Day 2 sees us in Germany. In the 1910s, we’re adventuring via every possible means of transport with daredevil director Harry Piel. And in the 1920s, we’re climbing mountains to meet our destiny with Dr Arnold Fanck…

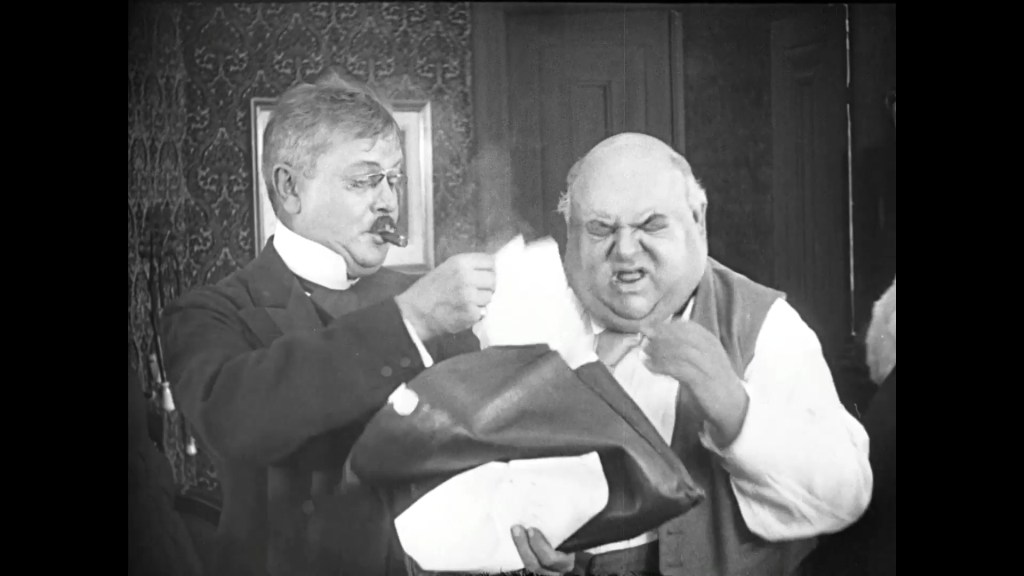

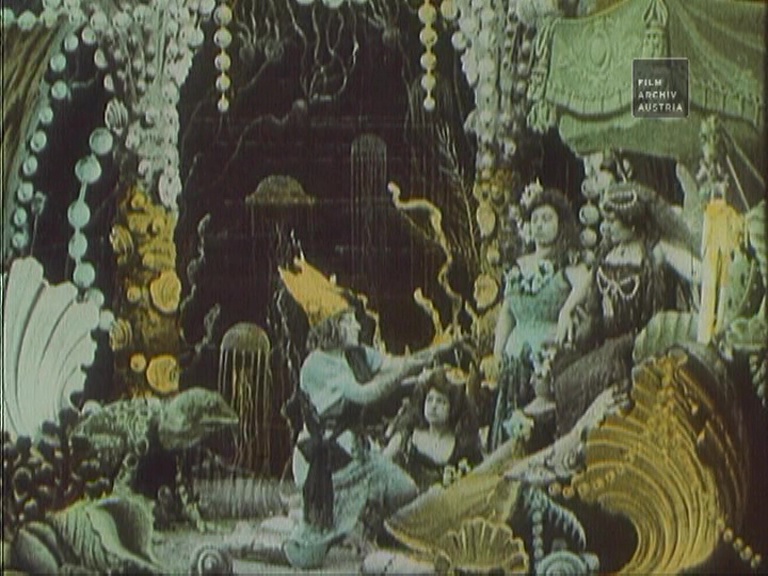

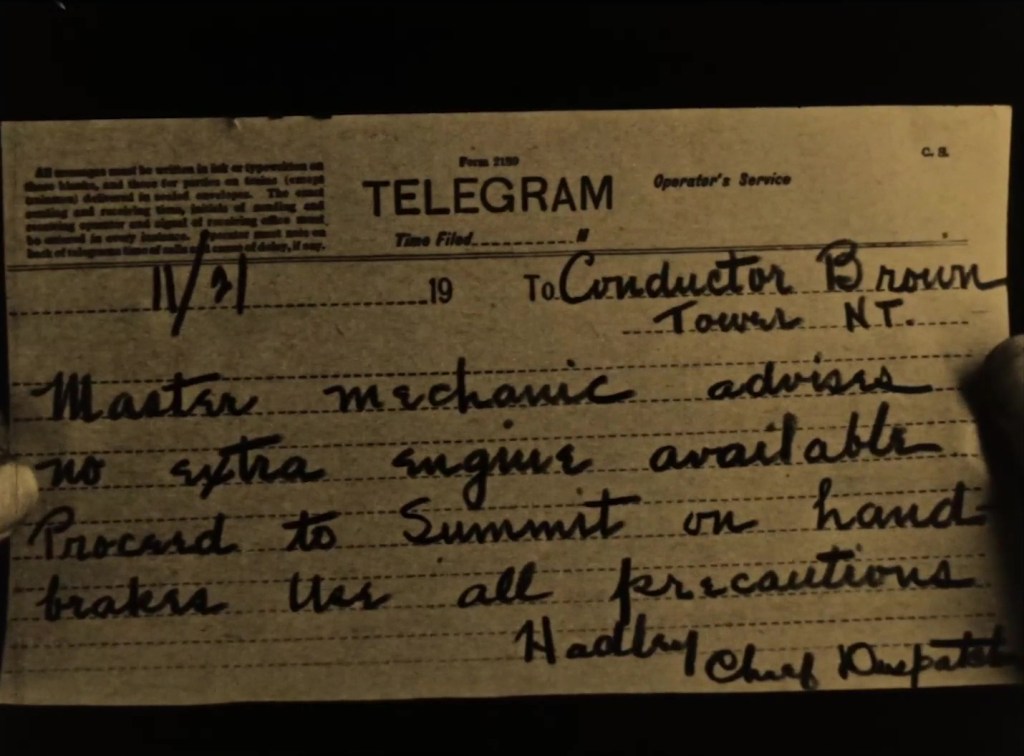

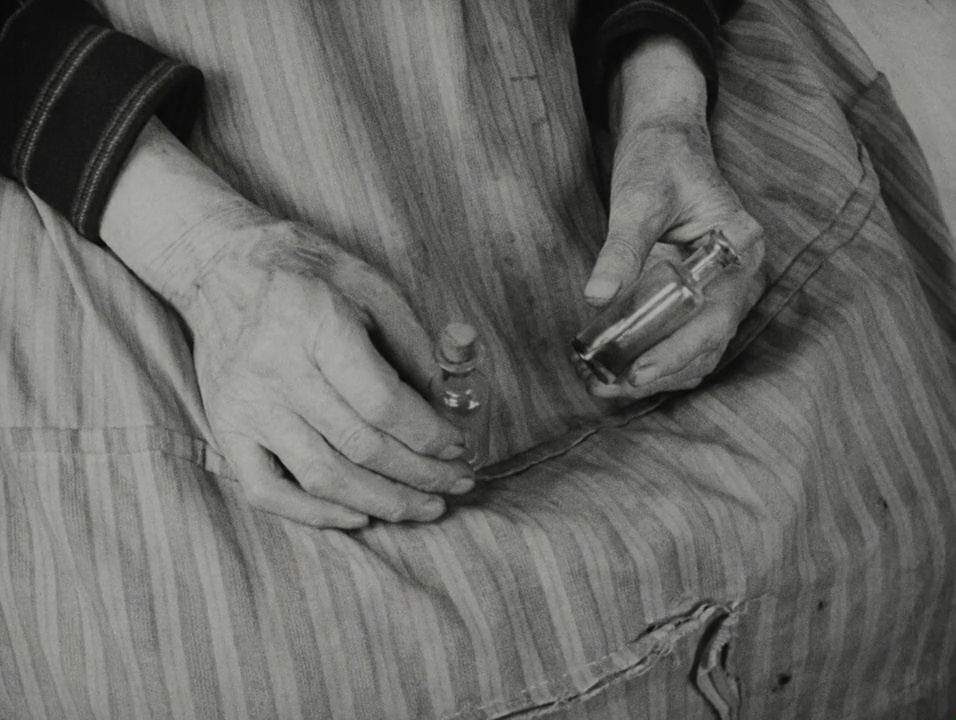

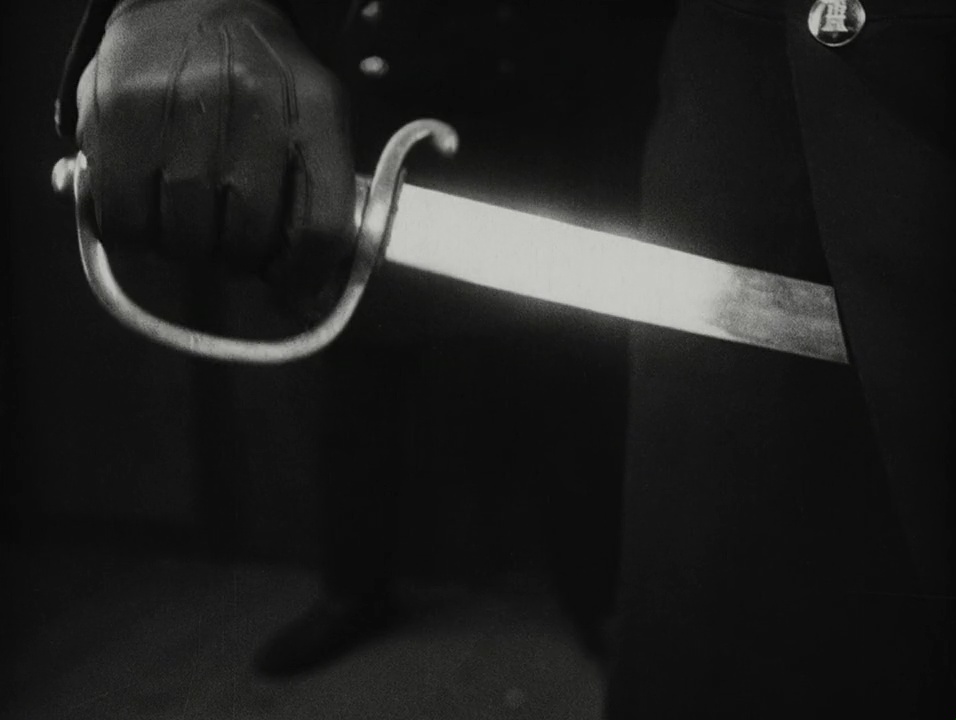

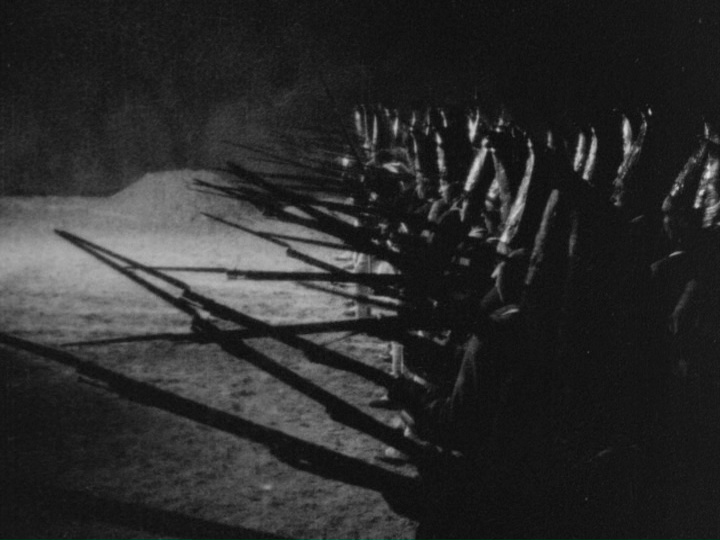

Das Abenteuer eines Journalisten (1914; Ger.; Harry Piel). Professor Cleavaers has invented a wireless detonation process for the navy. But he is more concerned about his daughter Evelyn’s romance with the journalist Harrison. Only when Harrison has a more important position in life will the scientist give him his daughter’s hand in marriage. But what Cleavaers should be more worried about is the “Medusa Society”, one of whom—Baxter—is disguised as a gardener in his employ. Baxter tries to glean his master’s secret, reporting back to the “Medusa Society” in an insalubrious tavern. They wish to win a contract from the Ministry of the Navy, so plan to steal Cleavaers’ work. The gang are all wide-brimmed hats, long coats, long dark beards. The gang kidnap the professor and steal the prototype for the detonator, as well as setting an accidental fire in his laboratory. While the professor stumbles about in the gang’s underground lair, Harrison promises Evelyn he will investigate her father’s disappearance. He finds him pretty quicky, dodging mantraps and trapdoors, pistols, bombs etc. (At one point, he foils the gang with a small bottle of petrol that he happens to carry with him. Very convenient!)

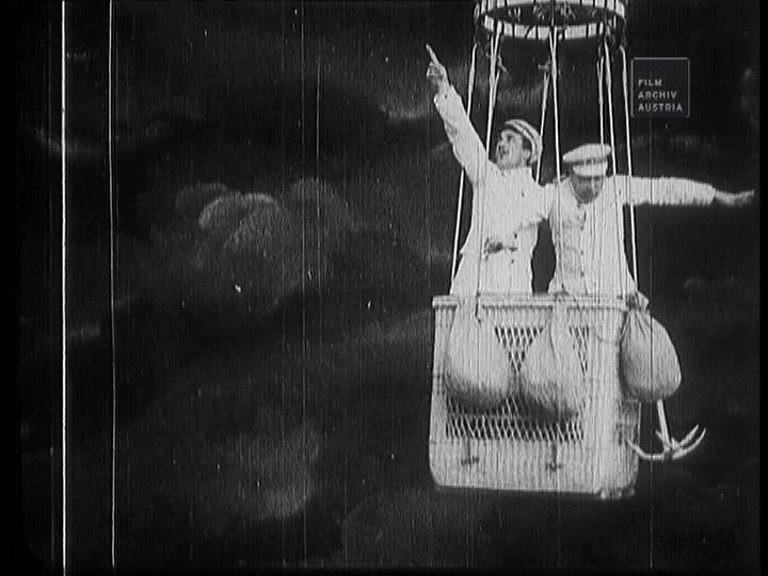

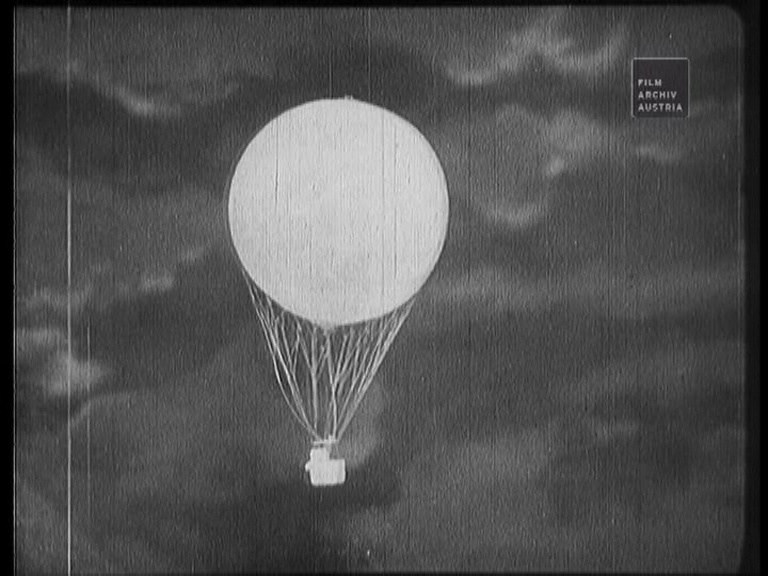

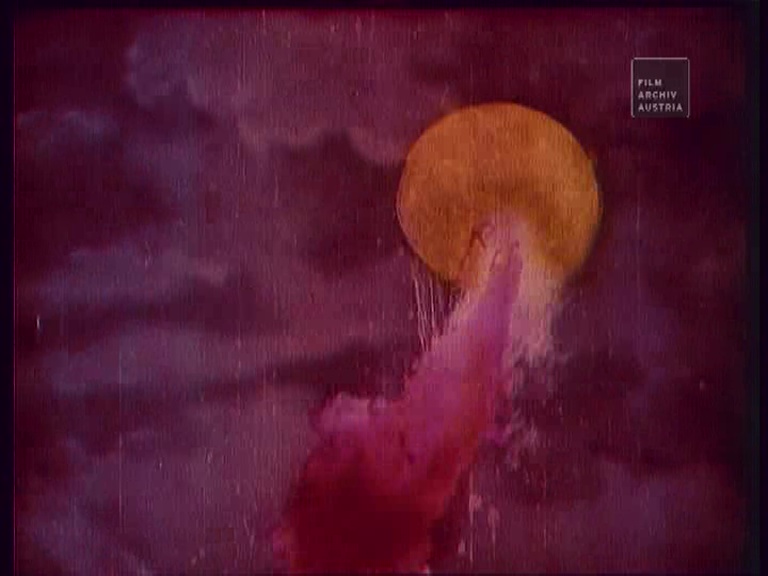

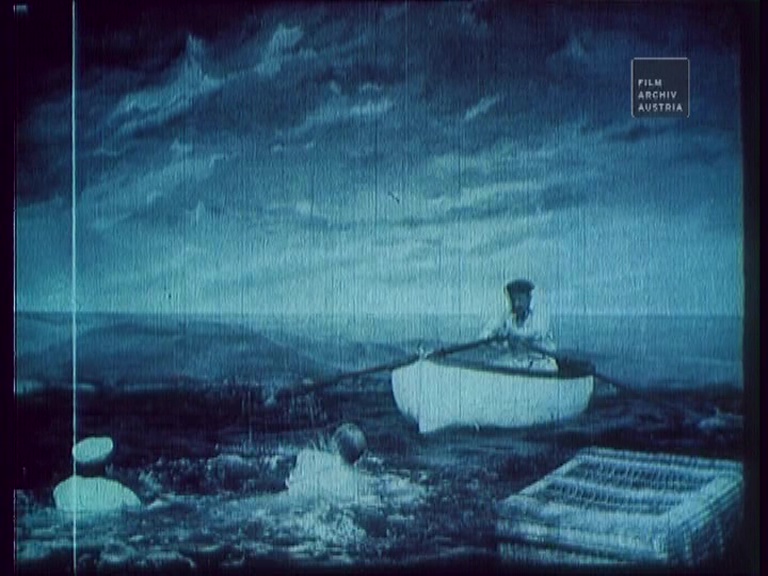

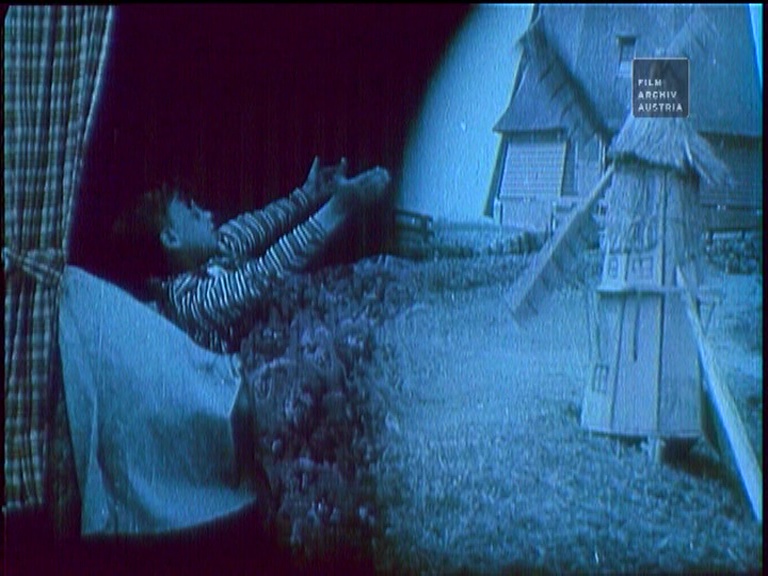

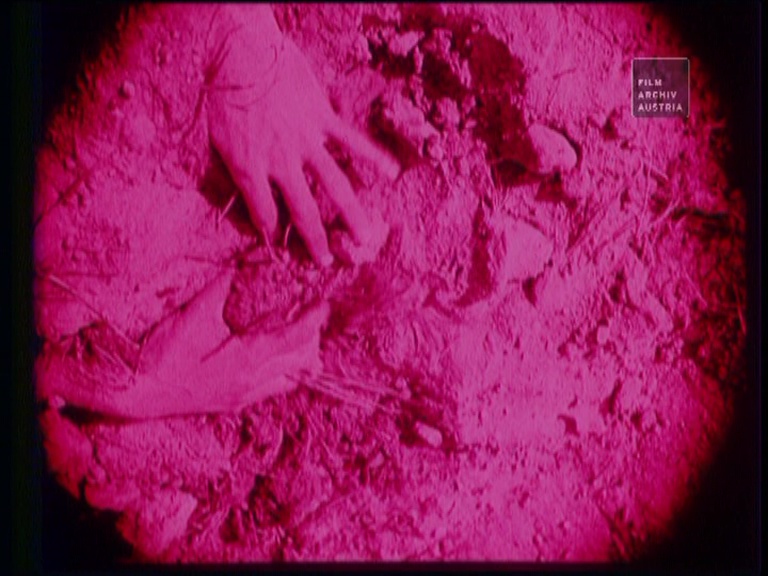

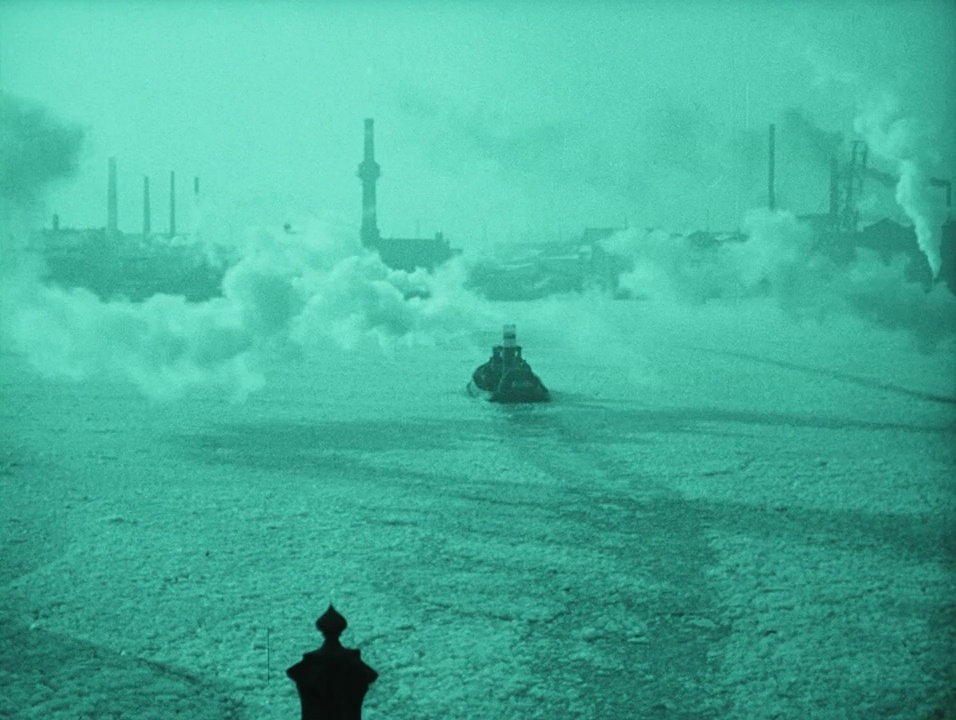

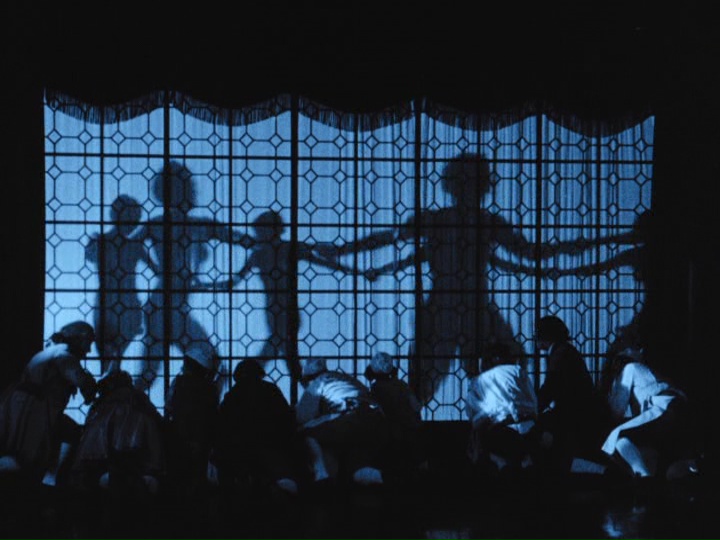

Then the film really hits its stride: a protracted chase sequence on a suspended railway that allows us fabulous tracking shots through town and along a river. (And yes, it’s the incidental details that attract the eye, which Piel surely included as part of the spectacle. His camera floats over the pre-war world of 1914. We take in the Metropolis-like suspended railway and its huge metallic supports astride the water, but we also see the horse and carts on the dirt road, and an old man—just a dark silhouette at the edge of the frame—scrapping debris from the roadside. It’s a world of mighty industry and primitive labour, of modern speed and ancient slowness. It’s absolutely beautiful to look at.) Abandoning high tech for low, Harrison comes across a group of what appear to be cowboys standing with their horses in a paddock. This raises the question of where the film is meant to be set. The English names suggest an Anglophone setting. Are we really to believe we are in America? It would at least explain the cowboys, incongruous in their damp field, breath clouding from their mouths. They are now embroiled in the chase, which proceeds (in ascending order of tech) via horse, then motorboat (the river scenes coloured a beautiful blue-tone-yellow), then car, then aeroplane. Shots are exchanged, tyres punctured, bombs dropped. Men in outlandish naval uniforms arrive, and Harrison parachutes out of the sky down (via a treetop) just in time to sabotage Baxter’s demonstration. Baxter then accidentally blows himself up on the lake, while Harrison and the police descend on the remaining members of the gang. The professor is liberated and successfully demonstrates his detonation. Father, daughter, and husband-to-be are united in happiness beneath the boughs of a blossoming tree. Marvellous stuff.

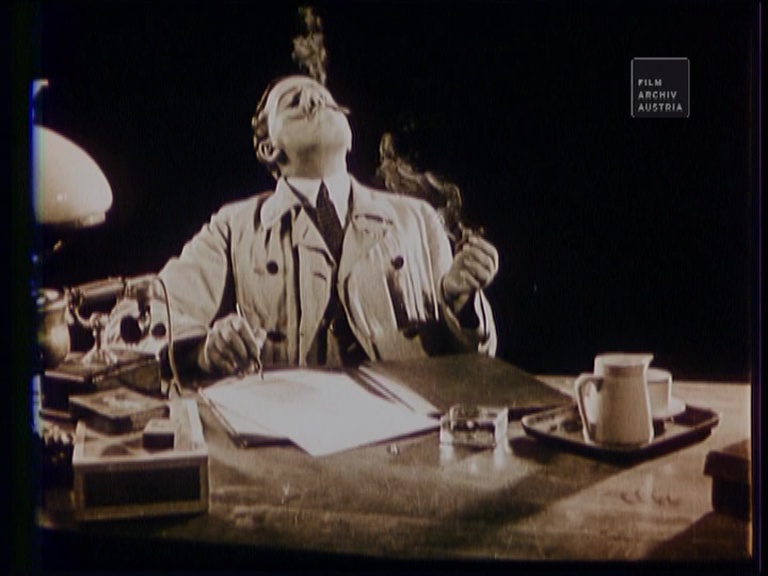

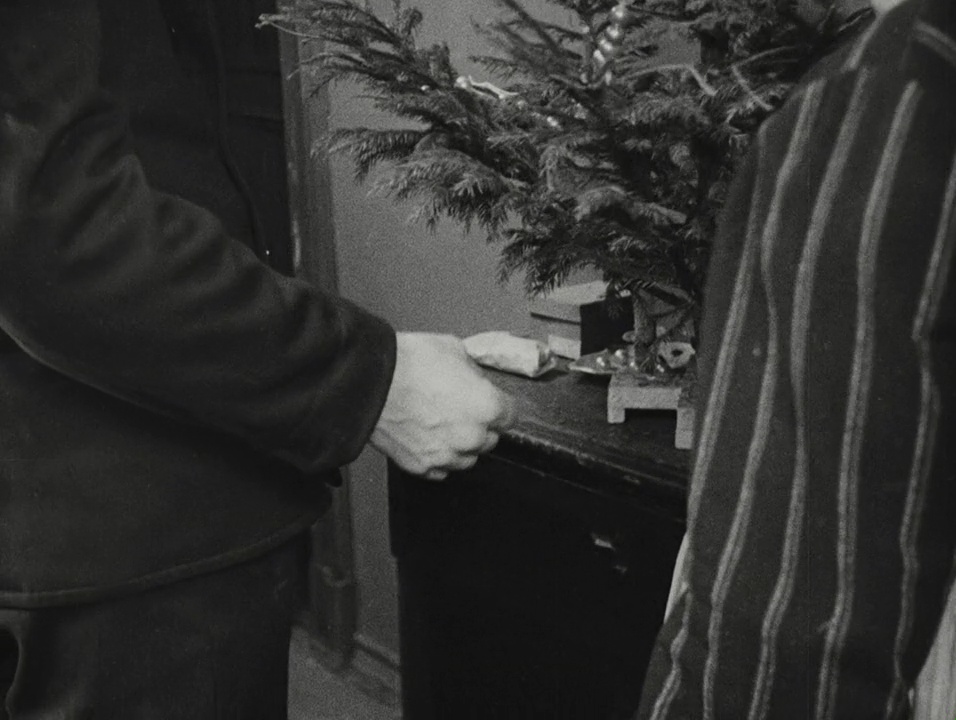

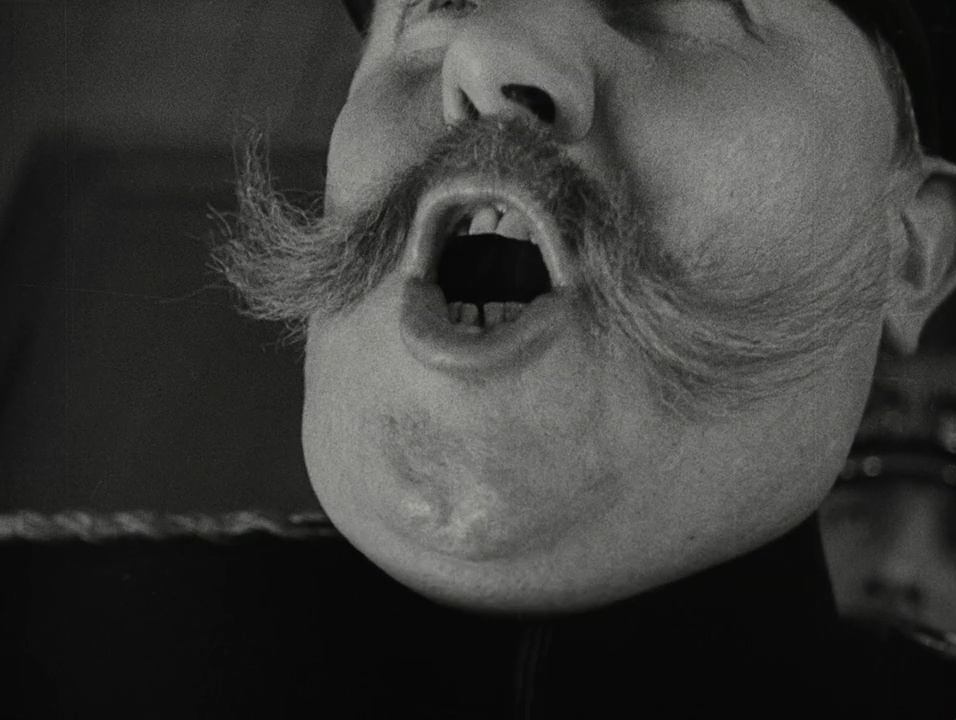

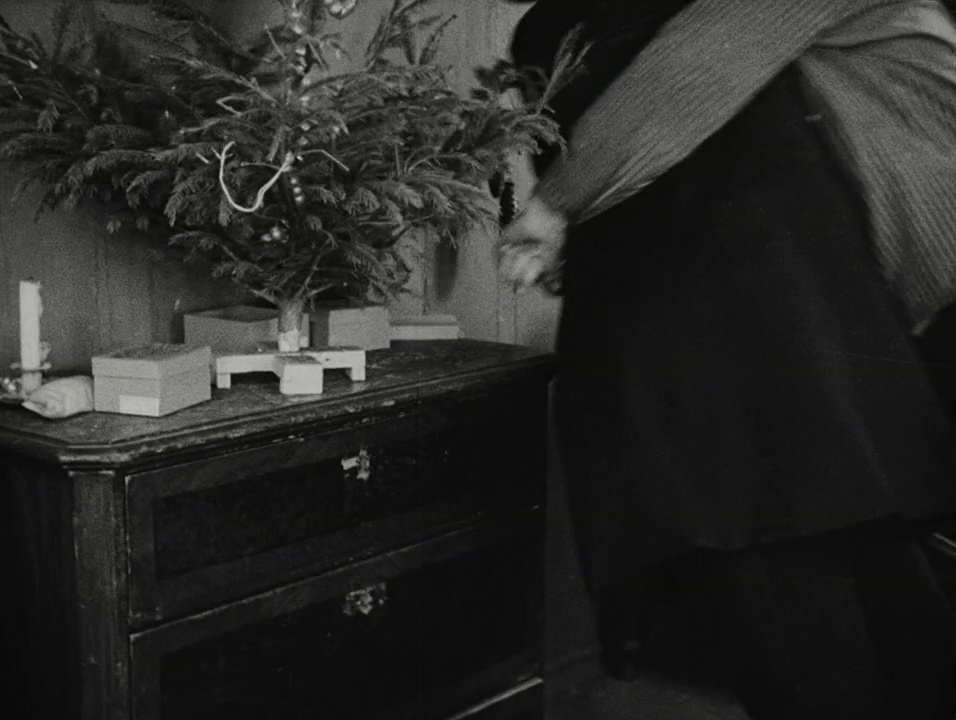

Das Rollende Hotel (1918; Ger.; Harry Piel). Meet Joe Deebs, the well-known private detective. (Have we met him before? Did other films exist? Do they still?) And meet Herr Parker, the fruit and veg wholesaler. (Fruit and veg wholesaler? Apparently so, and it’s the first sign that we’re not to treat what follows as seriously as anything in Das Abenteuer eines Journalisten.) Deebs is a debonair detective, with bowtie, boater, and cane. He has a half-smarmy, half-aloof air. Parker is a goatee-sporting pipe-smoker who wants his ward Abby to marry Johnson. But Deebs assures him that Addy will marry his friend Tom. Now meet Johnson: a short, bushy-browed, self-assured type: fingers covered in vulgar rings, showy belt, pale suit, cigar in mouth, and boater pushed languidly to the back of his head. Chez Tom, Deebs sips the tiniest possible glass of liqueur and sends another note of defiance back to Parker. And here is Addy, lounging on pillows, cradling a cat. In a rather confusing plot development, Parker tries to frame Tom in the vegetable stock market via his position as editor on “The Cauliflower”. Things are simplified when Deebs, disguised as a belligerent beggar, distracts Johnson and Parker so Abby can make a break for it. Deebs further arranges for two cars to distract the bicycle-riding Parker and Johnson to go around in circles, while Deebs boards the “rolling hotel” (the latest in caravan design) with Abby. They will stay there until Abby comes of age and can legally marry Tom. Parker and Johnson engage detective Scharf, who promises police support. Scharf traces them to Marienberg. To escape, Deeb sets the caravan rolling—only to end up plummeting off a high bridge into a river. Somehow they both survive and have supper in an inn, then set off up into the mountains. At a refuge on the Zugspitze, Deebs and Abby look down across the snowy Alps. But Scharf is still on their trail, so they take the “unfinished” cable line: Deebs carries Abby on his back as he walks across a tightrope from one side of an abyss to the other. (Some genuine stunts, but also sleight-of-hand camerawork.) Next, to Seefeld. Deebs and Abby enjoy some fine dining, while Scharf huffs and puffs and sits in a train station waiting-room moodily sipping beer. When he arrives at the hotel, he finds another mocking note from Deebs. So while Parker and Johnson take the train, Scharf takes a racing car to try and catch up with the other. (Cue real trains and cars, together with an aerial model shot to set the scene.) Scharf catches up, but only after time enough has passed to allow Abby and Tom to marry on the train.

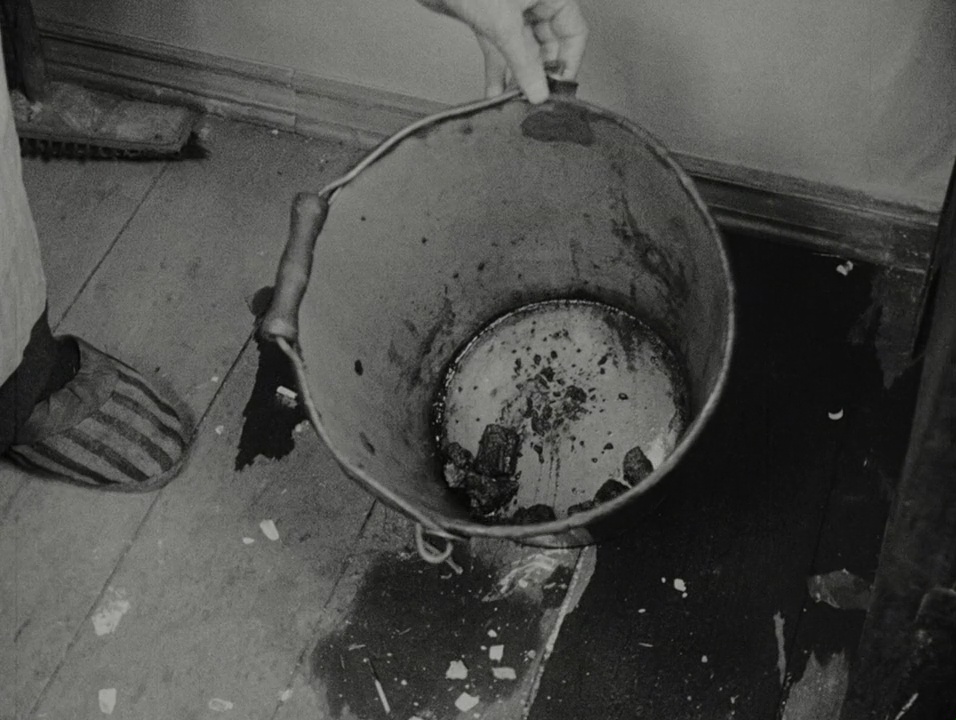

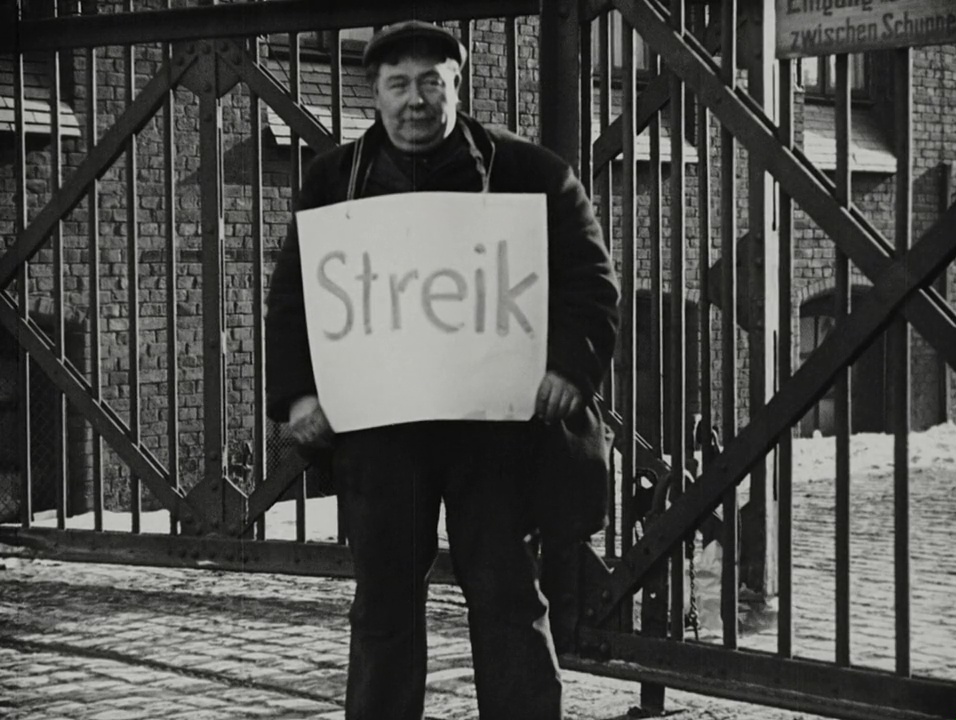

An odd film, and not what I was expecting after the first by Harry Piel. Rather than a crime caper, it’s more of a comic travelogue. The film came out in September 1918, so it’s perhaps not surprising that Piel wanted to give his audience a world free of serious crime and death. The comic tone of the film and easy way of life in the rolling hotel must have been a great contrast to the economic collapse, political turmoil, and food scarcity afflicting Germany at the end of the war. I’ll happily take the nice location shooting, but it’s a tame, meandering film compared to the propulsive adventure of the first.

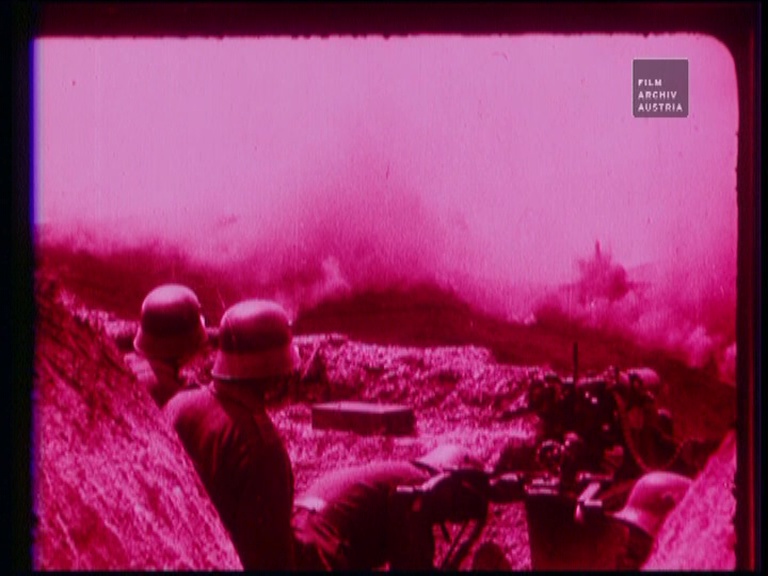

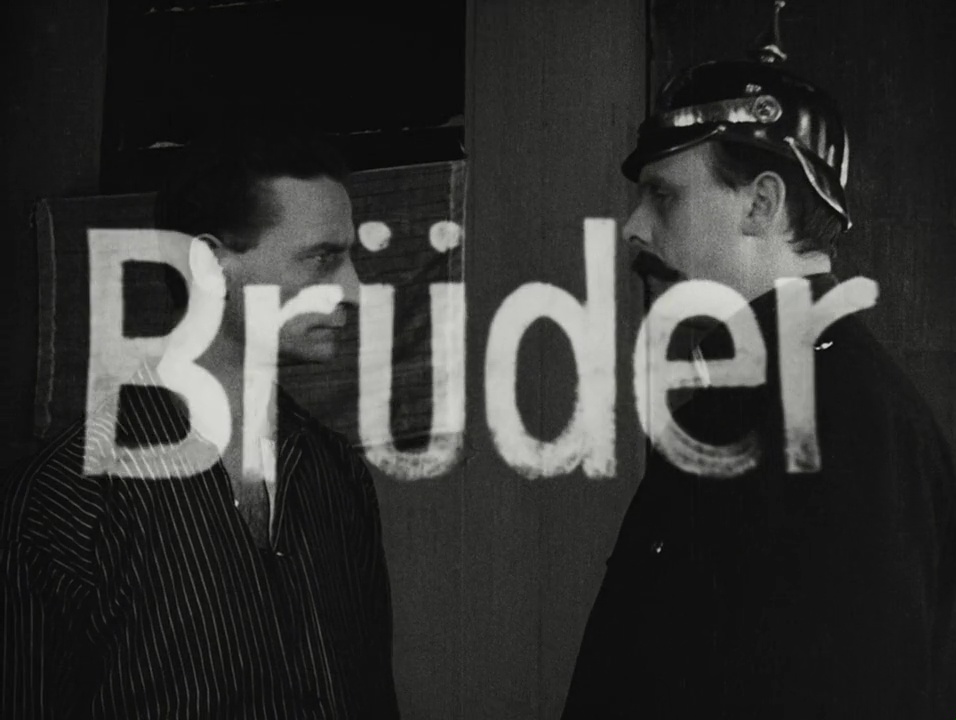

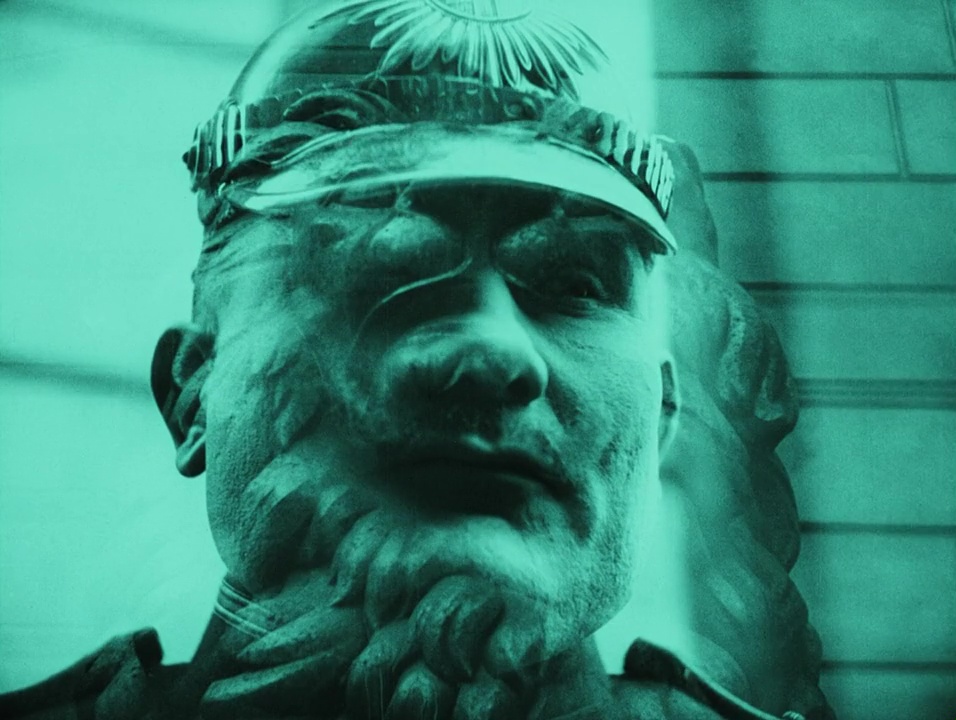

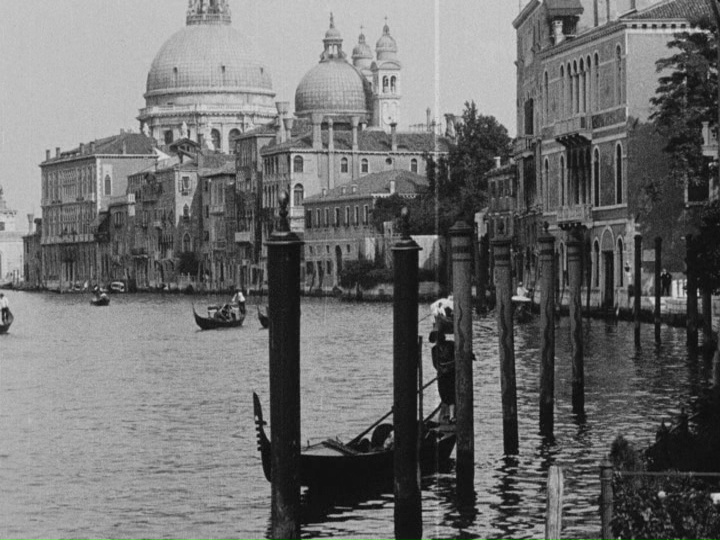

Der Berg des Schicksals (1924; Ger.; Arnold Fanck)

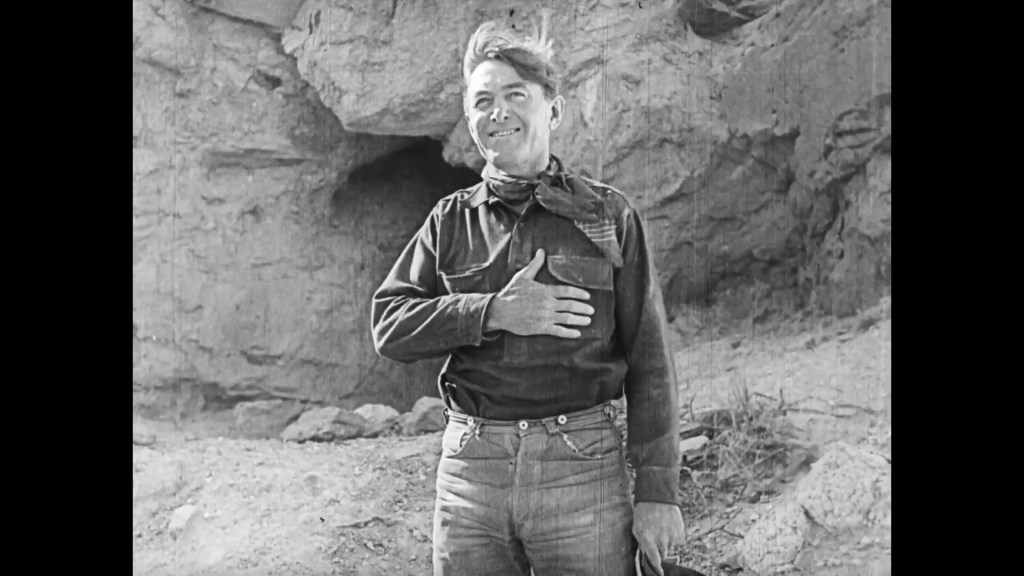

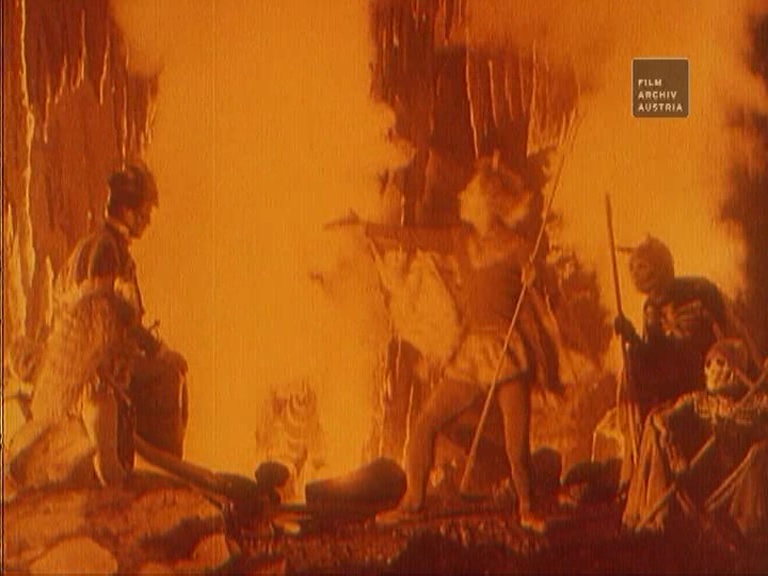

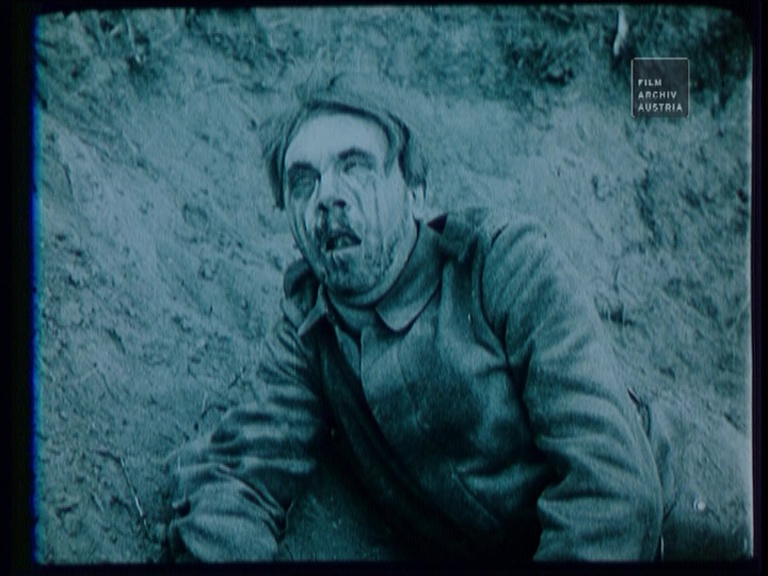

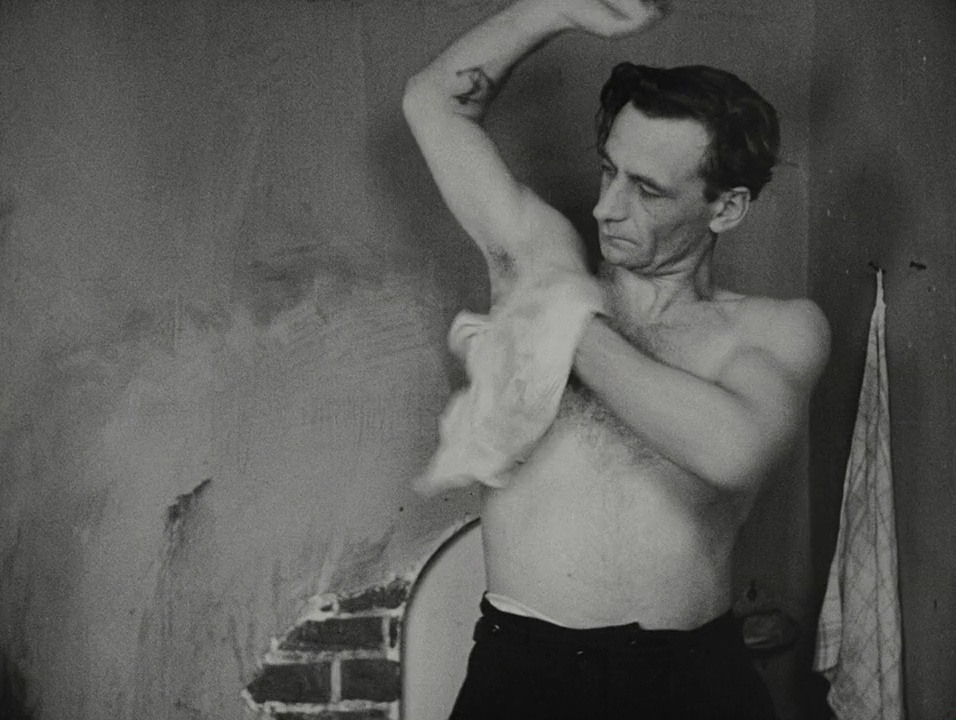

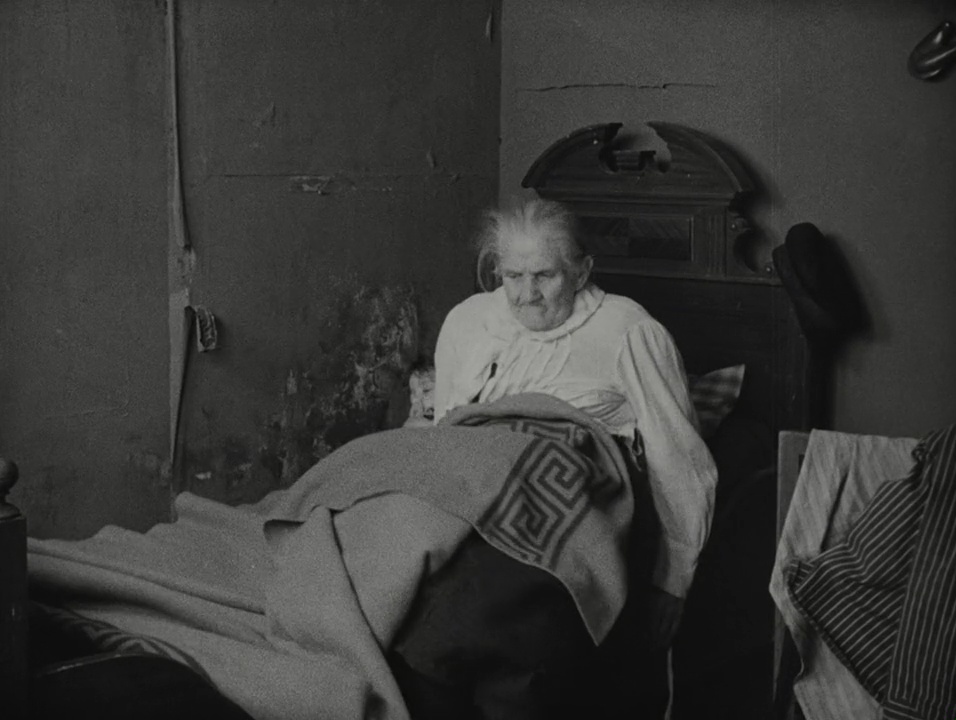

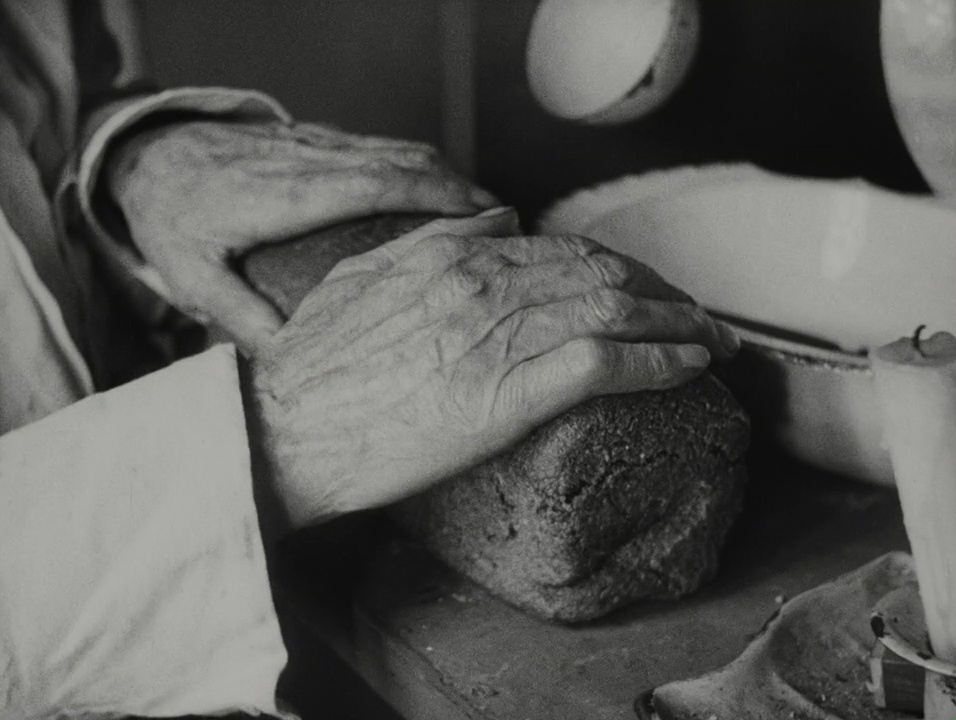

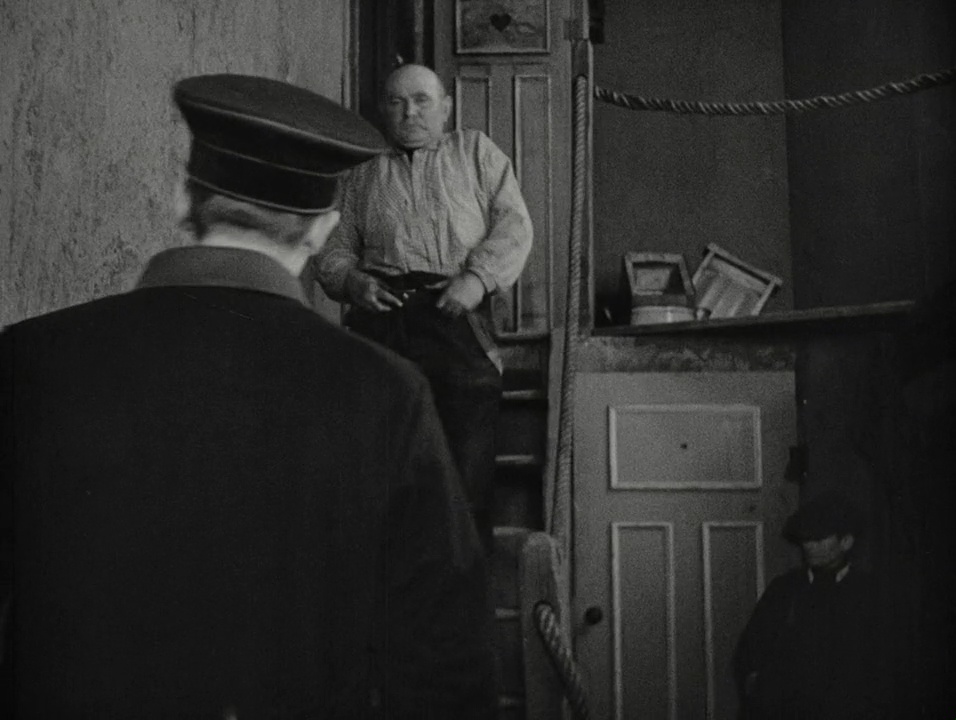

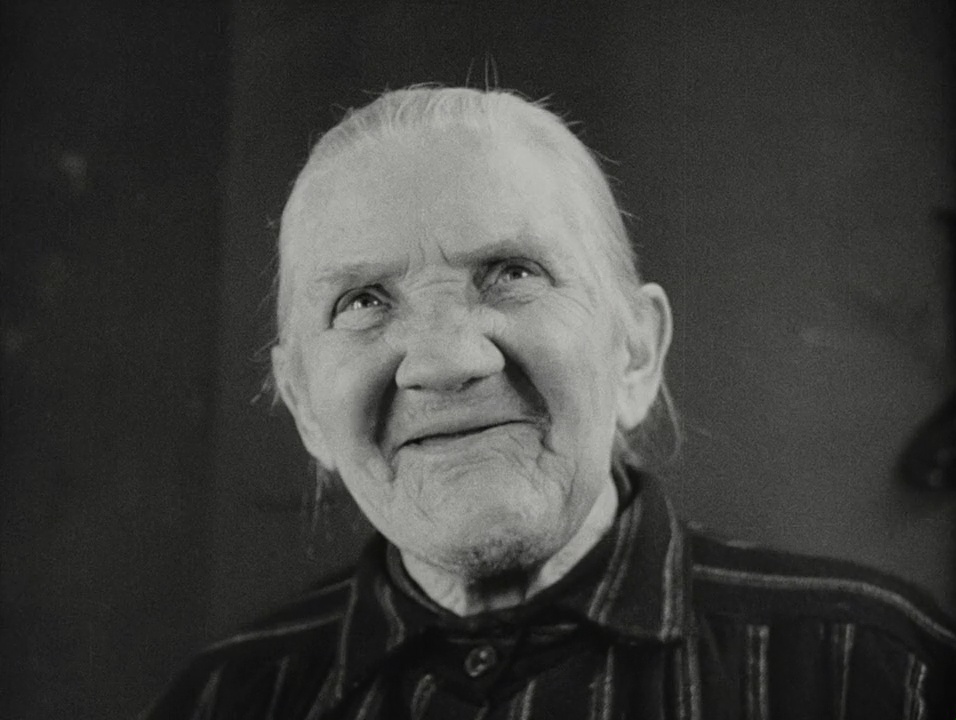

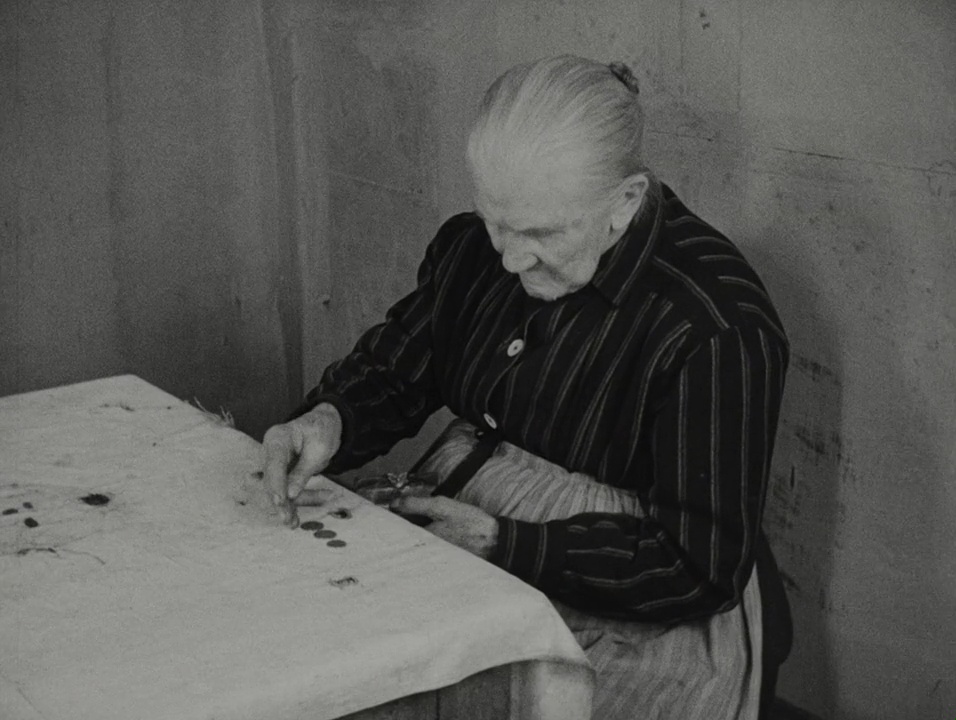

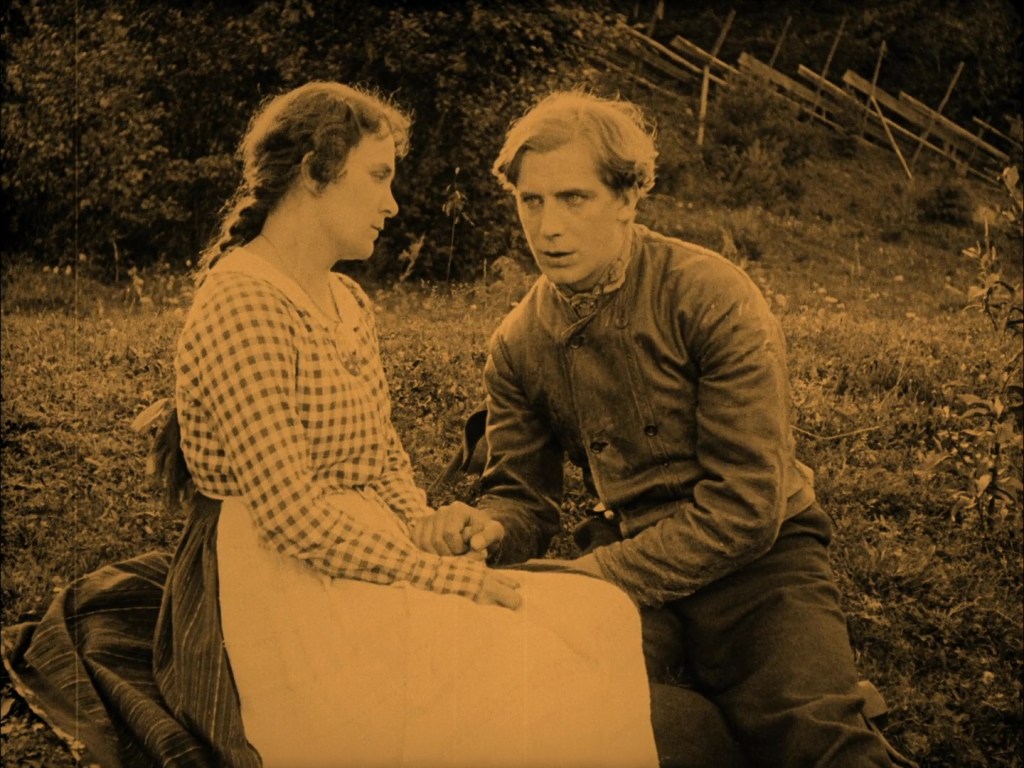

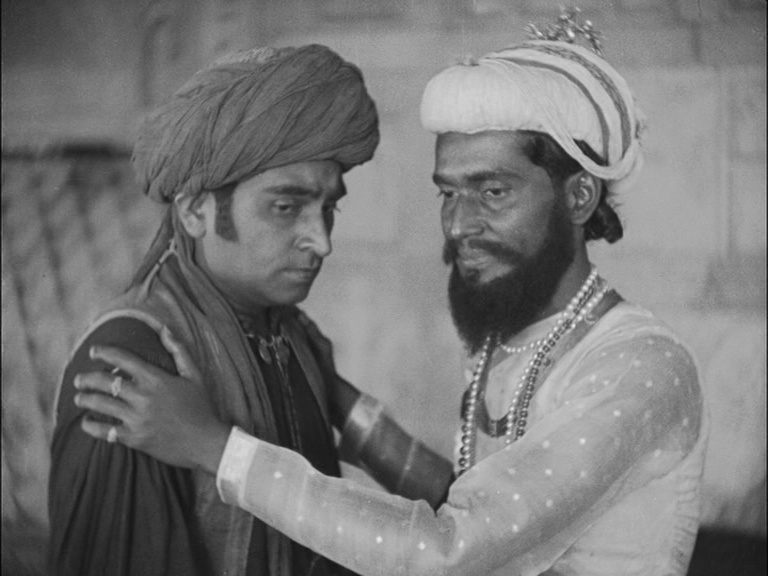

The Mountaineer (Olympic skiing champion Hannes Schneider) is obsessed with conquering the “Guglia del Diavolo” peak in the Dolomites. Though his Mother (Frieda Richard) is supportive, his Wife (Erna Morena) worries for his safety and the future of their young son. During one final attempt, the Mountaineer falls to his death. Many years later, his adult Son (Luis Trenker) has himself grown to be an expert climber. But in deference to his father’s fate, he refuses to climb the Guglia, even though two rivals are setting out to be the first to reach the peak—and even though his love interest Hella (Hertha von Walther) calls him a coward. But he has promised his mother he will never climb the Guglia, so he goes back home—and Hella determines to conquer it herself, beating the two rivals to the top. But a storm strikes the mountain: the rivals reach the summit, but are killed in the descent, while Hella is trapped on a ledge. The Son hears her distress signal and (with Mother’s permission) sets out to fulfil his destiny…

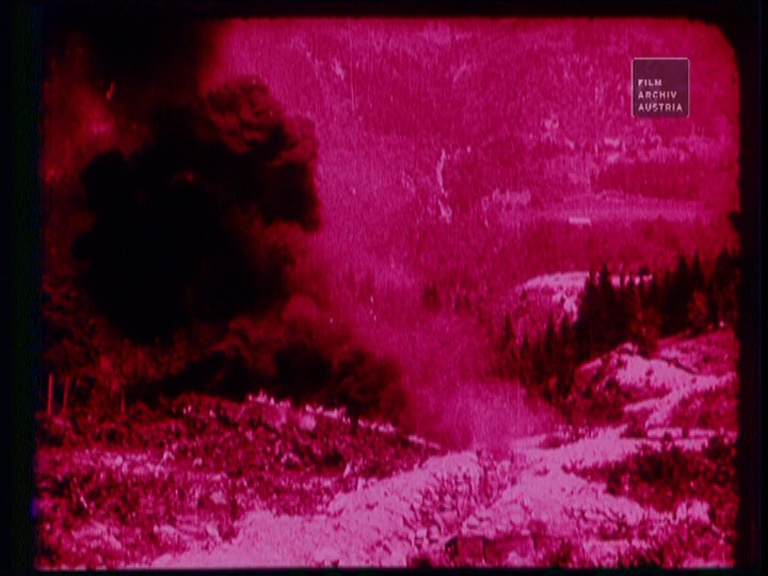

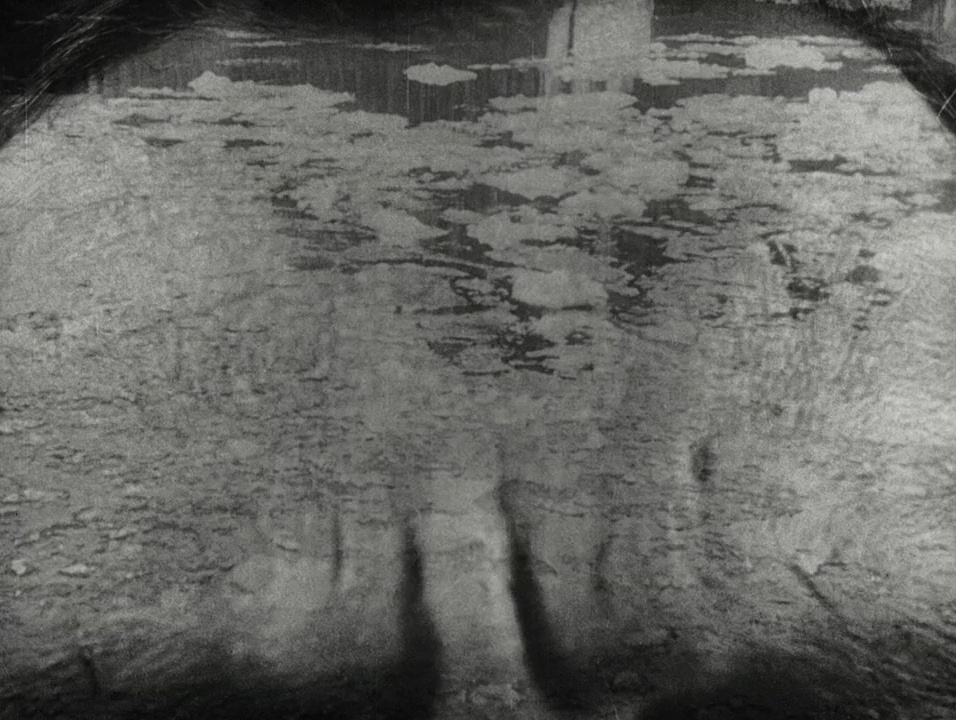

First thing’s first: Der Berg des Schicksals is a masterpiece. The location shooting in, around, and atop the Dolomites is some of the most beautiful I’ve ever seen. I wrote some months ago about Fanck’s Im Kampf mit dem Berge (1921), which is an astonishing work: but I think Der Berg des Schicksals betters it. The film’s credits name Fanck himself as the chief cameraman for the exteriors, with special credit for photography taken on the mountainside itself by the climbers [Hans] Schneeberger and [Herbert] Oettel. The sheer physical effort of making this film is extraordinary. You know that everything done on screen was done by the filmmakers themselves to take the shots we watch. You see men and women clinging on to sheer cliff faces hundreds of metres above the valley, with absolutely no safety net—and you know that the cameraman has done the same, lugging cumbersome equipment with him.

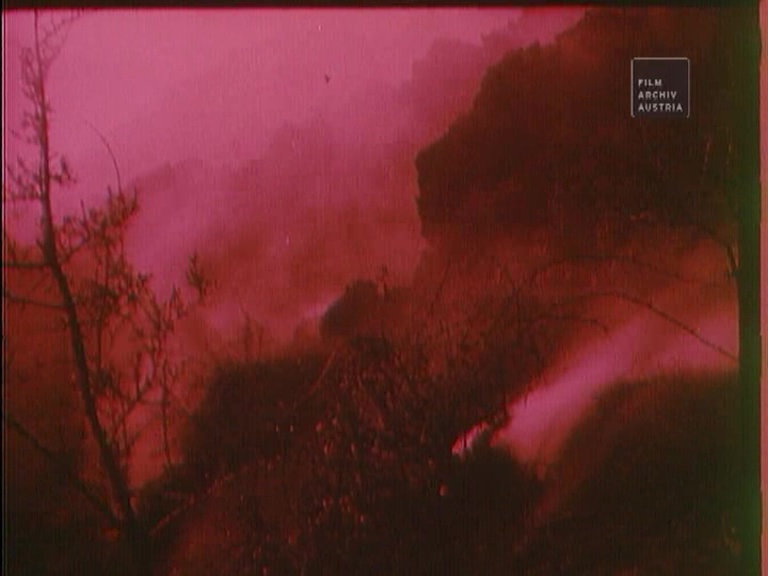

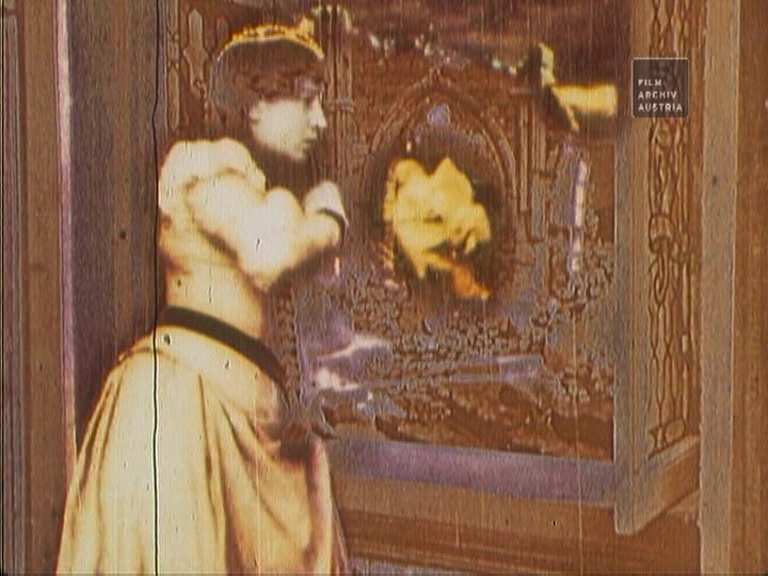

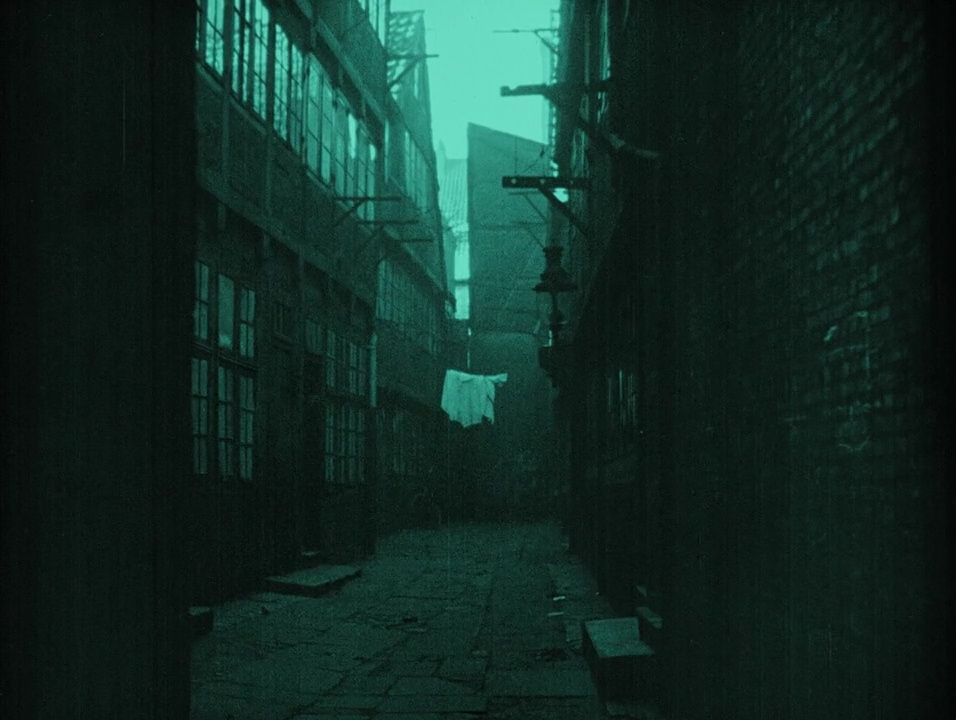

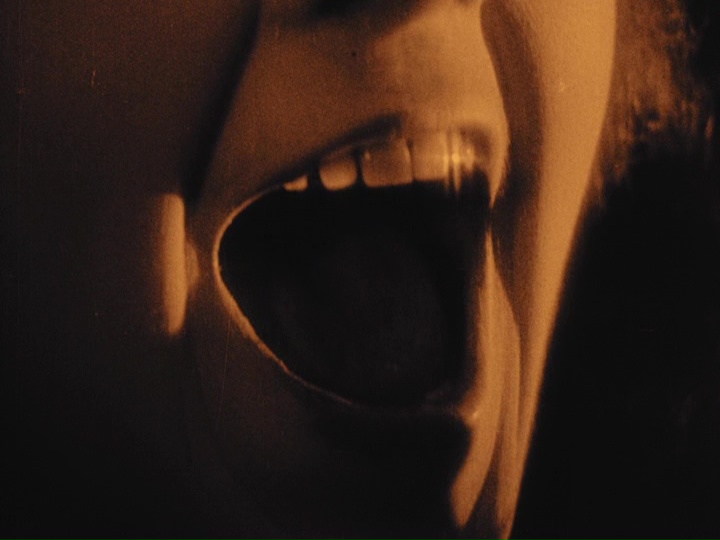

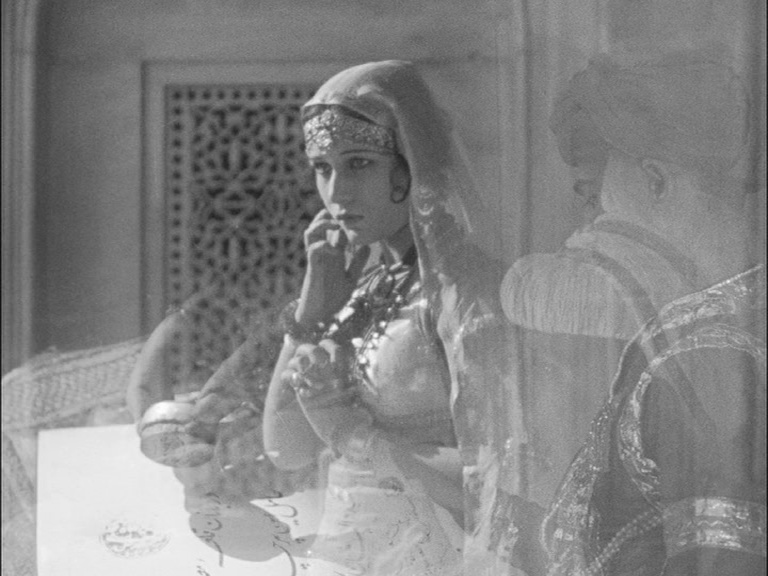

The results of this effort are magnificent. I could take literally hundreds of image captures from this film and it wouldn’t be enough. Peaks and snows and clouds and skies are almost overwhelmingly beautiful to look at. The vistas awake in me a desperate longing for travel, while the glimpses into deep abysses below the climbers make you dizzy—with exhilaration, with fear, with envy. Compositions heighten the suspense, bring out the savage and surreal qualities of the landscape. Teeth-like promontories. Fist-like boulders. Axe-like lumps of rock. Mountains looming menacingly behind dark pools. Mountains like curtains of mist floating in the distance. Hazy valleys crisscrossed with white tracks, without humans or even trees for scale. The spaces here are extraordinary, but so too is the sense of time. Progress can be fingertip by fingertip up a limitless cliff, or giant strides silhouetted above tiny mountains. Seasons move strangely. From the pinks and golds of blazing daylight to the blues of storm-induced winter. And with time-lapse photography, you can watch weather fronts brood and bloom over the black mountaintops, or see the night’s snow melt at dawn into sheets of gleaming water. I could spend hours dreaming amongst these images.

My favourite moment is when the Son finally reaches Hella on her remote ledge. He has achieved the summit, where his father never trod. But the Son was not the first to get there: the unknown climbers (now dead) reached it before him. Though the mountain is prominently phallic (Fanck even masks the edges of the frame to emphasize its verticality), the film isn’t as obvious as about its masculinity as you might think. The Son reaches the summit and pauses, almost sadly, to reflect on his father’s death. He doesn’t conquer the mountain, there is no sense of triumph, for it has already been conquered by strangers. And his real mission is to find the woman he loves, who has also ascended the mountain before he has. When they meet, Fanck cuts away from their embrace to a series of shots of the moving clouds around the peaks. The film refuses a kind of resolution (or consummation) of the central relationship on screen: instead, all our emotions are transposed to the landscape and skies. It is an ecstatic sequence, and I found it incredibly moving—though I’d be hard pressed to explain quite why. Just the sense of longing and space and grandness of the landscapes was suddenly the whole focus of the film. As Werner Herzog would say, this is a landscape of the soul on screen.

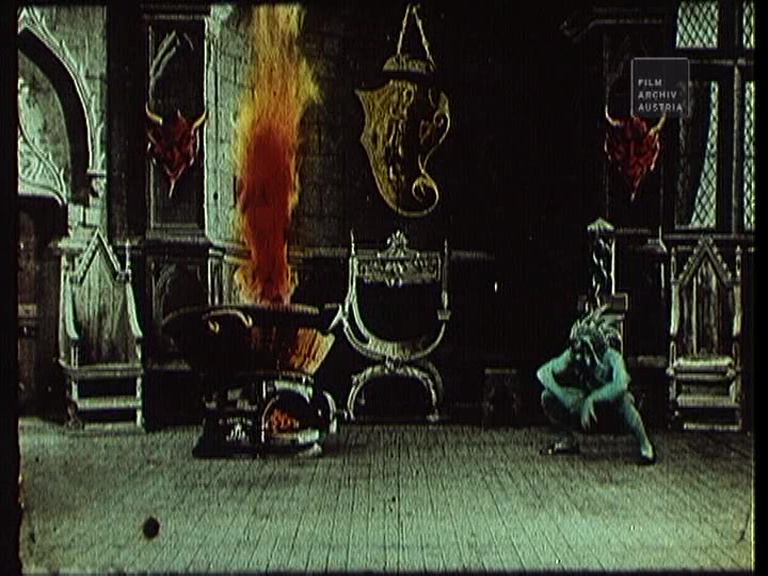

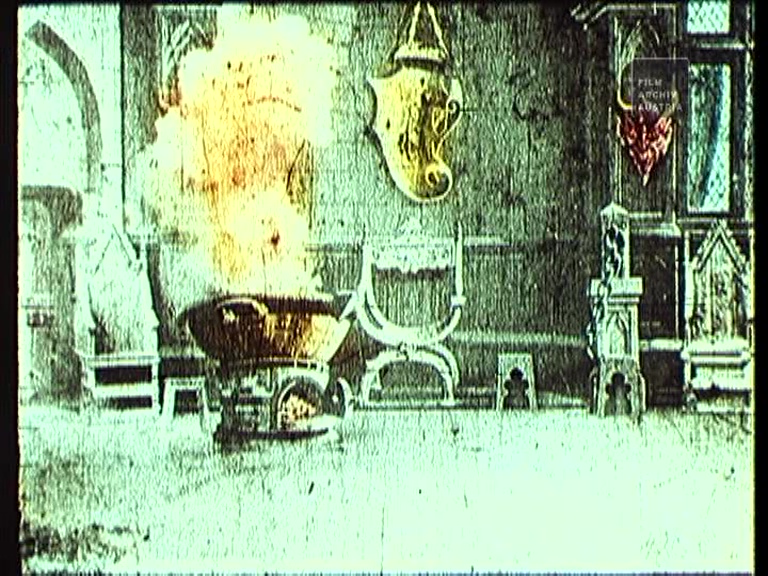

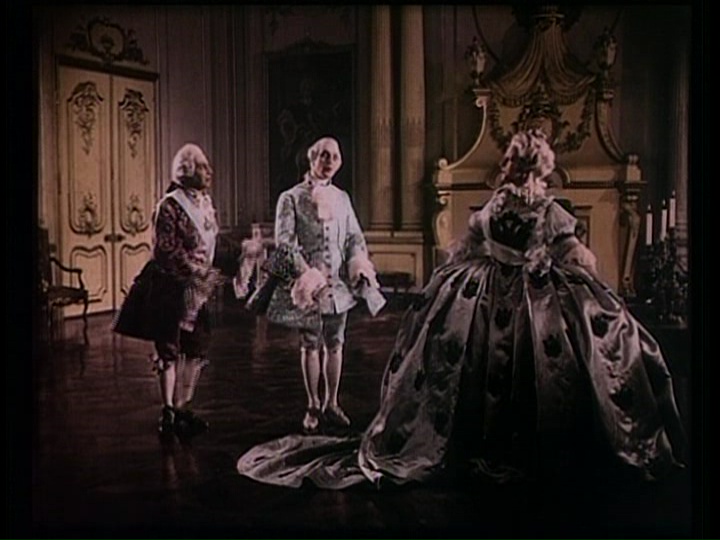

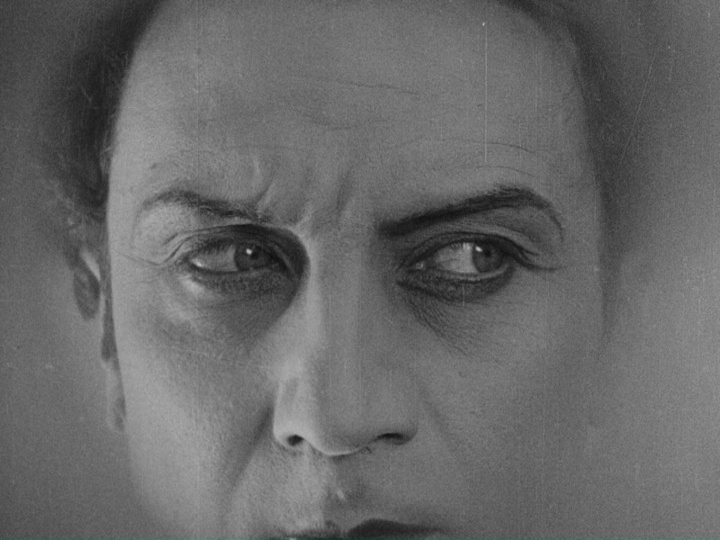

The film’s tinting heightens all this atmosphere. It transforms the exterior spaces into supranatural vistas, gleaming and glowing with colour. Though you long to visit the places you see, they could never look quite like this: they are at once natural and supernatural. Most impressive of all is the use of rapid cutting between blue (for night) and overexposed monochrome (for lightning) in the climactic scenes. These effects are all done mid-shot, so as the Son climbs the mountain he traverses bursts of colour and blinding light. It’s the single most effective rendering of lighting that I can recall in any silent film, and frankly in any sound film that I can recall. There are individual frames that are simply astonishing. When there is a close-up of Trenker, “On the summit that was his father’s longing”, lightning flashes and Trenker’s face becomes (in a single frame of celluloid) a charcoal sketch on bleached parchment. It’s breathtaking imagery.

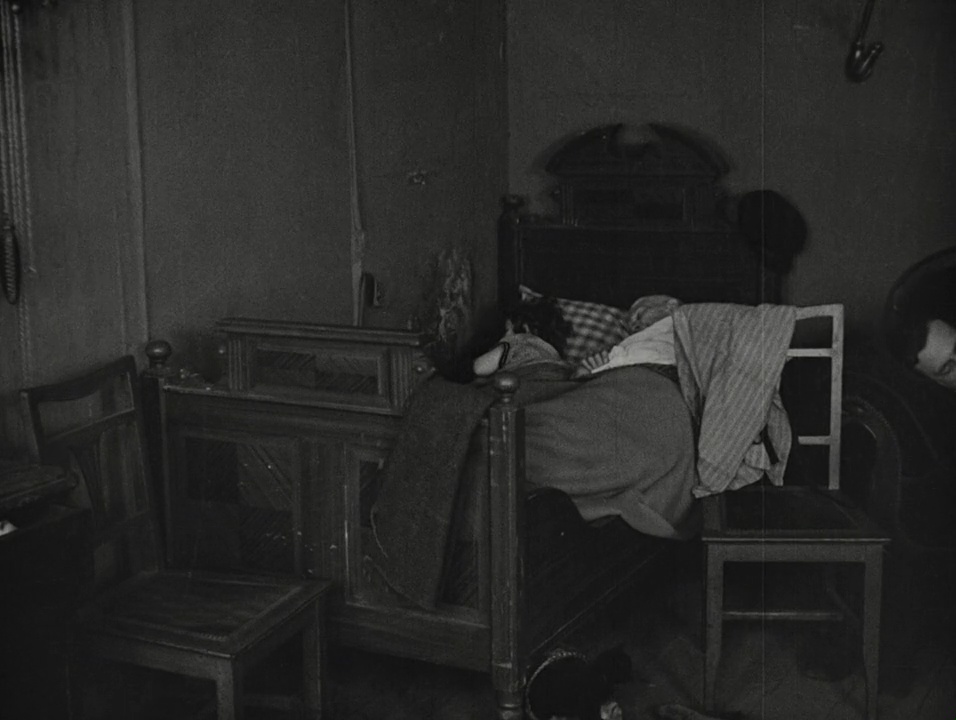

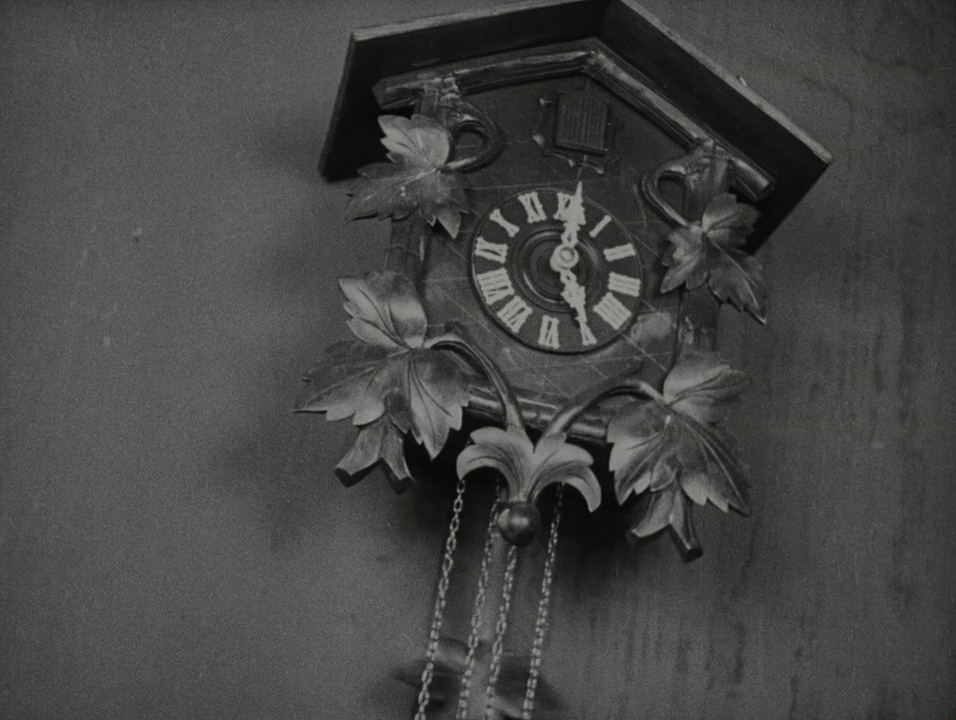

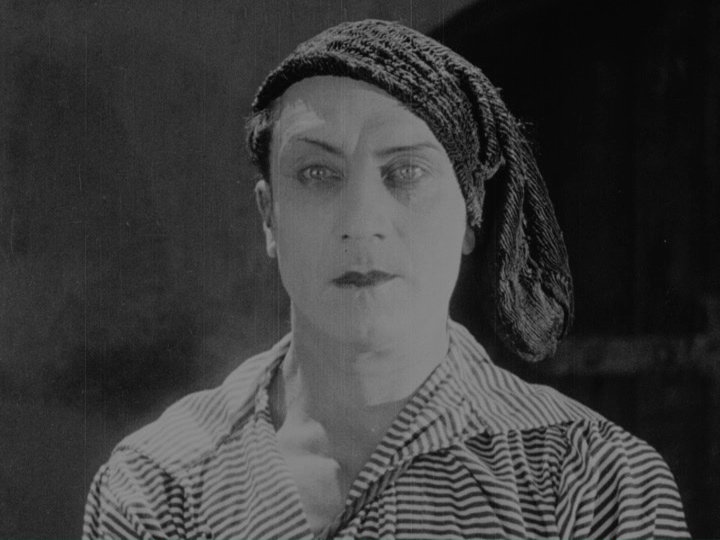

The interior spaces are nicely designed and lit, too, but the division between interior and exterior spaces grows more absolute as the film continues. This serves to further separate the world of the older women—the Mother and Grandmother—and to make the finale all the more strange and compelling. For the film cuts between the Mother looking up expectantly and the progress of the Son and Hella making their way down the mountain. The close-ups of the Mother’s face are clearly a kind of reaction shot—but a reaction to what? Since the film doesn’t show her near a window, there is no evidence that she can the mountainside. (Even if she could, she could not have the proximity to the events the camera has. Earlier scenes have shown that you need binoculars to get even a glimpse of any figures on the mountain there.) And when she assures her stepmother that the Son is safe, her phrasing—“I know it, he is down”—confirms that she has had no direct sight of them. (She doesn’t say “I can see him, he is down”.) It turns the triumphal descent into a kind of vision, making the final image of the lovers seem further beyond the bounds of realism. And what a final image this is: the circular masking makes the lover an entire world, a world filled with light and cloud and possibility. It is another ecstatic image. Ende.

Day 2: Summary

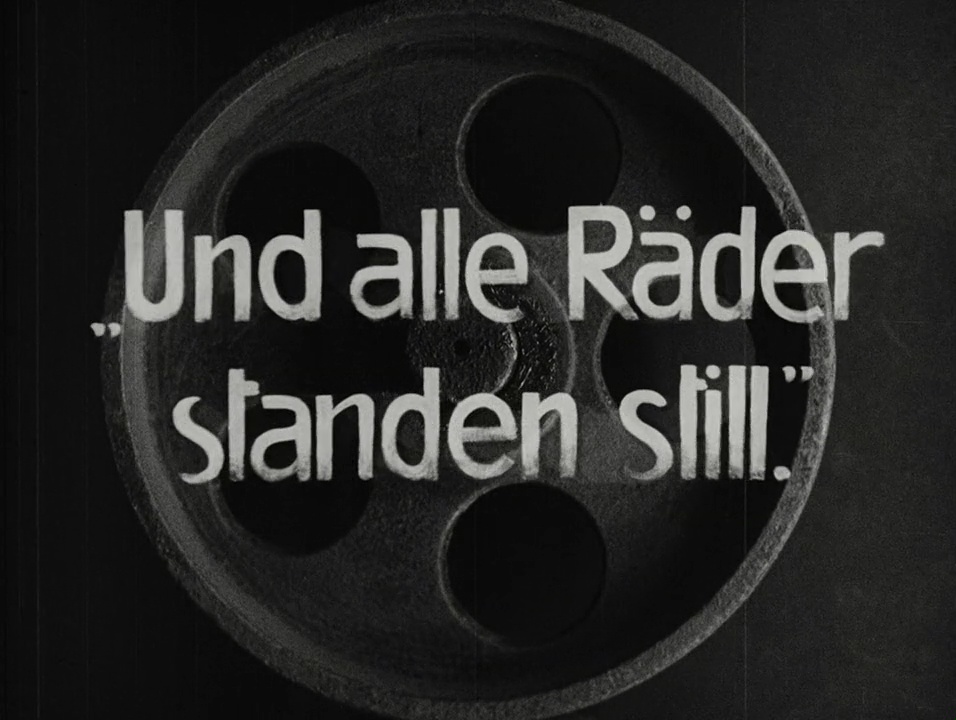

A supremely entertaining and beautiful day of films, with a generous combined runtime of well over three hours. It was my first time seeing the work of Harry Piel, and I’d be very curious to see more—especially any films in which he appears as actor. The introductory titles for the films say that both are incomplete, a result of most of Piel’s work being partially or totally destroyed during the bombing raids of WWII. If there are more along the lines of Das Abenteuer eines Journalisten, then I’d take even a series of fragments. Give me more suspended railways and crazy chases via plane, train, and automobile through Wilhelmine and Weimar Germany!

This was my second time seeing Der Berg des Schicksals. The first was last summer, when the film was shown (and streamed) as part of “Ufa Film Night” with an orchestral score by Florian C. Reithner performed by the Metropolis Orchestra Berlin. After getting over the initial shock of a yodel-esque vocal line (which seldom recurs), I found that score wonderful. Der Berg des Schicksals is a film that absolutely requires an orchestral score. The piano accompaniment by Mauro Colombis was very good for this presentation from Pordenone, but I longed for the richer, wider, grand soundscape of an orchestra—something that could truly match the scale of the images. Just see the recent restoration of Fanck’s Im Kampf mit dem Berge with Paul Hindemith’s original score from 1921 to know what great music can do to such a film. And I long to hear the original Edmund Meisel score reunited with Der Heilige Berg (1926) (for some strange, possibly legal, reason, Meisel’s score—which is extant and has been recorded separately—has never been shown with the film in the modern era). And for the rerelease of Fanck’s Die weiße Hölle vom Piz Palü (1929) with the excellent orchestral score by Ashley Irwin (or Schmidt-Gentner’s 1929 score, should it be rediscovered). I would easily put Der Berg des Schicksals in this company—if not ahead of it. (The film is less pretentious than Der Heilige Berg and far more concise than Piz Palü—and no Leni Riefenstahl either!) I do hope that Fanck’s film is released on Blu-ray, and that a full orchestral score accompanies it. The film is superb and deserves the best possible treatment for audiences everywhere.

Paul Cuff