeting of the Anglo-German Academic Bureau at the University of London, University College, and praised by Welsh writer and novelist Berta Ruck, among others. The film was also a ‘special sightseeing attraction’ at an ‘expo-cinema’ during the 1927 horticulture congress in Leipzig, and was screened as a horticultural film at a monthly meeting of the garden club ‘Verein zur Beförderung des Gartenbaues in den königlich preussischen Staaten, Deutsche Gartenbau-Gesellschaft’ in 1926.

Thankfully, the film was also preserved in the archives and the DVD edition presents it in excellent visual and audio quality. (Though I should add that—at least on my machine—a few of the intertitles lack the English subtitles otherwise presented throughout.) The DVD also prefaces the film with some explanatory text: we learn that Das Blumenwunder was originally 1755m (c.65 minutes) but the only copy that was preserved runs to 1664m (60 minutes). What is missing is unclear, but given it’s only a small percentage of the overall runtime we must be grateful that more wasn’t lost. The DVD includes a pdf of the original booklet issued at the premiere. Rather delightfully, the edge of each page is formed of individual frames from the film, showing you a frame-by-frame account of the growth of the flowers.

Das Blumenwunder is a visual delight, as well as a musical delight—and I’ve found myself relistening to the score three times already since watching the film for the first time at the weekend. For me, Das Blumenwunder was a real treat to discover.

Paul Cuff

References

Rudolf Arnheim, Film as Art (Berkeley: California UP, 2006).

Janelle Blankenship, “Film-Symphonie vom Leben und Sterben der Blumen”: Plant Rhythm and Time-Lapse Vision in Das Blumenwunder”, Intermédialités 16 (2010): 83–103. Available at: https://doi.org/10.7202/1001957ar