Day 4 takes us back to Germany and the company of Harry Piel. This time, we’re following the adventures of the director-as-star himself on screen. He starred as “Harry Peel” in several films, the first of which was Der große Unbekannte (1919). He returned to the character in Das schwarze Kuvert (1922), the first of a trilogy of films with recurring characters and overlapping narrative. As Hemma Marlene Prainsack and Andreas Thein explain in the festival catalogue:

In the 1922-23 season, Piel reappeared as Peel in […] Rivalen (working title Der gläserne Käfig) and Der letzte Kampf (also known as Der Elektromensch), all based on scripts by Alfred Zeisler and Victor Abel. Here’s where things get complicated. While making Das schwarze Kuvert, his company declared bankruptcy, and no ads, articles, or documents position the film as the initial offering in a series. We know from the German programme booklet that the character names in Das schwarze Kuvert differ from those in Rivalen, but in the sole surviving print of Rivalen, from its Russian release, not only are the character names identical, including for minor roles, but there are two direct references to Das schwarze Kuvert: the dogs Greif and Caesar reappear in Harry’s boudoir, and when his beloved gazes into her mirror, she sees Harry exactly as he appears in the earlier film. In addition, the Russian version of Das schwarze Kuvert starts with a title card clearly stating it’s ‘Part 1’, and ends with ‘to be continued’. (116-18)

In Das schwarze Kuvert, “Peel loses his money in a London banking crisis and moves to the Alps; there he falls for a rich industrialist’s daughter who’s subsequently kidnapped by order of a nefarious physicist” (ibid.). Though he rescues her before the end of the film, at the start of the second film—today’s feature—we find our character with plenty of unresolved crises. I provide all the above info because the oddness of the film that follows can only by explained by some reference to what came before (and what was meant to follow). The London setting of the first film also helps explain the anglophone names of all the characters—though doesn’t clarify exactly where the sequel is set…

Rivalen (1923; Ger.; Harry Piel).

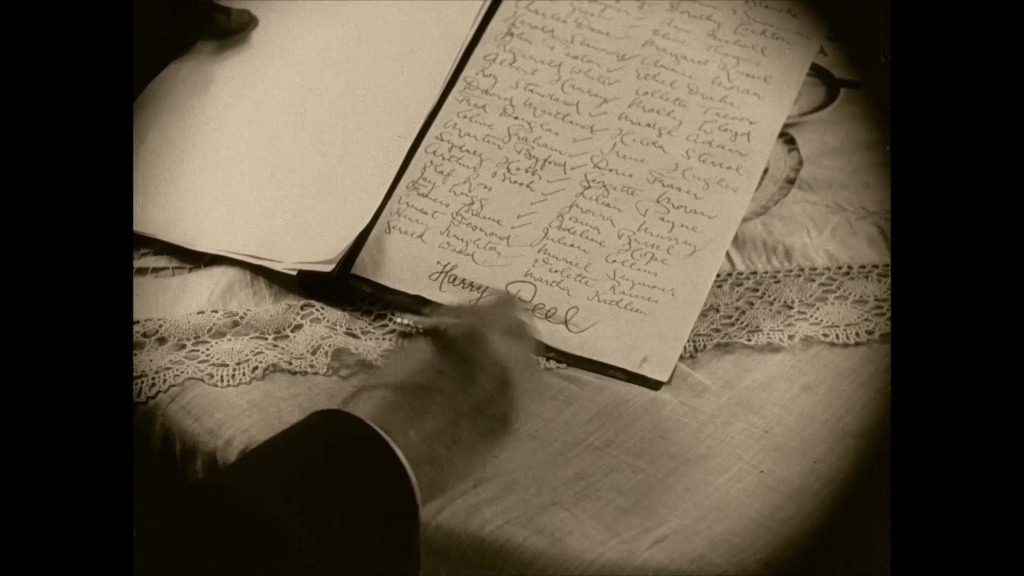

The film credits itself being presented into “seven adventurous acts”. I’m sold. Bring them on… But before they even begin, we are given a star portrait of the director Harry Piel as his screen avatar “Harry Peel”. Piel looks languidly toward the camera, though his pose suggests he is halfway between actions. It’s a pose that will soon end. This man will soon get to business…

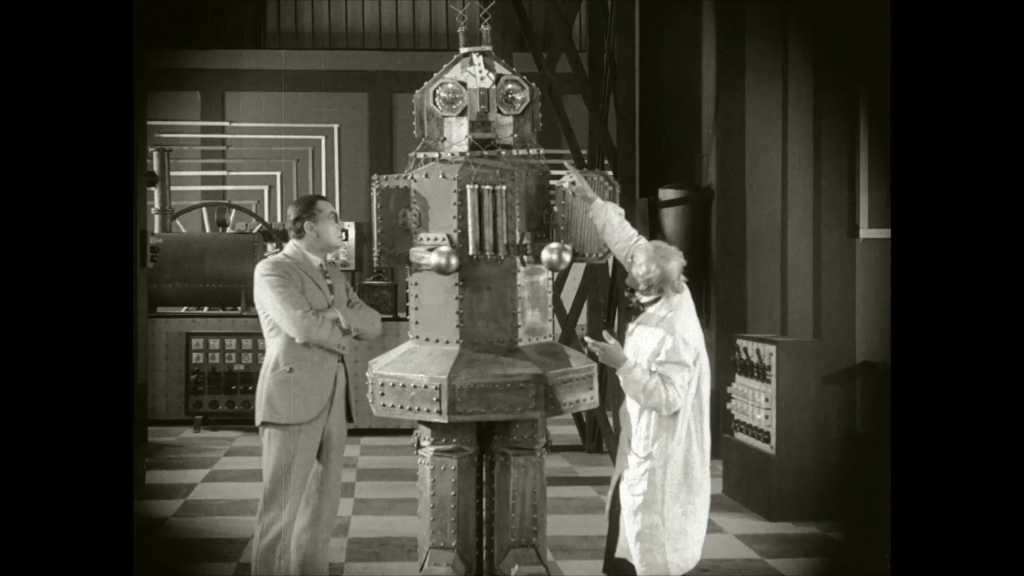

Act 1. The Evans electrical plant. Evans’s rivalry with the evil Ravello, both over their electrical inventions and over Evans’ daughter Evelyn, whom Ravello wishes to marry. Here is Ravello, in a sinister cap, smoking moodily. And here is Julietta, a former dancer and Ravello’s agent/companion. Contrast Julietta’s swarthy good looks with Evelyn’s fluffy, curly blondeness. She looks absurdly pampered. (And already, you have the sense that the film is here to have fun and entertain rather than create real characterization or suspense.) A fancy-dress party at Evans’s. Evans doesn’t want Harry Peel at the ball. Evelyn does. She writes his name on the guest list. He crosses it out. Meet Chilton, one of Ravello’s stooges. And in Ravello’s lair, a posse of uniformed footmen. Chilton’s lab, like a mainstream version of Jaque-Catelain’s lab in L’Inhumaine (1924). Only here the centrepiece is a delightfully silly robot with cute, illuminated eyes and a kind of metallic skirt. “He walks!” they cry, as the seven-foot robot lurches slowly forward. Chilton spots an ad for the masked ball, it’s theme: “A Party in Hell”.

Act 2. The party. Elsewhere in town, at the Trocadero, Julietta awaits Ravello—but he has spurned her for a “conference”. In fact, his masked gang are on the move to the Evans’s ball. They rob guests Hoppel and Poppel (both suitors of Evelyn) of their invitations, so Ravello gain access. (And as Ravello arrives, Julietta is spying on him.) The ball. A marvellous set. A kind of comic version of the sacrificial temple scene in Cabiria (1914), complete with guests in masks and horns. Cue comic japes with Hoppel and Poppel, dashings back and forth—into the “blue room” (tinted thus), where Ravello threatens Evelyn, only for Harry to rescue her via a series of hazardous leaps and bounds, followed by a lasso. Ravello foiled and ejected, Julietta once more observes the goings on…

Act 3. While the party carries on with devilish dancing, Julietta appears and demands an audience with Evelyn. (But she demands this from Hoppel and Poppel, who by now are delightfully drunk.) Chez Ravello, Chilton is scheming. And soon the party is surrounded by sinister goings-on: Ravello’s gang are dragging something, sawing something, loading something. The silhouette precedes the surprise delivery: it’s the robot! The guests flee, but then Evans steps forward. He clutches at the robot’s arms—and is electrocuted! Harry steps forward, only to see Evelyn being approached by Ravello’s agents. (Should this all sound delightful, it is—but a part of me is already longing for the danger to be less silly, the villains more villainous, the hero less one-dimensional…)

Act 4. Julietta wishes to aid Evelyn. But meanwhile, the robot grows supercharged, and the entire dancehall is a nest of lightning bolts as the robot wanders free. Partygoers flee, as a fire begins to burn. Harry sets off in pursuit of Evelyn in the car. Cue high-speed car chase, Hoppel and Poppel bungling alongside. A retractable bridge—and Harry’s car plunges into a lake! But he escapes and makes his way to Ravello’s house. Here, he sees Ravello takes charge of the wrapped-up body of… Julietta! Ravello says she will never again leave the house without his permission. Harry is captured changing into some dry clothes. He escapes and finds Julietta, with whom he makes a break for it. Cue: secret doors, amazing leaps, fistfights, chair fights, trapdoors… (Yes, all easily executed; no, the danger is swiftly thwarted.)

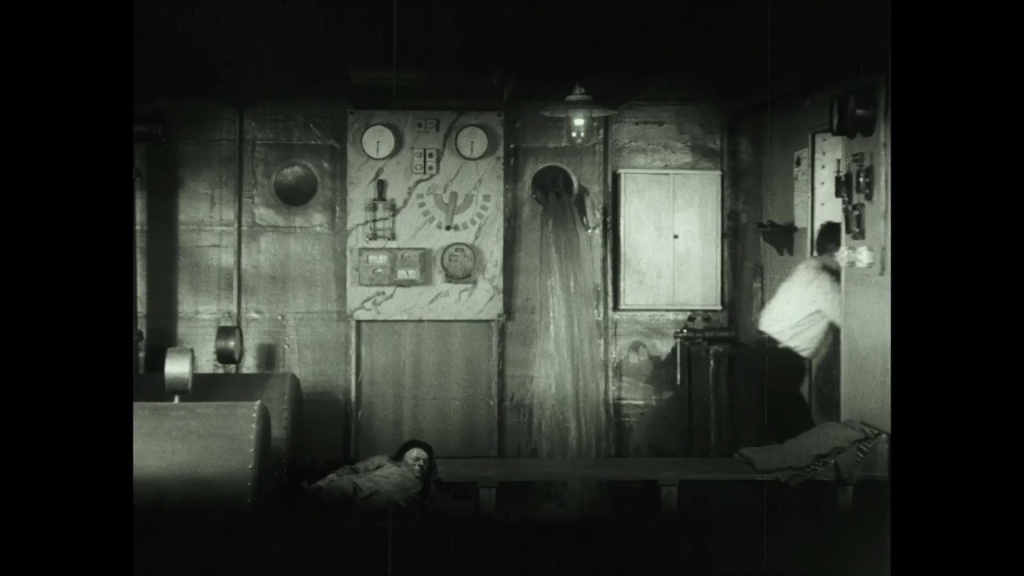

Act 5. Juletta is captured and Harry is taken aboard Ravello’s secret weapon: a submarine! Eveyln, meanwhile, is safe at home. But Harry awakes to find himself in the submarine. “You weren’t expecting this surprise, were you?” says Ravello. No, and nor was I. (Lovely shots of the moonlit lake make me long for a world where any of the action really mattered, or one where the outside world was allowed a greater role on screen.) Julietta is guarded by Artos, but Artos is in league with Julietta—and as soon as Ravello leaves, takes her outside (apparently for a romantic supper). Now Harry plots his escape—glimpsing occasionally into the camera as he cuts the ropes around his wrists and ankles. He smashes a window, and the water starts to pour in. He fights and bests a dozen submariners (of couse), then runs to freedom. Meanwhile Hoppel (or is it Poppel?) takes Evelyn for a drive. Mid-escape, Harry is surprised by a group of boulders that come alive and capture him again! (This is the apex of the film’s silliness, the gang of boulders looking like Monty Python’s vicious hang of Keep Left signs.) Harry is lowered in a glass cage into the lake (and below the surface, we get a cute—but unconvincing—glimpse of a studio seabed with glass tank placed before the camera to provide live fish and bubbles). Julietta and Artos observe the strange goings on…

Act 6. Hoppel (or is it Poppel?) and Evelyn arrive at the lakeside and see Harry’s smashed car in the water. They encounter Artos and Julietta, but are observed by Ravello, who takes Julietta into the submarine. From the porthole she sees Harry in his submerged cage. “As soon as you agree to marry me, Harry Peel will be set free.” Dastardly! The comic sailors guarding the breathing apparatus of Harry’s cage go off to meet some other comic sailors, leaving Harry to suffocate. They arrive back just in time to dredge him up.

Act 7. Retrieved from the lake, Harry dunks his erstwhile captures and swiftly scales a cliff. He steals a horse from the bad guy’s hideout and sets off. He vaults through Evans’s window and finds Evans and an explanatory note from Evelyn about the forced marriage to Evans. Another high-speed car ride—but is it too late? (Hoppel and Poppel, meanwhile, wander about with bouquets, each hoping to find and marry Evelyn. Their plotline grows evermore irrelevant.) Harry rescues Evelyn, but Ravello escapes. The bribed priest tells them that the marriage is legally binding. How to get Ravello to give up his bride? Evans wants to find a way, Eveyln wants to find a way, Harry wants to find a way. But… “Ende”! Noooo!! “The story continues in the next Harry Peel film: Der letzte Kampf”. Damnation! An end that isn’t an end…

Day 4: Summary

Well, what can I say? Rivalen was a colossally silly film. A kind of supercharged serial, only with far more jokes and much less real suspense. I did enjoy it, but on an entirely superficial level. Gabriel Thibaudeau provided enthused accompaniment on the piano, but what kind of tone does the film expect from its score? It is adventure, it is comedy, it is episodic… it is oddly meandering. The problem I had is that I simply lost any sense of dramatic tension, no matter how far the film ramped-up the thrills. It all felt a bit… safe. I love a good serial, but I’d prefer one in which the villains were more threatening (more capable of real and actual damage to life and limb)—and the heroes had more of a personality, even if this were mere obsessiveness. Harry Piel is certainly a committed screen presence, but I’d be hard pressed to say anything about his character. He runs about, he leaps, he dives, he can fight. But there’s nothing more to him than the dash needed to overcome various obstacles. Even his supposed love interest in Evelyn is unconvincing on both sides. The film isn’t quite funny enough to be a comedy with action, nor is the action sophisticated or threatening enough to be an action with comedy.

Audiences at the live Pordenone will get much more Piel than us online folk: live, there are multiple Piel films from across his career. Online, there are the three I’ve covered so far. Rivalen is closer to Das Abenteuer eines Journalisten than to Das Rollende Hotel, but I still much preferred the 1914 film to either of the later ones. It had more of a sense of the real world, and more of a sense of danger and threat. But wouldn’t I want to see the sequel to Rivalen? Well… I suppose so. But only if Der letzte Kampf developed the characters or strengthened the drama presented in Rivalen.

All that said, I repeat what I said yesterday: that seeing a film like Rivalen is one of the great strengths of a festival. Piel shows us a different side to popular German cinema, a more boisterous, outdoorsy, silly, playful cinema than perhaps we are used to. In this sense, I am indeed very glad to have seen Rivalen and the earlier Piel films. I have a sense of him both as star and director, and I would genuinely be curious to see what else he did. If nothing else, Piel proves what novelties lie outside our experience of film history. We should hope to find more like him.

Paul Cuff