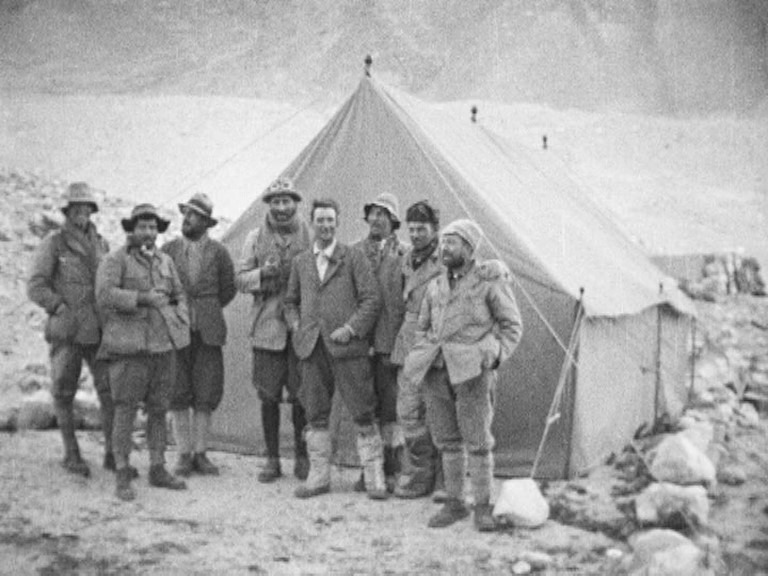

John Noel had an extraordinary early life. Born in southwest England, educated in Switzerland, and posted with the British army to India, he fell in love with mountains at an early age. When his unit was stationed near the Himalayas in 1913, he travelled in disguise into Tibet to get a glimpse of Mount Everest. He served with the BEF in 1914, being taken prisoner at the battle of Le Cateau before escaping his captors and returning to active service. After the war, he became involved with the Royal Geographical Society and Alpine Club, joining the 1922 expedition to Everest as official photographer. He experimented with new kinds of telescopic lens to photograph and film at long distance in the mountains. The result was the short film Climbing Mount Everest (1922), as well as a desire to do better next time. In 1924, he helped fund the next expedition to Everest, led by General Charles G. Bruce. This time, Noel would record enough footage for a feature film. If the expedition was a success, he hoped to film the team’s actual ascent to the summit. And if the expedition failed…?

This film has been sat on my shelf for a long time. Having written about South: Sir Ernest Shackleton’s Glorious Epic of the Antarctic (1919), and having seen The Great White Silence (1924), I knew I would get to it eventually. Thanks to the very cold weather we had in January, I was finally inspired to watch it. The first thing to say about The Epic of Everest is that it is astonishingly beautiful to look at. The 2013 restoration by the BFI presents the remarkable footage in as good a quality as could be hoped.

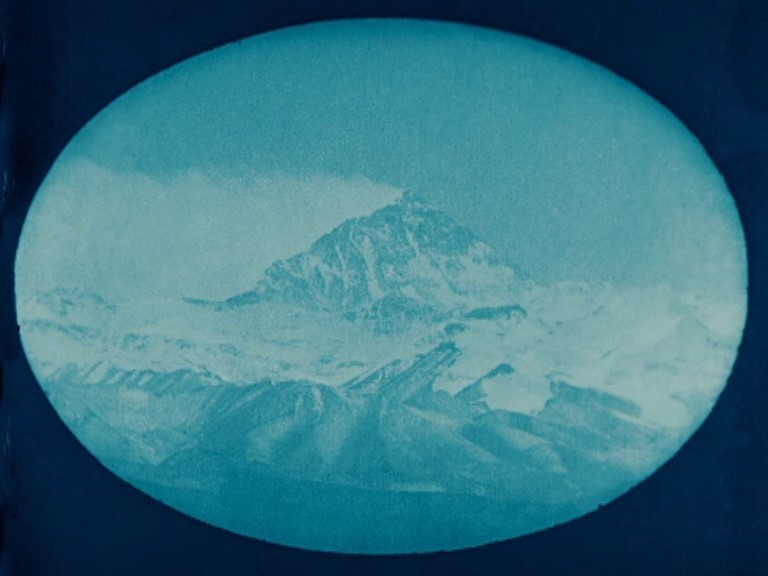

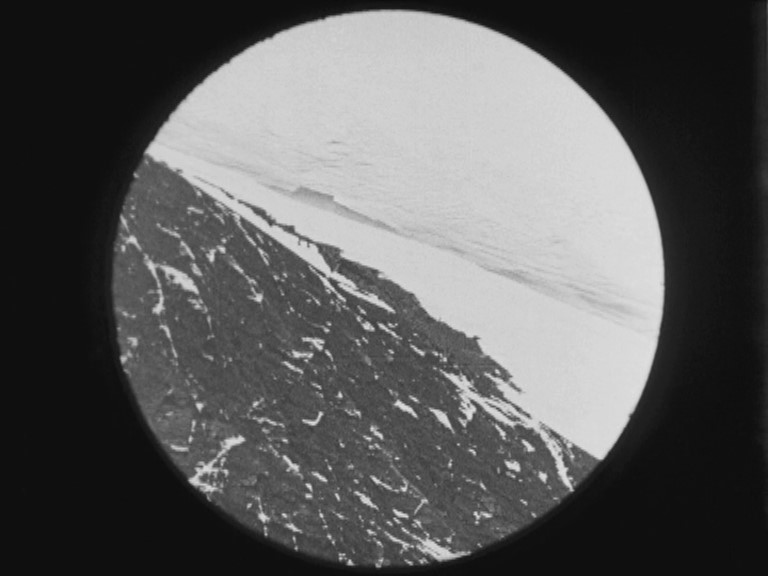

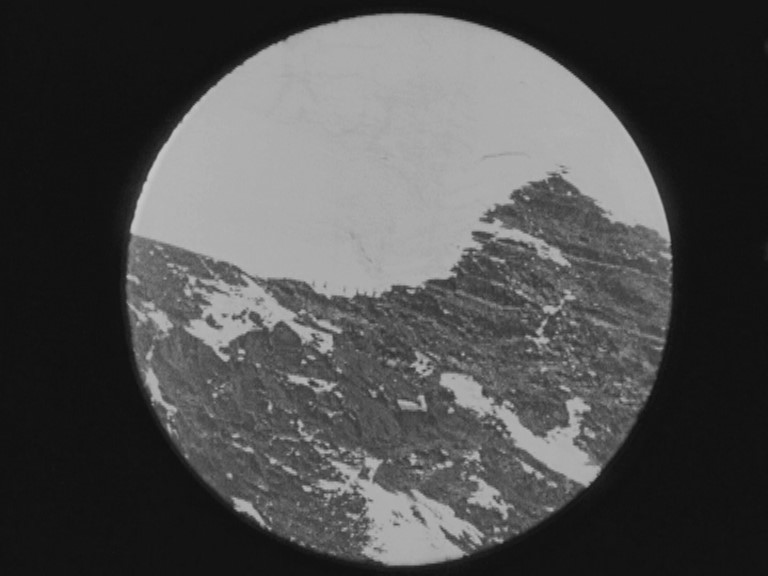

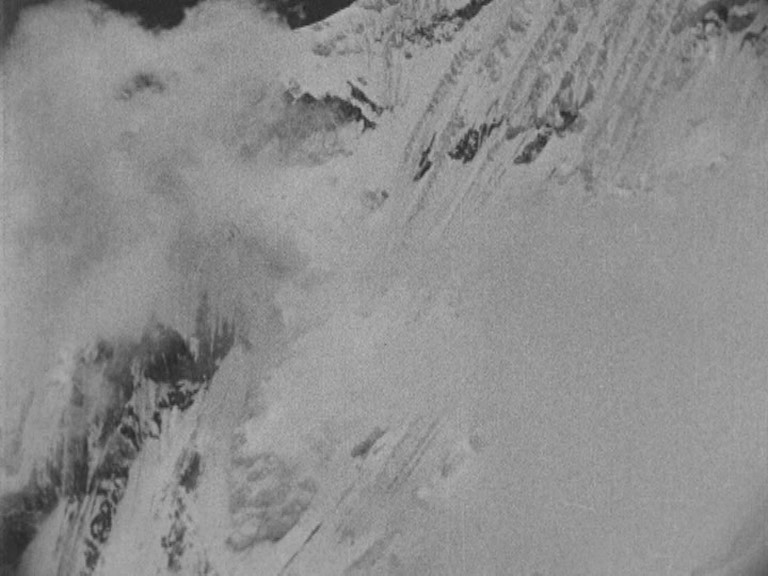

The grain of the image lets you feels the rocks and ice and clouds, as well as the texture of the clothing and animal hides. The scenes tinted blue, pink, or give a dramatic, otherworldly quality to the film—but the landscapes are otherworldly enough in monochrome. Indeed, the whites and blacks seem almost destined to be used for such mountainous terrain. Noel plays with space and time, so that the mountains attain a magical sense of life: we see light and shade rushing across gleaming slopes, or darkness creeping up sheer cliffs of ice. Clouds pass at preternatural speed over the ridges and summits, or obscure whole swathes of the world. The silhouette of Everest itself becomes a constant visual anchor: it’s as though it is the one constant presence in a landscape at the mercy of elements. And it’s a kind of visual motif that embodies the obsession of the expedition that wishes to climb it. That we see the summit so often, without ever being about to reach it, is emblematic of the entire narrative.

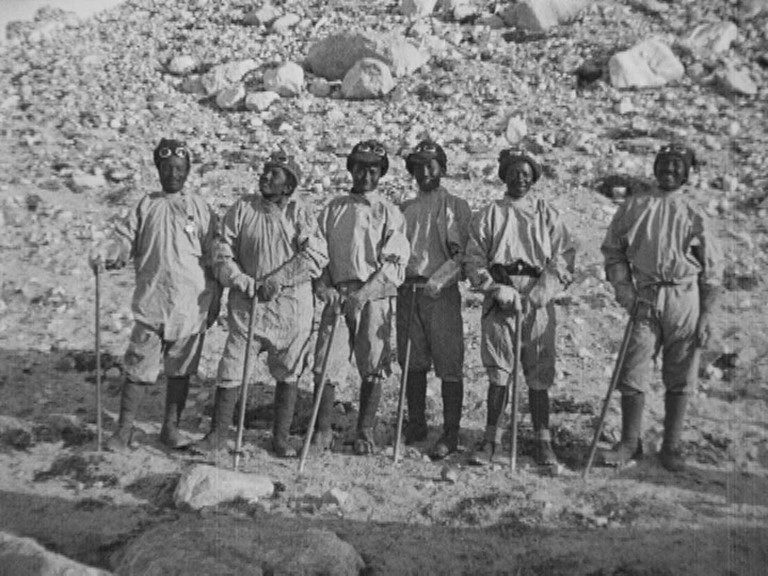

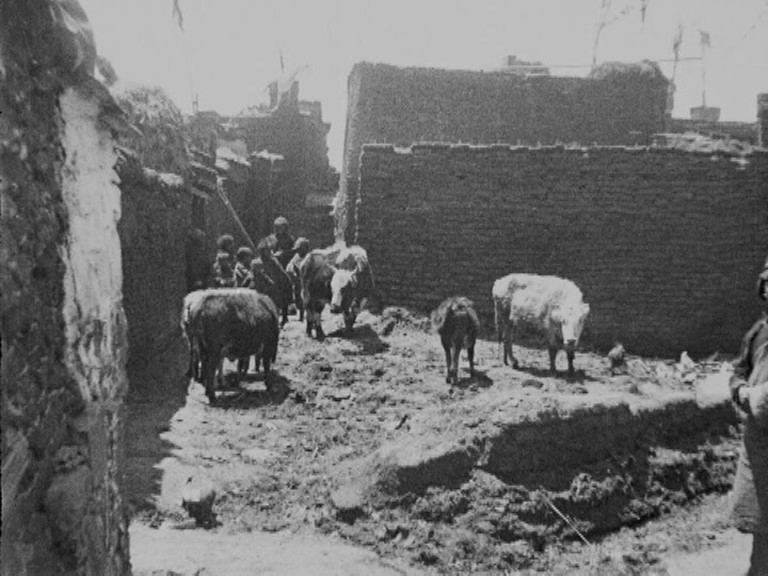

These remarks aside, I was a little worried by the opening section of the film. There are a lot of titles, interspersed with one or two shots of landscapes. The landscapes looked beautiful, but I was concerned how much work the titles would have to do to shape the footage into a narrative. Happily, the film settles down after a few minutes and the footage dominates the text. The progress of the expedition is visually clear, helped by some marvellous compositions. The landscapes are also so vast that the literal progress of the lines of men, women, and animals is naturally choreographed. From the large crowds of porters and animals, we then see smaller teams of men and animals, and finally just men. And all the while, the terrain becomes steeper, whiter, harsher.

Indeed, it is the sense of scale that The Epic of Everest most brilliantly conveys. Noel composes the figures in this landscape carefully, so that we always get a sense of how small they are compared to the slopes. What’s more, the extraordinary telescopic lens he uses enable us to see across huge swathes of land to pick out the tiny dots of figures on distant slopes. You really do get the sense of the vastness of this terrain, and the vulnerability of the climbers. If Noel offers us a few glimpses of the faces of the main team and of the local porters, we never linger on any of them for that long. In fact, the only sustained close-ups we get of anyone in the expedition are the two still images of Mallory and Irvine near the end of the film. If this denies us a direct emotional involvement with the figures, it also concentrates all our attention on the reality of the world they inhabit. The drama is often played out at great distance, so the titles must do a lot of narrating for us (together with lots of undercranking to speed up the slowness of their traversal of the snow).

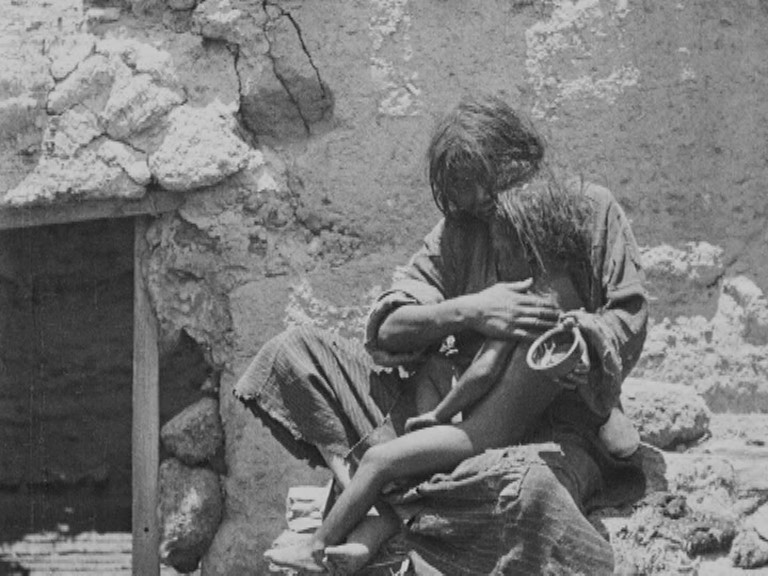

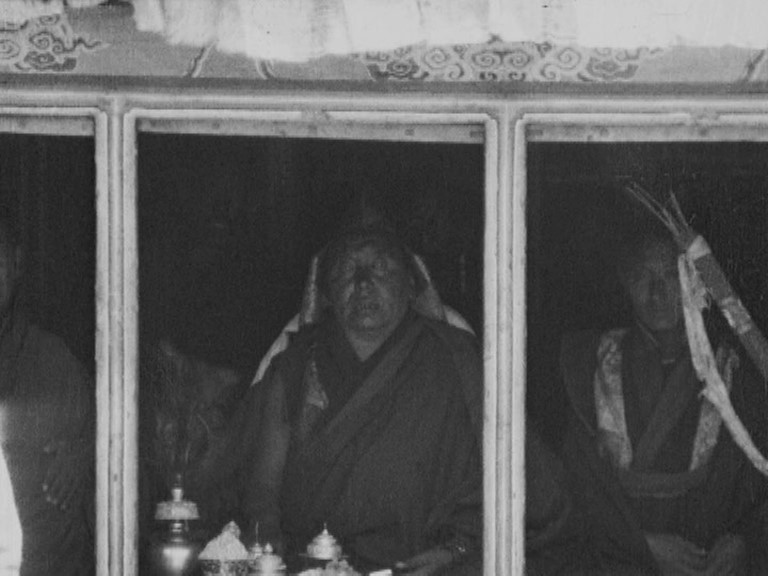

The film’s attitude to the nature and purpose of the expedition is also interesting. As far as the presence and culture of the local Tibetans is concerned, the perspective of The Epic of Everest is a little mixed. We are introduced to one village by being told how filthy and smelly it is, and the tone of other titles is rather patronising. (It is unclear if the film expects or encourages its contemporary Western audiences to laugh.) But I was surprised by how much respect the Tibetans are given: they are thanked for their welcome, company, and help; their temples and religious customs are given nodding respect—to the extent of being given some credence. For we are told that the Lama visited by the climbers told them that their expedition would fail, and the film acknowledges that he was right—even that it was a kind of destiny foreknown.

Which brings us to the ending. Narratively, the film is far stronger than Herbert Ponting’s The Great White Silence. Since the filmmakers could not accompany Scott and his team to the South Pole in 1912, the story of their fate is told via substitute footage and an animated map. Conversely, though filmmaker Franky Hurley was present throughout the gruelling events depicted in South in 1914-16, he was unable to film any of the climactic journey and rescue. That film ends with footage of the location recorded long after, with a lot of wildlife thrown in for good measure. Both are unsatisfactory ways to conclude fascinating narratives. But for The Epic of Everest, Noel was present and filming throughout the climactic events. And there is a powerful irony in the fact that the film’s boasts of telescopic lenses proved powerless against the weather to record the final stretch of Mallory and Irvine’s attempt to reach the summit. Like Noel, we can only sit at a great distance and observe the slow and often obscure events unfold. One moment, the climbers are tiny dots, the next they are lost in cloud. We wait. Hours pass. Other figures appear, messages are relayed with painful slowness. Mallory and Irvine have disappeared, and the film cannot solve the mystery or offer us any alternate means of representing what happened.

In dealing with the failure of the expedition, and the death of two of its members, the film becomes surprisingly reflective. If Mallory and Irvine died, we are asked, isn’t resting forever in this astonishing landscape an idyllic kind of afterlife? Further, the text of the titles wonders if the expedition was fated to fail, and whether some spiritual aspect of the mountain—and, implicitly, of Tibetan culture—prevented them from reaching their goal. It returns to the native idea of the mountain as a goddess that protects herself from intruders—especially (I think it is implied) from those outside of Tibetan culture. Whether the filmmaker is being sincere, or is just finding a convenient way of ending the film on a dramatically satisfying fashion, is up for debate. But I think the ending does succeed narratively and emotionally: the last images, tinted a burnished red, of the mountain drawing the darkness up over its flanks and summit is an exceptionally beautiful way of making a sense of irresolution a fitting conclusion.

The BFI restoration comes with a choice of two scores. The first is by Simon Fisher Turner. I say “first” because the cover of the Blu-ray credits this as “a film by Captain John Noel with music by Simon Fisher Turner”. (Not quite in the same league as the BFI release which Amazon sells under the title “Michael Nyman’s Man With A Movie Camera”, which really takes the biscuit.) Described in the liner notes of this edition as “an epic of contemporary music-making”, it boasts an array of sampled sounds—from the original 1924 recordings of Tibetan vocalists recorded by the expedition to various kinds of “silence”, yak bells etc. The music that is not sampled or recorded on location is rather more generic. Washes and warblings of sound, dashes of synthesized brass, tinklings and scratchings, breathy acoustic sighs… This mood music engages only in the very broadest way with the rhythm of the film, or the rhythm of watching it.

The liner notes contain a very brief essay by Fisher Turner. “Where do I begin?” he asks. “On the internet.” He freely acknowledges his role as acoustic “thief”, while also emphasizing the improvisatory way he compiles pre-existing and original sections of the soundtrack. It’s difficult to reconcile the claim of this being an “epic of contemporary music-making” with Fisher Turner’s own account of downloading apps and stealing audio from online videos. Bits of his essay read like parody: “Ideas come and go. Puzzle making. Noise collecting. Soft electricity. Sound climbing. Notimemusic. Snowblind snarls. I meet Ruby and Madan, and play music on the sofa, and eat Nepalese lunch with blue skies and new friends.” Epic indeed. At least Fisher Turner’s soundtrack for The Epic of Everest is preferable to his score for The Great White Silence, which I found entirely unenjoyable—and sometimes downright stupid. (At one point, the soundscape lapses into silence. Fisher Turner himself then appears in audio form, telling us that the silence we are listening to was recorded at Scott’s cabin in Antarctica. Having to appear on your soundtrack to explain the soundtrack is absurd enough, but Fisher Turner chooses to speak at the very moment when there is a lengthy intertitle on screen. Trying to read one voice and listen to another is difficult, and it struck me as the very acme of aesthetic imposition to literally talk over the film while the film itself was “talking”.)

I wonder how much money was spent commissioning and recording the Fisher Turner soundtrack, and how much was spent on its alternative: the reconstruction of the 1924 orchestral score? The relative market standing of the two soundtracks is clear enough from the way the modern one is prioritized in publicity and on packaging. The liner notes also promise that Fisher Turner’s score is available on “deluxe limited-edition vinyl” and CD. But not, of course, the 1924 score. And you must go past two essays on the modern soundtrack before you reach Julie Brown’s excellent essay on the 1924 score, which is the last one included in the booklet.

So, what of the 1924 score? It was compiled for the film’s screening at the New Scala Theatre in London by the renowned conductor Eugene Goossens (Senior) and composer Frederick Laurence. It consists mainly of music from the existing repertory, together with some specially composed pieces for a few sequences. Much of the music is familiar: there is a lot of Borodin, some Mussorgsky, Korngold, Lalo, Prokofiev, and Smetana. Then there are the more obscure pieces by lesser-known composers: Joachim Raff, Félix Fourdrain, Hermann Goetz, Henri Rabaud. Of the latter, I knew the music of Fourdrain and Rabaud only through other silent film scores. Some of Fourdrain’s music was used in the score compiled by Paul Fosse and Arthur Honegger for Abel Gance’s La Roue (1922), while Rabaud composed the scores for Raymond Bernard’s historical epics La Miracle des loups (1924) and Le Joueur d’échecs (1927).

The music has much to do in keeping a sense of pace and involvement with The Epic of Everest, as the succession of landscapes and titles can sometimes become monotonous—or at least mono-rhythmic. Having solid symphonic works, neatly arranged, provides another temporal dimension to our viewing experience.

There are also some oddities. One sequence is introduced with the title: “Into the heart of the pure blue ice, rare, cold, beautiful, lonely—Into a Fairyland of Ice.” The music cued at this point is the Moldau movement from Smetana’s Má vlast (1872-79). But while Smetana’s music famously captures water in motion, the images on screen are of water arrested: a sonic depiction of racing rivers accompanies the sight of frozen drifts. Elsewhere, there are slightly awkward accompaniments around scenes of Tibetan life. Thus, when a mother is scene happily giving her child a “butter bath”, the music is oddly dramatic. But it is hardly more at odds with the scene than Fisher Turner’s mood-music synth wash with odd clicks and scratches.

Besides, there are far more scenes where the 1924 choices work wonderfully—even with music that is familiar from other contexts. Thus, we get Mussorgsky’s “St. John’s Eve on Bald Mountain” (1867) accompanying a sequence of images of wind and snow blasting across Everest and its approaches. (“Should you not mind wind or frost of fifty degrees, you may stand out on the glacier and watch the evening light beams play over the ice world around.”) It’s fabulously evocative, sinister, thrilling music—every bit the equal of Noel’s images. The original music by Frederick Laurence that introduces the Kampa-Dzong temple (“Tibetan chant”) is also marvellously simple and evocative (harp chords and, I think, bass notes on the piano). And for the last scenes of the film, where the mood changes to one of brooding reflection and resignation, we get another excellent arrangement. Rabaud’s “Procession nocturne” (1899) soars slowly, ecstatically over the images—before the score switches to the sinister fugue from Foudrain’s prelude to Madame Roland (1913) as darkness encroaches over the mountain.

For the BFI restoration, the music is performed by the Cambridge University Chamber Orchestra, conducted by Andrew Gourlay. I’d not encountered this group before and had an initial concern that budget might restrict either the size of the orchestra or the quality of the performance. I was happily surprised by both aspects: the sound is full and rich, the music well played and decently recorded. The sonic depth and complexity of a symphony orchestra is immeasurably preferable to the kinds of four- or five-person ensembles advertised as “orchestras” on some silent film releases. The Epic of Everest benefits enormously from its original score, and I wish more releases would take the trouble (or be given the budget) to provide music of this scale and quality.

Paul Cuff