In 1926, Marcel L’Herbier’s production company Cinégraphic was in dire financial straits. It had financed several films that made no money and consumed progressively larger budgets: Autant-Lara’s avant-garde short Fait Divers (1923), Louis Delluc’s feature L’Inondation (1924), Jaque-Catelain’s two directorial efforts Le Marchand de plaisirs (1923) and Le Galerie des monstres (1924), and finally L’Herbier’s own studio spectacular L’Inhumaine (1924) and Pirandello adaptation Feu Mathias Pascal (1926). L’Herbier needed his next film to be easier to make, cheaper to produce, and more commercially appealing. This was to be Le Vertige, an adaptation of a play by Charles Méré (1922)—a work that foreshadows the same themes of obsession with a “double” in Hitchcock’s Vertigo (1958). L’Herbier’s regular collaborator (and lover) Jaque-Catelain was to play the lead, alongside Emmy Lynn and Roger Karl (both of whom he had also worked with before). He enlisted another regular collaborator, the architect Robert Mallet-Stevens, to design the sets. Exteriors were shot rapidly around Eden-Roc and Eze on the Côte d’Azur, then the production returned to Paris for a lengthier period shooting interiors in the elaborate sets. The film was indeed a commercial hit, something of a surprise for L’Herbier. But despite (or perhaps because of) this, Le Vertige is a rather overlooked film in the director’s work. Is this deserved?

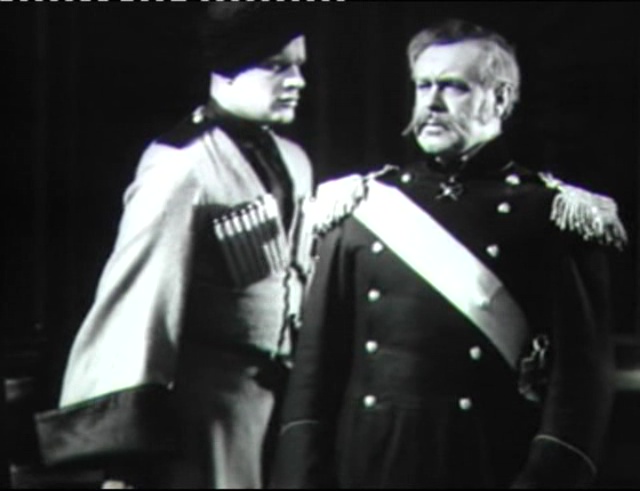

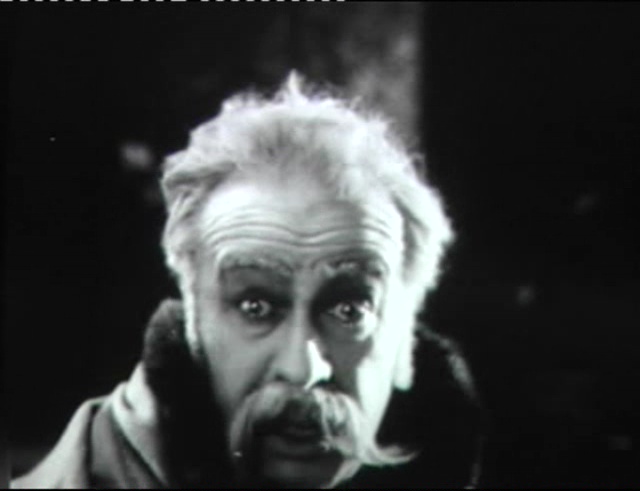

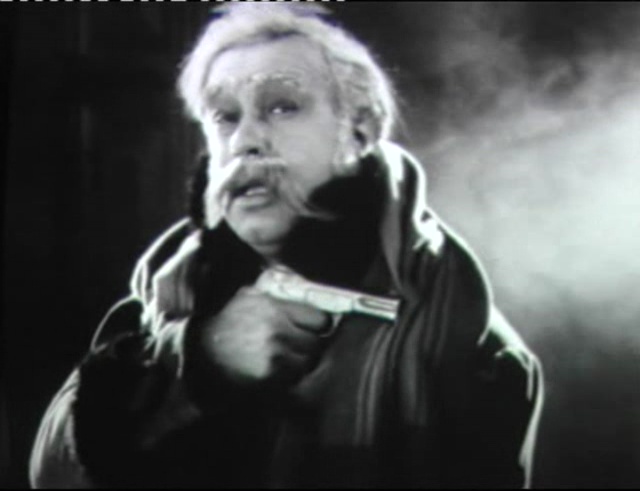

The “vertigo” of the opening title is induced by delicious lines that form a false perspective, funnelling down into the L and V of the film’s title. It is 1917, Petrograd. A snowy square. Events overseen from the windows of a house. Count Mikailov (Roger Karl) and his young wife Natacha (Emmy Lynn). But whose return does she anxiously await, a title asks us? It isn’t her husband, given a foreboding entrance—composition in depth, doors opening, guards on hand. Roger Karl is, as ever, a stern elder figure—made sterner, but also more comic, by a huge moustache and picture-book epaulettes.

A commotion outside. Shots fired, crowds running. Shadows on projected on glass. A boy runs in to warn of the dangers. The women, dressed for the summer-conditions of the palace interior, run behind the huge columns of the hall. Fur coats are donned, they scamper out. (The window recesses narrow at the top, like the shape of a coffin.)

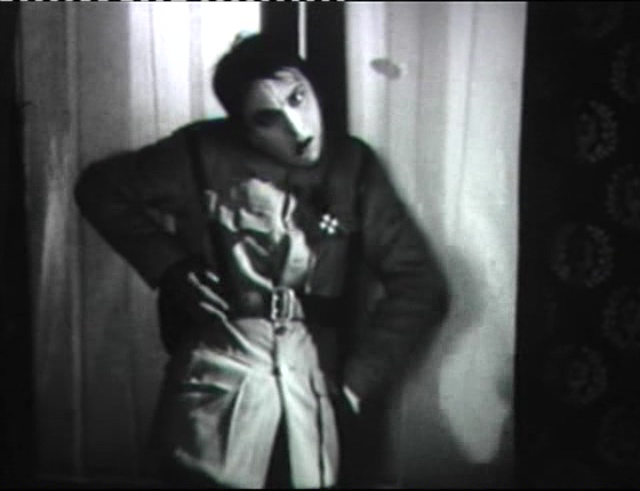

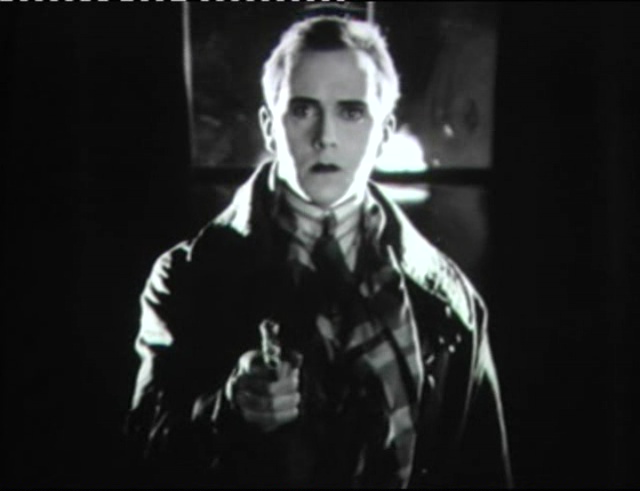

Dimitriev is on a dangerous mission. He is played by Jaque-Catelain, and he makes quite the entrance: in silhouette, horse hurtling and rearing into the camera. Dimitriev causes a stir in a local hovel, filled with roughs. (Meanwhile, Natacha is on her knees praying—and looking ever so elegant as she does so, her drooping black sleeves embellishing her form as she holds out her arms.)

The General finds a photo of Natacha and Dimitriev together (no, not like that—staged, but intimate). And Dimitriev arrives, beckoned in eagerly by Natacha. They run at each other, and L’Herbier’s camera twists to catch Natacha’s last leap into his arms. The couple escape their present danger by remembering the past… A flashback to the scene captured in the photo, here spelt out in a single tableau of dancers, of shadows, of an embrace. (But I’m not moved, nor is Petrov, the guard, who spies on the lovers in the present—he almost looks to camera, as if to say, “What nonsense”.)

Past and present are intercut. A ring is given (then) and contemplated (now). The palace doors open. It is the wind, or is it? The sinister Petrov waits for Dimitriev, ushers him out—and into the presence of the General. He takes the young man to task for disobeying his orders, for deserting his mission on the revolt’s frontline. (Catelain looks like a schoolboy in a play, caught out for forgetting his lines.) He is threatened with martial law. The General shoots him. He clutches his face, which is apparently unharmed, then lurches to a window—L’Herbier cuts to soldiers scurrying past (perhaps remembering Gance doing the same, to much better effect, in J’accuse in 1919). Natacha sees his last moments, and faints. They both lie in pools of light. She is revived by the General, just as his palace is being stormed by the mob. Husband and wife flee, and the soldiers plunge their bayonets into the corpse of Dimitriev (though L’Herbier cuts just before the final thrust).

It’s a half-hour prologue to the main timeline of the film. On the Côte d’Azur, the General (now in evening wear) and Natacha (diaphanous swirls wreathed about her shoulders) recover from their ordeal. Outside, a motorboat plunges through sparkling waters. Crowds of pleasure-seekers observe the boat race. Natacha still has her “obsession”, and a title warns us that none of the gaiety around her dispels her focus on the past—on her lost lover.

Here is Jaques Catelain, again—now in the guise of a boatrace winner, of a youth clad in black mackintosh and driver’s cap and goggles. Natacha, too, sees him. And he sees her—magnificently framed within the window frame, dark clouds seemingly looming all around her. (It’s an extraordinary image, the best shot in the film.) Now the race winner bustles in with a crowd of admirers, round and round through the revolving door of the hotel entrance. Meanwhile, they gaze at each other, these two strangers who seem to share something in this gazing.

Natacha flees this “dream”, but the camera follows her (and so too does Jaques Catelain), speeding along in her car, along the coast, to an Orthodox church, a kind of miniature of something from St Petersburg. Inside, she prays, and the dark face of the icon becomes the superimposed face of Dimitriev—or that of the stranger. And the stranger is here. (Emmy Lynn does wonders with her fur collar, clutching it, covering and uncovering her face.) He picks up her fallen glove, returns it to her, catches her as she swoons.

At home, with Natacha asleep, Catelain becomes a lounge lizard—“It’s a stratagem: bring the cocktails!” he whispers to his servant. In a delightfully appalling interior (fake brick patterns on the walls, on the columns; drapes that obscure the rest of the set; absurd exotic plants) he makes his move. But she goes outside, flees him, perhaps having entranced him a little.

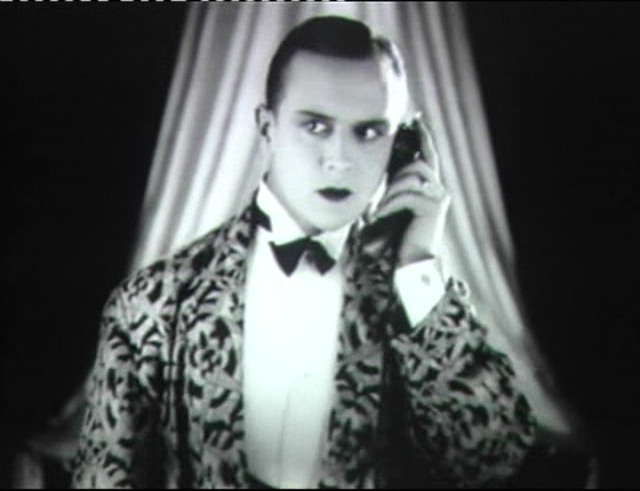

Now she learns his name: Henri de Cassel, engraved on a brass plate at the entrance to the mansion. At home, she looks up his phone number, gazes at Dimitriev’s pocket portrait. Meanwhile, Henri—wearing a staggeringly garish smoking jacket—does the crossword with his mother. He is bored, restless, until Natacha calls and makes a rendezvous with him—or rather, with the man she wants him to be, with Dimitriev.

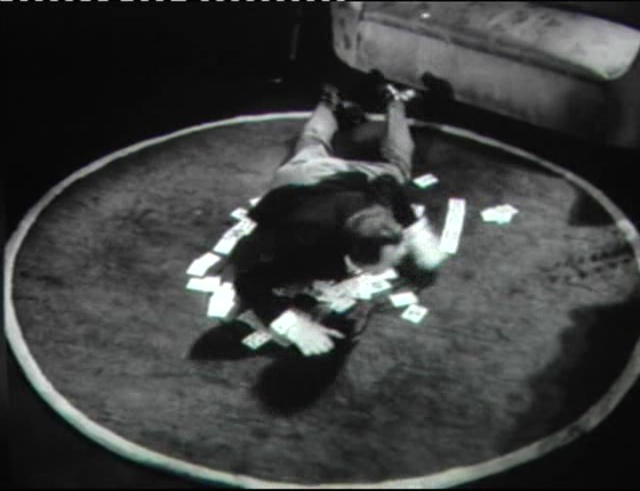

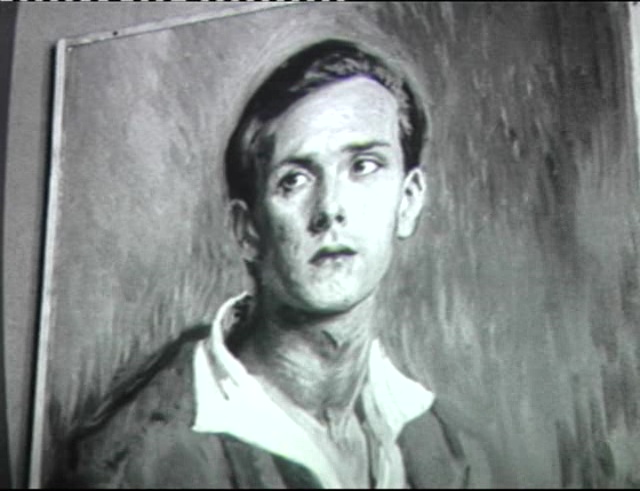

Spied on by Petrov, she leaves the house. Chez Henri, the master of the house is playing an exceedingly elaborate game of patience—or is it fortune telling? He prances around the circle he has made upon the floor, sits, mourns, leaps, runs everywhere when he hears the doorbell. Master and servant, in on the game, rush around—it’s wonderfully silly, and a little sinister, too. Music by Borodin and Balakirev are swiftly put on the piano. A score is opened with a “nuptial march” on display. Automatic doors are opened. Catelain makes a marvellous cad. (He’s more attractive, less artificial, on the wall, in a painting.) For him, Natacha is “ma belle Inconnue”. She responds with a traditional Russian saying, that to attempt to seize love is to see it fly away.

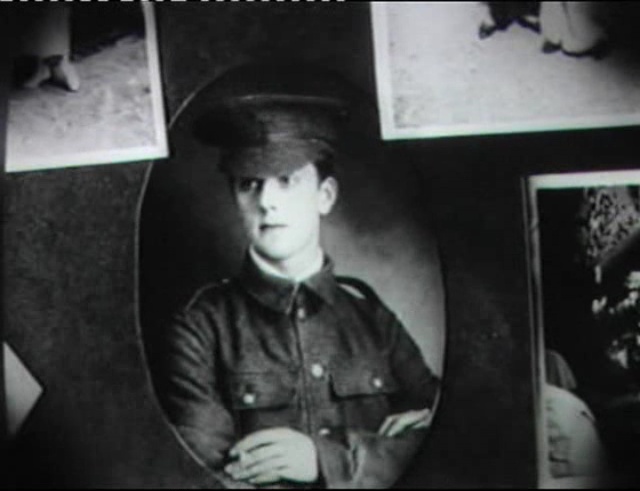

The scene proceeds. He seizes a chance to kiss her hand. She recalls the real past, a real kiss from Dimitriev. He looks sheepish, guilty, confused by her sultry glamour. (The dark dress, the dark hat, the dark veil—and dark eyes, and dark lips.) She sees a photo of him in uniform and it makes him giggle, giggle until she moves in for a kiss—but the telephone rings. She goes to the piano, plays the wedding march. He approaches. L’Herbier gives him a close-up that is threatening, sinister—the bars of a backlit screen behind him, then his face blurring, her face blurring. The past bleeds (dissolves) into the present. Her memories take over. A distant kiss replaces the real scene, the real Henri moving closer. His arms are around her, he grapples with her. Their kiss—is it willing?—shown reflected on the black sheen of the piano lid. It’s marvellously sinister, as is the dissolve to—later. She is leaning back. Again, how willingly has she submitted? He demands to know more about her, grabs her again as she goes to leave. “Try to tread the truth in my eyes. And if you see it, stay silent.” With this, she leaves.

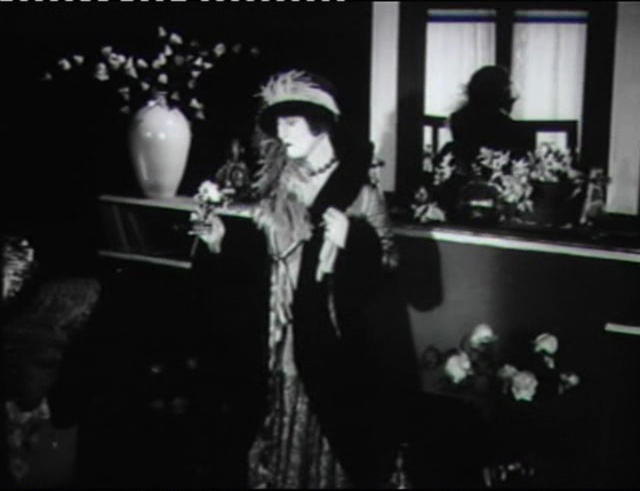

A titled angle. The footsteps of—who? The camera tracking to a door. Natacha followed, found—by her husband. Lynn looks at her fingernails, looks at her watch—it would be comic (it is, a little), if it weren’t for the seriousness of her husband’s questions. “I’m seeking someone that I’ve lost, and wish to find again…” In response, her husband pulls out a gun. He turns it on her, points it in her face. Who has she been seeing? No answer. Natacha laughs, leaves, and her laugh fades. (If she reminds me so much of Marthe in Gance’s Mater Dolorosa [1917], it’s because her fashion—feathers, fur collars, veils, broad-brimmed hats—and acting style—the occasional bulge of the eye, the way she turns, flattens herself against the wall, pauses at doorways—seem hardly to have changed since 1917.)

Chez Henri, a friend, Charançon (Gaston Jacquet), teases him about his disappearing from the social scene. A woman no doubt, but who? The friend conjures exotic possibilities, only for the woman herself to turn up. More comic running about by Catelain, this time with his friend. And when Natacha arrives, they both see Petrov on the street outside, following her.

Henri confronts her. The Shot-reverse-shots, close-ups as each looks into—through—the camera at each other. “You are always obliged to leave, to go SOMEWHERE where SOMEONE awaits you… WHERE?… WHO?…” It’s not clear who says this line: the title has inverted commas, denoting speech, but neither of the close-ups show the protagonists talking. Natacha looks afraid, resigned, shakes her head. He looks angry, then weak, then submits to her touch, like a child seeking his mother. (Emmy Lynn is eight years older than Catelain, but her old-fashioned clothes makes her seem older than she is—just as his babyish face makes him seem younger.) She leaves the room, and Henri seizes the chance to go through her bag. Henri finds a card with her name, her address, and a photograph of Dimitriev. She leaves, but he confronts her: “It’s not me you love. It’s another, ANOTHER whom you love through me.” She says he’s now made it impossible for her to see him again. Clutching the image of his doppelganger, Henri broods.

Now he goes to find his friend, whom he surprises in bed. It’s an extraordinary bed, the friend lying under a furry, feminine expanse of duvet. After being goaded into action, Charançon phones a contact and gets Henri invited to a reception at which the General and Natacha will appear.

It’s another expansive Mallet-Stevens creation: a geometric layout, a jazz band on a stage, cubist sliding doors, cubist signage, angular, deeply uncomfortable-looking furniture. Henri finds Natacha, who wields a giant feather fan in defence. (See too her Russian-dome shaped headpiece, glittering with jewels. She looks extraordinary, remote, glamorous, from another age.) Henri speaks, and L’Herbier intercuts their exchange with the violin solo of the band—it’s as if emotion is being played at, manufactured, summoned as a means to an end.

The lover and husband see one another. The General is shocked. (An exchange of close-ups, of reactions—it’s the closest the camera has been to them yet.) The General questions Charançon about Henri. Again, the glances are intercut with music—and just as a confrontation seems to brew, there is a drumroll. Now a contortionist swings from a trapeze rope in the centre of the space. It’s a bizarre interruption (like a reserve act from the central sets of L’Inhumaine or L’Argent).

But now Petrov sees Henri and also calls our Dimitriev’s name. The machinations swirl around, as more drink is poured. A younger, lither woman than Natacha is flirting with Henri, and the cutting between glances grows more complex. But the brutish nature of the husband becomes simpler, clearer: he downs yet more vodka cocktails, makes his wife dance with Henri. Quick cutting between the dancers, the band, and the couple—whom the General now threatens with a large knife. But it’s swiftly quelled, laughed off. Henri questions Natacha, discovers that the husband killed Dimitriev, but demands her love for him and not “the other”.

Natacha, soon to be forced away from Paris by her husband, goes to see Henri’s mother, to warn her of the General’s threats. Henri eavesdrops, wearing yet another eye-popping piece of home wear, a sort of cubist bath robe. (How strange he dresses like this only around his mother.)

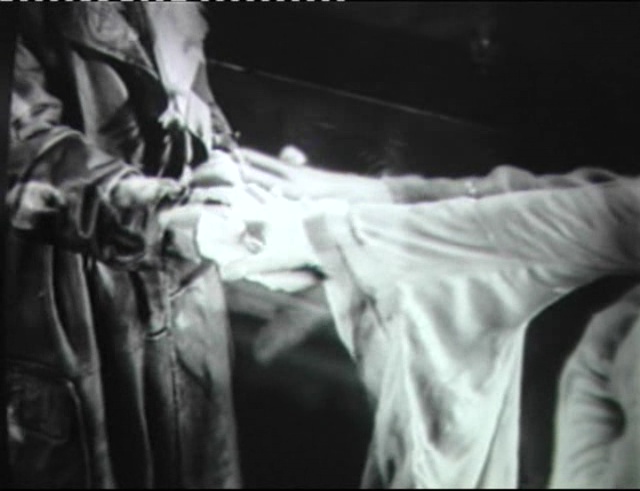

The couple go to Provence (a brief, glorious glimpse of the outside world—exterior shots of silhouetted hilltop towns). The General is visibly ageing. He waves a gun around, half inviting Death to confront him. (She wears another long-sleeved dress: she looks like a glamorous medieval princess.) The wind rises. Dogs bark. Petrov is ordered to release them. He goes through the cavernous villa, sets them loose. Henri is outside. The wind blows through the doors. The General shoots into the heaving wilderness outside. L’Herbier cuts back and forth between exteriors, interiors, faces, places. A shot is fired. A dog falls dead. Henri’s journey to the interior seems to last forever. Long enough for the General to try and force himself on his wife. He’s just revealing her flesh when Henri appears at the threshold. He pulls a gun. For once, he looks serious—convincing. He’s come for Natacha (who is busy emptying the General’s revolver). The General wants to duel, and the men pace out the distance inside. The General looks apoplectic, so much so that he drops dead of rage and age before he can fire a shot in anger. Natacha has been clutching desperately at Henri, the cutting dragging out his bizarre self-induced death. Now the lovers are together, but what is their future? Henri puts on his coat, holds out a hand. She puts out hers, and again the past dissolves over the present—as Dimitriev’s hand also reaches out to her. FIN.

I was urged to rewatch Le Vertige by David Melville Wingrove, for whom it is one of L’Herbier’s outright masterpieces. I see plenty to admire in the film, but I’m afraid it just didn’t do it for me as a whole. The film is nearly two-and-a-quarter hours long, and I wanted it to be condensed into ninety minutes. Both the opening half hour and the closing half hour feel overextended. Neither the melodrama of the Revolution nor of the violent denouement engaged me. But the middle section did have plenty of interest, both visual and thematic. There are lots of interest ideas bubbling away. Natacha’s obsession blinds her to the (initially, at least) selfish motives of Henri in seducing her, and L’Herbier delights in making Henri at first appear both smarmy and faintly ludicrous—anything but the hero that Dimitriev was. (Henri even shows Natacha a photo of him in military uniform, seeming to chuckle afterwards—as though he couldn’t take this part of his life seriously.) And Henri has a strange relationship with the two women in his life: his mother and Natacha. When Natacha first sees him from the hotel, immediately outside is his mother. And later in the film, she goes to Henri’s mother to warn her about the danger to her son—while Henri himself runs away from the two women. I’m not altogether clear of the implications of Henri’s relationship with his mother, or even where his mother is supposed to be living. (A title says they return to Paris together, but that’s all the information we’re given.) What could have been developed into another layer of emotional complication ends up being sidelined. The theme is better developed in L’Inhumaine, where Catelain again plays the boyish figure loved by an older woman. (Emmy Lynn was eight years older than Catelain, and in L’Inhumaine Georgette Leblanc is nearly thirty years older—ten years older than Claire Prélia, who plays Catelain’s mother in Le Vertige.)

This brings me to the two leads in Le Vertige. Jacque Catelain himself often underwhelms me. He can be as good as the film he’s in, but never more so—for me, he’s not a real star and I remain baffled by his appeal. He looks good as a still image, as a poster, even as a painting—but set him to move on camera, ask him to emote, demand he convince us of a life with depth and feeling and truth, and too often he looks totally inadequate. That said, he’s more suited to his character in Le Vertige: a superficial playboy, without great depth. He also gets to do some comic scenes (being bored by his mother, scurrying about with his servant or friend) and plenty of sinister ones. He’s rather good at being a kind of modernist lounge lizard, pouncing on an older, vulnerable woman. The prolonged scene of him and Natacha in his apartment is perhaps the strongest and most interesting in the film. But the trouble is his character is supposed to develop actual feelings for Natacha, and I’m never quite convinced of this on screen. (But again, perhaps this plays into the film’s own ambiguity about the character: at what point are we meant to genuinely trust Henri, believe him?)

Emmy Lynn is altogether more engaging. I’d only seen her in two earlier films, both directed by Gance: Mater Dolorosa (1917) and La Dixième symphonie (1918). In both cases, she plays similar roles of women suffering with private torments. Her performances in all three films are remarkably similar (so too is her wardrobe, though L’Herbier gives her more hats to play with). She does a lot of business with her fur collars, with her fans; she finds doorways and walls to lean against in anguish; she turns her head and closes her eyes, in grief, in suppressed desire. She’s very pleasing to watch and even if she is, in her own way, as mannered a performer as Catelain, hers are much more convincing manners.

Elsewhere, the character of Petrov (Andrews Engelmann, a German actor actually raised in Russia) offers nothing much in the way of subtlety. And as the General, this is one of Roger Karl’s least impressive performances. I’m used to him being stern, reserved, brooding, threatening (in La Femme de nulle part [1921], L’Homme du large, or Maldone [1928]). Here he’s given a slightly silly moustache and he gradually retreats into a hammy form of villainy. Had he been more subtle, I would have felt more for Natacha.

So where does this leave me? I wrote last time that L’Argent is both magnificent and heavy going, but it offers rather more for me than Le Vertige. I respect and admire L’Herbier a great deal, but I’m still left a little cool by his films. As much as I like and enjoy L’Homme du large (1920), El Dorado (1921), my appreciation of his subsequent, longer silent features—Feu Matthias Pascal, L’Inhumaine, L’Argent—tends to flirt with boredom. Though often visually spectacular, none of these films has ever truly moved me. But nevertheless, I persevere, partly out of the hope that one day I will be surprised and genuinely overcome with emotion at something he made. It’s why I have spent so much time picking my way through the film, in the hope that longer reflection might encourage greater appreciation.

Has it? In all honesty, one image in Le Vertige did grab me, emotionally. For me, the best shot in the film is the image of Natacha looking through the huge window to see Henri for the first time. Showing her entrapped, with the dark clouds naturally superimposed by the glass, the shot is so beautifully potent, so full of feeling and meaning. The trouble is, nowhere else in the film did I feel this same sensation. I saw evidence that I was being cued to feel something, but the feeling never came. The image of Natacha behind glass reminds me that I tend to prefer films with a little more fresh air blowing through them. Perhaps it’s because I’m from the countryside that I long to see a director use real locations and exteriors to good effect, and in Le Vertige we get only superficial glances out the window, a handful of establishing shots before L’Herbier swiftly moves inside to show us his interiors. Sadly, fussy modernist design—something in which L’Herbier specializes—holds my interest for only so long.

But it’s this modernist milieu that, understandably, keeps many of his films in the canon. Le Vertige was shown at Pordenone this year as part of a theme devoted to designer Sonia Delaunay. Her work on Le Vertige involved designing the costumes and soft furnishing (seat covers, curtains etc), while Pierre Chareau contributed the furniture, Jean Lurçat the paintings and carpets, Robert Delaunay a painting of the Eiffel Tower (in Henri’s apartment). Contemporary reviewers praised L’Herbier for filling his commercial film with such modernist décor. I concur that it looks great, but it still leaves me cold. It’s impeccable design, but it all feels like an advert for another project—as though the characters live inside sterile modernist showrooms. For much the same reason, I become weary every time I sit through L’Inhumaine, and parts of Le Vertige feels like cast-off scenes from L’Inhumaine. (More generally, films about people feeling alienated in well-appointed rooms have little interest for me. This rules out great swathes of European art cinema of the late 1950s and 1960s.) Again, it comes down to feeling. As much as I loved certain scenes, the film just doesn’t make me feel for its characters. Nevertheless, Le Vertige was a worthwhile watch, and I’d be curious to see what a full restoration with a good score would do for it—and for me.

Paul Cuff