This time last year saw me start this blog with ten days of posts attending the Pordenone silent film festival from afar. This year, I’m once more not making the trip to Pordenone. It’s the same reasons: time, money, and the budgeting of annual leave across the year. But yet again I am inexorably drawn to the idea of Pordenone, and what follows is the first of another ten daily posts about the online version of the festival. Day 1 sees a two-part screening. First, an hour-long programme of slapstick shorts (with music by Daan Van den Hurk). Second, a feature film western (with music by Philip Carli). We’ve barely a moment to lose before the next films are upon us, so for goodness’ sake keep reading…

Le Torchon brûle, ou une querelle de ménage (1911; Fr.; Roméo Bosetti). The wife serves the husband a meal. The husband objects to the meal. The situation snowballs. Crockery is thrown. Then furniture. Soon the husband is ripping cupboards off the wall and hurling them out of the window in fury. (Down below, outside, two policemen are slowly but inevitably buried in the defenestrated wreckage of the home.) When the entire room is broken in pieces or hurled out the window, the couple turn on each other with bare hands. They role around on the floor, down the hall, down the stairs, into another room, out the window—where they land on top of the policemen. They keep on rolling: across the street, under a car (still fighting), under a horse and cart (still fighting), through a mob of merchants and shoppers (trashing a stall en route), down the street, down a manhole, into the sewer. Then a wonderfully bizarre twist: the film is reversed and the couple whizz back up the manhole and out into the street, up a set of stairs, up the road, over the broken pile of furniture (before the eyes of the disbelieving policemen), then hurl themselves through the air back into their apartment. The end. A charming, silly, anarchic, violent piece of slapstick. And a neat comment on the escalation of an argument that can quite literally go nowhere but return to its source—presumably to begin again the next day.

Rudi Sportman (1911; Aut.-Hu.; Emil Artur Longen). A man and woman sit outside a tennis court. The man irritates the woman, the woman irritates the man. Presumably frustrated by his inability to smoke and read the paper in peace, the man begins the next scene trying to get on a horse. He does so backwards, forwards, falls off, remounts, then is jettisoned by the horse. Frustrated again, the next scene shows him trying and failing to ride a bicycle. The woman from the first scene ends up being run down and chasing the man away with a stick. The man (still dressed in frock coat, shirt, and tie) now bunders onto a football pitch, where his attempts to enter the game end in him being chivvied and kicked and beaten by the players. Enthused (and presumably suffering from the debilitating effects of his various falls and beatings), he next tries hurdles, then tennis. (All the while, there are glimpses of a lost European world in the background: the buildings, the officials, the way of life… What happened to those young men playing football in 1914? What became of the lads diving into the pool to save the hapless rower? Did the boat attendant become a military attendant?) The man’s enthusiasm sends him stumbling, falling, summersaulting—and leaving. Next to the rowing pool, where he swiftly ends up in the water. Reprimanded by the attendant, he finds solace in the final scene with the woman—a man in drag, who might or might not be his other half, who now seems both pleased that the man has been severely injured and pleased that he has returned to her. She gives him a kiss, licks her lips, and the film ends.

At Coney Island (1912; US; Mack Sennett). It’s familiar Mack Sennett fare: two alternately grinning and gurning men fight over a woman. Around them, the swarm of life: real life in 1912 Coney Island, with groups of Keystone players dotted around, embodying grotesque families, arrogant fathers, scurrying girls, violent adulterers, and a midget policeman. A chaotic mess of desire sends men and women scuttling into fairground rides, and (just as quickly) out again. Wives chase after husbands, children scream. Couples illicit and singles jealous hurl after one another down terrifyingly unsafe rides, stopping only to shake their fists at each other, gurn, jump up and down in fury. Soon a kind of turquoise dusk descends. But why should continuity concern anyone in this madcap world? The dancehall is a light rose, the tent a bright orange. Time passes, but the men keep chasing their desire—and I’ve hardly had time to unpick who is being chased by whom, or whether the policeman is after the father or the lover or the child, when the film ends.

En Sølvbryllupsdag (1920; Den.; Lau Lauritzen Sr.). “Their Silver Wedding Anniversary”. Already the title bodes ill. The wife wakes Mr Taxman with the news of their anniversary. In his separate bed a little way from the wife, the Taxman—a walrusy sort of fellow—yawns, turns from gurn to grin, kisses his wife, and mourns their lack of money. Talk is of money, but it soon escalates: “You’re a lazy, fat, spoiled bastard—so the woman from the culture centre says”, his wife informs him. “And you are an old, mean, sleazy sea-goose. That what I say!” Soon these two heavy-set middle-aged people are out of bed and shouting at each other. In tears, the wife leaves home. Chuntering, the Taxman goes back to bed. Cue a passing brass quartet. They troop up to the Taxman’s house and start blasting him a serenade. Whereupon… he weeps! It’s weirdly touching, this comic scene: a reminder of time past and passing, of regret and age and loss. But it’s also funny, for soon the emotion shifts gear: the Taxman throws a jug of water out the window to chase away the band. A visitor to the taxman (now deemed a lawyer in the title). He relays an offer of 25,000Kr from an uncle, but only on the condition that the agent reports that the couple lead a harmonious life together. The husband leaves the agent with a large case of cigars, a glass, a soda siphon, and a whole bottle of spirits. He goes on “The Wild Hunt for the Silver Bride!” (Meanwhile—and this is a lovely touch—we see the agent contemplate the bottle, turn it away from him, then give up and slowly fill his glass to the brim. A tiny dash of soda later, he settles down to his drink.) Where is Ludovica? She’s gone on a trip. We follow the jacketless husband through the streets of Copenhagen—these glimpses of a century-old world are always so beautiful—and into a women’s meeting, where he tries to silence the speakers at the podium so he can yell for Ludovica, only for the entire hall of women to run him out. (Meanwhile, the agent pours a second and third glass—and by the third he misses the glass with the soda altogether.) The man meanwhile charges into a women’s bathing area and peers into each and every booth, only to be chased and ejected yet again by a crowd of women. (A fourth glass goes down the agent’s throat.) The man returns home, finds his wife in tears on the stairs, and hurries her in. The agent, now drunk out of his head, sits giggling in the chair where we left him. But he can hand over the cheque, amid blasts of cigar smoke, to the old couple. “Remember: you can’t buy silver for gold!” a final title reminds us. (And a final treat in the last title: an animated logo for Nordisk Films, complete with real bear atop a globe.)

From Hand to Mouth (1919; US; Alfred Goulding). Harold Lloyd is The Boy, “hungry enough to eat a turnip and call it a turkey”. We are introduced to various kinds of will (people and objects). Will Snobbe gets my favourite intro: “His head would make a fine hat rack”. Meanwhile, outside, the Boy, amid scenes of poverty. (How long since scenes of outright poverty and hardship were the mainstay of American comedy?) He gazes longingly at a cheap restaurant. He puts on a napkin, takes a think bone out of his pocket, and chews on it. The Boy steals a biscuit, which is then stolen by a child. He chases the child, retrieves the biscuit, but the child is so cute he gives it back to her. Meanwhile in the lawyer’s office (the lawyer being called Leech, of course), the will is being fought over. Snobbe and Leech are in cahoots. The plot proceeds. Child and Boy (now friends) find cash, buy food—only to find the money is counterfeit. (They have also befriended a dog with a broken paw, who—just as they drop their unpaid-for food—drops his unpaid-for food.) Boy meets Girl, who rescues him from arrest. Cue various lost wallets, found wallets, biffed policemen, angry policemen, a kind of whack-a-mole sequence with the Boy popping up between two manholes, and a high-speed chase that mashes the Boy’s chase into the plot handed down from Snobbe to his ruffian underlings. At night, the Boy accompanies them on their robbery. A delightful gag about opening a window (assuring the band he knows how to jimmy open the window, the Boy systematically smashes it with a crowbar) is accompanied by a little gag in the titles: an anthropomorphic moon looks at the dialogue on each card, then appears to laugh at the payoff. Of course, the house being robbed is the Girl’s, and the Boy (after trying to eat the entire larder) soon takes her side in the robbery. Via a dazzling chase (Boy lassoing a car from a bicycle, which he then rides without steering), the Boy tries to summon the police to help him. None are interested, so he summons them via a series of vengeful acts: he hits them, insults them, hoses them down, vandalizes a police station (then reaches through the smashed glass to pull a cop’s nose)—until dozens of officers are pursuing him to the villains’ lair, where they treat the baddies to some good ol’ fashioned police brutality. Boy and Girl arrive just in time to scoop up the inheritance from the lawyer and chase out Snobbe. A lovely final scene shows Boy and Girl, with street child and dog-with-broken-paw, eating a hearty supper. A final longing look of love, as the Boy sneaks a spoonful of her pudding. An absolute delight of a film.

Cretinetti che bello! (1909; It.; André Deed). “Too beautiful!” a title announces, and it needs to do so to clarify the almost inexplicable events that follow… A man in an absurd wig and jazzy waistcoat is invited to a wedding, so he dons an enormous top hat, clown shoes, and powders his face with an inch of powder. Now with monocle and cigar, he marches along, looking so beautiful he attracts women (all men in drag) from his house, a gelato stall, and a park bench. At the wedding, more women (most of whom are again men in drag) fall for him, including the bride and the women of both families—who chase him outside, through a park, and tear him—quite literally—to pieces. Horrified and disappointed, they run off. But the pieces start moving around and eventually reanimate themselves, so that Segnor Cretinetti delightfully comes back to life and jigs with glee. A joyfully silly film, and a nice way to round off the programme of shorts.

Next, our main feature presentation…

The Fox (1920; US; Robert Thornby).

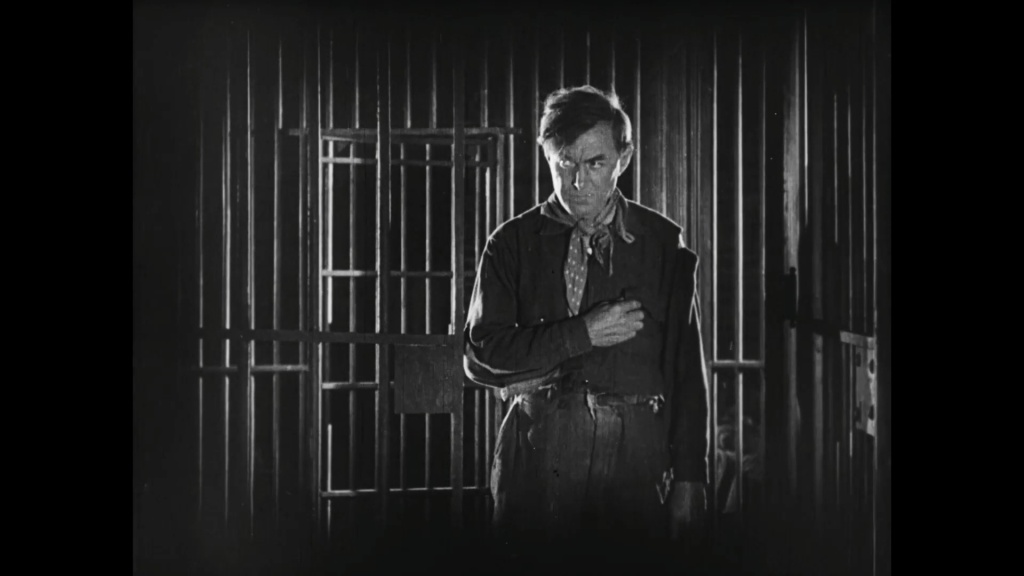

A sleepy town on the edge of the desert. Suddenly, an eruption of violence, horses and cars and lassoes careering through the streets. The Sheriff is called for, violent gangmen are everywhere. Enter Harry Carey as Santa Fe. (“They didn’t know where he came from, and they didn’t care.”) He sees a bear tamer threaten a child. Cue fistfight, the tamer using the bear for self-defence(!). Santa Fe chases off the father, only for the child to chase him. The child admits the man wasn’t his father. “He found me, just like you”. The two outsiders make friends. One mishap with the law later, and the child is effectively adopted—they are put in the same cell together. But the Sheriff’s daughter Annette pleads for Santa Fe’s good nature. The old sheriff offers Santa Fe a job. But the child remains in jail as a “hostage”, to make Harry more liable to do the Sheriff a favour. First, Santa Fe takes a job as a porter in the local bank. (Carey is very funny here, and throughout: the way he playfights, the way he tries to kill a fly, the way he holds a duster.) But Santa Fe’s here to spy on the goings on behind-the-scenes at the bank. Coulter, the dodgy president, enlists the help of his clerk Farwell to take the fall for his own emptying of the bank’s funds.

Meanwhile, Santa Fe is at a restaurant—carrying stacks dishes, rushing with the precarious skill of a comedian. In the desert, Farwell is captured under false pretences (all according to Coulter’s plan). In the restaurant, Santa Fe prepares a surprise for some gang members: mustard in their coffee. But to his surprise, they love it: “Now that’s good coffee!” But a fight nevertheless ensues, with hurled furniture and crockery. “Can you only fight?” the Sheriff asks, bringing him back to the jail. Now the gang, drunk, barge in and start a fight in a store. But the Sheriff arrives, only to be bested by the gang. (In this section of the film, there are some very nice low-key lighting for the night scenes. And a nice shot of Santa Fe in jail, beautifully lit, highlights on the bars and his shoulders—the same light that catches the flies buzzing in the foreground.) Santa Fe comes to save the day, gun in hand, and earns the respect of the Sheriff and Annette. His esteem warrants him a better hat and a sturdier pair of trousers: he slowly starts to look the part of the cowboy rather than the hobo. He heads into the desert to chase the gang and the missing clerk. He finds the “Painted Cliff Gang” hideout in the desert cliffs: a kind of “city”, hidden from the outside world. He finds and rescues Farwell, then returns to the town. Santa Fe reveals that he is a government agent and offers his full support.

So, to the desert, where the gang—armed with Lewis machine-guns—fight the forces of town and law. They are waiting for the cavalry. And they arrive in style, these “Veterans of the Argonne”. Hails of bullets, falling bodies from cliffs, sticks of dynamite, Santa Fe climbing cliff walls, a huge explosion, the charge of the army, machine-gun fire sawing through a bridge support, “waves of lead and cold steel”. The bad guys are marched off and the cavalry chase after Coulter. But it’s Santa Fe who finds him, and the missing funds. Various happy endings ensure: Farwell marries the sheriff’s younger daughter, while Santa Fe goes off with Annette and the child—who Santa Fe hopes to enlist in the army. The makeshift family ride off into the desert. The End.

Day 1: Summary

A breathless start to the online festival. I found the hour of slapstick from across the globe an absolute delight. Even the least cinematically interesting (Rudi Sportman) had the delight of its real locations in a lost world, a lost time. Pratfalls in the foreground, history in the background. And talking of comedy, I was surprised by how many comic touches there were in The Fox. It was the first complete Harry Carey film I’ve ever seen, so a real treat. And a surprise, too. For I could imagine Buster Keaton or Harold Lloyd playing a similar role to Carey’s “Santa Fe” (the outsider hiding his physical abilities while timidly wooing the girl of a patrician figure), and the stray child could be a companion for Chaplin. Even the way Carey flirts, or looks longingly, is a little comic—comic in the way he’s so shy, and turns away when the girl catches him lingering. I like the way he slowly accrues the imagery of the cowboy: first the gun, then the hat, the jeans, and finally the all-action heroics of the finale. He moves from smart outsider, impressing with his deft touches and wit, to become the lawman and gunfighter of physical action. A solid, compact, oddly light film. (I admit, I’m not much for westerns—and I did prefer the slapstick to The Fox today.) A lot to see, but all new to me. And no time to dawdle! It’s only day one and already I feel the schedule nipping at my heels…

Paul Cuff