Long-time readers may have registered my admiration for Viennese director Hanns Schwarz, whose sumptuous Ufa production Die wunderbare Lüge der Nina Petrowna (1929) is a favourite of mine. I have a forthcoming (I hope!) article on his marvellous Ungarische Rhapsodie (1928), a film which I will also write about here sometime in the future. Neither of these films is currently available on DVD, but they are at least accessible in some form or other. (Even if one must go to Berlin, as I did recently, in order to see anything like a complete print of Ungarische Rhapsodie.) Schwarz’s other silent films are a different matter. The one I’d most like to see is Die Csardasfürstin (1927), an adaptation of Emmerich Kálmán’s delightful operetta. Alas, the only extant copy of this film is currently not able to be viewed. (For unstated reasons, presumably the lack of a safety copy, the Bundesarchiv’s 35mm print is restricted to the vaults.) I have at least been able to see Die Kleine vom Varieté (1926) at the Bundesarchiv, and this enormously enjoyable film will be the subject of another post in future weeks.

Today, however, I want to talk about the only other Schwarz silent from the late 1920s that is available to see: Petronella (1927). I find that I have hardly mentioned this production in my writing on Schwarz, not because it is less interesting, but because it seems to stand out among his films of this period. My interest has primarily been on Schwarz’s work for Ufa, especially his operetta films leading up to the transition to sound. Petronella may have been made with Ufa’s involvement, and shot partially in Ufa’s studios, but it was a co-production with Helvetia-Film. Adapted from a Swiss novel, recreating an important period in Swiss history (and Swiss national identity), its exteriors shot on location in Switzerland, and premiered in Bern in November 1927, Petronella is a very Swiss film. Happily, and rather appropriately given its subject, Petronella has recently been restored by the good people of the Cinémathèque Suisse, to whom I am very grateful for allowing me to access a copy of the film. Though this production has been the subject of one or two pieces (exclusively devoted to Swiss film history), I came to Petronella with very little idea of what it would be like – or how it might compare to Schwarz’s other work. Today’s piece emerges from my growing fascination with this unjustly little-known director, whose films continually have the capacity to surprise…

Based on Johannes Jegerlehner’s novel of the same name (1912), Petronella is set during the Napoleonic Wars. In 1801, the inhabitants of Brunegg are fighting the advancing French army. The pride of their village, the church bell known as “Petronella”, is ordered by Father Imboden (Theodor Loos) to be taken away and hidden for safety – but it is lost in a crevasse en route. Meanwhile, Gaberell Schwiek (Ernst Rückert) is mortally wounded in the battle. His last wish is for his new tavern to be completed by his young wife Pia (Maly Delschaft). Time passes, and the village mourns the misfortune of the missing “Petronella”. Pia’s new tavern is built – but she will need a license from the local council to open for business. Since the death of her husband, Pia has attracted two rivals for her hand: one of her late husband’s friends, whom she loves, Josmarie Seiler (Wilhelm Dieterle), and the wealthy, older landowner Fridolin Bortis (Oskar Homolka), whom she despises. Spurned by Pia and jealous of Josmarie, Fridolin goes to the council and denounces Pia as a woman of ill-repute – thus scuppering the approval of her license. However, Father Imboden intervenes and the license is duly granted. The rivalry between Josmarie and Fridolin reaches tipping point, and in a fight between the two Fridolin is killed. As punishment, Josmarie is exiled from the land. The misfortunes of the village continue, as there is a deadly illness at large. A local “witch”, Tschäderli (Frida Richard), is blamed and persecuted by the villagers. Further misfortune strikes when the church silver is stolen by Father Imboden’s ex-convict brother (Fritz Kampers). Realizing the truth, the priest confronts his brother – and accidentally kills him. Distraught by the deaths of Tschäderli and his brother, Father Imboden enters a monastery. Finally, Josmarie finds the “Petronella” and returns to Brunegg, where he is absolved of his sins and can marry Pia. ENDE.

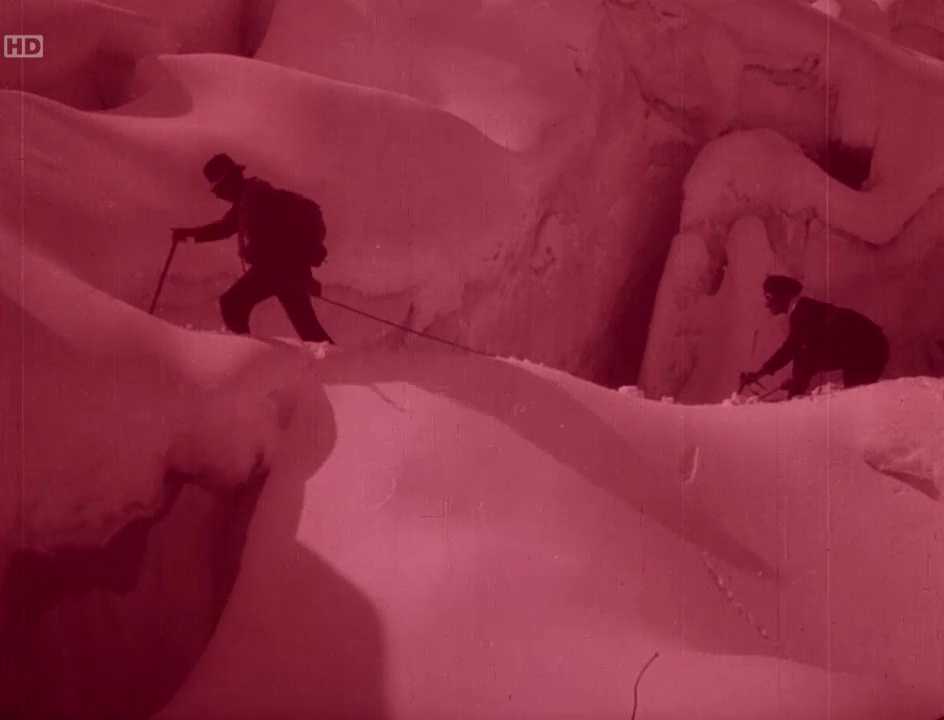

Petronella is an impressive film. The cast is strong, the performances realistic, and the setting and staging often very striking. Most obviously, the film’s prelude introduces us to the village and the surrounding spaces through the drama of a battle between French soldiers and Swiss locals. Schwarz uses the rocks, streams, and slopes of the valley to great effect. The camera peers down over successive ranks of fighters, or glances up at groups swarming over the precipitous ridges. Clouds of smoke disguise and reveal the landscape, just as the advance and retreat of figures show the difficulty of traversing it. It’s a great way to start the film.

I described this as “a very Swiss” film, and throughout there is a clear effort to show off the real landscapes and buildings of the region. (I have read conflicting reports as to where exactly it was shot. Though Brunegg is a real municipality in the canton of Aargau, the production seemingly used multiple exteriors elsewhere.) The film also engages with local (traditional) dress and culture, most obviously in the fight between the two cows that will decide who gets to marry Pia. The tone here, and throughout, is often quite broad. This is not only an outdoorsy film, rooted in the local/national/traditional, but a film that invites a popular audience. The drama and its telling are clear and free of fussiness. I suppose this is a nice way of saying that Petronella struck me as less visually inventive as some of Schwarz’s other films, especially those shot by Carl Hoffmann. The cameraman for Petronella was Alfred Hansen, who shot five films with Ernst Lubitsch in the 1910s, including Carmen (1918). If these productions link Hansen to one of the great directors of the era (and of all time!), his involvement was with films that are not primarily admired for the elaborateness of their photography.

I realize that I am adding quite a few caveats here, but I don’t mean to lessen the achievements of Petronella. Though it offers a broad, popular, unfussy treatment of its material, there are lots of moments that stand out for their subtlety and effectiveness. The end of the prologue is very striking. Here, Gaberell lies wounded in bed. To aid his recovery, Tschäderli – the local “healer” – is called. She is initially treated as a bit of a joke, and her actions are cause for some comedic touches. She forbids Gaberell fresh air and banishes Pia’s pet black cat. Josmarie cautiously picks up the cat and drops it out of the window in a scene that is so odd that it becomes funny. (It is surely played for a laugh.) But things swiftly turn serious. When Tschäderli leaves, she promises Pia that Gaberell will be up and well within two days; if he isn’t, it will be cause of some malign influence wielded by the black cat. Pia goes about her business, but on returning from fetching water she sees the black cat sneaking back out of the house. It’s a disconcerting moment, since we last saw the animal being ejected. It has clearly returned, and is now making its getaway. Since the earlier moment of the cat being dropped from the window was treated for comedy, Pia’s terrified reaction here comes as a shock. Clearly, these characters take such superstition seriously.

Pia rushes back to the house. She pauses on the threshold and, through the open door behind her, we see the snowcapped mountains. It grounds this moment – a pause before a death – in the reality of the landscape. There is also a sense of release outside the confines of the home, of a wider context to life within the home (or death within the home). Only now does Schwarz cut to a view of the bed. We are placed at a distance, like Pia, unable to intervene. The early interior scenes in this space played out in medium and close shots, and now we find ourselves looking at it in a new, less familiar way. Framed by the dark walls of the inner doorway, we see Gaberell lift and then drop his arm – as if reaching for help, or raising an alarm. Seen from a distance, through the doorway, this moment of death is rendered stranger and more sudden by this framing and distance. The oddness of how we see Gaberell’s death seems to vindicate Tschäderli’s warning. There is something unexpected, sinister even, in this domestic space. (Later in the film, there are many more moments where important gestures/actions are seen through the windows of the house – including Josmarie’s return to Pia at the end of the film, as though he has now returned to the space – literal and symbolic – vacated by Gaberell.)

At this point, I should say that I tracked down the original censorship report from 11 October 1927, a month before the film’s German premiere in Berlin (a week after the Swiss premiere in Bern). This was very interesting, as the intertitles it lists are different in order and in number from the those preserved in the Cinémathèque Suisse restoration of Petronella. The Berlin censor’s list of titles, together with its notes about cuts, also helps flesh-out two rather complex, and rather subtle, subplots that the film lets bubble away without quite resolving them.

The first is that of Tschäderli, whose first scene I discussed above. This character returns later in the film, when the village is beset by illness. In the 2024 restoration, we see Tschäderli blamed by the locals for the curse upon Brunegg – she is spat at and ushered from the village. But this is the last time we see her in the film. The censorship report includes extra intertitles here, indicating that the locals chase Tschäderli to her hut, accuse her of various forms of witchcraft, and then attack her. She is defended by the priest, but the locals taunt him that he isn’t trustworthy since his brother is a convict. Though the censorship report from October 1927 doesn’t offer a description of what happens on screen here, a second censorship report (for a regional release of the film in Baden in December 1928) does describe the action. According to this, Tschäderli’s hut “is set on fire, and she herself is finally killed while fleeing into the mountains”. This deadly encounter immediately presages the return of Father Imboden’s brother, his theft of the church silver, and his own death at the hands of Imboden.

Talking of this character, the censorship reports are also important in revealing a detail lost from the surviving version of the film. This relates to the second subplot I mentioned earlier. When Father Imboden intervenes to win Pia her licence, she is overjoyed and goes to embrace him. Realizing this might be overly familiar for a priest, she withdraws. However, Imboden reaches for her hands and begins stroking them – just as he fixes her with an odd expression. Pia goes to get him the first glass of wine she is now legally allowed to serve. She hands it to him, and Schwarz frames the priest holding the glass in a medium close-up. An iris subtly closes in to isolate this vessel, and then a dissolve transforms it into a chalice; the iris now expands and reveals that this second vessel is being held by Imboden at mass. It’s a surprisingly sacrilegious moment, affirming the crossing of professional and personal boundaries by the priest.

Before the film was censored, this sequence originally had an even more startling sequel. Imboden is leading mass. Standing before the altar, he glances up to the statue of the Virgin Mary. In the words of the Berlin censor: “the face of […] Pia appears to the priest instead of the face of a Madonna; she nods and smiles. This [shot] appears twice.” This startling interruption makes explicit what was going on in the earlier scene. It also explains the tortured, surprised reaction of the priest, filmed from a high angle: it’s his vision (and repressed love for Pia) as much the Madonna who looks down on him. The punch of this moment is rather lost without the close-ups of Pia, long since excised by the censors in 1927.

Even if the film’s current form makes these elements less effective (or even visible), they indicate how Petronella complicates its depiction of place and people. It may be a genre film, but it does interesting things with its story. In this respect, Petronella makes an interesting companion piece to later German films depicting the same period and (broader) region. Most obviously, Luis Trenker made two films dealing with Tyrolean resistance to the French: Der Rebell (1932) and Der Feuerteufel (1940). Though the Tyrolean revolt of 1809 took place in what was then the Holy Roman Empire and is now northern Italy, the story and landscape make Trenker’s two historical dramas very similar to Petronella. Yet the tone and treatment are very different. Trenker is more interested in the male hero (played, naturally, by Trenker himself) and the martial aspect of resistance to foreign occupation.

The 1932 film feels very much like (and was taken at the time to be) a statement against French occupation of German territory in the wake of the Great War. It ends with the martyrdom of Trenker’s titular rebel, shot by firing squad – exactly the kind of heroic national figure that attracted the Nazis. But if the Nazis loved Der Rebell, they were much more cautious towards Der Feuerteufel. By 1940, the image of popular resistance to an invading force looked too much like sympathy for Poland (or Czechoslovakia, or France, or anywhere else the Germans had invaded).

However complex these contexts, both of Trenker’s films stand in contrast to Schwarz’s Petronella. It seems to me that the latter has a much more complex and ambiguous viewpoint to its subject and its “national” community. For a start, the war against the invaders is the setting but (I would argue) not the subject of Petronella.Unlike Der Rebell, which continually depicts acts of violent resistance, and ends with a big battle sequence, Schwarz’s film gets the fighting with French troops out the way fairly quickly at the start of the drama. Though the battle scenes are extremely impressive, they act only as the prelude to the real drama. Petronella is primarily the story of a woman’s struggle to gain independence from intrusive male power (the rich landowner, the council) – and from intrusive male desire (the landowner, even the priest).

The local population is not merely a united, heroic force of resistance to foreign influence. Rather, it is a complex and often parochial society. Superstition is rife, not merely in the figure of Tschäderli but in those of her accusers (especially in the lost scenes of her persecution and death). There are plenty of tensions here, and the view that Brunegg is somehow cursed by the bell’s absence smacks of an era that seems older than the dawn of the nineteenth century. When the local elders announce the “indulgence” (i.e. wiping clean of sin) for anyone who recovers the bell, their notice proclaims that among their misfortunes is the arrival of “Seuchen”, which might be translated as “epidemics” but also as “plagues” – a rather medieval way of looking at the world. (Indeed, it is worth noting here that one of the reasons that the Tyrol rebelled against French occupation in 1809 was the order that the locals be inoculated against smallpox.)

It is the symbol of the bell, with its feminine name “Petronella”, that brings the community together. The rediscovery of the bell enables forgiveness and reconciliation – and forgetting. But how convincing is this ending? The German censors of 1927-28 were a little concerned at the film’s depiction of the “indulgence” issued to resolve the drama, and whether it too easily gave exemption to Josmarie not merely for his legal crime but for his sins. What was still a potentially awkward question of civic and religious law in the 1920s is less so today. More intriguing is how we are to take the broader “indulgence” of the community itself. How much of what we have seen is to be “indulged”, and by what authority? Given that we have seen superstition, manipulation, deceit, and violence at work in Brunegg, there is surely a note of doubt hanging over the ending. Beyond the loving couple, how comforted are we that all is well and stable in this community?

Thinking about how local or national identity plays out in Petronella, it is worth noting the fact that the screenplay was co-written by Schwarz and Max Jungk, both Jewish émigrés from the former Austria-Hungary. (Schwarz was born in Vienna; Jungk in Myslkovice (now in the Czech Republic).) Jungk had co-written two of Schwarz’s earliest films, Nanon (1924) and Die Stimme des Herzens (1924), neither of which I have been able to see. (Nanon, at least, survives, but the only copy lies in an archive beyond the bounds of my current travel budget!) Whether or not there is something of an outsider’s eye at work in Petronella, the involvement of émigré artists indicates the complex context in which to see this ostensibly Swiss production. In this light, Petronella might be seen as a film about belonging and expulsion. Tschäderli and Josmarie are expelled from the land, just as Father Imboden exiles himself to a monastery. (One might also add Pia’s unfortunate black cat to this list.) Imboden seeks to send his brother away from Brunegg, an act which ends in the latter’s death; the locals force Tschäderli to flee, an act which ends in her death. Only one exile returns alive to be forgiven and reintegrated: Josmarie. It feels inevitable that I must mention the fate of Schwarz and Jungk: both men would be forced to flee Germany in 1933; neither returned.

I have written this piece on Petronella because the film has lingered in my mind in the days since I saw it. I admit that I was surprised by how different it seemed from other Schwarz films. Less obviously stylish, I initially found it less engaging – and less moving – than his contemporary work. But the more I think about it, the more it seems quietly innovative. While exhibiting the trappings of many “mountain films”, as well as the historical drama, Petronella feels a little peculiar. It is not a Trenker-style (or Riefenstahl-style) mountain film about conquering peaks, heroism, and death-defying stunts. Nor does it offer a simplistic us v. them narrative of a historical-national drama. The war quickly recedes into the background, and its consequences exacerbate the various personal and social tensions in the village. As I have tried to indicate, Petronella is rather more complex and curious than its generic parameters suggest. I’d love to see how it plays before an audience, especially with a good score that brought out the tensions in the drama. Hanns Schwarz, you continue to intrigue.

Paul Cuff

My great thanks to the Cinémathèque Suisse, especially Saskia Bonfils, for allowing me to access their restoration of Petronella.