Our last day of streaming from Pordenone. We begin in Germany (or possibly Istanbul) for an Anna May Wong vehicle, then make our way to America for some Harold Lloyd. Two chunky features to digest, so here goes…

Song. Die Liebe eines armen Menschenkindes (1928; Ger./UK; Richard Eichberg). On the outskirts of an “eastern” town. John Houben (Heinrich George) encounters Song (Anna May Wong), one of “Fate’s castaways”, and rescues her from a gang of roughs. He leaves, but she follows him back to his poor home in town. He is a knife-thrower and, after some initial hesitation, she moves in with him and joins his variety troupe. Posters advertise the arrival of Gloria Lee (Mary Kid) to the city. We see her with James Prager (Hans Adalbert Schlettow), a rich patron. Meanwhile, we see in flashback that John once fought and killed a man over Gloria – and John was presumed lost overboard, but survived when washed up on the beach where he met Song. At the Blue Moon café, Gloria sees Song dance and John throw knives. Gloria offers John money, while Prager flirts with Song. The next night, John goes to see Gloria at the ballet and visits her backstage – and confesses his love. Prager arrives and the two men exchange violent looks. John wants more money to impress Gloria so joins a gang of train robbers. The plan goes awry and Song rescues John from the rail tracks. But his sight has been damaged by the accident and during his knife-throwing act he wounds Song. John suspects Song of having betrayed the gang to the police. He attacks her and falls in a stupor: he is now blind. Song goes to Gloria to ask for help. Only Doctor Balji can help, but this will be expensive. Song comes again to beg for money but is offered only Gloria’s old clothes. Song sees money in her dressing room, so steals a couple of notes and leaves. Song returns to John in Gloria’s clothes. Blind, he mistakes her for Gloria, which devastates the lovelorn Song. She lies and says the money was from Gloria, so they go to the doctor. Gloria leaves the city, but Prager stays. He once more crosses paths with Song and says he knows she stole the money. He promises her a big engagement in one of his shows. She accepts and some time later she is star performer at more upmarket venues. Meanwhile, John is cured but must not remove his bandages for three days. He asks after Gloria, so Song says she will go to fetch her. She re-enters dressed in Gloria’s clothes. He rips off his bandages, sees Song, and furiously hurls her from the house. She mournfully heads off, while John discovers that Gloria long ago left the city. Song returns to Prager, who is angry she has been with John. He tries to force himself upon her and says she must decide between John and him. Song performs a sword dance, just as John enters. Started, she falls onto a blade. He takes her home. She opens her eyes in time to see that he is recovered and has brought her back – then dies. THE END.

An odd film. Made in Germany with a mostly German cast, Song was released as “Show Life” in the UK, and this English-language print is the one that survives. The restoration, by the Filmmuseum Düsseldorf, relied on what the credits tells us was a very limited amount of original 35mm material. But the result, while missing a small amount of material, is gorgeous to look at. The photography is superb, the tinting adding a lovey atmosphere to the exteriors of Istanbul, the cramped sets of John’s house, and the elaborate stage sets for the café, ballet, and salon. In particular, the opening shots of the coast around Istanbul (or wherever, doubtless, substituted for it) are gorgeous.

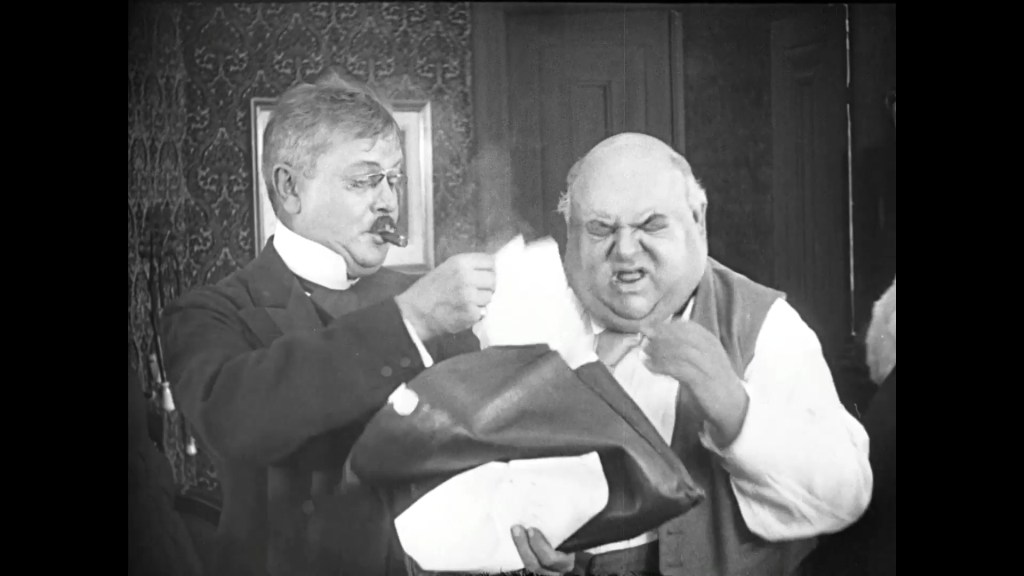

George and Wong are also captivating presences on screen. This was one of Anna May Wong’s most successful silents, and the film lavishes lots of close-ups on her. She is clearly a star, magnetic and fascinating, and even if the psychology of her character in this film is very sketchy, she gives a committed performance. But I was equally taken with Heinrich George, who made such an impression in Manolescu (shown at Pordenone in 2022). The man is a hulking physical presence – always gruff, always strong, always dangerous. When his character tries to be charming, he exudes a kind of over-keenness that threatens to become violence. He’s a fierce, brooding, never-quite-pitiable figure.

All that said, I don’t think this is a great film. As much as I like all the above aspects, the film as a drama is less than the sum of its parts. I simply didn’t care enough about the characters, or believe in the depth of the feelings they supposedly had for each other. Everyone feels rather like a stock character, which the performers all do their best with – but there’s only so far you can go with such a thin story. There are plenty of intensely concentrated shots (especially some close-ups of George and Wong), but these images don’t add up to anything of psychological depth or dramatic conviction. It’s lovely to look at, but I was underwhelmed with the drama. And although I like Wong and George, I never bought her love for him. (I think back to Manolescu, where George’s love-hate relationship with Helm was visceral on screen.) I can imagine that, looking just at the image captures here, Song may well look like a better film than in fact it is. It really does look good, but it needs more than that.

And so, to our final film: Girl Shy (1924; US; Fred Newmeyer/Sam Taylor). What can I say? This is a masterpiece. I’ve not been so moved and so delighted by a comedy feature in years. My god, where has this film been all my life?!

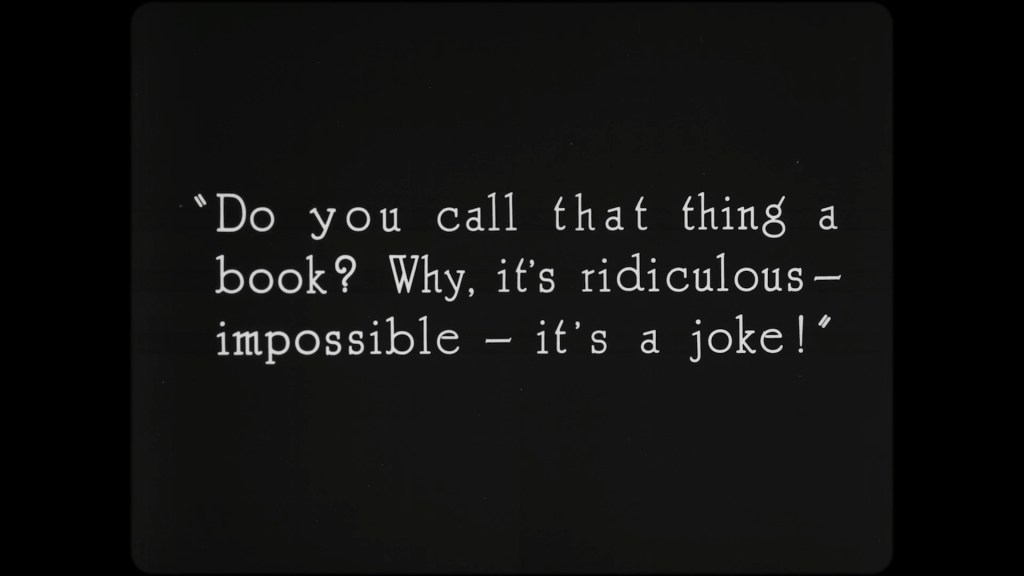

In the obscure small town of Little Bend, trainee tailor Harold Meadows (Harold Lloyd) lives with his uncle, Jerry Meadows (Richard Daniels). Harold is “girl shy”, helplessly stammering whenever he talks to a woman and recoiling at any intimacy. But he is also fascinated by women and has written a novel – “The Secret of Making Love” – in which (as we see via fantasy scenes) he imagines himself dominating them and winning their devoted admiration. On his way to the publisher with his manuscript, he encounters the heiress of the Buckingham Estate, Mary (Jobyna Ralston), and rescues (and then hides) her dog on the train. He describes the novel, and she is fascinated by it and by him. In Los Angeles, they must part – but Mary soon keeps driving through Little Bend in the hope of encountering Harold. However, she is being pursued by the louche Ronald DeVore (Carlton Griffin), a womanizer with a cynical eye for money. When Mary and Harold meet on the river in Little Bend, their romance is interrupted by Ronald, who also clashes with Jerry. The young couple are parted once more but agree to meet in town when Harold goes back to the publisher. In town, Harold is laughed at by the publisher and the entire publishing staff. He leaves, utterly crestfallen, convinced he is unworthy of Mary. When he meets her, he pretends that their romance was all an act for the sake of his new chapter. They part, and soon Mary reluctantly accepts Ronald’s proposal. But the publisher realizes that he can sell Harold book not as a drama but as a comedy: he sends a $3000 cheque. Harold, believing this to be the rejection note promised by the publisher, tears it up without looking – only for Jerry to spot the error. Realizing he is now able to marry Mary, and being told that Ronald is already married to another woman, he hurries to break up the marriage ceremony in town. After a madcap chase from Little Bend to Los Angeles, he arrives in time to rescue Mary and propose. THE END.

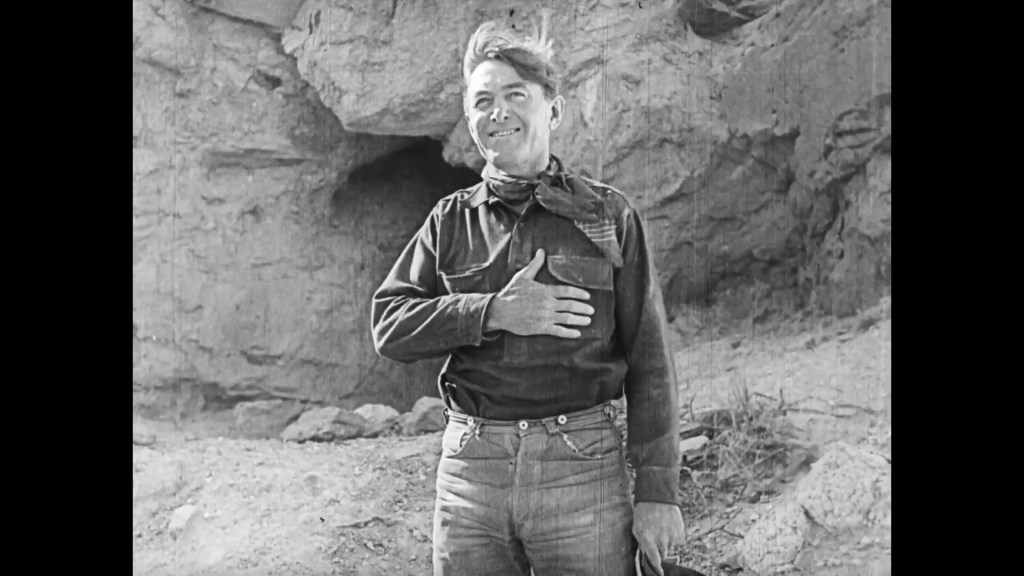

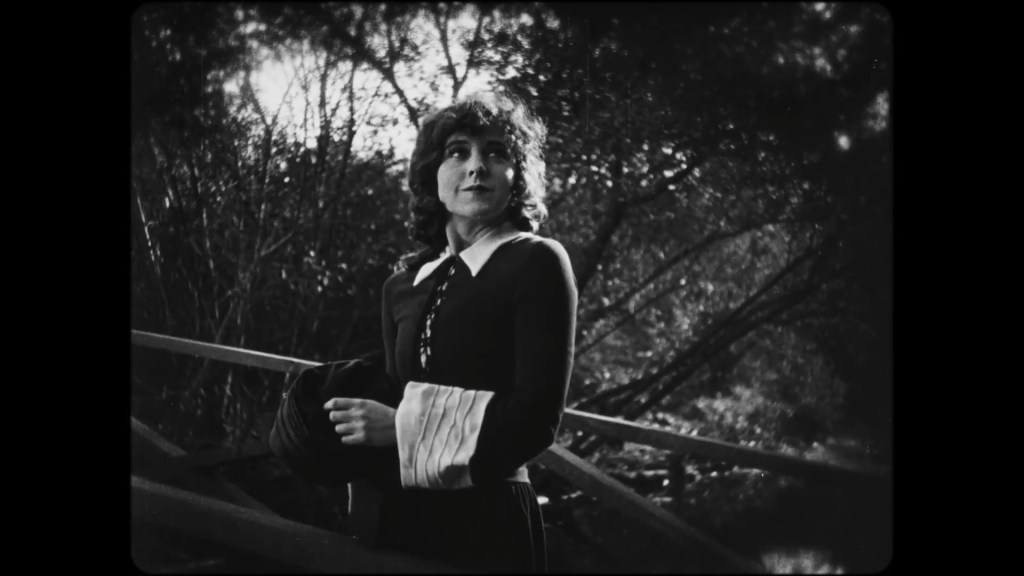

I’ll say it again: this film is a masterpiece. For a start, it looks beautiful. The photography is superb, the lighting excellent. The scene by the river, where Mary re-encounters Harold, is absolutely perfect: the evening light, the gentle softening of the background, the framing and composition of the bridge and reflections… oh my word, what a beautiful scene. It’s charming and funny and deeply touching. It’s rare in a comedy feature to be quite this moved, and not to feel grossly manipulated, but Lloyd somehow keeps the emotional tone perfectly balanced. His character is a foolish fantasist, but he is also capable of real kindness. When the publisher tells him to his fact that he’s a complete failure, I confess that my heart broke a little. The extended close-up of Lloyd offers enough time to let the impact of the words sink in for the viewer while we watch it sink in for Harold. His performance isn’t sentimental, it’s realistic – and that’s why its so effective. It lets you believe in him as a real person, and the memory of his fantasies of domination are left far behind. I cared for him here, just as I cared for Mary in the scene where Harold lies to her and breaks her heart. Again, the moment is so well pitched, so restrained, it’s simply heartbreaking.

It’s also a film of incredibly subtle visual rhymes and gestures. See how the uncle has on his knees a child whose trouser rear he’s mending; then how Harold is introduced likewise (rear first) through being bent over backwards; then how the gesture of sewing/intimacy is carried into Harold’s first encounter with the girl with the split tights. In these moments, the easy intimacy of the uncle for the child is awkwardly mirrored in the hoped-for-but-rebuffed intimacy of the girl and Harold. Harold is figuratively childlike but – unlike the actual child – cannot cope with the adult implications of intimacy. His introduction, bent over backwards, is a kind literal rendering of how he’s got things all backwards. (More crudely, you might say he’s introduced as an arse.) Then see how, in the novelistic fantasy, Harold spanks the flapper in the same posture that the uncle repairs the trousers. Here, Harold enacts a comically violent revenge on his inability to feel easy around women and their bodies: far beyond his real self’s shunning of all contact, this is not the consensual middle ground of intimacy but the extreme of physical possession. It’s funny, certainly, but a little unsettling. Here is the loner fantasizing about smacking a woman for pleasure.

But the film’s visual rhymes also signal that Harold knows in principle, and will learn in practice, how not to treat women. In the first novelistic fantasy, we see Harold put his hat and cane over the outstretched arm of the vamp; in the real world, we see Ronald put his hat and cane over the arm of the Buckingham’s maid. The latter situation reminds us of the callowness of Harold’s alter ego, but in reality, the situation is more sinister. For Ronald’s gesture with the hat conceals (to the lady of the house) the fact that he’s groping the maid’s hand. So too, the placement of the cane over her arm makes it an extension of his own touch. The maid clearly feels uncomfortable and so, surely, do we. It’s a marvellous indication of how the fantastical scenario of Harold and the vamp becomes troubling when we see it enacted in real life. The maid, unlike the vamp, is a woman without power or recourse to self-defence. Then see how the gesture with the cane appears again as Harold, seeing Mary’s beloved dog left behind off the train, uses his cane to hook the animal from the ground onto the moving train. Here the cane is used for comic effect, but it’s also a gesture of sympathy, of kindness: he’s performing a good deed, a selfless one. (Perhaps there is an unconscious desire to use this act to make contact with the girl – but Harold is too shy to follow through, and spends the next scene desperately trying to avoid Mary.)

The rhymes are also there with Mary and Harold. They are forced to sit next together when the train takes a bend and Harold falls into place next to her, just as (later) on the river Mary falls into Harold’s boat. Their two treasured mementos of the train journey, the box of biscuits (hers) and the box of dog biscuits (his) are objects of veneration, things to hold in the absence of the real person. On the river, seeing the other person with their token of love indicates to the pair that their feelings are reciprocated, just as – in the first variation on this rhyme – the devaluation of the token is a rupture of their relationship. This occurs when Harold, having been rejected by the publisher, decides it’s best that someone destined to be a failure should not disappoint Mary. He breaks up with her and claims that all his words were a mere scenario for his book. He immediately hooks up with a passing girl, who had shown interest in him a few minutes earlier. They link arms and he then buys her a box of biscuits – the same brand as he had given to Mary on the train. The replication of this gesture is deliberately hurtful, a kind of parodic rhyme that devalues (while also re-emphasizing) the initial parallel of the lovers’ tokens. Later, when Harold receives the publisher’s cheque but (believing it to be the promised rejection note) tears it up unopened, the very next scene creates a poignant rhyme. Here, Mary contemplates the cover of the biscuit box that she has torn up and now reassembles. The rhyme between torn cheque and torn box suggests the inopportune rupture of something that would bring success and happiness – and (in Mary’s scene) the desire to repair the damage. Harold will soon piece together the cheque, matching the image of Mary’s reassembled package. With both halves of this parallel repairing achieved, Harold sets off on his race to the rescue. It’s such a brilliantly organized, beautifully staged use of props and gestures. God, what a good film this is.

Of course, I’ve hardly said just how funny a film this is. The long sequence on the train, when Harold first avoids Mary then has to sit next to her, is exquisite. I particularly loved the series of gags involving his (real) stammer and (feigned) cough. Lloyd manages to make these essentially acoustic jokes work perfectly for the silent screen. His stammer involved him contorting his mouth: first his mouth hardly opens, he purses his lips, the breath fills his cheeks; then his mouth his fully open, stuck in a different register, and still no sound emerges. It’s the physical movement of speech, its physical articulation, that works so well: here is speech visually arrested in its various stages. The coughing gag – where Harold has to mask the sound of the dog’s barking – works so well because Lloyd must express the cough purely visually: he has to attract the guard’s visual attention, not just aural attention, so his whole body performs the cough. The sheer extension of this sequence is part of the delight: it runs and runs, forcing Harold to keep finding new ways of doing the same thing. (In this, it foreshadows the far greater physical effort of his race to the rescue, where he must once again keep finding new ways to overcome essentially the same problem.)

The final sequence – all thirty minutes of – is astonishing. I can’t possibly go through all the gags, but the one that made me laugh the most was the “Road closed: diversion” gag. Lloyd’s car goes over a bumpy road that makes the vehicle buck and bounce. The particular framing of the medium-close shot of Harold at the wheel, bouncing helplessly along, is wonderful – but it’s the moment when the car finally regains the main road that rendered me helpless with delight. Here, the car has been shaken so badly that the entire vehicle is now a shaking wreck. Like the sensation of seasickness after returning to dry land, it’s like the car and its driver are now unable to cope with the smooth tarmac. Within the wider context of the chase – in simple terms, one damn thing after another – it’s such a bizarre image, and such an unexpected twist, that I was rendered almost insensible with laughter.

The major stunts – Harold unwinding the fire hose, hanging off the cable car cable, the near-crash of the horses – are superb. The moment when one of the horses slips and slides along the road is genuinely breathtaking, and the tracking shot of Harold riding hell-for-leather are as remarkable in their own way as some of the chariot race footage from Ben-Hur (1925) – Lloyd’s film even foreshadows many of the same dazzling camera positions. And to conclude this finale with Harold’s inability to actually say why the marriage is invalid is such a brilliant pay-off to the preceding derring-do, I was won over again by his character, and by the film’s sense of comic timing. What an astonishing sequence, and what a brilliant film.

The music for the film was the first and only orchestral soundtrack offered for the streamed Pordenone programmes. The Zerorchestra provides a jazzy beat throughout. It keeps things moving along, although its default mode of extreme busyness sometimes lost interest in the very precise, varied rhythms of the scenes. What I admired most was the way the score knew when to keep quiet and reduce its forces for the piano alone, or even silence. The moment when Harold is rejected by the publisher was rendered all the more moving by the pause in the music. The feeling of dejection sinks in so perfectly here, the choice to pare the music back to virtually nothing works so well. The (I think , entirely necessary) use of sound effects – for the whistle, the typewriter, the dog – are subtly done, becoming a part of the music rather than intrusions into the silent world. A strong score, well executed. (Since seeing the film yesterday [actually, by the time you read this, the day before yesterday], I have dug out the version released on DVD some twenty years ago, which features an orchestral score by Robert Israel. This is a more traditional score than the Zerorchestra’s, as the latter mode of jazz certainly postdates the era of the film. I also confess that my own taste leans more toward the kind of orchestral tone painting that Israel compiles. He also has the benefit of a full symphony orchestra, so the sound is lovely and rich. I hope the film gets a Blu-ray release, perhaps with both scores as optional soundtracks. This is a film I want to watch again and again.

So that was Pordenone, as streamed in 2024. As ever, I emerge from this week-and-a-bit exhausted, without even having left my house. (Having in fact been practically housebound because of fitting in a festival around work.) Having followed a little of the writing and photographic record of the on-site festival, I am also very much aware that those who went to Pordenone saw an entirely different festival. It’s quite possible that someone there could have missed many, most, or all of the films that I saw streamed. My memory of the content of Pordenone 2024 (streamed) will be entirely distinct to the memory of Pordenone 2024 (live) for those who attended in person. I have quite literally experienced a different festival to those at Pordenone. I also regret that I have not had time (or have not made time) to watch Jay Weissberg’s video introductions, or the book launch discussions, all of which are a significant chunk of the material made available online. I suppose these, in particular, offer a more tangible sense of the festival on location. My relationship with streamed content remains very much limited by time. I fix onto the films and abandon the rest, “the rest” being precisely that content which offers contact with the people and places of Pordenone in situ. But without taking the time off to entirely devote myself to the festival, I cannot see this changing. And why take a week off when all I’m doing is standing before a screen? Oh, the ironies…

Nevertheless, I remain exceedingly glad to have seen what I have seen. Thirty euros for ten generous programmes, shorts and features, is good value, especially given the rarity of most of the material. It’s a further irony that my favourite film of the whole festival – Girl Shy – was the most readily available of all of the ones I saw. But I welcome the chance to see anything and everything, even the passing curiosities and stolid duds, simply because it’s good to explore any culture with which you are not familiar. One day I will go to Pordenone in person, whereupon I’ll probably regret not being able to take image captures and have the time to write. The irony abounds.

Paul Cuff