Last week, courtesy of the association Kinétraces, I had the great privilege of introducing Jean Grémillon’s first feature film at the Fondation Jérôme Seydoux-Pathé in Paris. The French text of my introduction will, hopefully, find its way into publication at some point. What follows here is different, as I want to focus on my reactions to the film itself—and on the difficulties of using digital copies to summon the fleeting memory of films seen projected on 35mm.

Maldone (1928; Fr.; Jean Grémillon)

It’s the opening shot of the film, and already a kind of revelation. On the left of frame, the line of poplars recedes into the distance. On the right, the canal curving away. In the foreground, between water and trees, the long grass, the weeds. And everywhere, the motion of the wind. It’s one of the founding stories of cinema, the way that the first audiences to see the Lumière brothers’ Le repas de bébé (1895) were more fascinated by the motion of the trees in the background of this “view” than the supposed subject of baby and parents in the foreground. And you can see why: there is something uncontrolled, something unexpected, that forces its way into our perception, that makes itself the star. The wind takes on agency, makes the trees announce its presence. It’s as though a different drama might be taking place at the back of the scene, a more expressive one; we want to crane our necks to see around the corner, to know what’s happened, what’s about to happen.

In the opening shot of Maldone, this half-hidden natural drama is allowed to occupy the whole frame. It’s just the wind in the trees, in the grass, but it’s also a rhythm of life, a sense of place and time that made my skin prickle. This was a 35mm copy, projected on a large screen. I was sat close to the screen, in the centre, and for the duration of this first shot it was my whole world. You could see every leaf, every blade of grass. The wind moved through the scene, making everything shift, turning trees and verge into a kind of kaleidoscope.

Now, a week later, I must overlay my memory of that projected image onto the equivalent image of this off-air copy—the only available copy of Maldone available to study. Even with this first shot, the paucity of the digital image—its obfuscating murk, its blocky banks of pixels—almost makes me want to stop watching the film, to fall back purely on the memory of what Maldone looked like last week. But this is a problem all film scholars (especially of silent cinema) must confront. There’s no way to study everything first-hand, in 35mm copies, projected on large screens as originally intended. And even in these conditions, we are still at a distance from the original experience of these films. Consider that the 35mm copy of Maldone we watched in Paris was itself a ghost of its former self. Maldone was one of the first French features to be shot entirely on panchromatic filmstock. All the contemporary reviews mention how stunning it looked, these opening scenes in particular. (Here is Edmond Epardaud, writing on the same date that I write this—15 March—ninety-five years ago: “The whole beginning of Maldone […] is like a visual hymn to nature. In a complete and harmonized fabric of elemental images, Grémillon notes the slow life of French canals, the flat horizons where poplars dream, the white roads whose sinuous line follows the soft undulations of the ground.” Cinéa-Ciné pour tous, 15 March 1928.) But the first nitrate positives struck from these panchromatic negatives are long gone. What we watched in March 2023 was a copy of a copy of a copy of a copy… Every time 35mm is copied it loses a fraction of its image quality. The dazzling nitrate images of 1928 are impossible to see. And as beautiful and rich and detailed as the 35mm print of Maldone was and is in 2023, I cannot but want to see beyond it, to imagine its beauty and richness and detail sharpened and intensified as it once was.

The landscapes of Maldone dominate the life of its titular character. Olivier Maldone (Charles Dullin) is a wagoner, who walks at the pace of his horses along the towpath of the canal. The 2001 restoration that is the basis of my broadcast copy has reconstructed some of the original music used at the film’s premiere. For this opening sequence, the music is by Debussy, “Nuages” from his Nocturnes suite (1892-99), and its slow, haunting, meandering mood fits the scenes well. But the film also seems to emphasize the sultriness of the score: it’s a hot day, and if we see the “clouds” of the music on screen, they are high and bright, and serve to punctuate the huge expanses of sky Grémillon shows us above the chalky roads that gleam white.

Before now, I was never wild about Charles Dullin. I had seen him in the two big productions of Raymond Bernard that sparked his own interest in producing: Le Miracle des loups (1924) and Le joueur d’échecs (1927). I’d seen both films projected on large screens (albeit via DVD), but his performances hadn’t quite stuck with me. His long face and nose, his narrow eyes, his faintly sinister gait—these did not seem to invite me into this man’s inner life on screen. But here in Maldone, on the big screen, I change my mind. He has a kind of intensity, a privacy of feeling, that makes itself felt in the way he moves, the way he glances. We first see him from behind, walking away along the path. When we are introduced to him via a title, we then see him in a close shot he shares with his horses. The way he feeds them, strokes them, smiles with them—it’s as if nothing beyond them quite matter. And his smile as they take the treat from his hand is almost a snarl. His long face and nose suddenly made a kind of sense in the scene, as if he were meant to spend his life in their company here.

But then comes the gypsy girl, Zita (Génica Athanasiou). We first see her face in close-up, over which we see superimposed two fortune-teller’s cards: La Reyne de Deniers (the Queen of Coins) and La Maison de Dieu (The Tower). It’s a slightly arcane deck being drawn, here—a mix of the Latin variety of cards (in which Coins are one suit among Swords, Cups and Batons) and a more familiar image from Tarot cards. But even in this slightly obscure imagery, Grémillon—with the slowness of the superimposed dissolves, the matching of face and pictures—makes clear their fatalistic significance. Even if we don’t know quite what they signify, we know that a kind of destiny is being invoked.

This was Athanasiou’s first film. She was a member of Dullin’s regular troupe of actors from the Théâtre de l’Atelier, which Dullin ran in Paris. But Athanasiou takes to the screen so naturally. From a dark, indefinable space, her dark eyes look straight out at us. Never mind “diegetic space”: Grémillon wants us to know her gaze directly, to feel her eyes upon us. That is what counts here. So when Maldone encounters her in the next scene, we know in advance the kind of spell that she might cast upon him.

Grémillon films this encounter at a kind of crossroads: the sluice gate, where Zita’s troupe of gypsies crosses the path of Maldone’s horses. The camera looks down on Maldone, his back turned to us. Then we see Zita, so close to the camera that her face is out of focus. We see the space before her, the canal stretching into the distance. Where is Maldone? Zita picks up a handful of dust from the ground—again, we see her from behind—and throws it out of the frame. It’s such a strange, unsettling way of filming their encounter. The spaces are clear enough, but the way Grémillon shows us the back of both characters gives a weird sense of foreboding. We can’t read their faces before what happens happens: motivation is obscured, hidden. Cut to Maldone, far below us; he turns, looks up.

Then comes a shot to make you gasp: Zita, seen from a low angle, the trees moving in the wind behind her. The trees are a blur, their solidity transformed by the lens into a kind of softened wave that looks as though it’s about to break beyond the frame. Zita is looking at us—through us, past us. She’s drawn herself up, her sleeves catching the wind. She turns to face us, places her arm seemingly to lean on the bottom of the frame (the fence below her hands is out of sight: the framing of her gesture is so perfect, it really does look like she’s about to lean out of the screen). She looks fearsome, extraordinary. It’s a shot that has stayed with me since I first saw the film, many years ago, and to see it projected from a 35mm print was another kind of revelation. It’s a fabulous image, designed to impress, to transfix.

For when we cut back to Maldone, in close-up, the smallest of twitches passes over his face. There are glints of light in his dark eyes. But he’s so still: everything that’s happening is happening inside his head. We cut back to Zita, now in a different composition, the camera more on a level with her body. She’s less unreachable. There is some secret, untranslatable communication here. She changes her posture once, twice, three, four times—shifting her back, shoulders, head, eyes. Maldone is surely lost. We are surely lost. Look at how Grémillon then frames our last glimpse of Zita, which is also her last glance at us in this scene. The way Grémillon highlights the perspective, the receding hillside, trees, road; the huge slab of sky; and Zita, smiling, glowing against the dark expanse of trees and hill. Who can resist such a film?

“You’re not twenty anymore”, says the bargeman to Maldone, as Maldone watches Zita walk away from this first encounter. It’s a neat line, and got a laugh in the screening I attended in Paris. But look at the way Grémillon follows his joke: a medium close-up of Maldone, looking slightly sullen, slightly sad. Look at how the rope he carries for his horses is wound around his neck. It’s like a noose, in place but as yet untightened. Maldone walks away. And it’s surely not the walk of a young man. There are innumerable films of this period (and beyond) where Dullin—forty-two at the time of filming in 1927—would be pretending to be twenty. It’s a mark of the film’s maturity that part of Maldone’s tragedy is to be already past his youth when the opportunity arrives to start a new life (with money and marriage), or even two new lives (with a lover and a life on the road). Maldone’s ensuing entrapment and attempts at flight are set within this acknowledgement of age and ageing.

And throughout the film, other characters are always looking on from the margins. Look at the shot that follows Maldone walking away. It’s a middle-aged woman, leaning on a wall, watching the slow, slow, passage of the barge. Grémillon fills the film with glimpses of these real people—never characters, always people. And real animals—Maldone’s horses, the dog sleeping on the barge, the chickens in the coop—that likewise take their place in this world. The pace of working life is also real. After his encounter with Zita, the film gives us a section presaged by the title “Days are all alike”. So we see the drowsy barge, the trees passing slowly overheard, and the dreamy smile of Maldone as he takes it all in. Grémillon shows us the light reflected on the water (and it truly dazzles on 35mm), then superimposed over Maldone’s face. Time is measured by these flicks of light, by the waving of the trees.

Zita and her family get by through reading fortunes and a little light theft. Maldone works by guiding his horses, who pull the barges. The drama of the film shifts in this section, as we see for the first time Maldone’s family estate, which he has long ago abandoned, together with his brother, Marcellin, and uncle, Juste. The world of this estate is a world apart. The brother and uncle are seen enjoying the space around them through leisure: Marcellin rides horses for pleasure, but Olivier Maldone walks alongside them for work. These two separate realms are intercut in through a kind of fatalistic editing. First, Zita’s mother reads Maldone’s palm. “Your enemy is inside you”, she says. “I see a man and his enemy in the same man… A vagabond, a rich man… One of them must destroy the other.” And when, in the tavern, Maldone reads Zita’s palm, Grémillon intercuts between their exchange of glances and the fate of Marcellin, who is killed while out riding.

Again, Grémillon grounds this kind of fatalism with the world around his characters. This scene takes place in a working-class tavern. We see old men and women, going about their lives. At the Maldone estate, the stable hands and the workers on the grounds are likewise non-professional actors. They people this world, make it real, whole. Later in the film, when Maldone returns to his family estate and marries Flora (Annabella) he escapes to the surrounding villages whenever he can. The pull of the open landscapes draws him away from home, but so too do the people. Maldone stands and admires the sight of a traction engine being used to help sift the grain. Grémillon shows us the workers, real workers, lifting and threshing the hay. The camerawork feels so natural it looks up at their work, peers into the barn, nestles among the grass, observes the machine, catches the faces of the men and women as they work.

This is also one of the reasons that the performance of Georges Séroff as Léonard, the old family servant, slightly grates with me. For after Marcellin dies, he is sent out to find Olivier Maldone. Léonard’s huge white whiskers, his bald head, his mouth perennially hanging open, make him a comic character whose slightly exaggerated performance is at odds with those around him. When he takes the train, he is surrounded by palpably real people, non-professional performers, the everyday users of the local train service. It’s worth remembering that Grémillon made his name in the film industry between 1923 and 1926 through the making of documentaries. Many of them focused on the ordinary lives of workers—men and women who made small livings as laborers, fishermen, seamstresses, roadbuilders, brewers, tram conductors.

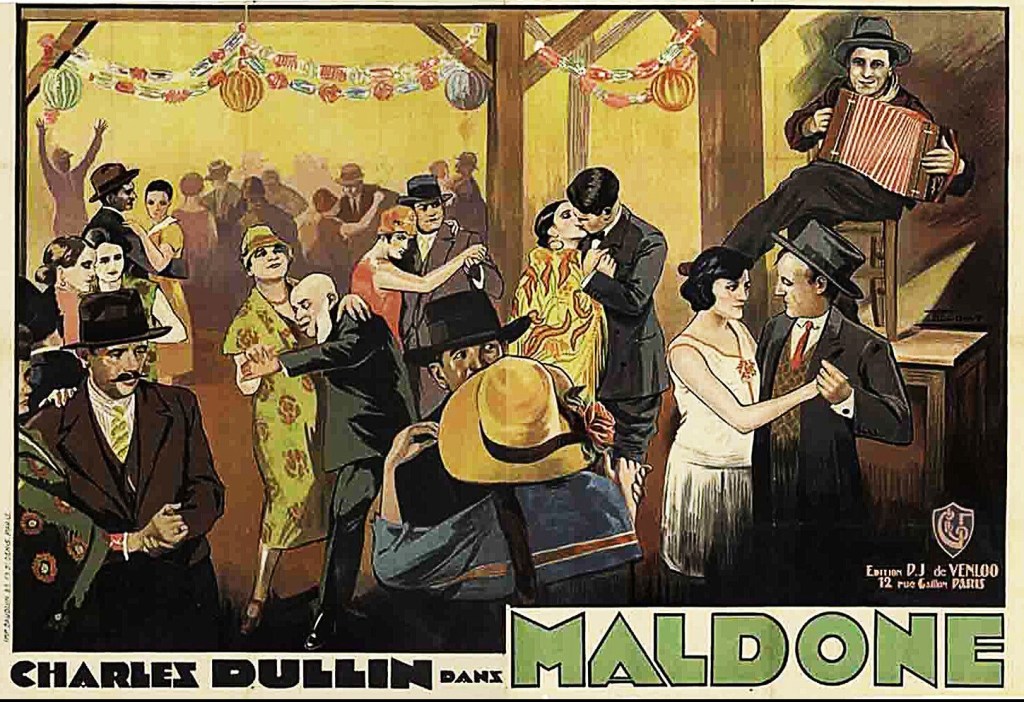

So to the dance at Saint-Jean, where Maldone takes over the accordion to play for the dancers, and Grémillon gives us one of the most extraordinary dance sequences of the silent era. The sets here (by André Barsacq, Dullin’s regular theatre designer) were constructed with four walls, and with ceiling. Every conceivable angle is exploited: shots from outside, inside, high angles, low angles; the camera is among the dancers, above the dancers; it looks down from the ceiling, up from the floor. But it all builds slowly, so that you hardly realize just how far Grémillon is about to push his expressive means. There is one dance, relatively gentle, in which the main event is Zita’s arrival, then another—in which Maldone leads the dancers in a line that leads around the entire space of the hall, upstairs, downstairs, and back again. Then Maldone flirts and half dances with Zita, before a final dance increases the tempo even further.

The melody is given us in a title: “La Belle Marinière” (valse), and then (per the instructions of the original score) by the accordion itself. A stranger dances with Zita. Maldone sees her. The cutting accelerates. Close-ups of hands, feet, of the accordion being squeezed, of the dancers swirling, of drinks, or skirts, of faces. Then Zita and her partner, seen from above, clinging together, her skirts spinning below then.

Grémillon holds this shot, and holds it, and holds it. We watch them spin, held together by a kind of gravitational force, a centripetal energy—it’s desire, it’s heat, it’s two bodies pressed against each other. It’s a shot that could go on forever, a whirlpool that spins and spins. And I could watch it forever, hypnotized. It’s a shot of extraordinary power. The lovers are giddy. Zita blinks, looks up. They kiss, and the music stops. The accordion falls from Maldone’s hands, just as (in the theatre) the musician in the orchestra must drop his instrument. Maldone chucks a drink into his rival’s face, and Grémillon captures this in handheld shots that quiver with fury, just as the fight is a dazzling eruption of quick-cutting and frenzied whips and pans of the camera. The screen pulses with anger, the camera lurching back and forth along the axes of the fight; it’s in the belligerents’ faces, feeling their anger, reeling with their punches; it’s in the eager crowd, jostling, dodging, pressing close. The stranger is ejected. The crowd hails Maldone.

In the early hours, Maldone and Zita are alone in the deserted tavern. But Léonard stumbles in and recognizes Olivier Maldone as the man he seeks. He shows him a photo of the young Olivier Maldone. Maldone gazes at Maldone. It’s the first time we see a kind of double for this man, this man whose fate we know is to have his enemy within him. Zita edges away. A close-up of her hand in Maldone’s, slipping slowly from his grasp. The men get closer. Léonard weeps. Maldone weeps with him.

Three years pass (and the suddenness of the transition, the knowledge of time passed, is a kind of shock). Maldone has married Flora (Annabella). This was Annabella’s second film, having been launched into a kind of stardom by her role as Violine in Gance’s Napoléon the year before (1927). She spends much of that film being sad and wistful, and in Maldone she spends all her time looking sad and wistful. (If you want to see her being given the chance for a wider, even wilder, range of emotions, you should seek out Pál Fejös’ Tavaszi Zápor (1932), a film of surpassing strangeness where she gets to live an entire life of hope, misery, squalor, prostitution, holy fury—before dying and ascending to heaven, only to find a way of saving her illegitimate daughter back on earth. It’s really quite something, and shows what Annabella could do when given a film centred entirely on her emotional life.) For her ability to be beautiful and neglected and sad, Annabella is well cast in Maldone, I suppose—but I do pity her for being so pitiable, and wonder what more she might have done.

In these scenes on the estate, Grémillon lets the film grow sluggish. Married life is monotonous for Maldone. He looks awkward in his expensive suit. He moves stiffly. He has his hands behind his back. Flora’s father, M. Lévigné (Roger Karl), reads the paper. Maldone stares idly at his family. His uncle Juste (André Bacqué) is a lepidopterist. He examines butterflies under with a lens, and Grémillon’s camera looks down on him from behind, another lens superimposed in close-up: Juste becomes a specimen for our attention. But all Maldone’s “family” are seen in close-ups in the same way, from behind, the camera looking over their shoulder. They are made into strangers by the way Grémillon frames them, denies us their faces.

It’s a relief to get outside, to see Maldone on horseback. But he’s took well dressed, still suited, gloved, cravated. His uncle is catching butterflies. Juste shows Maldone his latest catch in a jar. While Juste looks away, Maldone removes the lid, taps the glass, watches the butterfly escape, reseals the jar, and hands it back to Juste. It’s a lovely scene and got another good laugh in the screening I attended. And when Maldone laughs in the next shot, it’s a roar—his body rocking against an open sky. Juste asks him why he must make Flora so unhappy. Why not travel, soothe his restlessness?

Maldone is in a hotel lobby. Zita walks by. Maldone follows. Flora is upstairs, alone. Grémillon distils all her loneliness into two shots. We see Flora on the threshold of the room. The threshold is light, the room is dark. Flora stands silhouetted on the left of the frame, staring into the dark. A close-up of the floor: dim swathes of light, refracted through patterned lace curtains, move across the carpet. Vehicles must be passing outside. It’s a simple shot, but everything about it carries emotional and expressive weight. Each beam of light that crosses the floor marks the passing of time, as well as giving a sense of other lives being lived—outside the room. Even the luxury of the room makes it sadder: for the ornate curtains make the light entering the room drearier and the outside world more obscure. The mere act of isolating this detail—of taking the trouble to look at it at all—is a kind of sadness, of desperation. For surely it’s Flora who looks, who sees the light passing over the floor of her room, whose subjectivity we are invited to share with this shot. You stare at the floor when you’ve nothing better to do, when you’ve no-one to share your unfilled hours. It’s an image of transience, but an image of boredom. It’s a hotel room in a nameless town. Flora goes over and stands next to the curtains. She doesn’t open them or look beyond them. She just stands there.

Maldone and Zita enter a dancehall. A jazz band plays. A trio dance. Flora sits in her empty room, as the orchestra belts out the jazzy, fortissimo polytonalism of Millhaud’s La création du monde (1922-23). But for the next scene, the lyrical section of this same piece gives the old lovers’ time together a dreamy, sensuous dimension. Watch how Maldone presses his face against Zita’s arm. On a large screen, you can really see how he’s inhaling the scent from the pit of her arm—he drags his nose across her skin. He takes her hand. Grémillon cuts to a strange vision of Zita, superimposed over the fronds of a plant. She’s as out of reach here as she was in the first close-ups given her in the film. Maldone senses this too, and presses her close. He sees another image from his past: the slowness of the barge moving along the canal. (Time passes before him: between each flashback a waiter has come and brought the next course. A huge lobster is replaced with a great platter of fruit.) But a man is eyeing Zita from across the room, and there is another flashback to the dance and the fight in the tavern. Maldone’s two lives are meeting, colliding. Zita leaves. It was nice revisiting her past, she tells him, but she has another life now. The dancers fill the space. The screen overlays them, multiplies their presence, showers them with streamers. Five in the morning: Maldone is alone on the dancefloor. The floor is covered in piles of streamers. They resemble the piles of cut hay we saw being threshed earlier in the film: the urban dancefloor parodies the rural farm. Maldone returns to Flora. They weep together.

On their return trip in the carriage, visions assail Maldone. Past and present are quite literally combined: over images of Maldone and Zita earlier in the film, Grémillon superimposes the flashing light and shade of the roadside trees. The cutting accelerates. We see the old Maldone, whipping his horses into a fury. The horses appear to double, split. As foretold, there are two Maldones, two lives in one man. But just as the rhythm of cutting grows frenzied—shots of the road, of trees, of the horses’ legs, of the spinning wheels, of Flora’s nervous face—Maldone comes to his senses.

But back on the estate, he cannot escape “his obsession”. Everything reminds him of the past: the labourers, the fields, the wind in the trees. “Each night, the prison of contentment closes in on him…” Look at Maldone, hunched at the family dining table. Flora is knitting a baby’s tunic. Look at the way Grémillon makes everything awkward: the massive lamp placed between the married couple, the way all gestures are made over people’s shoulders, the way the only light and warmth in the scene is at the table, the last place Maldone wants to be. Flora puts her arms over his shoulders. He throws them off, marches out.

He rides up the hillside. We see the valley, far below, and the mountains beyond. Seen on 35mm, this is truly a vision to inspire travel. (God, how disappointing to be watching this broadcast copy again, and not to be able to relive that desire to run down that hillside on screen.) This is where he should be, surely. So he ignores Flora, argues with her father, and plans to leave.

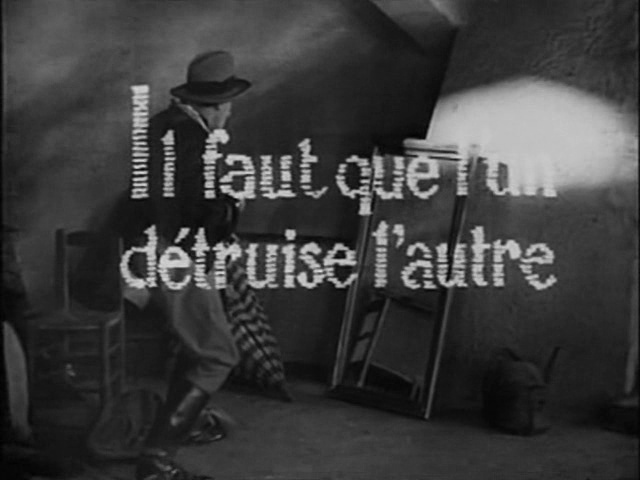

He writes his letter—almost a suicide note, a suicide of one half of himself—on a desk strewn with his uncle’s butterfly cases. He himself has become a kind of well-dressed creature, pinned to the estate. He runs upstairs to a loft. In the mirror is his new life, well dressed. In the mirror is his old life, the scruffy wagoner. Grémillon’s camera finds interesting ways of viewing Maldone in these scenes: again, the uncomfortable looks over the shoulder, or the camera perched above him, looking down from the very roof of the loft as he changes into his old clothes. Thus we observe Maldone splitting, transforming, regressing. The text of his fate is superimposed over the image: “one must kill the other”. This text—the only text to appear outside the confines of an intertitle, within the world of the film—is a kind of indelible stamp, as fatalistic a visual signature as any in the film. As if obeying its command, Maldone gets out a gun and shoots the mirror. The glass shatters, but the broken image is of his old self: continuity has been abandoned, for Maldone is already in the clothes of his former life. It’s a weird, unsettling scene. I think back to Der Student von Prag (1913), and the price the student must pay for killing his double. What is Maldone’s price for this act of symbolic murder?

Maldone is riding so fast the camera can barely keep up with him, as it tracks at breakneck speed through the meadows, the dark wall of trees looming behind the rider. An image of a whirlpool, upside-down, spills onto the screen. The camera flees before Maldone. He rides on, and on. The camera tracks, then pans, uncertainly, seeking a new direction, as if it might fall, or the world fall before it. Maldone’s face, not triumphant, but astonished, almost fearful. The image of his horse’s pounding legs and flanks, superimposed over the tree-lined canal. But it’s not the canal, it’s a reflection of the canal, upside-down and inverted by the camera; it’s the water of the canal. It’s another mirror, another doubling. And it’s an image of stillness beneath the image of the galloping horse. The image of the horse fades away, leaving nothing but the reflection of the canal. FIN.

Watching this film on 35mm was a treat, even if (as we were warned by an introductory title) the print contains elements that are beyond restoration. There were some interesting curiosities about “end of part two” etc. midway through several intertitles, suggesting a rather complex history of structure and reel-based changes. Maldone, after all, has a complex textual history…

At its premiere in February 1928, the length of Maldone was 3800m: about 165 minutes long, when projected at 20fps. It was then reduced by its distributor—supposedly with the guidance of the film’s producer (Dullin himself), screenwriter (Alexandre Arnoux), and Grémillon—before receiving a general release in France in October 1928. But what survives now is a version of 1857m, a little over 80 minutes of screen time—i.e. less than half the film Grémillon originally assembled. The film was very well received in 1928, but the premiere version was criticized for its excessive length. According to one reviewer, it was “a pure masterpiece compromised by clumsy editing and insufferable longueurs”(Cinéa-Ciné pour tous, 1 June 1928). It’s impossible to know, now, how much of significance was cut in the summer of 1928 and how much more has been lost since then.

I can understand why the film was cut, as even some of the surviving scenes on the estate feel (deliberately and purposefully) slow. And the number of flashbacks that occur in the surviving film feels too much: they clearly belong to a longer version of the film, where the flashbacks are as much for the audience’s benefit as for the characters. (Across 165 minutes, flashbacks are a useful way of singling out certain scenes from the wealth of narrative. Across 80 minutes, they feel like we have a short attention span.) Likewise, the reconstructed music for the 2001 restoration often works well but feels a bit uneven. Grémillon and his musical collaborators (Marcel Delannoy and Jacques Bridouin) surely planned the choice of compositions carefully and arranged them according to the montage of the film in February 1928. How well can you hope to synchronize music with a film missing over half its visual material? At the Paris screening last week, Maldone was accompanied by an excellent improvised piano score by Satsuki Hoshino. There is some benefit in an improvised score for such a fragmented print: the music can react to what is there, rather than struggle to adapt to what is not there.

But the amount of missing material surely highlights just how much feeling, how much meaning, Grémillon packs into every shot—and on watching it again, I could easily imagine cutting what remains even further, to make something slightly tighter and more coherent. You could see the whole dramatic interchange of Maldone, Zita, and Flora, in a handful of scenes, gestures, glances. There are shots in this film—the landscapes, the close-ups of Zita, the spinning dancers, the parting of hands, the galloping horse—that encapsulate the whole film, that stay with you long after it has ended.

What else can I say? The gulf between the broadcast version I knew and the 35mm copy from the CNC we saw at the Fondation Jérôme Seydoux-Pathé was vast. I loved the film more, was more moved, more transfixed, more impressed by everything in it. It’s a strange, uneven, bewitching film. Even as a fragment of its original self, Maldone is beautiful enough.

Paul Cuff