Today we head back to Italy, this time for a contemporary drama. Brace yourselves – this one is a stunner…

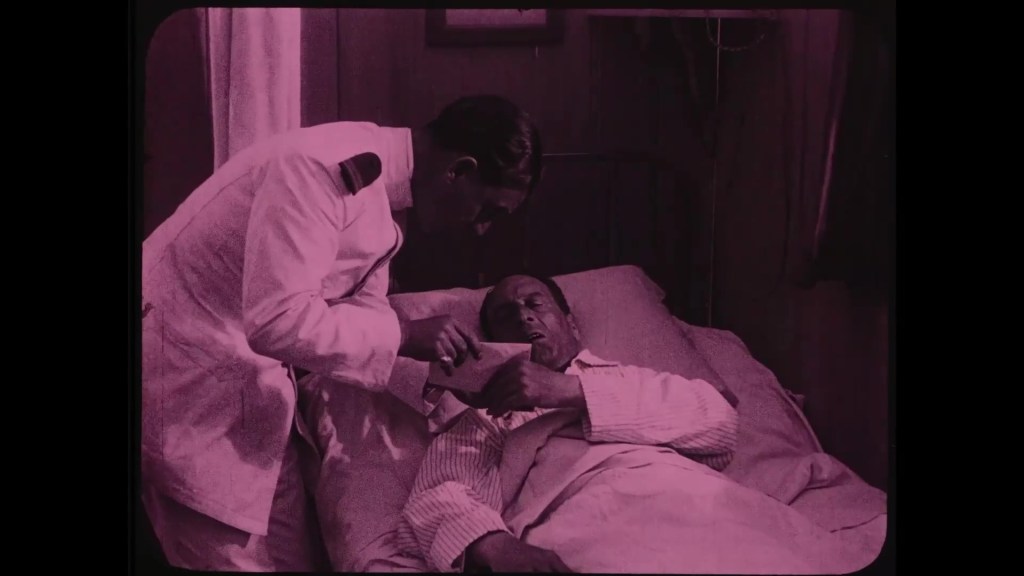

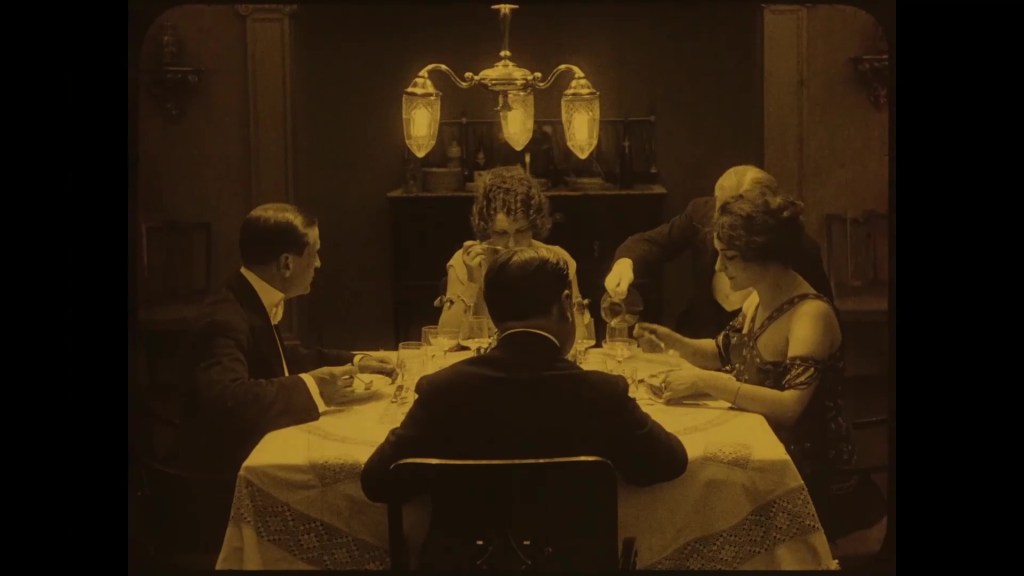

L’Ombra (1923; It.; Mario Almirante). The painter Gerardo Trégner is married to the passionate, sporty Berta. Elena Préville, Berta’s friend and distant relative, comes to visit. The naïve “little doll” who arrives is soon transformed into a fashionable belle. She also takes painting lessons with Gerardo. Alberto Davis is in love with Elena and seeks Berta’s blessing and help. Elena likes Alberto, but it is not a love match. Nevertheless, her guardian assents and the pair marry. After the wedding, Berta collapses – and, barring a miracle, is feted to remain paralyzed. Berta sinks into despair, refusing even to look at herself in the mirror. Elena returns to offer her support, and Berta grows suspicious when Gerardo spends nights away from home – preparing paintings for a major expedition. Years pass. Gerardo has become famous, but Berta remains at home – living solely for her love of her husband. One day, Elena visits and announces that she is getting divorced. Both women harbour secrets: Berta has regained the use of her limbs, while Elena has had a child with Gerardo. Gerardo completes a portrait of his son, but Berta – now recovered enough to walk – visits his studio and wonders who the portrait depicts. Gerardo returns and finds Berta recovered from her paralysis. But she finds piano music and flowers, and realizes that both belong to another woman. The pair argue, and Berta discovers that the child is Gerardo’s son – and that Elena is the mother. Berta flees to a church, where she begs God to give her back her paralysis, which would be easier to bear than the knowledge of Gerardo’s infidelity. She prepares to leave for a long treatment in Vichy. Gerardo attempts a reconciliation, but Berta keeps imagining his child. In the meantime, Berta’s godfather Michele suspects that Elena is secretly seeing Alberto again. Berta confronts Elena, accusing her of cowardice and treachery. She orders her to leave, and takes possession of the child – and Gerardo. FINE.

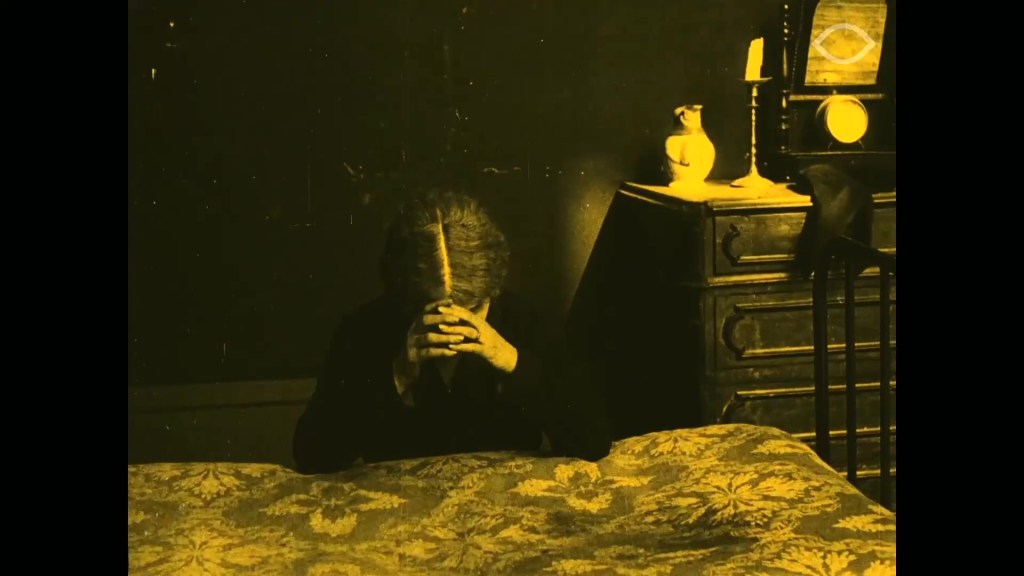

What a superb film this is: a stirring, grand melodrama, wonderfully realized. It unfolds through a pleasing blend of long, slow scenes and sudden, startling transitions. Secrets are well hidden in this structure, allowing full space and time for the grand scenes of drama to unfold. Berta’s paralysis, her miraculous recovery, her discovery of Gerardo’s secret, her confrontation with Elena – these are given an often surprising amount of screen time, and are remarkably effective and affecting. The whole thing moves like an opera, complete with visual leitmotivs and repeated metaphors. I love how up-front L’Ombra is about its central image. When she is paralyzed, Berta tells Gerardo that she is “but a SHADOW in your life… a SHADOW full of sadness under the sun of your glorious future… / But in your heart, you see, my place must remain untouched, waiting for me to take it back when this SHADOW lights up again…”. I do love it when a character cites the name of the film, especially when that title draws our attention to it with upper case text! But the dialogue is also as grand and slow as the film. Its long scenes allow conversations – especially the confrontations – to play out in full without either occupying too much of a scene. Time and again, I was impressed by how well everything plays.

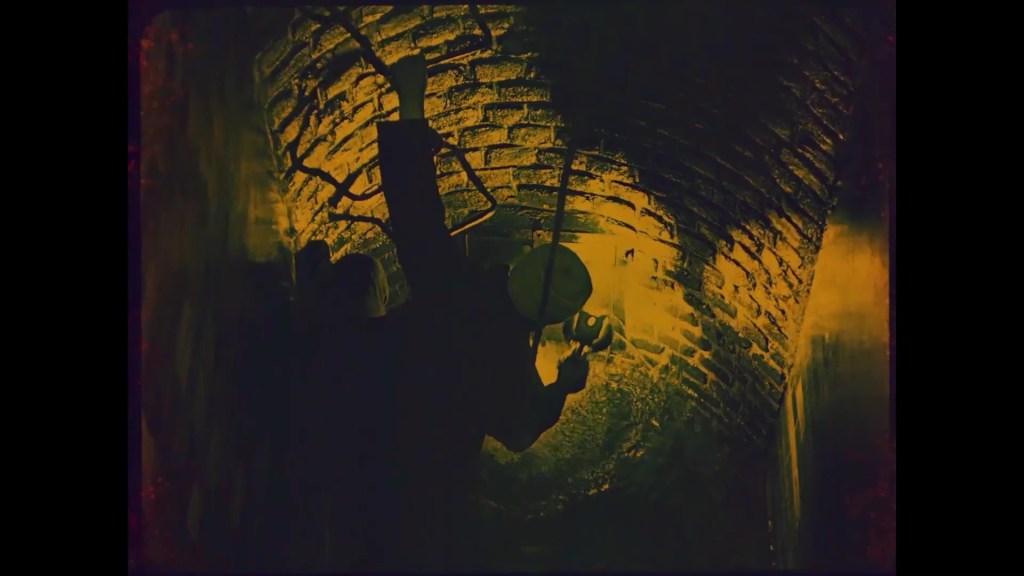

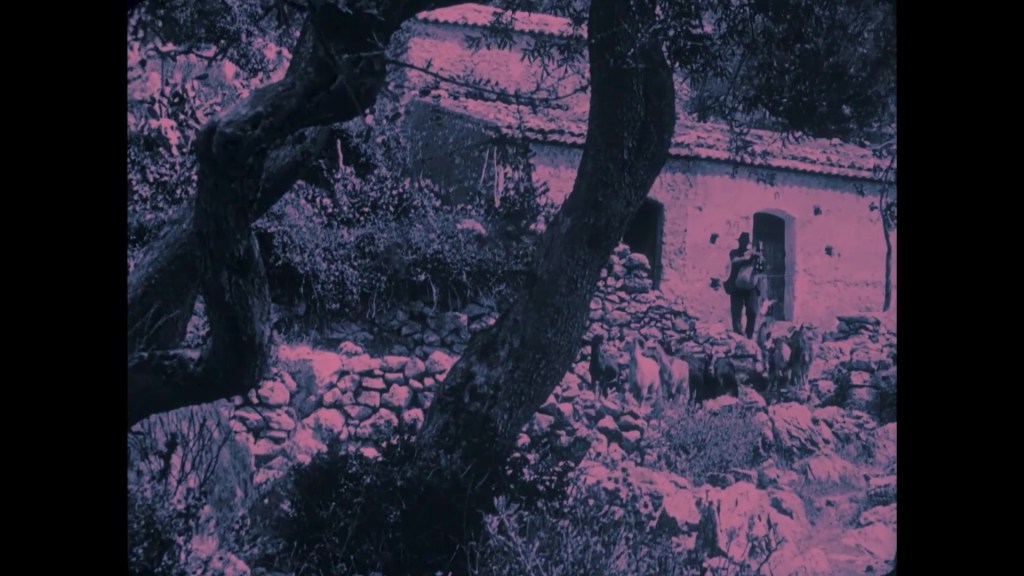

I was also utterly spellbound by how good this film looks. The photography is sumptuous, showing off the wonderfully detailed interior sets and the stunning exterior locations. The combination of tinting and toning makes the film feel almost stereoscopic. Those exteriors that show off walls of foliage, or the great vistas across the valley, are eye-poppingly beautiful to look at.

L’Ombra was restored in 2006 by the Museo Nazionale del Cinema di Torino and the Cinémathèque Royale de Belgique. (I note in passing how informative the restoration credits are at the start. As they state, this film was originally 1955m long, and this restoration is 1844m.) The copy used from the collection of the Cinémathèque Royale de Belgique reminded me, in its colours and richness, of this same institution’s restoration of Abel Gance’s Mater Dolorosa (1917). I have praised that film elsewhere for its photography and lighting, and L’Ombra feels very similar both in content and style. There is the same focus on infidelity and parenthood, the martyring of the central female protagonist, and the superbly rich, dark, carefully tinted/tone aesthetic of the film. L’Ombra gave me the same thrill, only there was something pleasingly operatic about it – a sense of grandeur that went further than Mater Dolorosa.

And it’s not just the overall feel and tone of L’Ombra that pleases. There are so many great details that tie it all together. Look how the film observes the flowers that Gerardo gives to Berta when she is first paralyzed, then the later moment when we see the empty vase – and then the moment when Berta finds a vase full of flowers in Gerardo’s studio. Or the use of the veil over the sleeping child, the way Gerardo places it gently over him, which serves as a wonderful surprise reveal for Berta. Just by itself, it’s an astonishing image. (Talking of Gance again, it reminded me of the sublime reveal of Angèle in J’accuse! (1919), when his mother suddenly draws back her cloak to reveal her unknown burden.) But the unveiling – literal and figurative – becomes a moment both delicate and devastating. Finally, there is the moment when Berta goes to the window after seeing off Elena. There is a shot of the sky, clouds unfurling with hallucinatory speed before the sun. Then we see the sunlight pour into the studio, over the reunited couple and their adopted child. The titular “shadow” is passed. It’s a gloriously literal moment of symbolic enlightenment, flooding the scene with warmth.

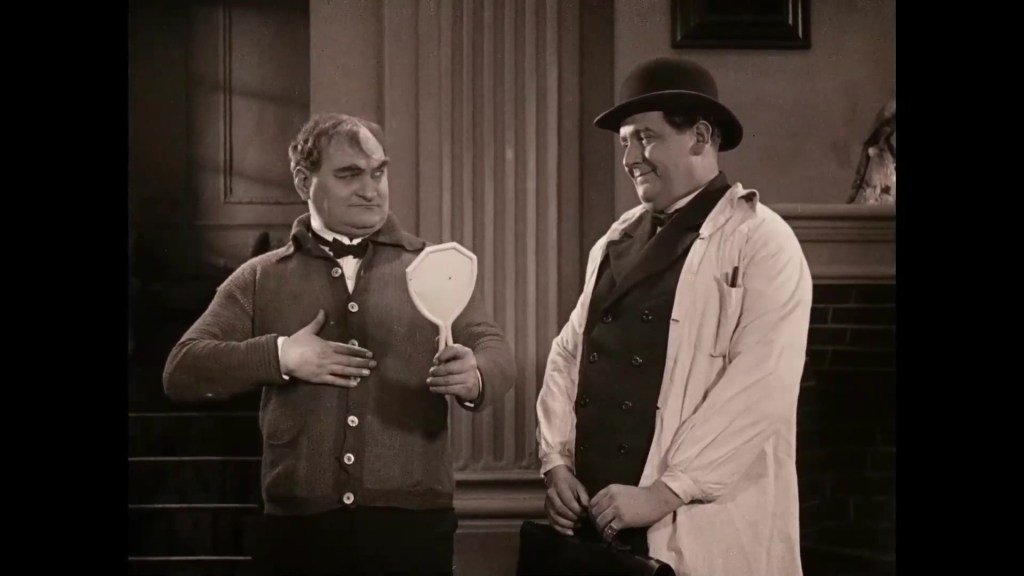

Of course, as I observed earlier this week, a film can have a meaty melodramatic plot and look sumptuous without having any emotional impact. L’Ombra does have emotional impact, and it’s the result of a great combination of its rich mise-en-scène and its central performances. Italia Almirante-Manzini is superb as Berta, carrying every moment with great conviction – and maintaining great intensity across those long, grand scenes of emotional turmoil. She makes every nuance of feeling clear without lapsing into eye-bulging hysteria. There is a grand sense of pace and rhythm that makes each scene like an operatic set piece, arias turning into duos or trios.

As Gerardo, Alberto Collo is less obviously impressive – but his character is quite deliberately the least interesting in the film. He is weak-willed, unable to act or speak honestly. The drama is absolutely centred on Berta, so Gerardo’s lesser presence on screen works. Indeed, he is also overshadowed by the wonderful performance of Liliana Ardea as Elena. The naïve girl at the start of the film exists in the shadow of Berta. Her naivety is seen in her wide-eyed embarrassment, and in her girlish delight in letting Berta guide her into society (and into marriage), and clothe her in fashionable attire. But Elena’s mannerisms soon become self-conscious. She realizes that she can charm, and this extends to deception: she casts a charm over Berta, lying to her face. (That turn of the head and glance away is meant for us to see: it’s a hint of girlishness that has assumed adult cunning.) By the end of the film, we see both her pride and her lack of maturity. Her anxious tilts of the head and darting glances remind us of the naïve figure at the start of the film, but here she’s being found out: there is nowhere to hide from Berta.

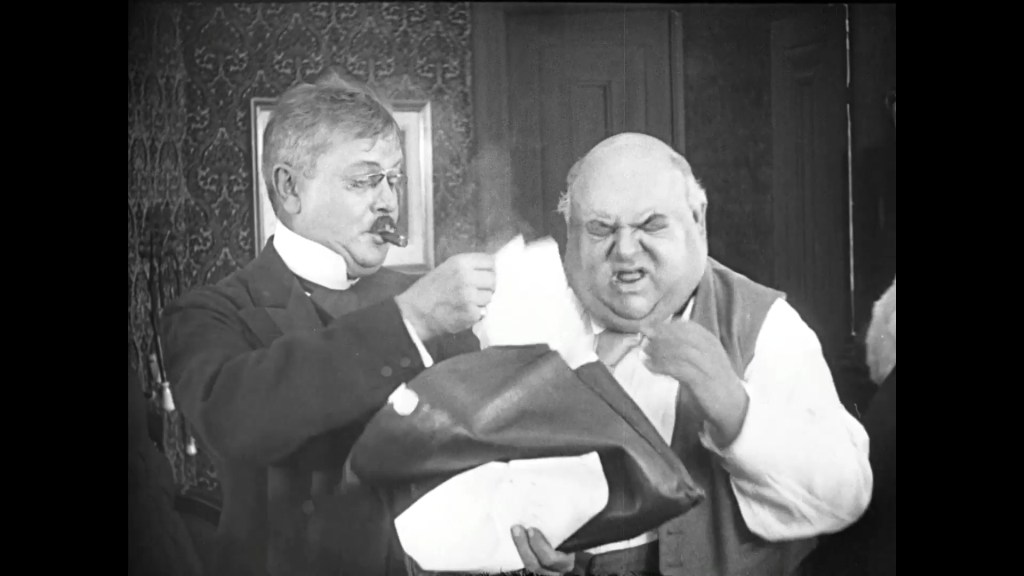

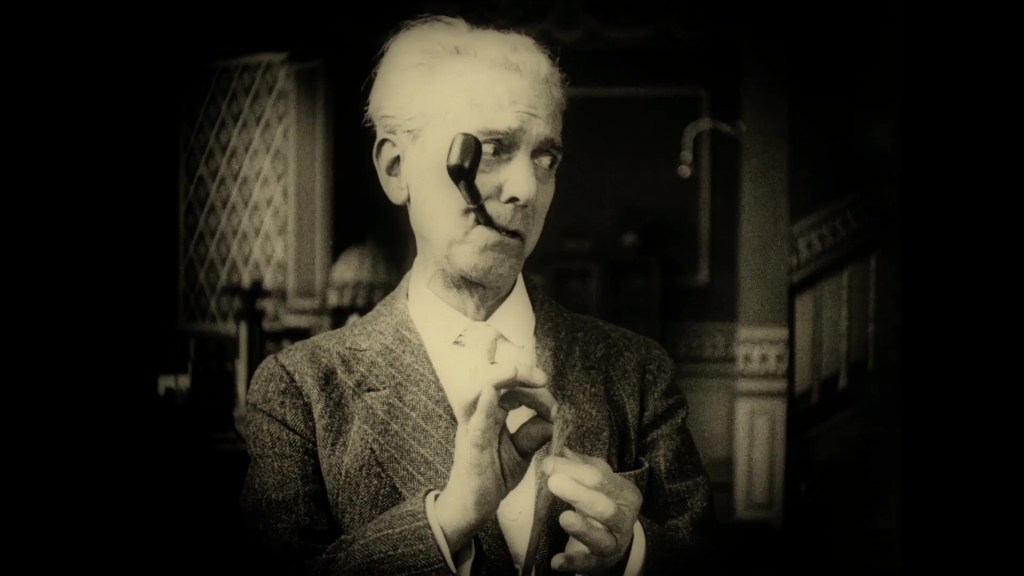

Within this gloriously melodramatic world, there is a much-needed touch of humour provided by the ironic elder figure, Michele. He’s a superb character, played with great charm and wit by Vittorio Pieri. His little nods and winks, his expressive gestures with his pipe, and – most of all – his ironic comments are wonderful. But he also gets one of the most touching moments in the film, when he realizes how Berta has been betrayed. His reaction appears to be comic, but he suddenly realizes that he is crying. He scoops a tear on his fingertip to examine it. It’s such a brilliant little moment. When the source of ironic detachment in the film starts to cry, you realize the depth of feeling in this world, and you sense the history between these old friends.

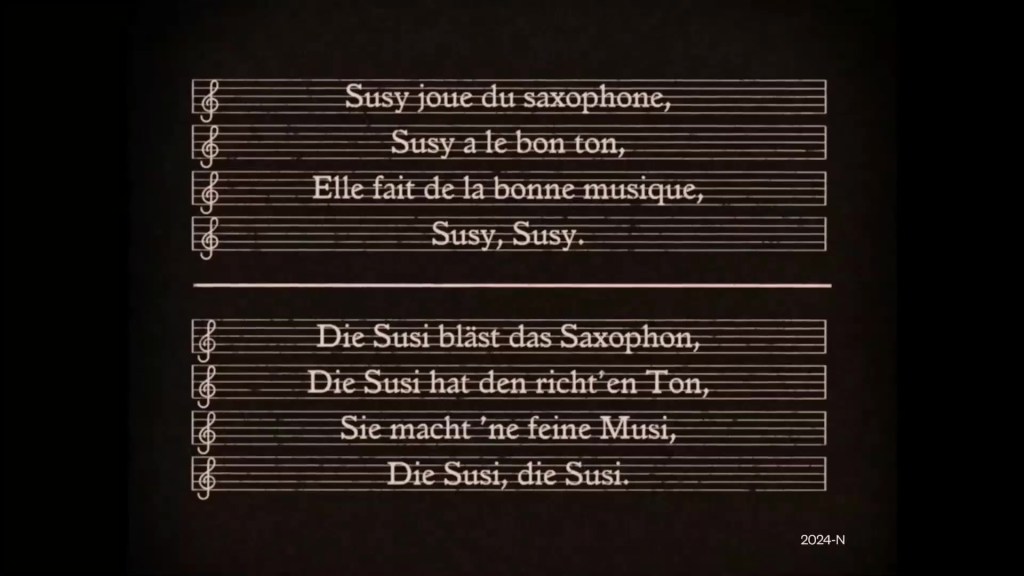

For this presentation of L’Ombra, piano music was provided by Michele Catania. His score is sumptuous, full-blooded, swoonily romantic. It captured the mood and pace of the film, following each emotional beat with great skill – spanning and typing together even the longest of melodramatic scenes. Of many moments that pleased me, I single out the scene when Berta recounts her miraculous recovery to the doctor, and the moment when she raises her arm for the first time – high enough for it to slowly and surreally appear within the frame of the mirror. The score makes this scene rapturously pleasing. So too for Berta’s first attempt to raise herself on her legs. Musical exertion matches Berta’s physical and moral exertion. After the thunderous passage of music when she stands, the music slows and quietens when she sits. It’s not just capturing the tempo of the action or its sense of movement, but the emotional sense of the scene: it’s filled with tenderness, a kind of warm glow in the satisfaction of the miracle taking place. What might easily fall headlong into bathetic parody becomes supremely pleasing and moving.

In sum, this was the best film I’ve seen so far at this year’s online Pordenone: a great melodrama, beautifully shot, superbly restored and presented. Bravo.

Paul Cuff