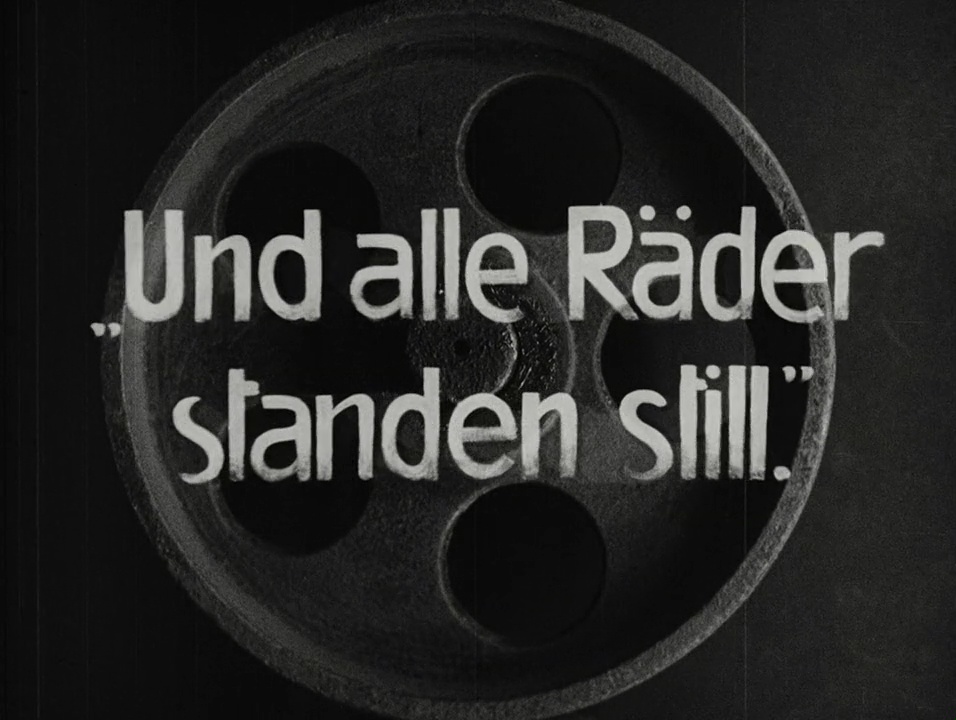

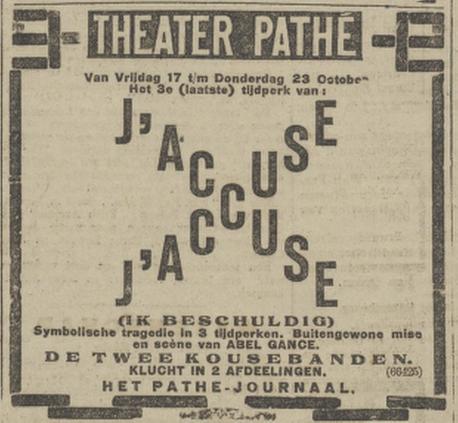

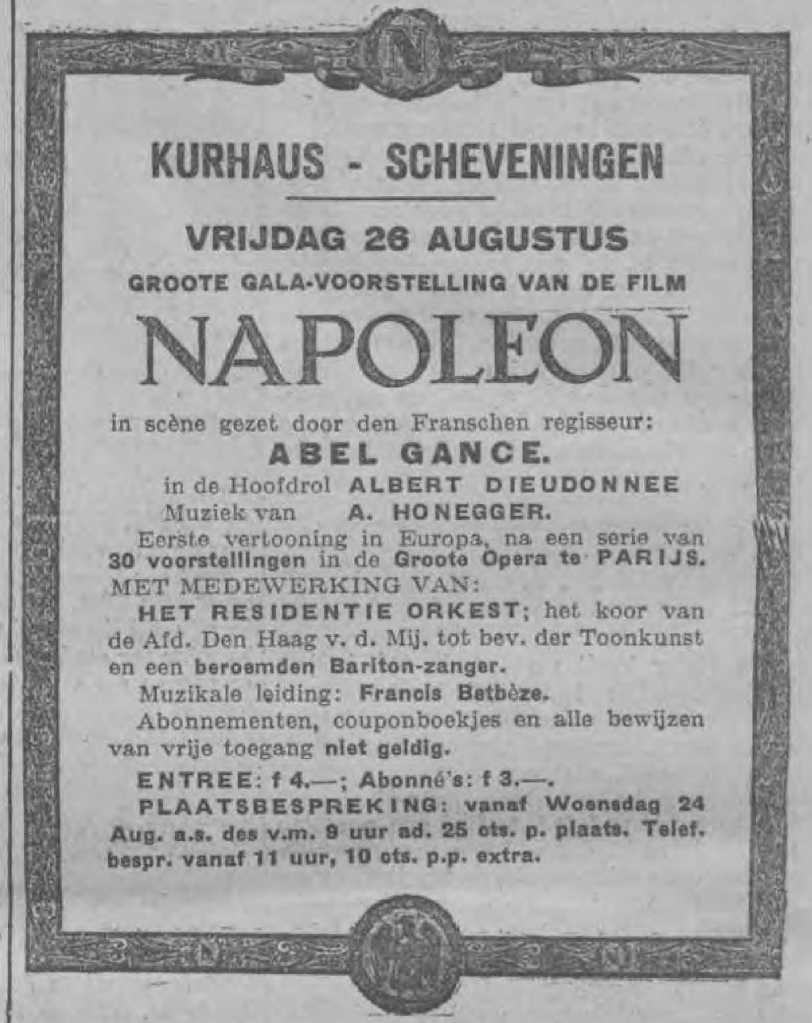

In 1928, Marcel L’Herbier undertook the most expensive film of his career. His adaptation of Zola’s novel L’Argent (1891) transposed the action to contemporary Paris. As well as shooting in the real stock exchange of the Paris Bourse and on the streets of Paris, L’Herbier had a series of fabulously large and expensive studio sets designed by André Barsacq and Lazare Meerson, constructed at Joinville studios. His chief cameraman was Jules Kruger, who had recently led the shooting of Abel Gance’s Napoléon (1927). Seeing the astonishing range of mobile camerawork in the latter, L’Herbier wanted to take advantage of every possible visual means of capturing the febrile atmosphere of the financial market and the machinations of his fictional protagonists. All this came at a huge financial cost to the production. L’Herbier allied his company with Jean Sapène’s Société des Cinéromans and the German company Ufa in order to guarantee his costs, cast foreign stars, and achieve European distribution. He spent the huge sum of 5,000,000F, much more than intended. (Though, for context, Gance spent 12,000,000F on Napoléon.) When the film premiered, it was around 200 minutes long. It was cut for general release to less than 170, and what survives in the current restoration is a little less than 150 minutes. Thankfully, what does survive is in superb quality—and the Lobster Blu-ray released in 2019 presents the film in an excellent edition…

The title of my piece this week is “rewatching L’Argent” because I do not intend a detailed review of the film. For a start, it’s too long—too complex, too interesting for me to do real justice to. (I know that if I tried, I’d end up writing more than anyone would want to read.) Instead, my reflections are inspired by being able to watch this film in a different context to that in which I first saw it. That was at least fifteen years ago, at the NFT in London. I saw the film projected from a superb 35mm print. The music was a live piano accompaniment. There were no subtitles, so instead someone in the projection booth read translations over the intercom. I won’t deny that this was a hard task to do convincingly, and that the person doing it failed utterly in this endeavour. It sounded like a playschool performance, only executed by an adult. If you’re going to present a film this way, either read the lines utterly without emotion or emphasis, or get someone who can actually emote. (I long to have experienced a live performance of L’Herbier’s L’Homme du large (1920) that took place at the HippFest festival in 2022, for which Paul McGann read live narration. The titles for that film are long and visually elaborate. You need to see them in the original French designs, so having an acoustic layer to the experience—one performed by a professional actor—must have been wonderful.) The screening at the NFT was someone trying to read the lines with emotion and emphasis but who had no experience as a voice performer. It was terrible. It lasted for two-and-a-half-hours.

The music

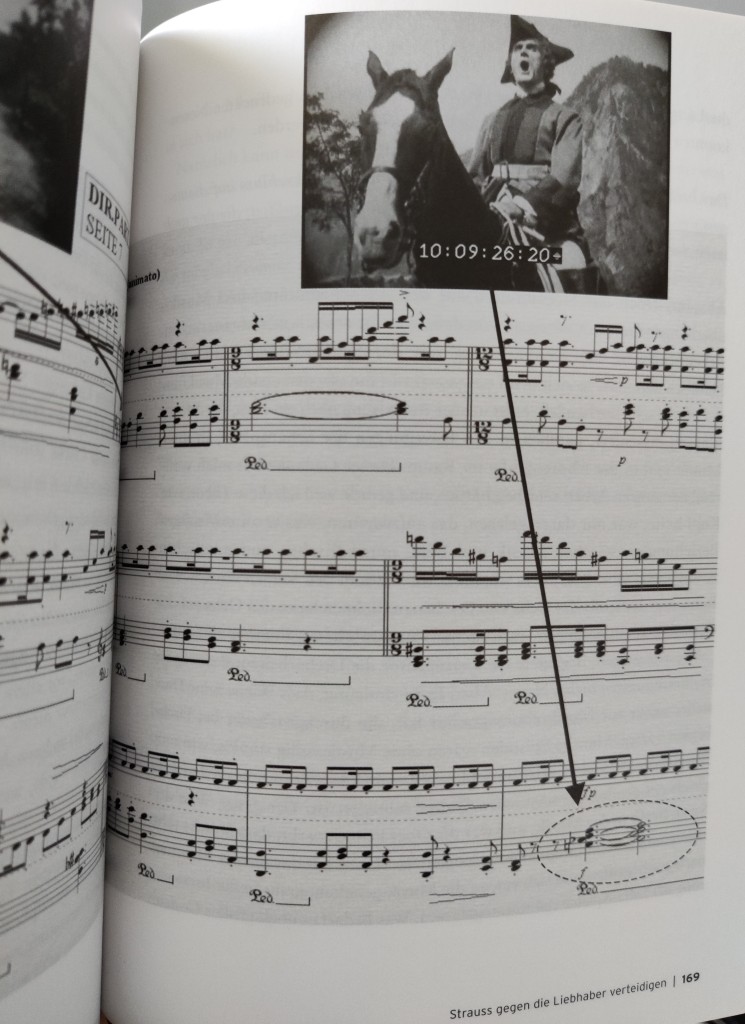

So where better to start with my experience in 2023 than with the music? As I said at the outset, my memory of this film is with a piano accompaniment at the NFT. Inevitably, I remember nothing of the musical accompaniment. (And frankly I wish I remember less about the awful translation accompaniment.) The music for the new restoration is by Olivier Massot, recorded live at a screening of the film in Lyon in 2019.

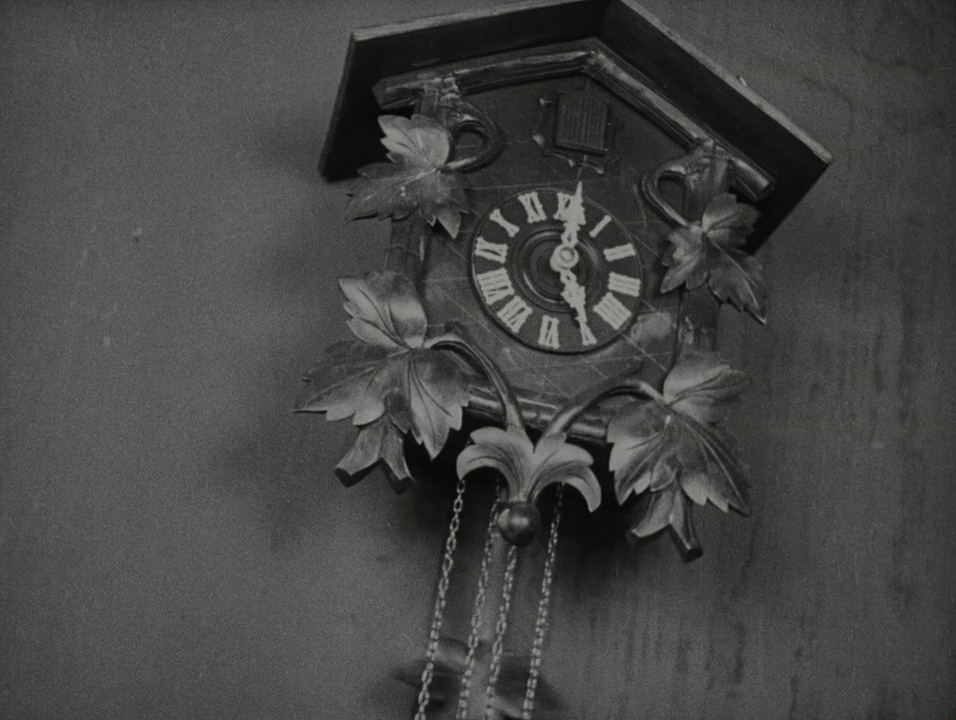

The score is for a symphony orchestra, including a prominent part for piano and various kinds of percussion. The orchestration is deliciously lithe and alert. The orchestra shimmers, shifts, glistens, growls, thunders. The writing is more chromatic than melodic: there are very few recognizable themes, as such, but the textures of the orchestra—particular instruments (harp, bassoon, tubular bells), particular combinations (high tremolo strings, descending piano scales)—recur through the film. Large church-like bells sound out at climactic moments, while the reverberative tubular bells give a cool, intimate sheen to smaller scenes. Indeed, the percussive element create some fabulous effects through the film. I particularly love the combination of piano and percussion to evoke the tolling of a clock near the start of the film, when Saccard faces ruin. Massot has bells in his orchestra, but here he chooses to mimic their sound indirectly. It’s a wonderfully sinister, almost hallucinatory acoustic: it sounds like bells tolling, but it’s something more than that—the grim dies irae melody is a kind of inner soundscape. I also love how the music is often brought to an abrupt halt for the ringing of a smaller (real) bell: at the first meeting of the bank’s council, and later with the ringing of various telephones. It really makes film and score interact in direct instances, as well as the constant ebb and flow of music and image. Then there are occasional lines for a muted trumpet that hint at the popular soundworld of the 1920s, while there is a jazz-like pulse to the grand soiree scenes near the end of the film, and woodblock percussion that characterizes the scenes set in Guiana. Throughout, the piano provides a kind of textural through-line: it dances and reacts to the film, and also to the orchestra. It’s never quite a solo part with accompaniment, but forms a part of the complex tapestry of sound that the orchestra produces. I do love hearing a piano used this way, and Massot has a fine ear for balance.

In this recorded performance, the Orchestre National de Lyon is conducted by the highly experienced Timothy Brock, and it’s a committed performance, very well synchronized. (One wonders how much, if any, work was needed to rejig the soundtrack for the subsequent home media format.) But like all silent film scores recorded live, it suffers from the weird acoustical effects of coughing, murmuring, and various other extraneous sounds of shuffling, shifting, dropping etc. As I have written before, this remains a very strange way of watching a film at home. The noises are familiar from a live screening, but on Blu-ray it’s a little surreal: you can hear an audience that you cannot see. And while I’m sure the film performance in 2019 ended with rousing applause, the soundtrack on the Blu-ray fades swiftly to complete silence. That said, you do get used to the extraneous sounds as the soundtrack goes on—but it’s an oddity nevertheless.

The Blu-ray edition also includes an alternate score compiled by Rodney Sauer and performed by the Mont Alto Orchestra. Per my usually comments (and with all due awareness of my innate musical snobbery), this “orchestral” score is banal and entirely inadequate for the intensity, scale, rhythm, and energy of L’Argent. Switch between audio tracks at any point in the film and listen to the difference in tone, depth and complexity of sound, and musical imagination. The Massot score has the benefit of a full orchestra performing a score that is alive to nuance, that is constantly evolving, shifting, changing gear; the Sauer score is pedestrian, humdrum, lagging infinitely behind the images.

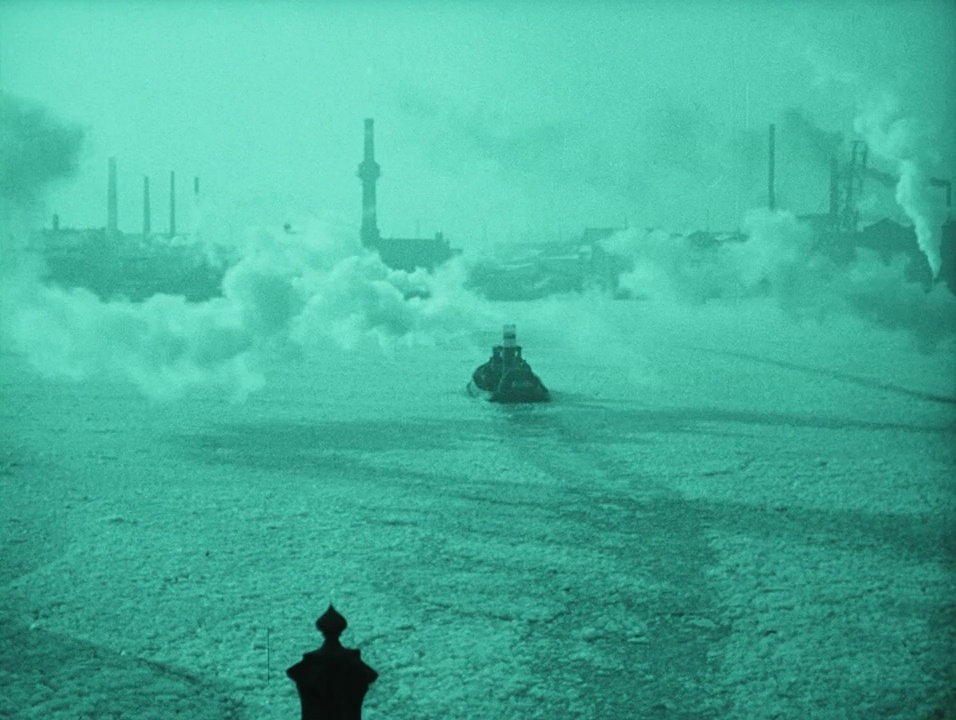

The camerawork

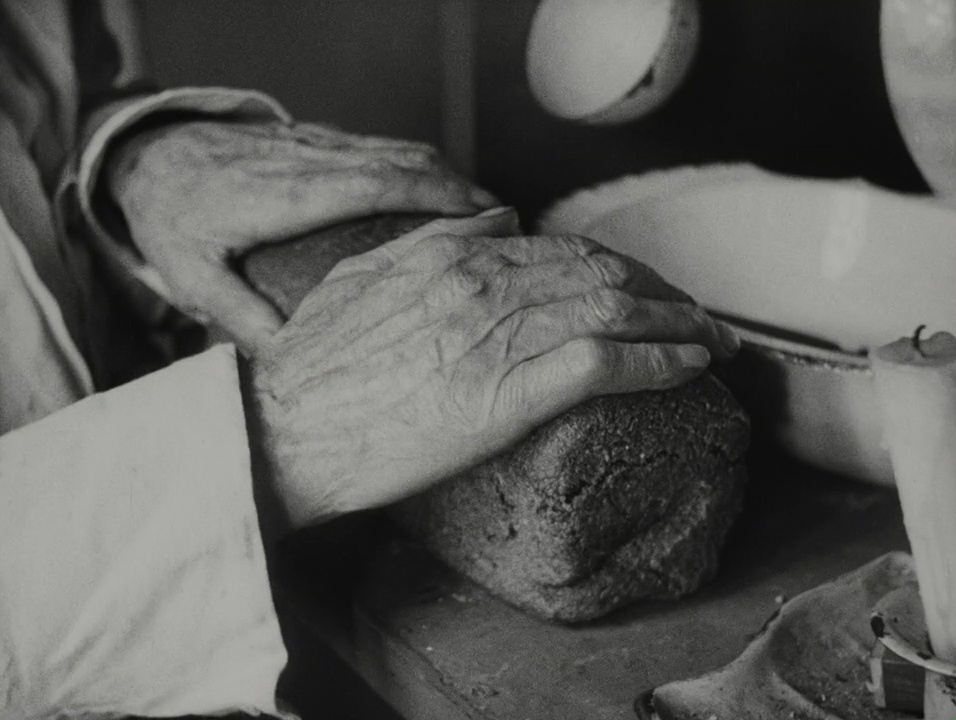

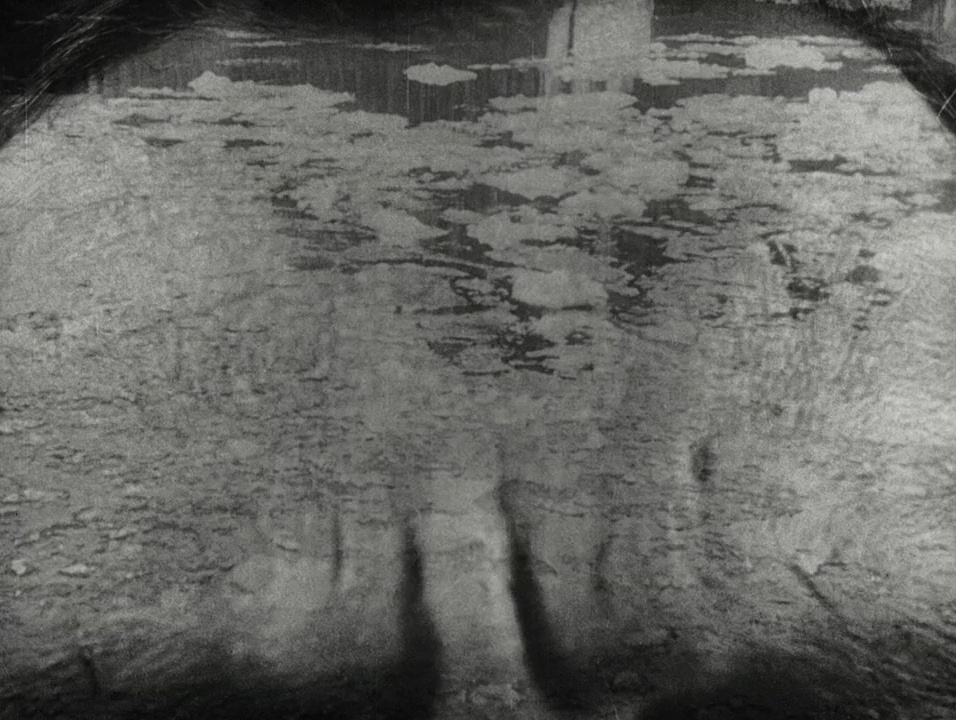

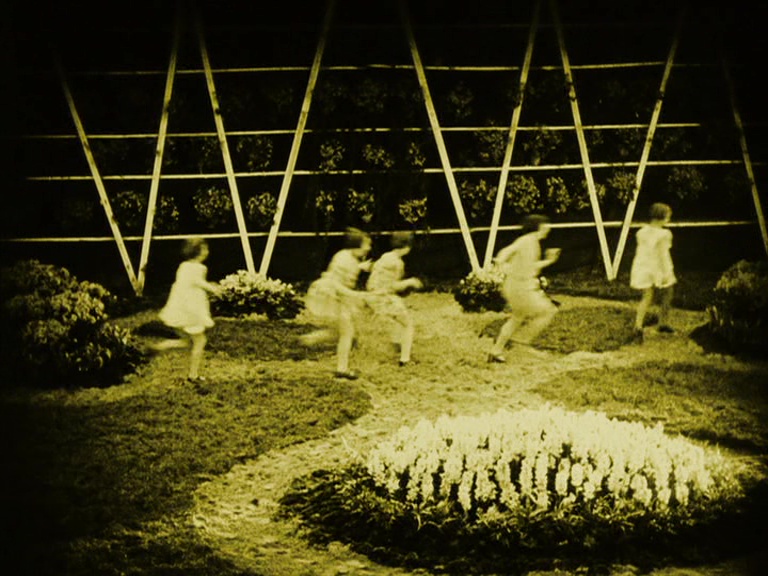

And what images they are! I’d forgotten just how extraordinarily restive the camerawork is in this film. You’re constantly surprised by the way the perspective shifts, leaps, realigns. There is a constant sense of movement in the camera and the cutting. Sometimes there are rapid tracking sots, vertiginous shifts up or down through crowded spaces; at other times there are sudden, short moves: intimate scenes are suddenly recomposed, reframed, redrawn. Kruger’s camera is often on the prowl, waiting to pounce on characters. Suddenly it was spring to life and track forward from a long- to a medium-shot. The focus warps and shifts from scene to scene. One minute the lens is squishing the extremities into blurry outlines, the next everything is crystal clear. The camera is mechanically smooth, then handheld. The lines are straight, then deformed by a close-up lens. It’s wonderfully difficult to unpick the variety of devices used across just one sequence, let alone the film.

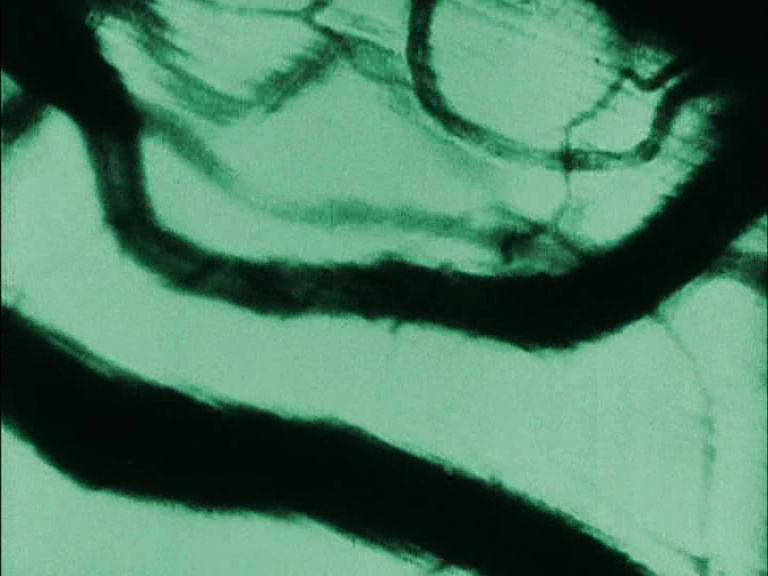

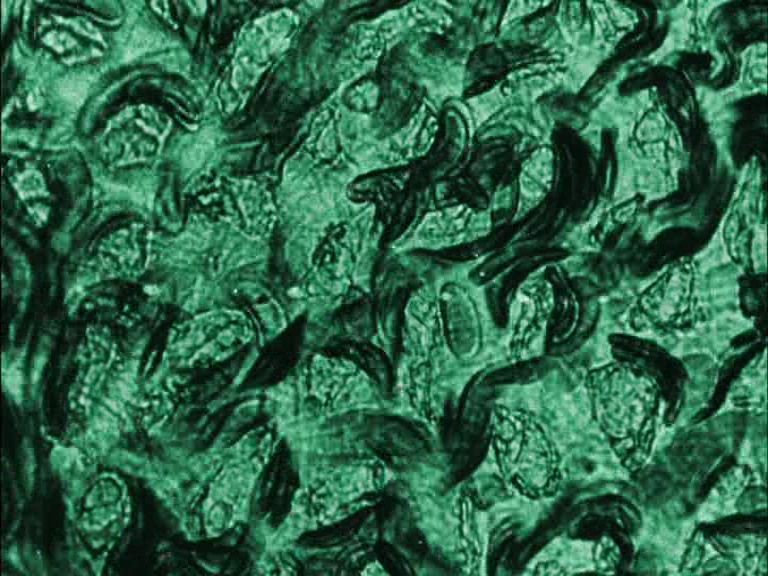

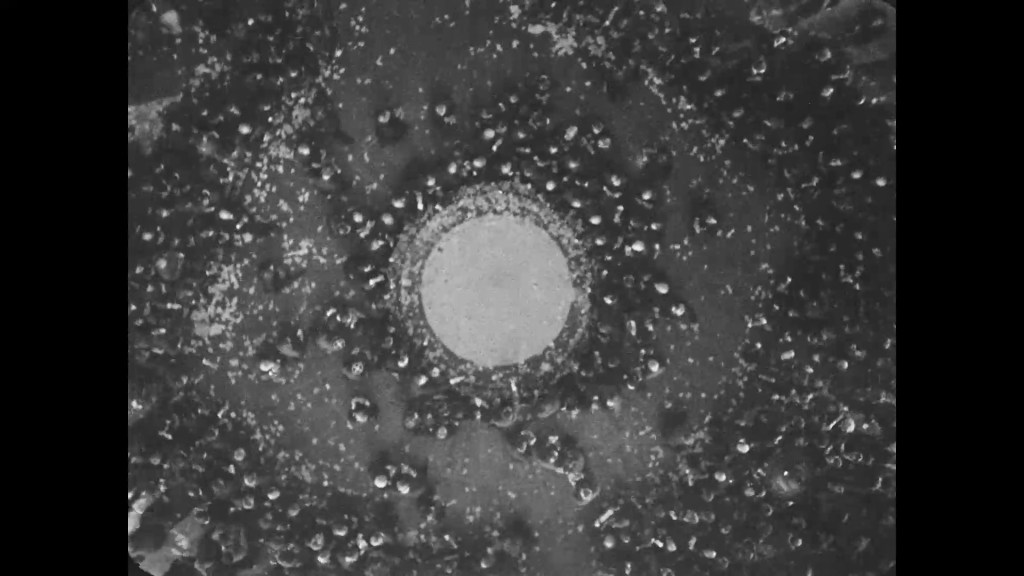

In the Bourse itself, the scale of the film—the crowds, the energy, the technological trappings—are at their most impressive. This is a real space made surreal by the way it’s shot. The camera spins upwards to the apex of the ceiling, then looks down from on high, making the crowd of financiers look like microbes swirling in a petri dish. Elsewhere, the camera is suddenly looking down from high angles, or else craning upwards from floor level. It’s an omnipresent viewpoint, operating from anywhere and everywhere.

I was also particularly truck by the nighttime scenes staged in the Place de l’Opéra. The fact that these scenes were shot at night is extraordinary, and that they look so dynamic and alive with energy is dazzling. (There is one rapid tracking shot through the crowd, lights gleaming in the far distance, that looks like it’s from a film made thirty years later.)

Throughout, L’Herbier’s cutting is dynamic to the point of being confusing. He almost has too many angles, too many perspectives, to juggle. He not only cuts from multiple angles within the same scene but intercuts entirely separate spaces. The dynamics between the various financial parties and their dealings are illustrated by cutting between these spaces. It saves on unnecessary intertitles, though at the risk of confusing the spectator. (I must say that I understand almost nothing about the financial aspect of the plot. At a certain point, references to bonds, shares, stocks, markets, exchanges, currencies etc just washes over my head. I’d be curious to know from someone who understood such things how coherent the film is in terms of its economic plotting.) There are even sporadic moments of rapid montage (per Gance) but this is never developed or made into an end in itself. Undoubtedly influenced by Napoléon, I think L’Herbier was right not to go “full Gance” and pointlessly mimic the montage of that film, which is used to very different effect (and in very different context) than this drama. L’Argent has a strange, compelling energy all of its own.

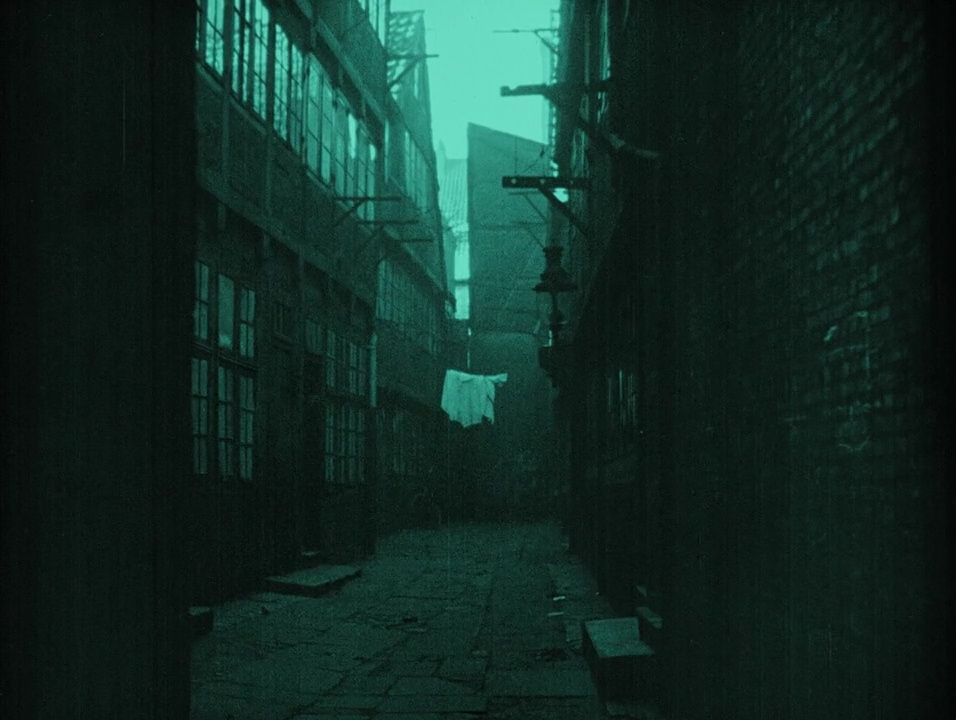

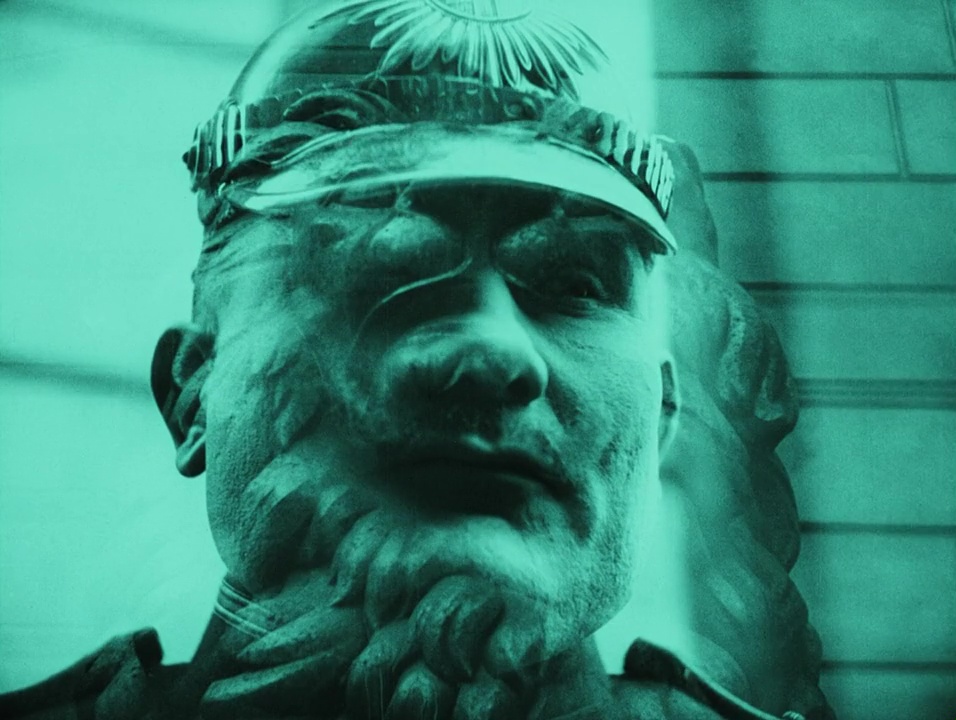

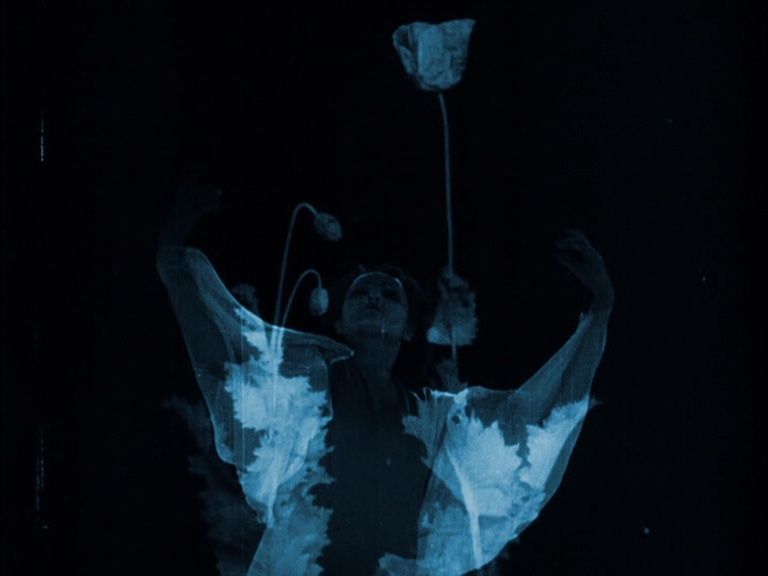

The sets

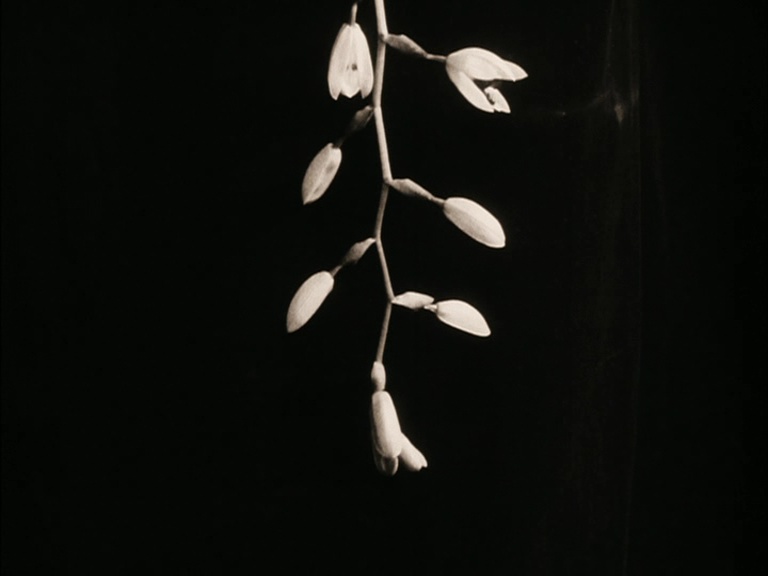

The design of this film is always eye-catching. From the massive scale of the party scene near the end (huge dance floor, cubist ponds, a wall entirely occupied by organ pipes) to the offices of Saccard that are sometimes cavernous and other times crowded. There are billowing curtains, diaphanous curtains, glimmering curtains. Light plays about shining surfaces or creates swirling shadows. Whole walls are maps of the world, doors opening and closing inside hallucinatory cells. The sets and lighting combine to make every space strange, arresting, interesting.

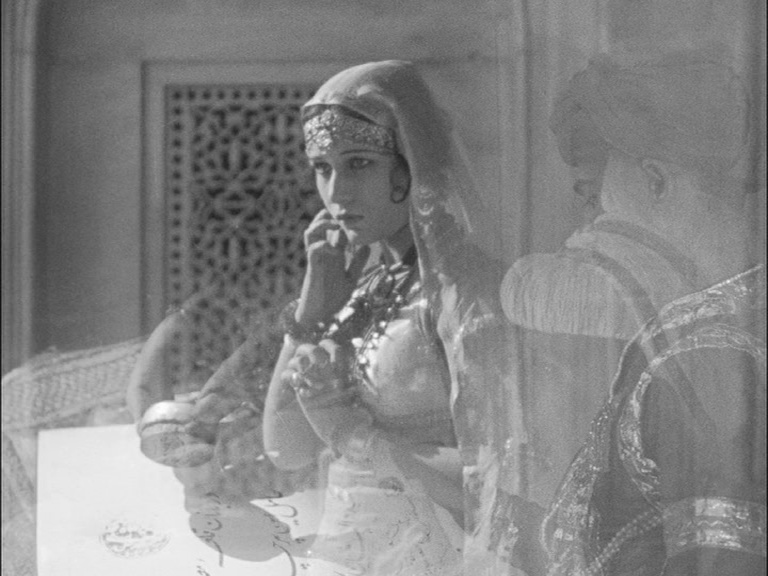

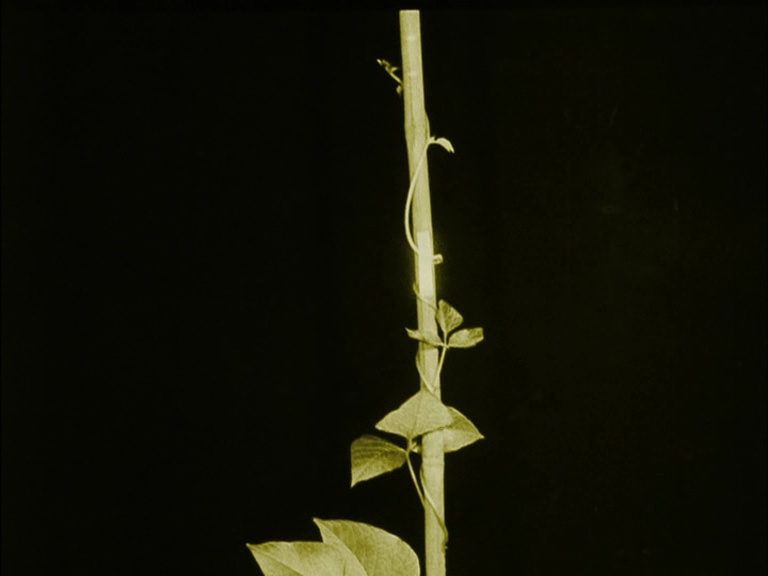

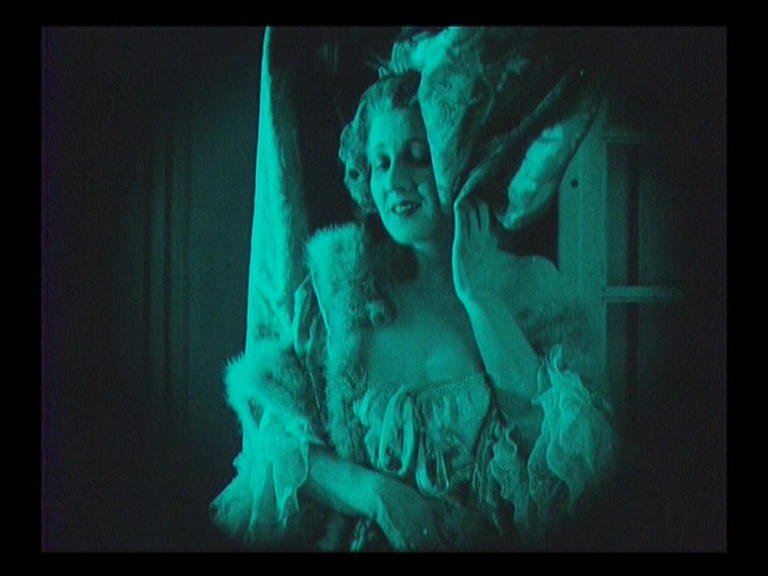

I’d also single out Baroness Sandorf’s lair, which is like something out of a Bond film. A card table is lit from within so that the shadows of hands cand cards are projected on the ceiling. The walls of one part of the room contain the backlit silhouettes of fish swimming in a aquarium. My word, the set designers had fun here. It’s just the kind of space you’d want to find Brigitte Helm in, holding court. It’s chic, cold, absurd, captivating.

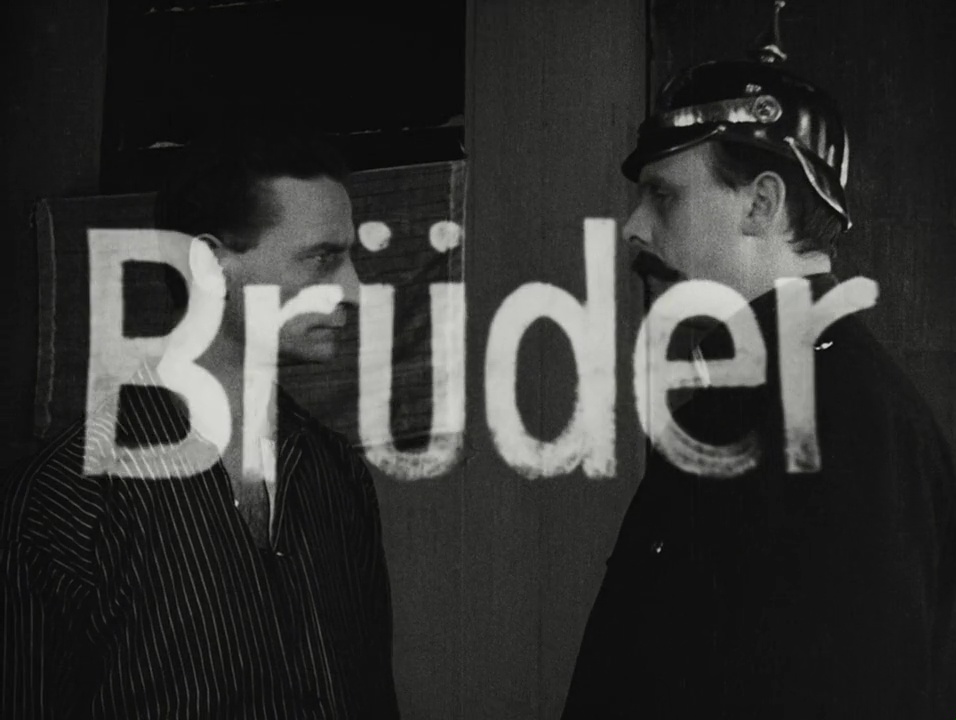

The cast

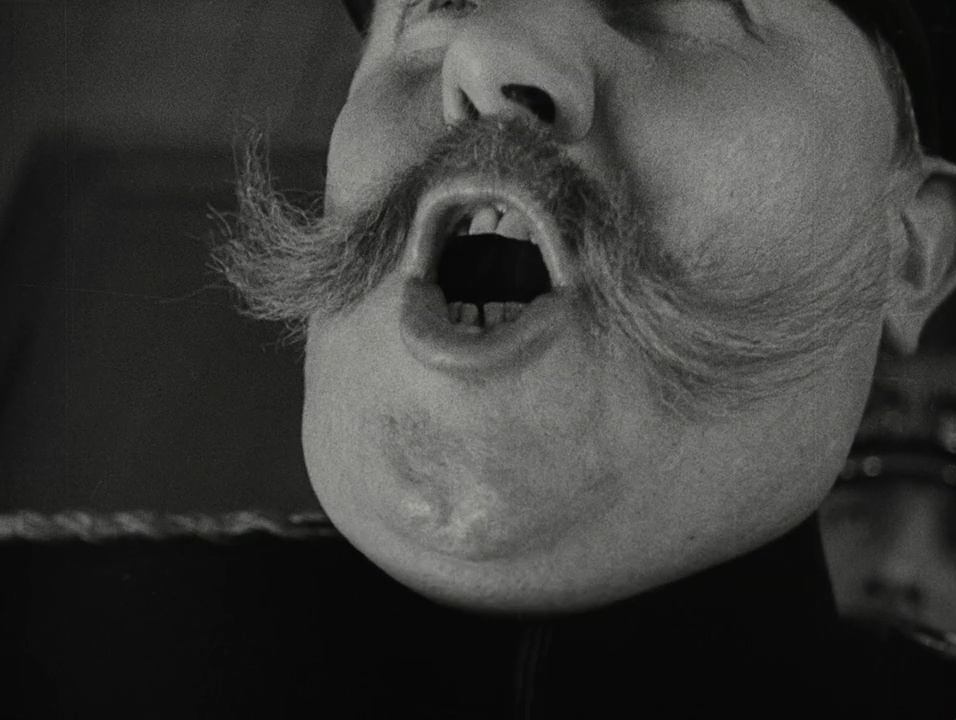

The film wouldn’t work at all if it weren’t for Pierre Alcover’s performance as Saccard. His is a superb, domineering presence on screen. His physical bulk gives him real heft, but it’s the way he holds himself and moves that makes him imposing: he can dominate a room, a scene, a shot. He’s smarmy when he needs to be, but can just as easily become threatening, scheming, brooding, energetic, resigned. He can bustle and rush just as well as he can mooch and shuffle and slouch. Strange to say, I don’t think I’ve seen him in another film. (The only other silent I have with him in is André Antoine’s L’Hirondelle et la Mésange (1920), which I have yet to sit down and actually watch.)

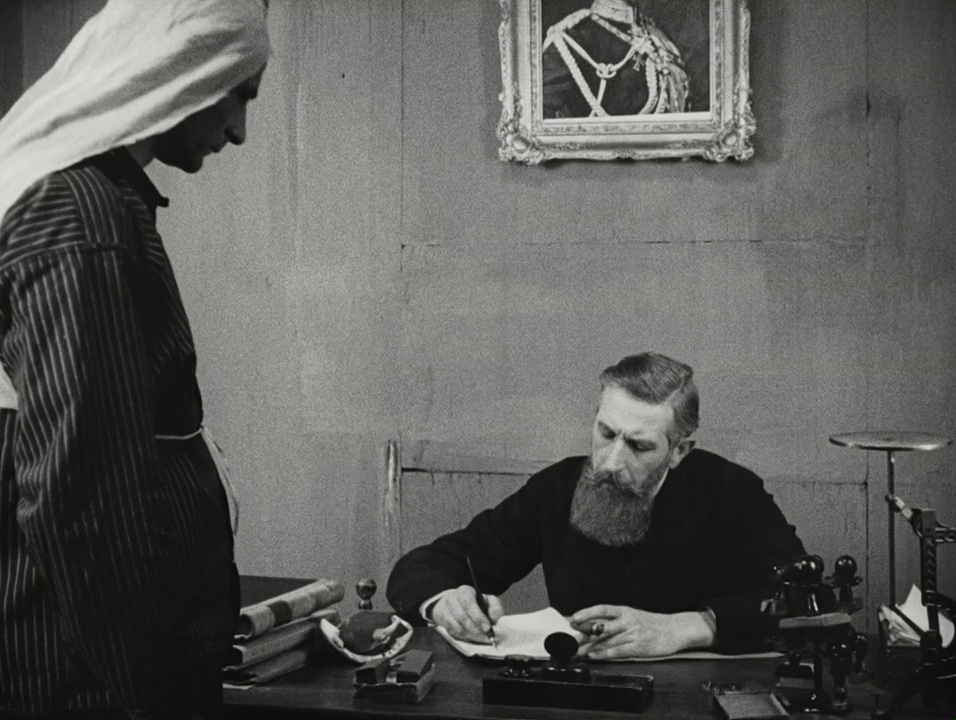

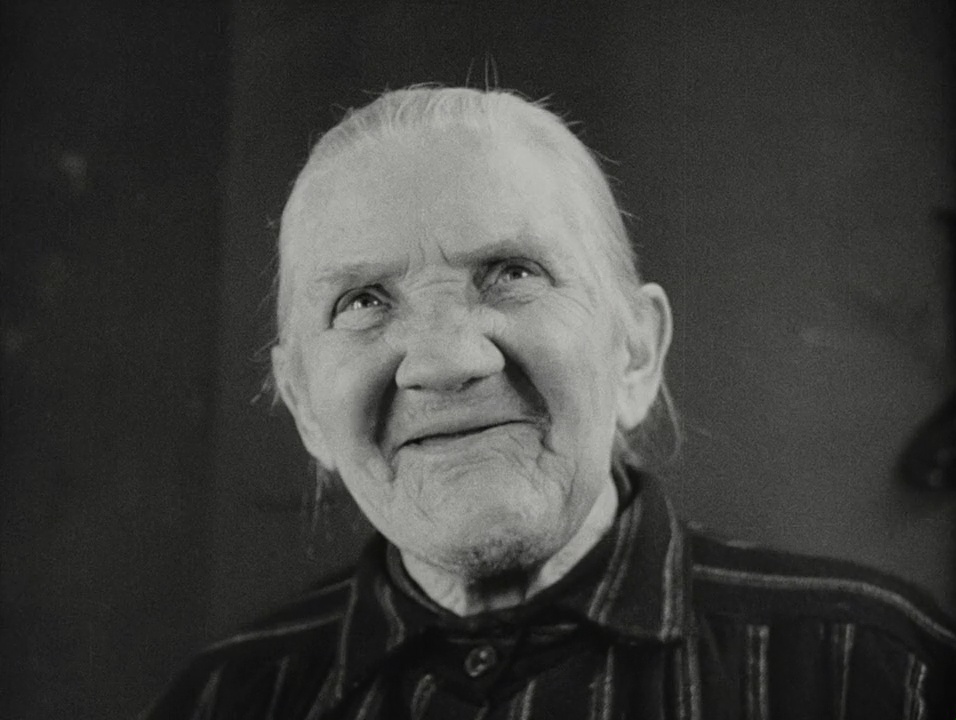

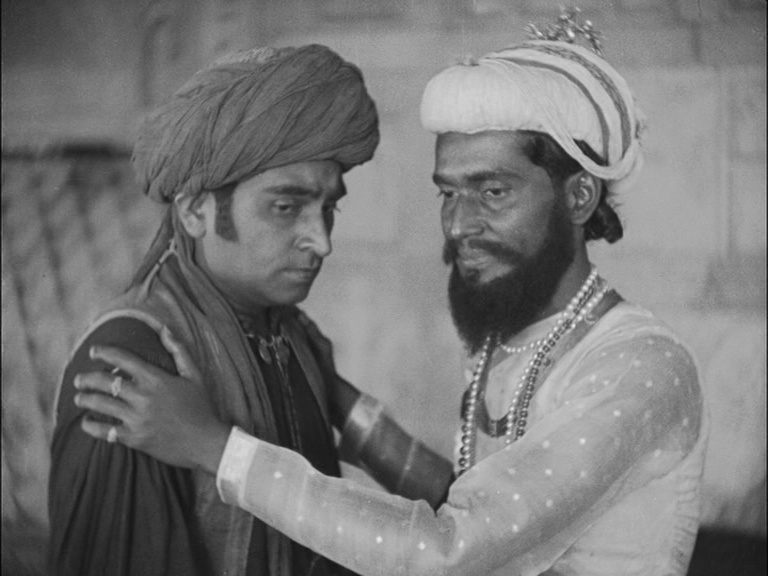

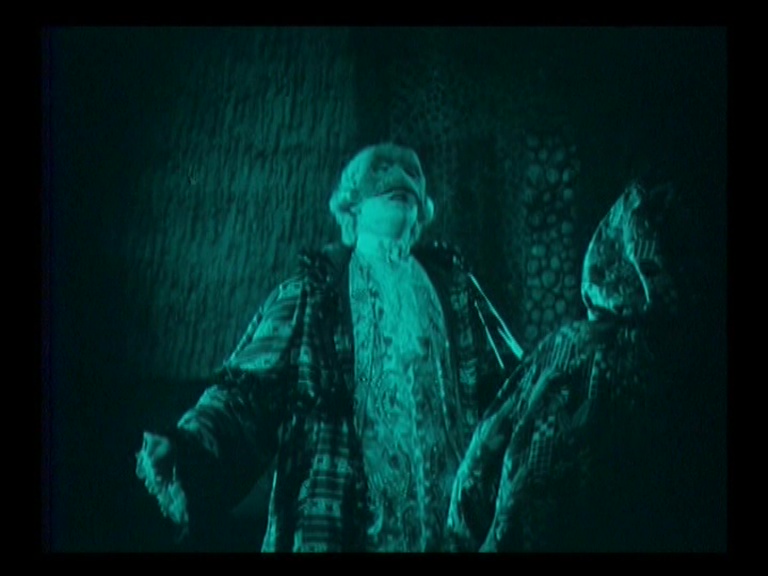

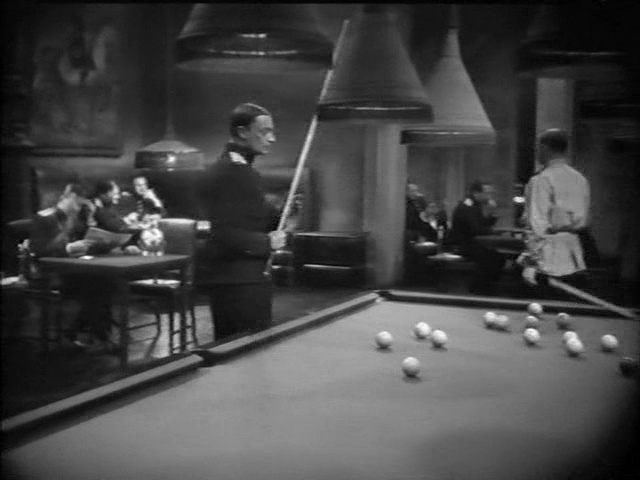

As the effete, elder banker Gunderman, the German actor Alfred Abel is suave and sinister. It’s a quiet, controlled performance. His character is so calm and collected, and Abel always keeps his gestures to a minimum. The occasional flash of an eye, the hint of a smile, the slight nod of the head, is enough to spell out everything we need to know. He’s not quite a Bond villain, but he nevertheless has a fluffy pet, a dog, that we see him fondling at various points in the film.

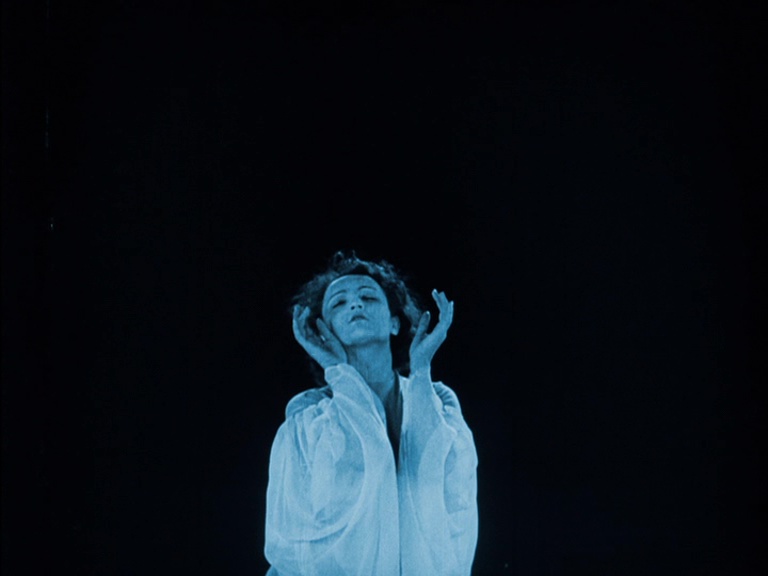

I turn next to Brigitte Helm because she is, alongside Alcover, by far the most exciting performance in the film. As Baroness Sandorf, she is draped in expensive furs or sheathed in shimmering silks. Her eyes out-pierce anyone else’s stare and her smile is a double-edged weapon. The way she walks or sits or stands or lies or lounges is so purposeful, so designed, so compelling. Even sat at a table across the room in the back of the restaurant scene, she’s somehow magnetic. She really was a star, in the way that I take star to mean—someone whose presence instantly changes the dynamic of a scene or shot, whose life seems to emanate beyond the film. But despite being the face of the new Blu-ray cover for L’Argent, and leading the (new, digital) credit list at the end of the restoration, she has surprisingly few scenes—and not all that much significance in the plot. Perhaps more of her scenes were in L’Herbier’s original cut of the film. Either way, I spent much of the film longing to see more of her.

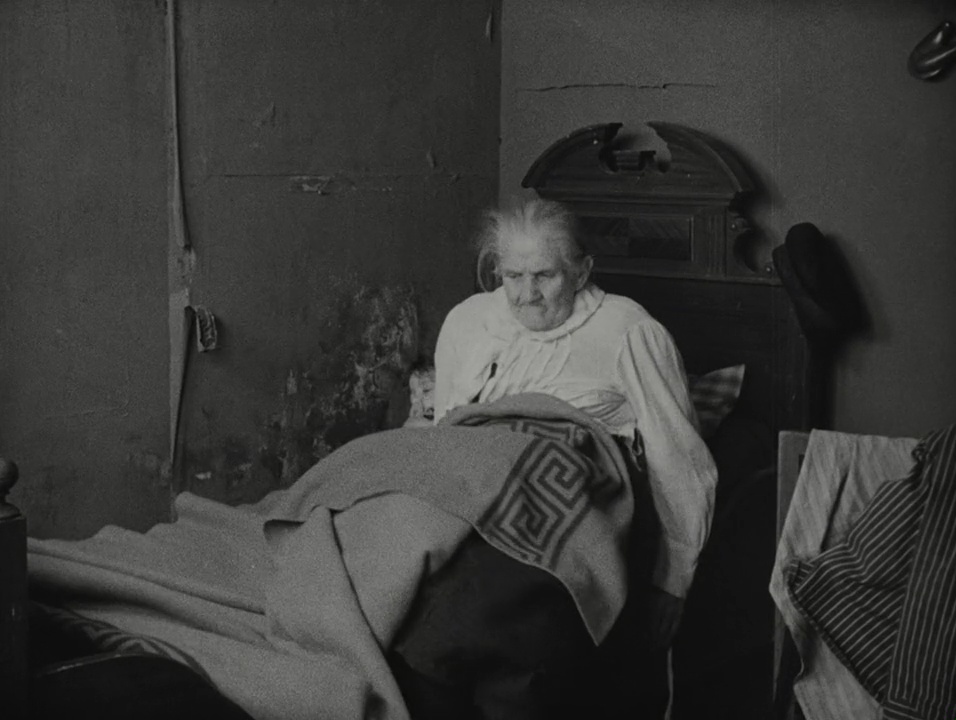

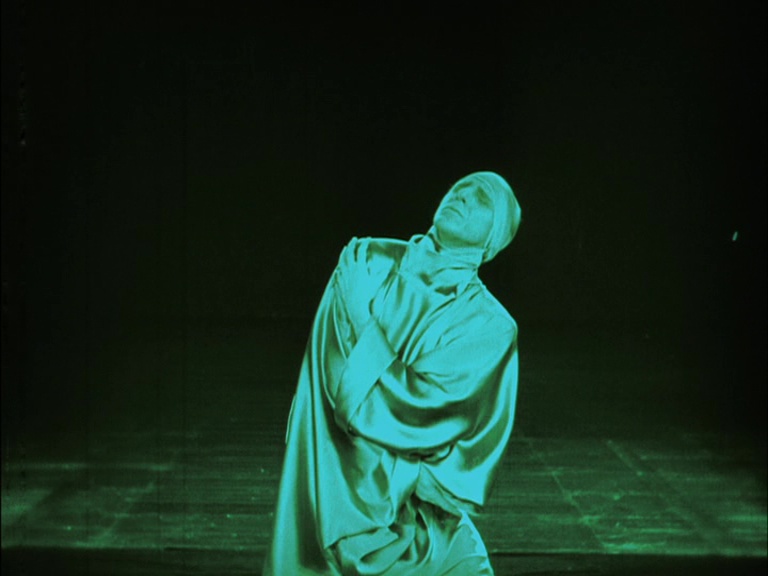

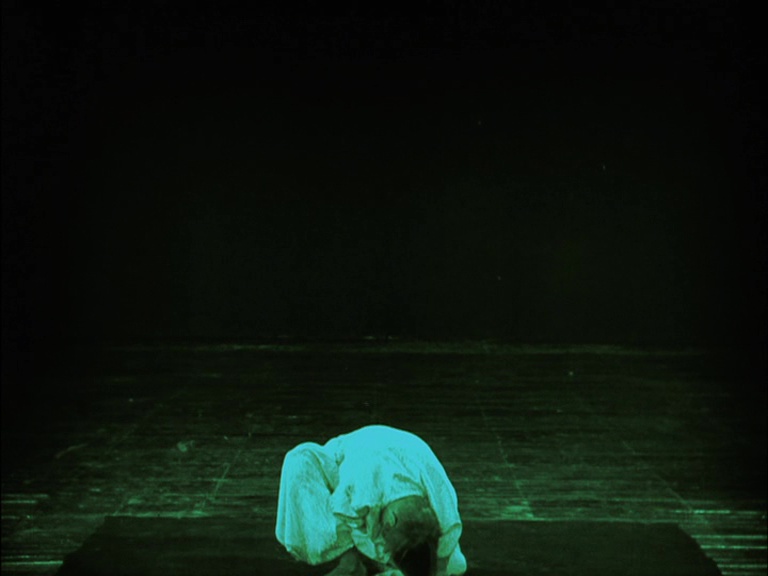

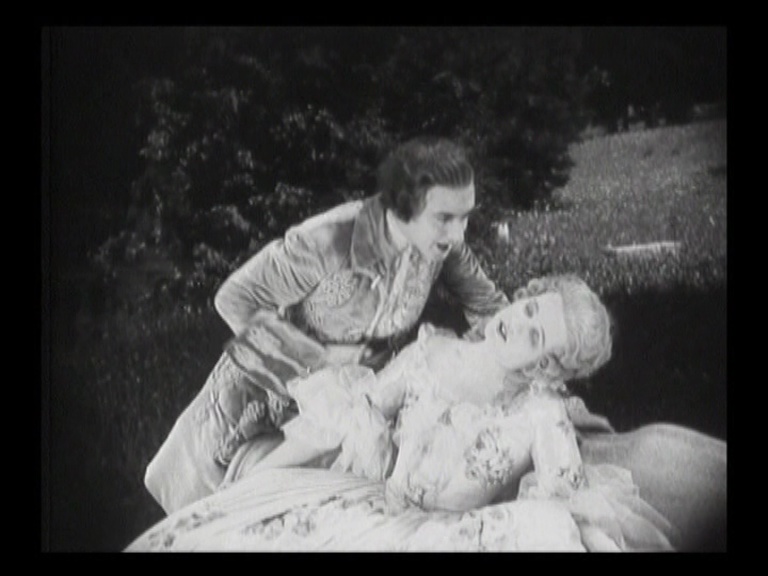

Conversely, as the “good” husband and wife ensnared by Saccard, I find Henry Victor (as the aviator Jacques Hamelin) and Marie Glory (as Line, Jacques’ wife) much less interesting. Their love never quite convinces or moves. I also found an uncanny resemblance between Marie Glory and L’Herbier’s regular star (and lover) Jaques Catelain. (And once observed, I couldn’t un-observe it.) I requote Noël Burch’s comment here on Catelain resembling “a wooden Harry Langdon”, and for the first half of the film I find Glory no less unconvincing. But as the film continues, and she becomes a more active agent—or at east, an agent conscious of her manipulation by Saccard—her performance finds its range and becomes more dynamic and engaging. But I still never buy into her marriage, which I suppose is an advantage to the extent it makes her appear more vulnerable once her husband is away—but undermines the fact that she is so steadfastly loyal to him. I know for a fact that I’ve seen Marie Glory in other silents, but I simply cannot bring her performances to mind. The lack of warmth or genuine feeling in this central couple if a problem for me. I find many of L’Herbier’s films emotionally constipated, and L’Argent is no exception.

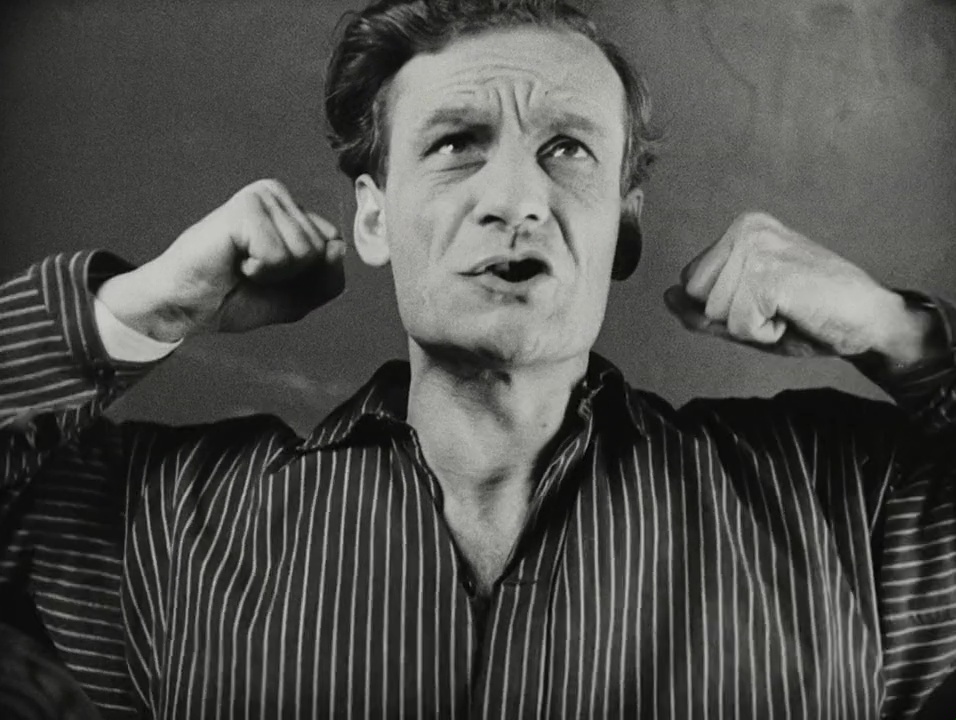

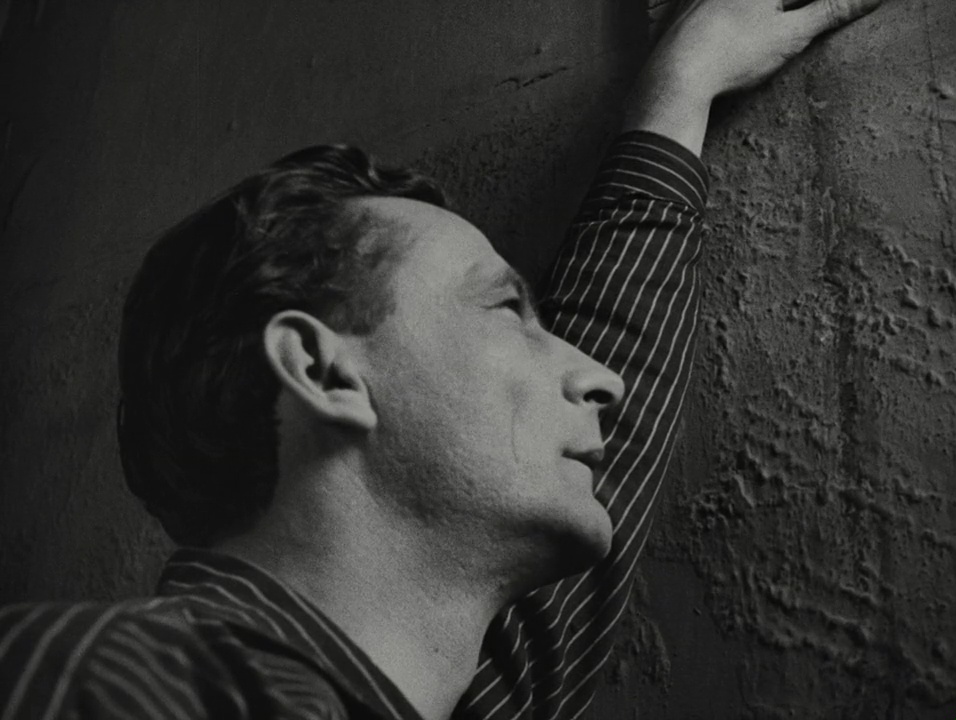

One other cast member to mention is Antonin Artaud as Mazaud, Saccard’s secretary. I find it very strange to watch Artaud in such an ordinary, unengaging role. Strange, even, to see him walking around in a perfectly ordinary suit. His presence—his familiar, compelling face—is welcome, but I’m not sure I can appreciate why he was cast. (His performance as Marat in Napoléon, the year before L’Argent, and as Massieu in Dreyer’s La Passion de Jeanne d’Arc, the same year as L’Argent, really overshadow this almost anonymous part of a bank assistant.)

Summary

Yes, I enjoyed rewatching this film. But I won’t deny that it has a certain coolness that stops me from truly loving it. I feel that way with much of L’Herbier’s work. To utilize what the translator D.J. Enright once said about fin-de-siècle literature, the films of L’Herbier tend to combine the frigid with the overheated. There is a surfeit of design, of aesthetic fussiness, but a dearth of humour, of human warmth. L’Argent is his broadest canvas, and it contains the most energetic, diverse, dynamic filmmaking of his career. It needs this formal invention to keep the story alive, for a film that revolves around financial transactions is at constant risk of becoming dull or incomprehensible. It’s like watching a three-hour long game of poker without knowing the rules. My attention never drifted, but I was close to being bored—despite the many wonderful things to look at, and the wonderful ways the film invents of looking. The film’s romantic storyline of the pilot and his wife is lacklustre, especially next to the sizzling chemistry between Alcover and Helm. Their scenes crackle and I wish there had been more of them. Would the 200-minute version of the film offer a more balanced drama, or would it exacerbate the distance between me and it? For all my reservations, it’s still a magnificent work of cinema.

Paul Cuff